Baumol & Blinder MACROECONOMICS (11th ed)

.pdf

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 17 |

International Trade and Comparative Advantage |

347 |

A similar story applies to Japan. If the Japanese produce only television sets—point J in Figure 2(a)—they can acquire a computer from the United States for every two TVs they give up as they move along the brick-colored line JP (whose slope is 2). This result is better than they can achieve on their own, because a sacrifice of two TVs in Japan yields only one-half of a computer. Hence, world trade enlarges Japan’s consumption possibilities from JN to JP.

Figure 2 shows graphically that gains from trade arise to the extent that world prices (2:1 in our example) differ from domestic opportunity costs (4:1 and 1:1 in our example). How the two countries share the gains from trade depends on the exact prices that emerge from world trade. As explained in the appendix, that in turn depends on relative supplies and demands in the two countries.

Must Specialization be Complete?

In our simple numerical and graphical examples, international specialization is always complete—for example, the United States makes all the computers and Japan makes all the TV sets. But if you look at the real world, you will find mostly incomplete specialization. For example, the United States is the world’s biggest importer of both petroleum and automobiles. But we also manufacture lots of cars and drill for lots of oil at home. In fact, we even export some cars. This stark discrepancy between theory and fact might worry you. Is something wrong with the theory of comparative advantage?

Actually, there are many reasons why specialization is typically incomplete, despite the validity of the principle of comparative advantage. Two of them are simple enough to merit mentioning right here.

First, some countries are just too small to provide the world’s entire output, even when they have a strong comparative advantage in the good in question. In our numerical example, Japan just might not have enough labor and other resources to produce the entire world output of televisions. If so, some TV sets would have to be produced in the United States.

Second, you may have noticed that in this chapter we have drawn all the production possibilities frontiers (PPFs) as straight lines, whereas they were always curved in previous chapters. The reason is purely pedagogical: We wanted to create simple examples that lend themselves to numerical solutions. It is undoubtedly more realistic to assume that PPFs are curved. But that sort of technology leads to incomplete specialization, which is a complication best left to more advanced courses.

|

ISSUE RESOLVED: |

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE EXPOSES THE |

|

||

|

|

“CHEAP FOREIGN LABOR” FALLACY |

The principle of comparative advantage takes us a long way toward understanding the fallacy in the “cheap foreign labor” argument described at the beginning of this chapter. Given the assumed productive efficiency of American labor, and the inefficiency of Japanese labor, we would expect wages to be much higher in the United States.

In these circumstances, one might expect American workers to be apprehensive about an agreement to permit open trade between the two countries: “How can we hope to meet the unfair competition of those underpaid Japanese workers?” Japanese laborers might also be concerned: “How can we hope to meet the competition of those Americans, who are so efficient in producing everything?”

The principle of comparative advantage shows us that both fears are unjustified. As we have just seen, when trade opens up between Japan and the United States, workers in both countries will be able to earn higher real wages than before because of the increased productivity that comes through specialization.

As Figure 2 shows, once trade opens up, Japanese workers should be able to acquire more TVs and more computers than they did before. As a consequence, their living

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

348 |

PART 4 |

The United States in the World Economy |

standards should rise, even though they have been left vulnerable to competition from the super-efficient Americans. Workers in the United States should also end up with more TVs and more computers. So their living standards should also rise, even though they have been exposed to competition from cheap Japanese labor.

These higher standards of living, of course, reflect the higher real wages earned because workers become more productive in both countries. The lesson to be learned here is elementary:

Nothing helps raise living standards more than a greater abundance of goods.

TARIFFS, QUOTAS, AND OTHER INTERFERENCES WITH TRADE

Mercantilism is a doctrine that holds that exports are good for a country, whereas imports are harmful.

A tariff is a tax on imports.

A quota specifies the maximum amount of a good that is permitted into the country from abroad per unit of time.

Despite the large mutual gains from international trade, nations often interfere with the free movement of goods and services across national borders. In fact, until the rise of the free-trade movement about 200 years ago (with Adam Smith and David Ricardo as its vanguard), it was taken for granted that one of the essential tasks of government was to impede trade, presumably in the national interest.

Then, as now, many people argued that the proper aim of government policy was to promote exports and discourage imports, for doing so would increase the amount of money foreigners owed the nation. According to this so-called mercantilist view, a nation’s wealth consists of the amount of gold or other monies at its command.

