Baumol & Blinder MACROECONOMICS (11th ed)

.pdf

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 12 |

Money and the Banking System |

257 |

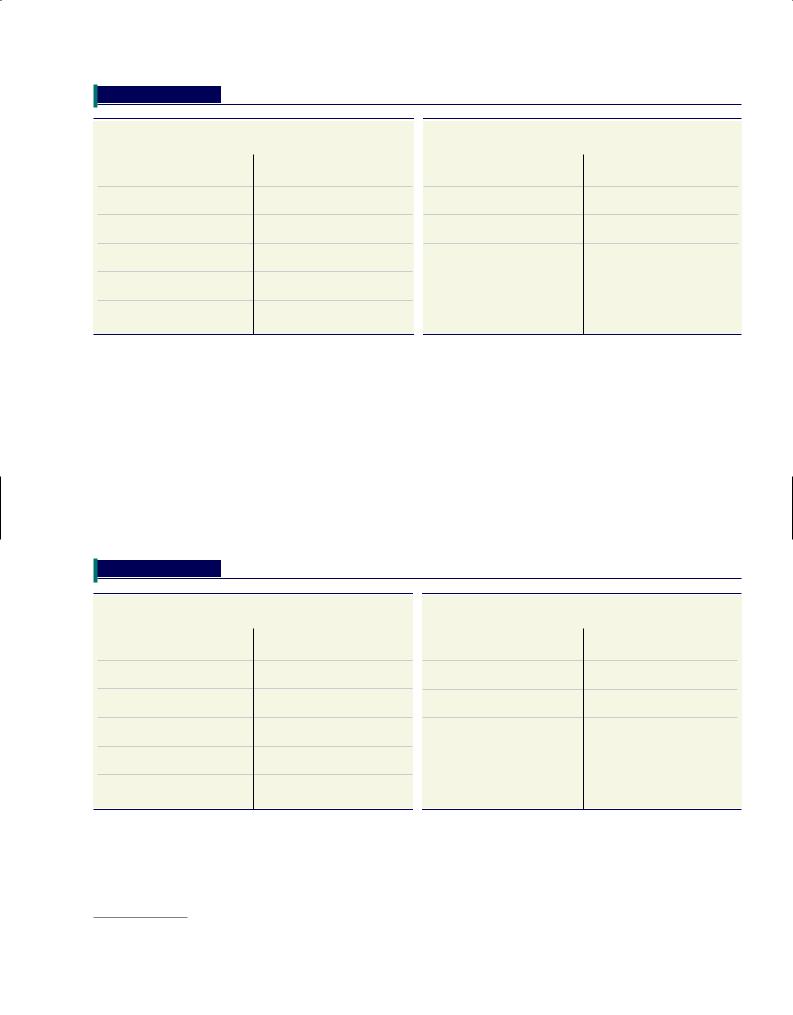

TABLE 7

Changes in the Balance Sheet of Bank-a-mythica

(A)

|

ASSETS |

|

LIABILITIES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Checking |

|

Reser ves |

2$100,000 |

deposits |

2$100,000 |

Addendum: Changes

in Reserves

Actual

reser ves 2$100,000

Required

reser ves 2$20,000

Excess

reser ves 2$80,000

|

|

(B) |

|

ASSETS |

LIABILITIES |

|

|

|

Reser ves |

1$80,000 |

No Change |

Loans

outstanding 2$80,000

Addendum: Changes

in Reserves

Actual |

|

reser ves |

1$80,000 |

Required |

|

reser ves |

No Change |

Excess |

|

reser ves |

1$80,000 |

How would the bank react to this discrepancy? As some of its outstanding loans are routinely paid off, it will cease granting new ones until it has accumulated the necessary $80,000 in required reserves. The data for Bank-a-mythica’s contraction are shown in Table 7(b), assuming that borrowers pay off their loans in cash.5

