Color Atlas of Neurology

.pdf

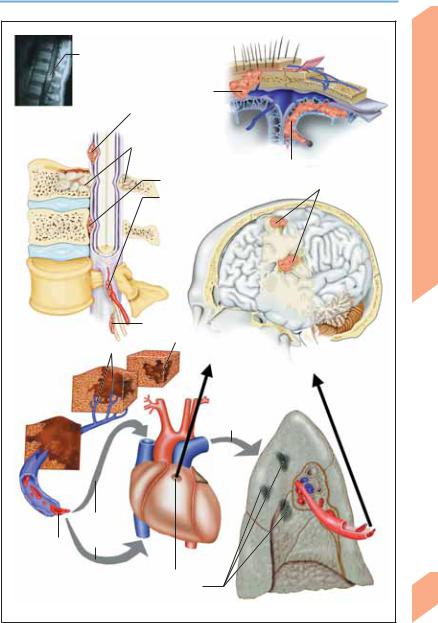

Metastases

Spinal metastasis from bronchial carcinoma

|

|

Cranial metastasis |

|

|

|

MRI (contrast- |

|

Intradural/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

enhanced, sagittal |

|

leptomeningeal |

|

|

|

T1-weighted image |

|

metastasis |

|

|

|

of thoracic spine) |

|

Vertebral body metastasis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

causing secondary spinal cord |

Leptomeningeal metastasis |

||

|

|

compression |

|||

|

|

Epidural metastasis |

|

|

Cerebral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Metastatic |

|

metastases |

|

|

|

compression of vessel |

|

|

|

|

|

(radicular a.) |

|

|

|

|

|

Radicular |

|

|

||||

Spinal metastases |

metastasis |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

Development of |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Malignant cells |

|

|

|

neoplasm distant from CNS |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

infiltrating veins and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

lymph vessels |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Systemic spread of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

malignant cells |

|

Systemic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(via foramen ovale) |

|

spread of |

|

|

|

|

Invasion of lung |

malignant |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

cells |

|||

|

|

|

|

via pulmonary a. |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Invasion of |

|

right heart |

|

by malignant |

Malignant cells |

cells |

Patent foramen ovale

Pulmonary metastases

Pathogenesis of cerebral metastasis

Central Nervous System

263

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

Classification and Treatment

|

As the treatment and prognosis of brain tumors |

|||

|

depend on their histological type and degree of |

|||

|

malignancy, the first step of management is |

|||

|

tissue diagnosis (see Table 31, p. 377). The sub- |

|||

|

sequent clinical course may differ from that pre- |

|||

|

dicted by the histological grade because of |

|||

|

“sampling error” (i.e., biopsy of an unrepresen- |

|||

|

tative portion of the tumor). Other factors in- |

|||

|

fluencing prognosis include age, the complete- |

|||

System |

ness of surgical resection, the preoperative and |

|||

postoperative neurological findings, tumor pro- |

||||

gression, and the site of the tumor. |

||||

|

||||

Nervous |

! Incidence (adapted from Lantos et al., 1997) |

|||

The most common primary intracranial tumors |

||||

in patients under 20 years of age are medullo- |

||||

blastoma, pilocytic astrocytoma, ependymoma, |

||||

Central |

and astrocytoma (WHO grade II); from age 20 to |

|||

age 45, astrocytoma (WHO grade II), oligoden- |

||||

|

||||

|

droglioma, acoustic |

neuroma |

(schwannoma), |

|

|

and ependymoma; over age 45, glioblastoma, |

|||

|

meningioma, acoustic neuroma, and oligoden- |

|||

|

droglioma. The overall incidence of pituitary |

|||

|

tumors (including |

pituitary |

metastases), |

|

craniopharyngioma, and intracranial lymphoma and sarcoma is low.

! Severity (Table 32, p. 378)

The Karnofsky scale (Karnofsky et al., 1951) is a commonly used measure of neurological disability, e. g., due to a brain tumor. Its use permits a standardized assessment of clinical course.

! Treatment

The initial treatment is often neurosurgical, with the objective of removing the tumor as completely as possible without causing a severe or permanent neurological deficit. The resection can often be no more than subtotal because of the proximity of the tumor to eloquent brain areas or the lack of a distinct boundary between the tumor and the surrounding tissue. The overall treatment plan is usually a combination of different treatment modalities, chosen with consideration of the patient’s general condition and the location, extent, and degree of malignity

264of the tumor.