Obviously, governments can pursue such a policy only within certain limits. A country must import vital foodstuffs and critical raw materials that it cannot provide for itself. Moreover, mercantilists ignore a simple piece of arithmetic: It is mathematically impossible for every country to sell more than it buys, because one country’s exports must be some other country’s imports. If everyone competes in this game by cutting imports to the bone, then exports must shrivel up, too. The result is that everyone will be deprived of the mutual gains from trade. Indeed, that is precisely what happens in a trade war.

After the protectionist 1930s, the United States moved away from mercantilist policies designed to impede imports and gradually assumed a leading role in promoting free trade. Over the past 60 years, tariffs and other trade barriers have come down dramatically.

In 1995, the United States led the world to complete the Uruguay Round of tariff reductions and, just before that, the country joined Canada and Mexico in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The latter caused a political firestorm in the United States in 1993 and 1994, with critic (and 1992 presidential candidate) Ross Perot predicting a “giant sucking sound” as American workers lost their jobs to competition from “cheap Mexican labor.” (Does that argument sound familiar?) Most of the world’s trading nations are now engaged in a new multiyear round of trade talks, under guidelines adopted at an important meeting in Doha, Qatar, in 2001. (See “Liberalizing World Trade: The Doha Round.”)

Modern governments use three main devices when seeking to control trade: tariffs, quotas, and export subsidies.

A tariff is simply a tax on imports. An importer of cars, for example, may be charged $2,000 for each auto brought into the country. Such a tax will, of course, make automobiles more expensive and favor domestic models over imports. It will also raise revenue for the government. In fact, tariffs were a major source of tax revenue for the U.S. government during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—and also a major source of political controversy. But the United States is a low-tariff country nowadays, with only a few notable exceptions. However, many other countries rely on heavy tariffs to protect their industries. Indeed, tariff rates of 100 percent or more are not unknown in some countries.

A quota is a legal limit on the amount of a good that may be imported. For example, the government might allow no more than 5 million foreign cars to be imported in a year. In some cases, governments ban the importation of certain goods outright—a quota of zero. The United States now imposes quotas on a smattering of goods, including textiles, meat, and sugar. Most imports, however, are not subject to quotas. By reducing supply,

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 17 |

International Trade and Comparative Advantage |

349 |

quotas naturally raise the prices of the goods subject to quotas. For example, sugar is vastly more expensive in the United States than it is elsewhere in the world.

An export subsidy is a government payment to an exporter. By reducing the exporter’s costs, such subsidies permit exporters to lower their selling prices and compete more effectively in world trade. Overt export subsidies are minor in the United States. But some foreign governments use them extensively to assist their domestic industries—a practice that provokes bitter complaints from American manufacturers about “unfair competition.” For example, years of heavy government subsidies helped the European Airbus consortium take a sizable share of the world commercial aircraft market away from U.S. manufacturers like Boeing and McDonnell-Douglas—a trend that has lately reversed.

An export subsidy is a payment by the government to exporters to permit them to reduce the selling prices of their goods so they can compete more effectively in foreign markets.

Tariffs versus Quotas

Although both tariffs and quotas reduce international trade and increase the prices of domestically produced goods, there are some important differences between these two ways to protect domestic industries.

First, under a quota, profits from the higher price in the importing country usually go into the pockets of the foreign and domestic sellers of the products. Limitations on supply (from abroad) mean (a) that customers in the importing country must pay more for the product and (b) that suppliers, whether foreign or domestic, receive more for every unit they sell. For example, the right to sell sugar in the United States under the tight sugar quota has been extremely valuable for decades. Privileged foreign and domestic firms can make a lot of money from quota rights.

By contrast, when trade is restricted by a tariff instead, some of the “profits” go as tax revenues to the government of the importing country. (Domestic producers still benefit, because they are exempt from the tariff.) In this respect, a tariff is certainly a better proposition than a quota for the country that enacts it.

Another important distinction between the two measures arises from their different implications for productive efficiency. Because a tariff handicaps all foreign suppliers

Liberalizing World Trade: The Doha Round

The time and place were not auspicious: an international gathering in the Persian Gulf just two months after the September 11, 2001 terrorists attacks. Nerves were frayed, security was extremely tight, and memories of a failed trade meeting in Seattle in 1999 lingered on. Yet representatives of more than 140 nations, meeting in Doha, Qatar, in November 2001, managed to agree on the outlines of a new round of comprehensive trade negotiations—one that now appears unlikely to be completed.