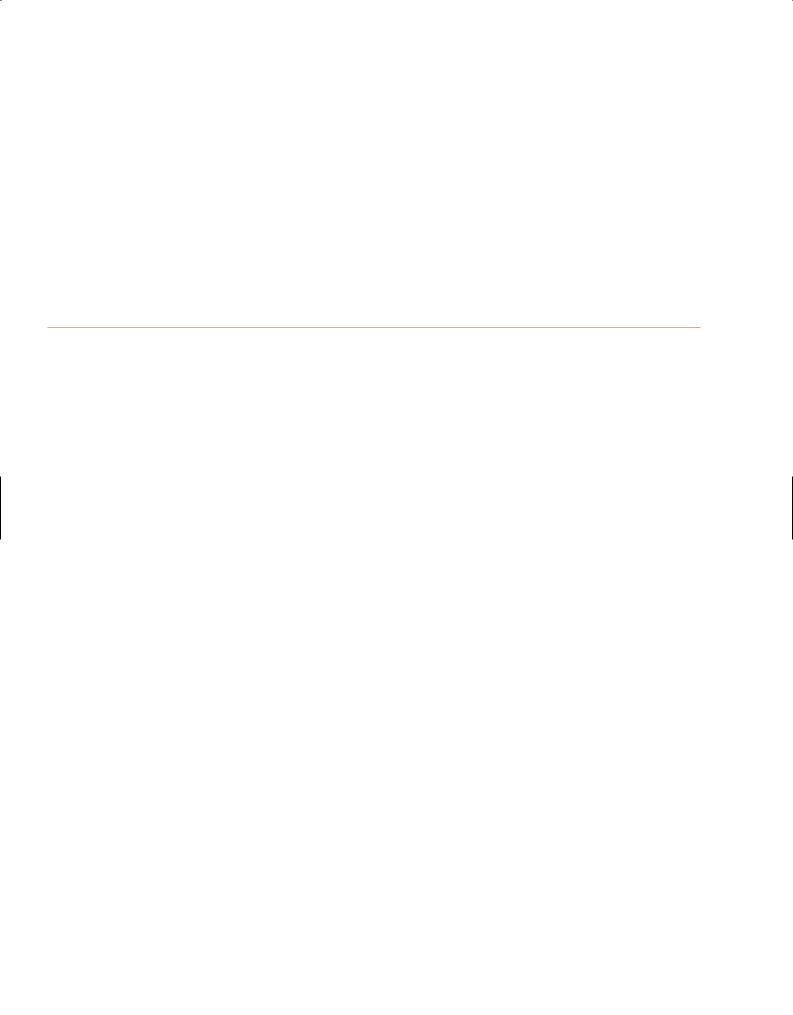

But where did the borrowers get this money? Probably by making withdrawals from other banks. In this case, assume that the funds came from First National Bank, which loses $80,000 in deposits and $80,000 in reserves. It finds itself short some $64,000 in reserves, as shown in Table 8(a), and therefore must reduce its loan commitments by $64,000, as in Table 8(b). This reaction, of course, causes some other bank to suffer a loss of reserves and deposits of $64,000, and the whole process repeats just as it did in the case of deposit expansion.

TABLE 8

Changes in the Balance Sheet of First National Bank

(A)

|

ASSETS |

|

LIABILITIES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Checking |

|

Reser ves |

2$80,000 |

deposits |

2$80,000 |

Addendum: Changes

in Reserves

Actual

reser ves 2$80,000

Required

reser ves 2$16,000

Excess

reser ves 2$64,000

|

|

(B) |

|

ASSETS |

LIABILITIES |

|

|

|

Reser ves |

1$64,000 |

No Change |

Loans

outstanding 2$64,000

Addendum: Changes

in Reserves

Actual |

|

reser ves |

1$64,000 |

Required |

|

reser ves |

No Change |

Excess |

|

reser ves |

1$64,000 |

After the entire banking system had become involved, the picture would be just as shown in Figure 3, except that all the numbers would have minus signs in front of them. Deposits would shrink by $500,000, loans would fall by $400,000, bank reserves would be reduced by $100,000, and the M1 money supply would fall by $400,000. As suggested by

5 In reality, the borrowers would probably pay with checks drawn on other banks. Bank-a-mythica would then cash these checks to acquire the reserves.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

258 |

PART 3 |

Fiscal and Monetary Policy |

our money multiplier formula with m 5 0.20, the decline in the bank deposit component of the money supply is 1/0.20 5 5 times as large as the decline in reserves.

One of the authors of this book was a student in Cambridge, Massachusetts, during the height of the radical student movement of the late 1960s. One day a pamphlet appeared urging citizens to withdraw all funds from their checking accounts on a prescribed date, hold them in cash for a week, and then redeposit them. This act, the circular argued, would wreak havoc upon the capitalist system. Obviously, some of these radicals were well schooled in modern money mechanics, for the argument was basically correct. The tremendous multiple contraction of the banking system and subsequent multiple expansion that a successful campaign of this sort could have caused might have seriously disrupted the local financial system. But history records that the appeal met with little success. Apparently, checking account withdrawals are not the stuff of which revolutions are made.

WHY THE MONEY-CREATION FORMULA IS OVERSIMPLIFIED

So far, our discussion of the process of money creation has seemed rather mechanical. If everything proceeds according to formula, each $1 in new reserves injected into the banking system leads to a $1/m increase in new deposits. But, in reality, things are not this simple. Just as in the case of the expenditure multiplier, the oversimplified money multiplier is accurate only under very particular circumstances. These circumstances require that

1.Every recipient of cash must redeposit the cash into another bank rather than hold it.

2.Every bank must hold reserves no larger than the legal minimum.

The “chain” diagram in Figure 3 on page 255 can teach us what happens if either of these assumptions is violated.

Suppose first that the business firms and individuals who receive bank loans decide to redeposit only a fraction of the proceeds into their bank accounts, holding the rest in cash. Then, for example, the first $80,000 loan would lead to a deposit of less than $80,000— and similarly down the chain. The whole chain of deposit creation would therefore be reduced. Thus:

If individuals and business firms decide to hold more cash, the multiple expansion of bank deposits will be curtailed because fewer dollars of cash will be available for use as reserves to support checking deposits. Consequently, the money supply will be smaller.

The basic idea here is simple. Each $1 of cash held inside a bank can support several dollars (specifically, $1/m) of money. But each $1 of cash held outside the banking system is exactly $1 of money; it supports no deposits. Hence, any time cash moves from inside the banking system into the hands of a household or a business, the money supply will decline. And any time cash enters the banking system, the money supply will rise.