The so-called Doha Round focuses on bringing down tariffs, subsidies, and other restrictions on world trade in agriculture, services, and a variety of manufactured goods. It also seeks greater protection for intellectual property rights, while making sure that poor countries have access to modern pharmaceuticals at prices they can afford. Reform of the World Trade Organization’s own rules and procedures is also on the agenda. Perhaps most surprisingly, the United States has even promised to consider changes in its antidumping laws, which are used to keep many foreign goods out of U.S. markets. (Dumping is explained at the end of this chapter.)

Large-scale trade negotiations such as this one, involving more than 100 countries and many different issues, take years to complete. (The last one, the Uruguay Round, took seven years.) And the

Doha Round almost collapsed in 2003 and again in 2006 when negotiating sessions got nowhere. In early 2008, there was not much optimism that the contentious agricultural issues could be resolved, leaving many observers doubting that the Doha Round would ever be completed. But no one knows what the future may bring.

SOURCE: © Patrick Baz/AFP/Getty Images

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

350 |

PART 4 |

The United States in the World Economy |

equally, it awards sales to those firms and nations that can supply the goods most cheaply—presumably because they are more efficient. A quota, by contrast, necessarily awards its import licenses more or less capriciously—perhaps in proportion to past sales or even based on political favoritism. There is no reason to expect the most efficient suppliers will get the import permits. For example, the U.S. sugar quota was for years suspected of being a major source of corruption in the Caribbean.

If a country must inhibit imports, two important reasons support a preference for tariffs over quotas:

1.Some of the revenues resulting from tariffs go to the government of the importing country rather than to foreign and domestic producers.

2.Unlike quotas, tariffs offer special benefits to more efficient exporters.

WHY INHIBIT TRADE?

To state that tariffs provide a better way to inhibit international trade than quotas leaves open a far more basic question: Why limit trade in the first place? It has been estimated that trade restrictions cost American consumers more than $70 billion per year in the form of higher prices. Why should they be asked to pay these higher prices? A number of answers have been given. Let’s examine each in turn.

Gaining a Price Advantage for Domestic Firms

A tariff forces foreign exporters to sell more cheaply by restricting their market access. If the foreign firms do not cut their prices, they will be unable to sell their goods. So, in effect, a tariff amounts to government intervention to rig prices in favor of domestic producers.5

Not bad, you say. However, this technique works only as long as foreigners accept the tariff exploitation passively—which they rarely do. More often, they retaliate by imposing tariffs or quotas of their own on imports from the country that began the tariff game. Such tit-for-tat behavior can easily lead to a trade war in which everyone loses through the resulting reductions in trade. Something like this, in fact, happened to the world economy in the 1930s, and it helped prolong the worldwide depression. Preventing such trade wars is one main reason why nations that belong to the World Trade Organization (WTO) pledge not to raise tariffs.

Tariffs or quotas can benefit particular domestic industries in a country that is able to impose them without fear of retaliation. But when every country uses them, every country is likely to lose in the long run.

Protecting Particular Industries

The second, and probably more frequent, reason why countries restrict trade is to protect particular favored industries from foreign competition. If foreigners can produce steel or shoes more cheaply, domestic businesses and unions in these industries are quick to demand protection. And their governments may be quite willing to grant it.

The “cheap foreign labor” argument is most likely to be invoked in this context. Protective tariffs and quotas are explicitly designed to rescue firms that are too inefficient to compete with foreign exporters in an open world market. But it is precisely this harsh competition that gives consumers the chief benefits of international specialization: better products at lower prices. So protection comes at a cost.

5 For more details on this, see the appendix to this chapter.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 17 |

International Trade and Comparative Advantage |

351 |

Thinking back to our numerical example of comparative advantage, we can well imagine the indignant complaints from Japanese computer makers as the opening of trade with the United States leads to increased imports of American-made computers. At the same time, American TV manufacturers would probably express outrage over the flood of imported TVs from Japan. Yet it is Japanese specialization in televisions and U.S. specialization in computers that enables citizens of both countries to enjoy higher standards of living. If governments interfere with this process, consumers in both countries will lose out.

Industries threatened by foreign competition often argue that some form of protection against imports is needed to prevent job losses. For example, the U.S. steel industry has made exactly this argument time and time again since the 1960s—most recently in 2001, when world steel prices plummeted and imports surged. And the U.S. government has usually delivered some protection in response. But basic macroeco-

nomics teaches us that there are better ways to stimulate employment, such as raising aggregate demand.

A program that limits foreign competition will be more effective at preserving employment in the particular protected industry. But such job gains typically come at a high cost to consumers and to the economy.

Table 4 estimates some of the costs to American consumers of using

jewelr y

tariffs and quotas to save jobs in selected industries. In every case, the costs far exceed the annual wages of the workers in the protected industries—ranging as high as $600,000 per job for the sugar quota.

Nevertheless, complaints over proposals to reduce tariffs or quotas may be justified unless something is done to ease the cost to indi-

vidual workers of switching to the product lines that trade makes profitable.

The argument for free trade between countries cannot be considered airtight if governments do not assist the citizens in each country who are harmed whenever patterns of production change drastically—as would happen, for example, if governments suddenly reduced tariff and quota barriers.

Owners of television factories in the United States and of computer factories in Japan may see large investments suddenly rendered unprofitable. Workers in those industries may see their special skills and training devalued in the marketplace. Displaced workers also pay heavy intangible costs—they may need to move to new locations and/or new industries, uprooting their families, losing old friends and neighbors, and so on. Although the majority of citizens undoubtedly gain from free trade, that is no consolation to those who are its victims.

To mitigate these problems, the U.S. government follows two basic approaches. First, our trade laws offer temporary protection from sudden surges of imports, on the grounds that unexpected changes in trade patterns do not give businesses and workers enough time to adjust.

Second, the government has set up trade adjustment assistance programs to help workers and businesses that lose their jobs or their markets to imports. Firms may be eligible for technical assistance, government loans or loan guarantees, and permission to delay tax payments. Workers may qualify for retraining programs, longer periods of unemployment compensation, and funds to defray moving costs. Each form of assistance is designed to ease the burden on the victims of free trade so that the rest of us can enjoy its considerable benefits.

National Defense and Other Noneconomic Considerations

A third rationale for trade protection is the need to maintain national defense. For example, even if the United States were not the most efficient producer of aircraft, it might still be rational to produce our own military aircraft so that no foreign government could ever cut off supplies of this strategic product.

Cost per Job Saved

$139,000

97,000

415,000

600,000

202,000

102,000

SOURCE: Gary C. Hufbauer and Kimberly Ann Elliott, Measuring the Costs of Protectionism in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics; January 1994), Table 1.3, pp. 12–13.

Trade adjustment assistance provides special unemployment benefits, loans, retraining programs, and other aid to workers and firms that are harmed by foreign competition.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

352 |

PART 4 |

The United States in the World Economy |

How Popular Is Protectionism?