Next, suppose bank managers become more conservative or that the outlook for loan repayments worsens because of a recession. In such an environment, banks might decide to keep more reserves than the legal requirement and lend out less than the amounts assumed in Figure 3. If this happens, banks further down the chain receive smaller deposits and, once again, the chain of deposit creation is curtailed. Thus:

If banks wish to keep excess reserves, the multiple expansion of bank deposits will be limited. A given amount of cash will support a smaller supply of money than would be the case if banks held no excess reserves.

The latter problem afflicted Japan for many years in the 1990s and continuing into this decade. Because they had so many bad loans on their books, Japanese bankers became supercautious about lending money to any but their most creditworthy borrowers. So even though bank reserves soared, the money supply did not. Something similar happened in the U.S. in 2007 and 2008, when banks got jittery.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 12 |

Money and the Banking System |

259 |

THE NEED FOR MONETARY POLICY

If we pursue these two points a bit farther, we will see why the government must regulate the money supply in an effort to maintain economic stability. We have just suggested that banks prefer to keep excess reserves when they do not foresee profitable and secure opportunities to make loans. This scenario is most likely to arise when business conditions are depressed. At such times, the propensity of banks to hold excess reserves can turn the deposit-creation process into one of deposit destruction, as happened recently in the U.S. and elsewhere. In addition, if depositors become nervous, they may decide to hold on to more cash. Thus:

During a recession, profit-oriented banks would be prone to reduce the money supply by increasing their excess reserves and declining to lend to less creditworthy applicants—if the government did not intervene. As we will learn in subsequent chapters, the money supply is an important influence on aggregate demand, so such a contraction of the money supply would aggravate the recession.

This is precisely what happened—with a vengeance—during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Although total bank reserves grew, the money supply contracted violently because banks preferred to hold excess reserves rather than make loans that might not be repaid. And something similar has been happening in Japan for years: The supply of reserves has expanded much more rapidly than the money supply because nervous bankers have been holding on to their excess reserves.

By contrast, banks want to squeeze the maximum money supply possible out of any given amount of cash reserves by keeping their reserves at the bare minimum when the demand for bank loans is buoyant, profits are high, and secure investment opportunities abound. This reduced incentive to hold excess reserves in prosperous times means that

During an economic boom, profit-oriented banks will likely make the money supply expand, adding undesirable momentum to the booming economy and paving the way for inflation. The authorities must intervene to prevent this rapid money growth.

Regulation of the money supply, then, is necessary because profit-oriented bankers might otherwise provide the economy with a money supply that dances to and amplifies the tune of the business cycle. Precisely how the authorities control the money supply is the subject of the next chapter.

| SUMMARY |

1.It is more efficient to exchange goods and services by using money as a medium of exchange than by bartering them directly.

2.In addition to being the medium of exchange, whatever serves as money is likely to become the standard unit of account and a popular store of value.

3.Throughout history, all sorts of items have served as money. Commodity money gave way to full-bodied paper money (certificates backed 100 percent by some commodity, such as gold), which in turn gave way to partially backed paper money. Nowadays, our paper money has no commodity backing whatsoever; it is pure fiat money.

4.One popular definition of the U.S. money supply is M1, which includes coins, paper money, and several types of checking deposits. Most economists prefer the M2 definition, which adds to M1 other types of checkable accounts and most savings deposits. Much of M2 is held

outside of banks by investment houses, credit unions, and other financial institutions.

5.Under our modern system of fractional reserve banking, banks keep cash reserves equal to only a fraction of their total deposit liabilities. This practice is the key to their profitability, because the remaining funds can be loaned out at interest. But it also leaves banks potentially vulnerable to runs.

6.Because of this vulnerability, bank managers are generally conservative in their investment strategies. They also keep a prudent level of reserves. Even so, the government keeps a watchful eye over banking practices.

7.Before 1933, bank failures were common in the United States. They declined sharply when deposit insurance was instituted.

8.Because it holds only fractional reserves, the banking system as a whole can create several dollars of deposits for each dollar of reserves it receives. Under

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

260 |

PART 3 |

Fiscal and Monetary Policy |

certain assumptions, the ratio of new bank deposits to new reserves will be $1/m, where m is the required reserve ratio.

9.The same process works in reverse, as a system of money destruction, when cash is withdrawn from the banking system.

10.Because banks and individuals may want to hold more cash when the economy is shaky, the money supply would probably contract under such circumstances if the government did not intervene. Similarly, the money supply would probably expand rapidly in boom times if it were unregulated.

| KEY TERMS |

Run on a bank |

242 |

|

M2 247 |

|

|

Asset 251 |

|

|

||

Barter |

243 |

|

|

Near moneys |

247 |

|

Liability 251 |

|

|

|

Money |

244 |

|

|

Liquidity 247 |

|

|

Balance sheet |

252 |

||

Medium of exchange |

244 |

Fractional reserve banking 248 |

Net worth 252 |

|

||||||

Unit of account |

244 |

Deposit insurance |

250 |

Deposit creation |

252 |

|||||

Store of value |

244 |

|

Moral hazard |

250 |

|

Excess reserves |

252 |

|||

Commodity money |

245 |

Federal Deposit Insurance |

Money multiplier |

256 |

||||||

Fiat money 246 |

|

Corporation (FDIC) |

250 |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

M1 |

247 |

|

|

Required reserves |

251 |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| TEST YOURSELF |

1.Suppose banks keep no excess reserves and no individuals or firms hold on to cash. If someone suddenly discovers $12 million in buried treasure and deposits it in a bank, explain what will happen to the money supply if the required reserve ratio is 10 percent.