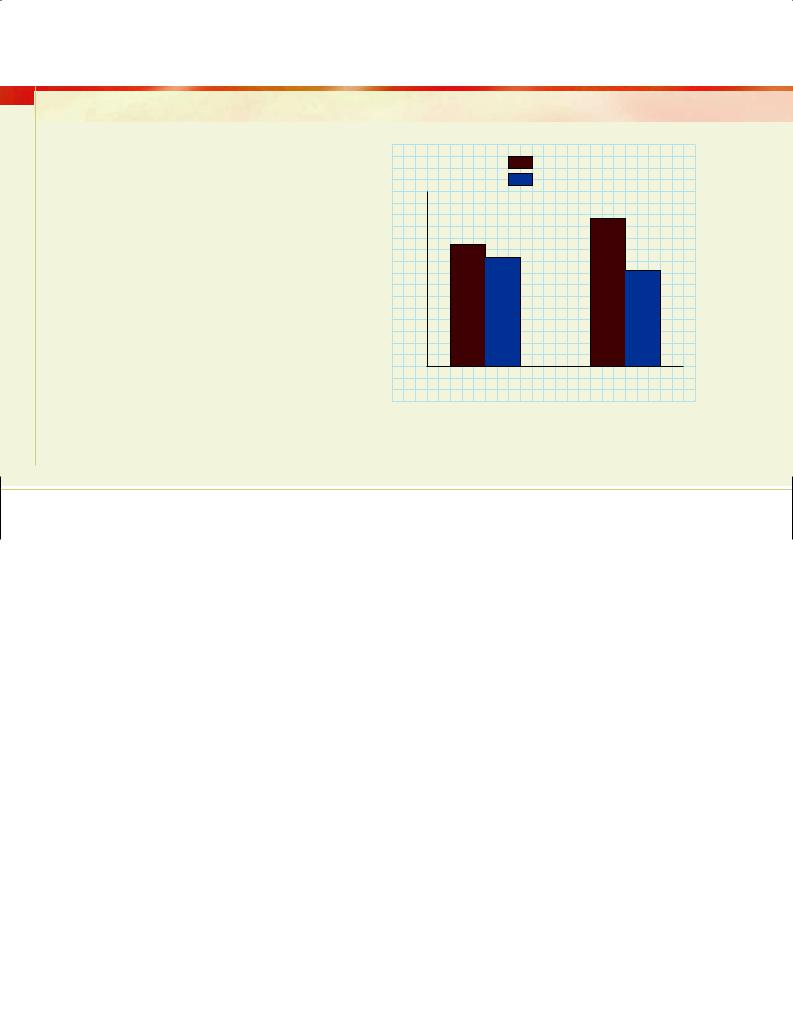

Since World War II, the world has mainly been moving toward freer trade and away from protection. But the people of the world are not convinced that this trend is desirable. In what was probably the most comprehensive polling ever conducted on the subject, a Canadian firm asked almost 13,000 people in 22 countries the following question in 1998: “Which of the following two broad approaches do you think would be the best way to improve the economic and employment situation in this country—protecting our local industries by restricting imports, or removing import restrictions to increase our international trade?” The protectionist response narrowly outnumbered the free-trade response by a 47 percent to 42 percent margin. (The rest were undecided.) Protectionist sentiment was much stronger in the United States, however, where the margin was 56 percent to 37 percent. (See the accompanying graph.)

That was in 1998. In the United States (and elsewhere), there is clear evidence that protectionist sentiment is actually gaining in popularity. For example, a Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll in 1999 found that 39 percent of Americans believed that trade agreements have helped the United States, while 30 percent believed they had hurt. When that same question was asked in 2007, only 28 percent thought trade agreements had helped, while 46 percent thought they had hurt.

Protectionists

Free traders

|

|

56% |

|

47% |

|

Percentage |

42% |

|

|

37% |

|

|

|

|

|

World |

United States |

SOURCES: “How Popular Is Protectionism?” The Economist, January 2, 1999; and Grant Aldonas, Robert Lawrence, and Matthew Slaughter, Succeeding in the Global Economy, Financial Services Forum Policy Research, June 2007, p. 10.

The infant-industry argument for trade protection holds that new industries need to be protected from foreign competition until they develop and flourish.

The national defense argument is fine as far as it goes, but it poses a clear danger: Even industries with the most peripheral relationship to defense are likely to invoke this argument on their behalf. For instance, for years the U.S. watchmaking industry argued for protection on the grounds that its skilled craftsmen would be invaluable in wartime!

Similarly, the United States has occasionally banned either exports to or imports from nations such as Cuba, Iran, and Iraq on political grounds. Such actions may have important economic effects, creating either bonanzas or disasters for particular American industries. But they are justified by politics, not by economics. Noneconomic reasons also explain quotas on importation of whaling products and on the furs of other endangered species.

The Infant-Industry Argument

Yet a fourth common rationale for protectionism is the so-called infant-industry argument, which has been prominent in the United States at least since Alexander Hamilton wrote his Report on Manufactures. Promising new industries often need breathing room to flourish and grow. If we expose these infants to the rigors of international competition too soon, the argument goes, they may never develop to the point where they can survive on their own in the international marketplace.

This argument, although valid in certain instances, is less defensible than it seems at first. Protecting an infant industry is justifiable only if the prospective future gains are sufficient to repay the up-front costs of protectionism. But if the industry is likely to be so profitable in the future, why doesn’t private capital rush in to take advantage of the prospective net profits? After all, the annals of business are full of cases in which a new product or a new firm lost money at first but profited handsomely later on. In recent times, Apple, Yahoo, Google, and eBay all lost money in their early days.

The infant-industry argument for protection stands up to scrutiny only if private funds are unavailable for some reason, despite an industry’s glowing profit prospects. Even then

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 17 |

International Trade and Comparative Advantage |

353 |

it may make more sense to provide a government loan rather than to provide trade protection.