2.How would your answer to Test Yourself Question 1 differ if the reserve ratio were 25 percent? If the reserve ratio were 100 percent?

3.Use tables such as Tables 2 and 3 to illustrate what happens to bank balance sheets when each of the following transactions occurs:

a.You withdraw $100 from your checking account to buy concert tickets.

b.Sam finds a $100 bill on the sidewalk and deposits it into his checking account.

c.Mary Q. Contrary withdraws $500 in cash from her account at Hometown Bank, carries it to the city, and deposits it into her account at Big City Bank.

4.For each of the transactions listed in Test Yourself Question 3, what will be the ultimate effect on the money supply if the required reserve ratio is one-eighth (12.5 percent)? Assume that the oversimplified money multiplier formula applies.

| DISCUSSION QUESTIONS |

1.If ours were a barter economy, how would you pay your tuition bill? What if your college did not want the goods or services you offered in payment?

2.How is “money” defined, both conceptually and in practice? Does the U.S. money supply consist of commodity money, full-bodied paper money, or fiat money?

3.What is fractional reserve banking, and why is it the key to bank profits? (Hint: What opportunities to make profits would banks lose if reserve requirements were 100 percent?) Why does fractional reserve banking give bankers discretion over how large the money supply will be? Why does it make banks potentially vulnerable to runs?

4.During the 1980s and early 1990s, a rash of bank failures occurred in the United States. Explain why these failures did not lead to runs on banks.

5.Each year during Christmas shopping season, consumers and stores increase their holdings of cash. Explain how this development could lead to a multiple contraction of the money supply. (As a matter of fact, the authorities prevent this contraction from occurring by methods explained in the next chapter.)

6.Excess reserves make a bank less vulnerable to runs. Why, then, don’t bankers like to hold excess reserves? What circumstances might persuade them that it would be advisable to hold excess reserves?

7.If the government takes over a failed bank with liabilities (mostly deposits) of $2 billion, pays off the depositors, and sells the assets for $1.5 billion, where does the missing $500 million come from? Why?

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

MANAGING AGGREGATE DEMAND:

MONETARY POLICY

Victorians heard with grave attention that the Bank Rate had been raised. They did not know what it meant. But they knew that it was an act of extreme wisdom.

JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH

A rmed with our understanding of the rudiments of banking, we are now ready to bring money and interest rates into our model of income determination and the price level. Up to now, we have taken investment (I) to be a fixed number. But this is a poor assumption. Not only is investment highly variable but it also depends on interest rates—which are, in turn, heavily influenced by monetary policy. The main task of this chapter is to explain how monetary policy affects interest rates, investment, and aggregate demand. By the end of the chapter, we will have constructed a complete macroeconomic model, which we will use in subsequent chapters to investigate a vari-

ety of important policy issues.

Monetary policy refers to actions that the Federal Reserve System takes to change interest rates and the money supply. It is aimed at affecting the economy.

C O N T E N T S

ISSUE: JUST WHY IS BEN BERNANKE SO |

The Market for Bank Reserves |

MONEY AND THE PRICE LEVEL IN THE |

|

IMPORTANT? |

The Mechanics of an Open-Market Operation |

KEYNESIAN MODEL |

|

MONEY AND INCOME: THE IMPORTANT |

Open-Market Operations, Bond Prices, |

Application: Why the Aggregate Demand Curve |

|

and Interest Rates |

Slopes Downward |

||

DIFFERENCE |

|||

|

|

||

AMERICA’S CENTRAL BANK: THE FEDERAL |

OTHER METHODS OF MONETARY CONTROL |

FROM MODELS TO POLICY DEBATES |

|

Lending to Banks |

|

||

RESERVE SYSTEM |

|

||

|

|

||

Origins and Structure |

Changing Reserve Requirements |

|

|

|

|

||

Central Bank Independence |

HOW MONETARY POLICY WORKS |

|

|

IMPLEMENTING MONETARY POLICY: |

Investment and Interest Rates |

|

|

|

|

||

OPEN-MARKET OPERATIONS |

Monetary Policy and Total Expenditure |

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO: |

|

|

|

|

262 |

PART 3 Fiscal and Monetary Policy |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ISSUE: |

JUST WHY IS BEN BERNANKE SO IMPORTANT? |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 had been simmering below the surface for a |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

while. But when it burst into the open in August 2007, every eye in the finan- |

|

|

|

|

cial world, it seemed, turned to Ben Bernanke, who had been installed as |

|

|

|

|

chairman of the Federal Reserve Board just 18 months earlier. Why? Because |

|

|

|

|

many observers see the Federal Reserve chairman as the most powerful per- |

|

|

|

|

son in the economic world. |

|

|

|

Bernanke is a brilliant but unassuming economist who taught for many years at |

||

|

|

Princeton University. But now when he speaks, people in financial markets around the |

||

|

|

world dote on his remarks with an intensity that was once reserved for utterances from |

||

|

|

behind the Kremlin walls. The reason for all the attention is that, in the view of many |

||

|

|

economists, the Federal Reserve’s decisions on interest rates are the single most impor- |

||

|

|

tant influence on aggregate demand—and hence on economic growth, unemployment, |

||

|

|

|

|

and inflation. And the financial crisis made |

|

|

|

|

people worried about the health of the |

|

|

|

|

economy. |

|

|

|

|

Bernanke heads America’s central |

|

|

|

www |

bank, the Federal Reserve System. The |

|

|

|

“Fed,” as it is called, is a bank—but a very |

|

|

|

|

from |

|

|

|

|

special kind of bank. Its customers are |

|

|

|

|

obtainable |

|

|

|

|

banks rather than individuals, and it per- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

rights |

forms some of the same services for them |

|

|

|

as your bank performs for you. Although |

|

|

|

|

Reproduction |

it makes enormous profits, profit is not its |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

goal. Instead, the Fed tries to manage in- |

|

|

|

Schwadron.Harley©SOURCE: .CartoonStock.com |

terest rates according to what it perceives |

|

|

|

ever Ben Bernanke speaks. |

|

to be the national interest. This chapter will teach you how the Fed does its job and why its decisions affect our economy so profoundly. In brief, it will teach you why people listen so intently when-

MONEY AND INCOME: THE IMPORTANT DIFFERENCE

But first we must get some terminology straight. The words money and income are used almost interchangeably in common parlance. Here, however, we must be more precise.

Money is a snapshot concept. It answers questions such as “How much money do you have right now?” or “How much money did you have at 3:32 P.M. on Friday, November 5?” To answer these questions, you would add up the cash you are (or were) carrying and whatever checkable balances you have (or had), and answer something like: “I have $126.33,” or “On Friday, November 5, at 3:32 P.M., I had $31.43.”

Income, by contrast, is more like a motion picture; it comes to you over a period of time. If you are asked, “What is your income?”, you must respond by saying “$1,000 per week,” or “$4,000 per month,” or “$50,000 per year,” or something like that. Notice that a unit of time is attached to each of these responses. If you just answer, “My income is $45,000,” without indicating whether it is per week, per month, or per year, no one will understand what you mean.

That the two concepts are very different is easy to see. A typical American family has an income of about $45,000 per year, but its money holdings at any point in time (using the M1 definition) may be less than $2,000. Similarly, at the national level, nominal GDP at the end of 2007 was around $14 trillion, while the money stock (M1) was under $1.4 trillion.

Although money and income are different, they are certainly related. This chapter focuses on that relationship. Specifically, we will look at how interest rates and the stock of money in existence at any moment of time influences the rate at which people earn income—that is, how monetary policy affects GDP.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 13 |

Managing Aggregate Demand: Monetary Policy |

263 |

AMERICA’S CENTRAL BANK: THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

When Congress established the Federal Reserve System in 1914, the United States joined the company of most other advanced industrial nations. Until then, the United States, distrustful of centralized economic power, was almost the only important nation without a central bank. The Bank of England, for example, dates back to 1694.

Origins and Structure

It was painful experiences with economic reality, not the power of economic logic, that provided the impetus to establish a central bank for the United States. Four severe banking panics between 1873 and 1907, in which many banks failed, convinced legislators and bankers alike that a central bank that would regulate credit conditions was not a luxury but a necessity. The 1907 crisis led Congress to study the shortcomings of the banking system and, eventually, to establish the Federal Reserve System.

Although the basic ideas of central banking came from Europe, the United States made some changes when it imported the idea, making the Federal Reserve System a uniquely American institution.1 Because of the vastness of our country, the extraordinarily large number of commercial banks, and our tradition of shared state-federal responsibilities, Congress decided that the United States should have not one central bank but twelve.

Technically, each Federal Reserve Bank is a corporation; its stockholders are its member banks. But your bank, if it is a member of the system, does not enjoy the privileges normally accorded to stockholders: It receives only a token share of the Federal Reserve’s immense profits (the bulk is turned over to the U.S. Treasury), and it has virtually no say in corporate decisions. In fact, the private banks are more like customers of the Fed than owners.

Who, then, controls the Fed? Most of the power resides in the seven-member Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington, and especially in its chairman. The governors are appointed by the President of the United States, with the advice and consent of the Senate, for fourteen-year terms. The president also designates one of the members to serve a four-year term as chairman of the board and thus to be the most powerful central banker in the world.

The Federal Reserve is independent of the rest of the government. As long as it stays within the authority granted to

it by Congress, it alone has responsibility for determining the nation’s monetary policy. The power of appointment, however, gives the president some long-run influence over Federal Reserve policy. For example, it was President George W. Bush in 2006 who selected Ben Bernanke, a former adviser, to be the Fed’s next chairman.

Closely allied with the Board of Governors is the powerful Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which meets eight times a year in Washington. For reasons to be explained shortly, FOMC decisions largely determine short-term interest rates and the size of the U.S. money supply. This twelve-member committee consists of the seven governors of the Federal Reserve System, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and, on a rotating basis, four of the other eleven district bank presidents.2

A central bank is a bank for banks. The United States’ central bank is the

Federal Reserve System.