In an advanced economy such as ours, with well-developed capital markets to fund new businesses, it is difficult to think of legitimate examples where the infant-industry argument applies. Even if such a case were found, we would have to be careful that the industry not remain in diapers forever. In too many cases, industries are awarded protection when young and, somehow, never mature to the point where protection can be withdrawn. We must be wary of infants that never grow up.

Strategic Trade Policy

A stronger argument for (temporary) protection has substantially influenced trade policy in the United States and elsewhere. Proponents of this line of thinking agree that free trade for all is the best system. But they point out that we live in an imperfect world in which many nations refuse to play by the rules of the free-trade game. And they fear that a nation that pursues free trade in a protectionist world is likely to lose out. It therefore makes sense, they argue, to threaten to protect your markets unless other nations agree to open theirs.

The United States has followed this strategy in trade negotiations with several countries in recent years. In one prominent case, the U.S. government threatened to impose high tariffs on several European luxury goods unless Europe opened its markets to imported bananas from the Americas. A few years later, the European Union turned the tables, threatening to increase tariffs on a variety of U.S. goods unless we changed a tax provision that amounted to an export subsidy. In each case, a dangerous trade war was narrowly averted when an agreement was struck at the eleventh hour.

The strategic argument for protection is a difficult one for economists to counter. Although it recognizes the superiority of free trade, it argues that threatening protectionism is the best way to achieve that end. (See the box “Can Protectionism Save Free Trade?”) Such a strategy might work, but it clearly involves great risks. If threats that the United States will turn protectionist induce other countries to scrap their existing protectionist policies, then the gamble will have succeeded. But if the gamble fails, protectionism increases.

The strategic argument for protection holds that a nation may sometimes have to threaten protectionism to induce other countries to drop their own protectionist measures.

CAN CHEAP IMPORTS HURT A COUNTRY?

One of the most curious—and illogical—features of the protectionist position is the fear of low import prices. Countries that subsidize their exports are often accused of dumping— of getting rid of their goods at unjustifiably low prices. Economists find this argument strange. As a nation of consumers, we should be indignant when foreigners charge us high prices, not low ones. That common-sense rule guides every consumer’s daily life. Only from the topsy-turvy viewpoint of an industry seeking protection are low prices seen as counter to the public interest.

Ultimately, the best interests of any country are served when its imports are as cheap as possible. It would be ideal for the United States if the rest of the world were willing to provide us with goods at no charge. We could then live in luxury at the expense of other countries.

But, of course, benefits to the United States as a whole do not necessarily accrue to every single American. If quotas on, say, sugar imports were dropped, American consumers and industries that purchase sugar would gain from lower prices. At the same time, however, owners of sugar fields and their employees would suffer serious losses in the form of lower profits, lower wages, and lost jobs—losses they would fight fiercely to prevent. For this reason, politics often leads to the adoption of protectionist measures that would likely be rejected on strictly economic criteria.

Dumping means selling goods in a foreign market at lower prices than those charged in the home market.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

354 |

PART 4 |

The United States in the World Economy |

AISSUE: |

LAST LOOK AT THE “CHEAP FOREIGN LABOR” ARGUMENT |

|

|

The preceding discussion reveals the fundamental fallacy in the argument that the United States as a whole should fear cheap foreign labor. The average American worker’s living standard must rise, not fall, if other countries willingly supply their products to us more cheaply. As long as the government’s monetary and fiscal policies succeed in maintaining high levels of employment, we cannot possibly lose by getting world products at bargain prices. Indeed, this is pre-

cisely what happened to the U.S. economy in the late 1990s. Even though imports poured in at low prices, unemployment in the United States fell to its lowest rate in a generation. Even in 2007, with a financial crisis and a massive trade deficit equal to 5.1 percent of GDP, the U.S. unemployment rate averaged only 4.6 percent.

We must add a few important qualifications, however. First, our macroeconomic policy may not always be effective. If workers displaced by foreign competition cannot find new jobs, they will indeed suffer from international trade. But high unemploy-

Can Protectionism Save Free Trade?

In this classic column, William Safire shook off his long-standing attachment to free trade and argued eloquently for retaliation against protectionist nations.

Free trade is economic motherhood. Protectionism is economic evil incarnate. . . . Never should government interfere in the efficiency of international competition.