1Ironically, when the European Central Bank was established in 1999, its structure was patterned on that of the Federal Reserve.

2Alan Blinder was the vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, and thus a member of the Federal Open Market Committee, from 1994 to 1996.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

264 |

PART 3 |

Fiscal and Monetary Policy |

A Meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee

Meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee are serious and formal affairs. All 19 members—7 governors and 12 reserve bank presidents—sit around a mammoth table in the Fed’s cavernous but austere board room. A limited number of top Fed staffers join them at and around the table, for access to FOMC meetings is strictly controlled.

At precisely 9 A.M.—for punctuality is a high virtue at the Fed— the doors are closed and the chairman calls the meeting to order. No press is allowed and, unlike most important Washington meetings, nothing said there will leak. Secrecy is another high virtue at the Fed.

After hearing a few routine staff reports, the chairman calls on each of the members in turn to give their views of the current economic situation. District bank presidents offer insights into their local economies, and all members comment on the outlook for the national economy. Committee members also offer their views on what changes in monetary policy, if any, are appropriate. Disagreements are raised, but voices are not, for politeness is another virtue. Strikingly, in this most political of cities, politics is almost never mentioned.

Once he has heard from all the others, the chairman summarizes the discussion, offers his own views of the economic situation and of the policy options, and recommends a course of action. Most members normally agree with the chairman, though some note differences of opinion. Then the chairman asks the

secretary to call the roll. Only the 12 voting members answer, saying yes or no. Negative votes are rare, for the FOMC tries to operate by consensus and a dissent is considered a loud objection.

The meeting adjourns, and at precisely 2:15 P.M. a Fed spokesman announces the decision to the public. Within minutes, financial markets around the world react.

SOURCE: Courtesy of the Federal Reserve Board

Central bank independence refers to the central bank’s ability to make decisions without political interference.

Central Bank Independence

For decades a debate raged, both in the United States and in other countries, over the pros and cons of central bank independence.

Proponents of central bank independence argued that it enables the central bank to take the long view and to make monetary policy decisions on objective, technical criteria—thus keeping monetary policy out of the “political thicket.” Without this independence, they argued, politicians with short time horizons might try to force the central bank to expand the money supply too rapidly, especially before elections, thereby contributing to chronic inflation and undermining faith in the country’s financial system. They pointed to historical evidence showing that countries with more independent central banks have, on average, experienced lower inflation.

Opponents of this view countered that there is something profoundly undemocratic about letting a group of unelected bankers and economists make decisions that affect every citizen’s well-being. Monetary policy, they argued, should be formulated by the elected representatives of the people, just as fiscal policy is.

The high inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s helped resolve this issue by convincing many governments around the world that an independent central bank was essential to controlling inflation. Thus, one country after another has made its central bank independent over the past 20 to 25 years. For example, the Maastricht Treaty (1992), which committed members of the European Union to both low inflation and a single currency (the euro), required each member state to make its central bank independent. All did so, even though several have still not joined the monetary union. Japan also decided to make its central bank independent in 1998. In Latin America, several formerly high-inflation

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 13 |

Managing Aggregate Demand: Monetary Policy |

265 |

countries like Brazil and Mexico found that giving their central banks more independence helped them control inflation. And some of the formerly socialist countries of Europe, finding themselves saddled with high inflation and “unsound” currencies, made their central banks more independent for similar reasons. Thus, for practical purposes, the debate over central bank independence is now all but over.

The new debate is over how to hold such independent and powerful institutions accountable to the political authorities and to the broad public. For example, most central banks have now abandoned their former traditions of secrecy and have become far more open to public scrutiny. Some, the “inflation targeters,” even announce specific numerical targets for inflation, thereby making it easy for outside observers to judge the central bank’s success or failure. The Federal Reserve does not do this explicitly, but it reveals enough information in its long-run forecast that people pretty much know its inflation target.

IMPLEMENTING MONETARY POLICY: OPEN-MARKET OPERATIONS

When it wants to change interest rates, the Fed normally relies on open-market operations, which is the tool it relied upon when it lowered interest rates in response to the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Open-market operations either give banks more reserves or take reserves away from them, thereby triggering the sort of multiple expansion or contraction of the money supply described in the previous chapter.

How does this process work? If the Federal Open Market Committee decides to lower interest rates, it can bring them down by providing banks with more reserves. Specifically, the Federal Reserve System would normally purchase a particular kind of short-term U.S. government security called a Treasury bill from any individual or bank that wished to sell them, paying with newly created bank reserves. To see how this open-market operation affects interest rates, we must understand how the market for bank reserves, which is depicted in Figure 1, works.

Open-market operations refer to the Fed’s purchase or sale of government securities through transactions in the open market.