Since childhood, these have been the tenets of my faith. If it meant that certain businesses in this country went belly-up, so be it. . . . If it meant that Americans would be thrown out of work by overseas companies paying coolie wages, that was tough. . . .

The thing to keep in mind, I was taught, was the Big Picture and the Long Run. America, the great exporter, had far more to gain than to lose from free trade; attempts to protect inefficient industries here would ultimately cost more American jobs.

While playing with my David Ricardo doll and learning nursery rhymes about comparative advantage, I was listening to another laissez-fairy tale: Government’s role in the world of business should be limited to keeping business honest and competitive. In God we antitrusted. Let businesses operate in the free marketplace.

Now American businesses are no longer competing with foreign companies. They are competing with foreign governments who help their local businesses. That means the world arena no longer offers a free marketplace; instead, most other governments are pushing a policy that can be called helpfulism.

Helpfulism works like this: A government like Japan decides to get behind its baseball-bat industry. It pumps in capital, knocks off marginal operators, finds subtle ways to discourage imports of Louisville Sluggers, and selects target areas for export blitzes. Pretty soon, the favored Japanese companies are driving foreign competitors batty.

How do we compete with helpfulism? One way is to complain that it is unfair; that draws a horselaugh. Another way is to demand a “Reagan Round” of trade negotiations under GATT, the Gentlemen’s Agreement To Talk, which is equally laughable.

Yet another way is to join the helpfuls by subsidizing our exports and permitting our companies to try monopolistic tricks abroad not permitted at home. But all that makes us feel guilty, with good reason.

The other way to deal with helpfulism is through—here comes the dreadful word—protection. Or, if you prefer a euphemism, retaliation. Or if that is still too severe, reciprocity. Whatever its name, it is a way of saying to the cutthroat cartelists we sweetly call our trading partners: “You have bent the rules out of shape. Change your practices to conform to the agreed-upon rules, or we will export a taste of your own medicine.”

A little balance, then, from the free trade theorists. The demand for what the Pentagon used to call “protective reaction” is not demagoguery, not shortsighted, not self-defeating. On the contrary, the overseas pirates of protectionism and exemplars of helpfulism need to be taught the basic lesson in trade, which is: tit for tat.

SOURCE: © David Burnett/Contact Press Images

SOURCE: William Safire, “Smoot-Hawley Lives,” The New York Times, March 17, 1983. Copyright © 1983 by The New York Times Company. Reprinted by permission.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 17 |

International Trade and Comparative Advantage |

355 |

ment reflects a shortcoming of the government’s monetary and fiscal policies, not of its international trade policies.

Second, we have noted that an abrupt stiffening of foreign competition can hurt U.S. workers by not allowing them adequate time to adapt to the new conditions. If change occurs fairly gradually, workers can be retrained and move into the industries that now require their services. Indeed, if the change is slow enough, normal attrition may suffice. But competition that inflicts its damage overnight is certain to impose real costs on the affected workers—costs that are no less painful for being temporary. That is why our trade laws make provisions for people and industries damaged by import surges.

In fact, the economic world is constantly changing. The recent emergence of China, India, and other third-world countries, for example, has created stiff new competition for workers in America and other rich nations—competition they never imagined when they signed up for jobs that may now be imperiled by international trade. The same is true of many workers in service jobs (ranging from call center operators to lawyers) who never dreamed that their jobs might be done electronically from thousands of miles away. It is not irrational, and it is certainly not protectionist, for countries like the United States to use trade adjustment assistance and other tools to cushion the blow for these workers.

But these are, after all, only qualifications to an overwhelming argument. They call for intelligent monetary and fiscal policies and for transitional assistance to unemployed workers, not for abandonment of free trade. In general, the nation as a whole need not fear competition from cheap foreign labor.

In the long run, labor will be “cheap” only where it is not very productive. Wages will be high in countries with high labor productivity, and this high productivity will enable those countries to compete effectively in international trade despite their high wages. It is thus misleading to say that the United States held its own in the international marketplace until recently despite high wages. Rather, it is much more accurate to note that the higher wages of American workers were a result of higher

Unfair Foreign Competition

Satire and ridicule are often more persuasive than logic and statistics. Exasperated by the spread of protectionism under the prevailing mercantilist philosophy, the French economist Frédéric Bastiat decided to take the protectionist argument to its illogical conclusion. The fictitious petition of the French candlemakers to the Chamber of Deputies, written in 1845 and excerpted below, has become a classic in the battle for free trade.