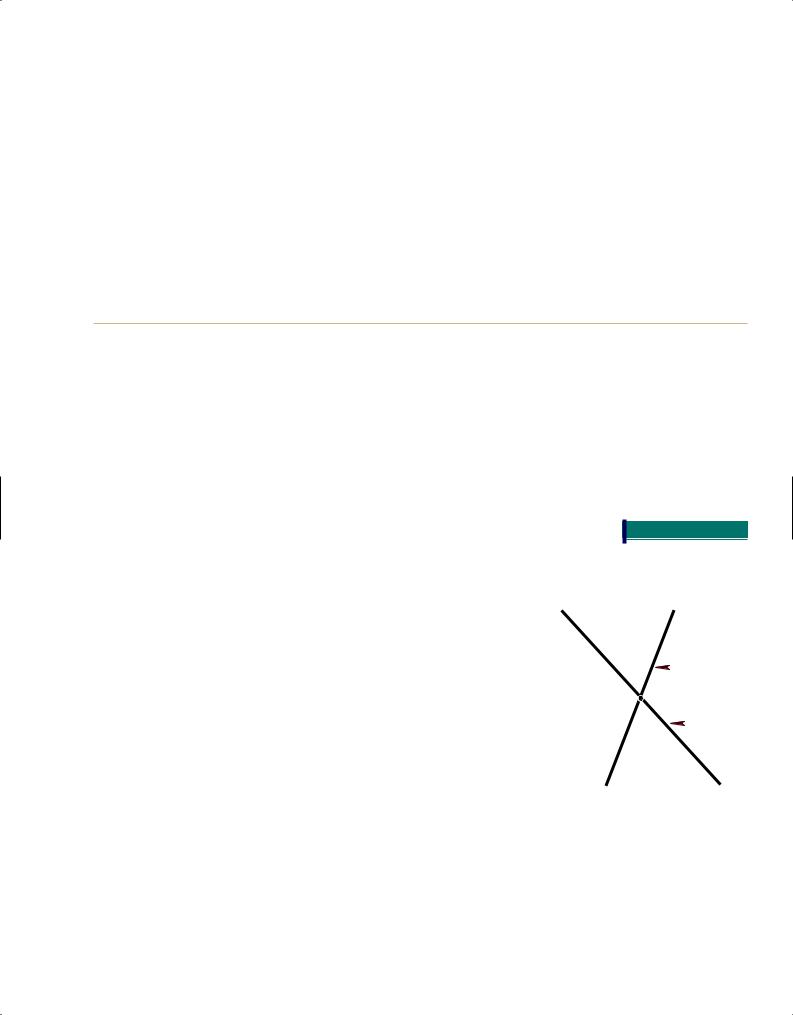

FIGURE 1

The Market for Bank Reserves

The Market for Bank Reserves |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The main sources of supply and demand in the market on which |

|

D |

S |

|||||

bank reserves are traded are straightforward. On the supply |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

side, the Fed decides how many dollars of reserves to provide. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus the label on the supply curve in Figure 1 indicates that the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

position of the supply curve depends on Federal Reserve policy. The |

Rate |

|

|

|

For given |

|||

|

|

|

||||||

Fed’s decision on the quantity of bank reserves is the essence of |

|

E |

|

Fed policy |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

monetary policy, and we are about to consider how the Fed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Interest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

makes that decision. |

|

|

|

|

For given Y |

|||

On the demand side of the market, the main reason why |

|

|

|

|

|

and P |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

banks hold reserves is something we learned in the previous |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chapter: Government regulations require them to do so. In Chap- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ter 12, we used the symbol m to denote the required reserve ratio |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(which is 0.1 in the United States). So if the volume of transaction |

|

S |

|

|

|

D |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

deposits is D, the demand for required reserves is simply m 3 D. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The demand for reserves thus reflects the demand for transac- |

|

Quantity of Bank Reserves |

||||||

tions deposits in banks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The demand for bank deposits depends on many factors, but the principal determinant is the dollar value of transactions. After all, people and businesses hold bank deposits in order to conduct transactions. Real GDP (Y) is typically used as a convenient indicator of the number of transactions, and the price level (P) is a natural measure of the average price per transaction. So the volume of bank deposits, D, and therefore the demand for bank reserves, depends on both Y and P—as indicated by the label on the demand curve in Figure 1.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

266 |

PART 3 |

Fiscal and Monetary Policy |

The federal funds rate is the interest rates that banks pay and receive when they borrow reserves from one another.

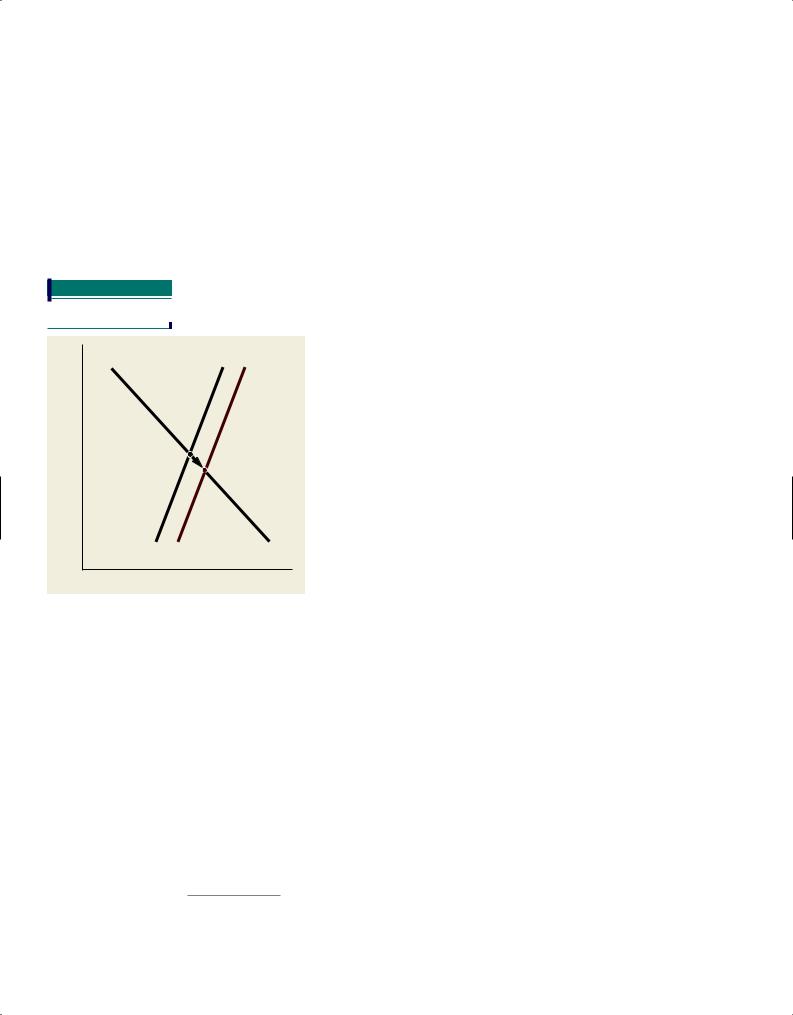

FIGURE 2

The Effects of an Open-

Market Purchase

D

Interest Rate

S0 S1

There is more to the story, however, for we have not yet explained why the the demand curve DD slopes down and the supply curve SS slopes up. The interest rate measured along the vertical axis of Figure 1 is called the federal funds rate. It is the rate that applies when banks borrow and lend reserves to one another. When you hear on the evening news that “the Federal Reserve today cut interest rates by 1⁄4 of a point today,” it is the federal funds rate that the reporter is talking about.

Now where does this borrowing and lending come from? As we mentioned in the previous chapter, banks sometimes find themselves with either insufficient or excess reserves. Neither situation leaves bankers happy. Keeping actual reserves below the required level is not allowed. Holding reserves in excess of requirements is perfectly legal, but since reserves pay no interest, a bank can put excess reserves to better use by lending them out rather than keeping them idle. So banks have developed an active market in which those with excess reserves lend them to those with reserve deficiencies. These bank-to-bank loans provide an additional source of both supply and demand—and one that (unlike required reserves) is interest sensitive.

|

Any bank that wants to borrow reserves must pay the federal |

|

|

funds rate for the privilege. Naturally, as the funds rate rises, bor- |

|

S0 S1 |

rowing looks more expensive and so fewer reserves are de- |

|

|

manded. In a word, the demand curve for reserves (DD) slopes |

|

|

downward. Similarly, the supply curve for reserves (SS) slopes |

|

|

upward because lending reserves becomes more attractive as the |

|

|

federal funds rate rises. |

|

E |

The equilibrium federal funds rate is established, as usual, at |

|

point E in Figure 1—where the demand and supply curves cross. |

||

|

||

A |

Now suppose the Federal Reserve wants to push the federal |

|

|

funds rate down. It can provide additional reserves to the market |

|

|

by purchasing Treasury bills (often abbreviated as T-bills) from |

|

|

banks.3 This open-market purchase would shift the supply curve of |

|

|

bank reserves outward, from S0S0 to S1S1, in Figure 2. Equilibrium |

Dwould therefore shift from point E to point A, which, as the diagram shows, implies a lower interest rate and more bank reserves. That is precisely what the Fed does when it wants to reduce interest rates.4

The Mechanics of an Open-Market Operation

The bookkeeping behind such an open-market purchase is illustrated by Table 1, which imagines that the Fed purchases $100 million worth of T-bills from commercial banks. When the Fed buys the securities, the ownership of the T-bills shifts from the banks to the Fed—as indicated by the black arrows in Table 1. Next, the Fed makes payment by giving the banks $100 million in new reserves, that is, by adding $100 million to the bookkeeping entries that represent the banks’ accounts at the Fed—called “bank reserves” in the table. These reserves, shown in blue in the table, are liabilities of the Fed and assets of the banks.

You may be wondering where the Fed gets the money to pay for the securities. It could pay in cash, but it normally does not. Instead, it manufactures the funds out of thin air or, more literally, by punching a keyboard. Specifically, the Fed pays the banks by adding the appropriate sums to the reserve accounts that the banks maintain at the Fed. Balances held in these accounts constitute bank reserves, just like cash in bank vaults. Although this process of adding to bookkeeping entries at the Federal Reserve is sometimes referred to as “printing money,” the Fed does not literally run any printing presses. Instead, it simply

3It is not important that banks be the buyers. Test Yourself Question 3 at the end of the chapter shows that the effect on bank reserves and the money supply is the same if bank customers purchase the securities.

4There are many interest rates in the economy, but they all tend to move up and down together. So, in a first course in economics, we need not distinguish one interest rate from another.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.