We are subject to the intolerable competition of a foreign rival, who enjoys, it would seem, such superior facilities for the production of light, that he is enabled to inundate our national market at so exceedingly reduced a price, that, the moment he makes his appearance, he draws off all custom for us; and thus an important branch of French industry, with all its innumerable ramifications, is suddenly reduced to a state of complete stagnation. This rival is no other than the sun.

Our petition is, that it would please your honorable body to pass a law whereby shall be directed the shutting up of all windows, dormers, skylights, shutters, curtains, in a word, all openings, holes, chinks, and fissures through which the light of the sun is used to penetrate our dwellings, to the prejudice of the profitable manufactures which we flatter ourselves we have been enabled to bestow upon the country. . . .

We foresee your objections, gentlemen; but there is not one that you can oppose to us . . . which is not equally opposed to your own practice and the principle which guides your policy. . . . Labor and nature concur in different proportions, according to country and climate, in every article of production. . . . If a Lisbon orange can be sold at half the price of a Parisian one, it is because a natural and gratuitous heat does for the one what the other only obtains from an artificial and consequently expensive one. . . .

Does it not argue the greatest inconsistency to check as you do the importation of coal, iron, cheese, and goods of foreign manufacture, merely because and even in proportion as their price approaches zero, while at the same time you freely admit, and without limitation, the light of the sun, whose price is during the whole day at zero?

SOURCE: F. Bastiat, Economic Sophisms (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1922).

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

356 |

PART 4 |

The United States in the World Economy |

worker productivity, which gave the United States a major competitive edge—an edge we still have, by the way.

Remember, where standards of living are concerned, it is absolute advantage, not comparative advantage, that counts. The country that is most efficient in producing every output can pay its workers more in every industry.

| SUMMARY |

1.Countries trade for many reasons. Two of the most important are that differences in their natural resources and other inputs create discrepancies in the efficiency with which they can produce different goods, and that specialization offers greater economies of large-scale production.

2.Voluntary trade will generally be advantageous to both parties in an exchange. This concept is one of our Ideas for Beyond the Final Exam.

3.International trade is more complicated than trade within a nation because of political factors, differing national currencies, and impediments to the movement of labor and capital across national borders.

4.Two countries will gain from trade with each other if each nation exports goods in which it has a comparative advantage. Even a country that is inefficient across the board will benefit by exporting the goods in whose production it is least inefficient. This concept is another of the

Ideas for Beyond the Final Exam.

5.When countries specialize and trade, each can enjoy consumption possibilities that exceed its production possibilities.

6.The “cheap foreign labor” argument ignores the principle of comparative advantage, which shows that real wages (which determine living standards) can rise in both importing and exporting countries as a result of specialization.

7.Tariffs and quotas aim to protect a country’s industries from foreign competition. Such protection may sometimes be advantageous to that country, but not if foreign countries adopt tariffs and quotas of their own in retaliation.

8.From the point of view of the country that imposes them, tariffs offer at least two advantages over quotas: Some of the gains go to the government rather than to foreign producers, and they provide greater incentive for efficient production.

9.When a nation eliminates protection in favor of free trade, some industries and their workers will lose out. Equity then demands that these people and firms be compensated in some way. The U.S. government offers protection from import surges and various forms of trade adjustment assistance to help those workers and industries adapt to the new conditions.

10.Several arguments for protectionism can, under the right circumstances, have validity. They include the national defense argument, the infant-industry argument, and the use of trade restrictions for strategic purposes. But each of these arguments is frequently abused.

11.Dumping will hurt certain domestic producers, but it benefits domestic consumers.

| KEY TERMS |

“Cheap foreign labor” |

|

Absolute advantage 343 |

Trade adjustment assistance 351 |

||||

argument 340 |

|

Comparative advantage 343 |

Infant-industry argument 352 |

||||

|

|

|

|||||

Imports |

340 |

|

Mercantilism |

348 |

Strategic argument for |

||

|

|

|

|||||

Exports |

340 |

|

Tariff |

348 |

|

protection |

353 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Specialization 341 |

|

Quota |

348 |

|

Dumping |

353 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Mutual gains from trade |

341 |

Export subsidy |

349 |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.