Symptomatic treatment. Edema: The an-

tiedematous action of glucocorticosteroids

takes effect several hours after they are administered; thus, acute intracranial hypertension must be treated with an intravenously given osmotic agent (20% mannitol). Glycerol can be given orally to lower the corticosteroid dose in chronic therapy. Antiepileptic drugs (e. g., phenytoin or carbamazepine) are indicated if the patient has already had one or more seizures, or else prophylactically in patients with rapidly growing tumors and in the acute postoperative setting. Pain often requires treatment (headache, painful neoplastic meningeosis, painful local tumor invasion; cf. WHO staged treatment scheme for cancer-related pain). Restlessness: treatment of cerebral edema, psychotropic drugs (levomepromazine, melperone, chlorprothixene). Antithrombotic prophylaxis: Subcutaneous heparin.

Grade I tumors. Some benign tumors, such as those discovered incidentally, can simply be ob- served—for example, with MRI scans repeated every 6 months—but most should be surgically resected, as a total resection is usually curative. Residual tumor after surgery can often be treated radiosurgically (if indicated by the histological diagnosis). Pituitary tumors and craniopharyngiomas can cause endocrine disturbances. Meningiomas and craniopharyngiomas rarely recur after (total) resection.

Grade II tumors. Five-year survival rate is 50–80%. Complete surgical resection of grade II tumors can be curative. As these tumors grow slowly, they are often less aggressively resected than malignant tumors, so as not to produce a neurological deficit (partial resection, later resection of regrown tumor if necessary). Observation with serial MRI rather than surgical resection may be an appropriate option in some patients after the diagnosis has been established by stereotactic biopsy; surgery and/or radiotherapy will be needed later in case of clinical or radiological progression. Chemotherapy is indicated for unresectable (or no longer resectable) tumors, or after failure of radiotherapy

Grade III tumors. Patients with grade III tumors survive a median of 2 years from the time of diagnosis with the best current treatment involving multiple modalities (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy). Many patients, however, live considerably longer. There are still inadequate

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Brain Tumors

data on the potential efficacy of chemotherapy against malignant forms of meningioma, plexus papilloma, pineocytoma, schwannoma, hemangiopericytoma, and pituitary adenoma.

Grade IV tumors. Patients with grade IV tumors survive a median of ca. 10 months from diagnosis even with the best current multimodality treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy). The 5-year survival rate of patients with glioblastoma is no more than 5%. PNET (including medulloblastoma) and primary cerebral lymphoma have median survival times of a few years.

Cerebral metastases: Solitary, surgically accessible metastases are resected as long as there is no acute progression of the underlying malignant disease, or for tissue diagnosis if the primary tumor is of unknown type. Solitary metastases of diameter less than 3 cm can also be treated with local radiotherapy, in one of two forms: interstitial radiotherapy with surgically implanted radioactive material (brachytherapy), or stereotactic radiosurgery. The latter is a closed technique, requiring no incision, employing multiple radioactive cobalt sources (as in the Gamma Knife and X-Knife) or a linear accelerator. Solitary or multiple brain metastases in the setting of progressive primary disease are generally treated with whole-brain irradiation. Chemotherapy is indicated for tumors of known

responsiveness to chemotherapy in patients whose general condition is satisfactory. Metastatic small-cell lung cancer, primary CNS lymphoma, and germ cell tumors are treated with radiotherapy or chemotherapy rather than surgery.

Spinal metastases: Resection and radiotherapy for localized tumors; radiotherapy alone for diffuse metastatic disease.

Leptomeningeal metastases: Chemotherapy (systemic, intrathecal, or intraventricular); irradiation of neuraxis.

! Aftercare

Follow-up examinations are scheduled at shorter or longer intervals depending on the degree of malignity of the neoplasm and on the outcome of initial management (usually involving some combination of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), with adjustment for individual factors and for any complications that may be encountered in the further course of the disease. A single CT or MRI scan 3 months postoperatively may suffice for the patient with a completely resected, benign tumor, while patients with malignant tumors should be followed up by examination every 6 weeks and neuroimaging every 3 months, at least initially. Later visits can be less frequent if the tumor does not recur.

Central Nervous System

265

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Trauma

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

The outcome of traumatic brain injury depends on the type and extent of the acute (primary) injury and its secondary and late sequelae.

Direct/indirect history. A history of the precipitating event and of the patient’s condition at the scene should be obtained from the patient (if possible), or from an eyewitness, or both. Vomiting or an epileptic seizure in the acute aftermath of the event should be noted. Also important are the past medical history, current medications (particularly anticoagulants), and any history of alcoholism or drug abuse.

Physical examination. General: Open wounds, fractures, bruises, bleeding or clear discharge from the nose or ear. Neurological: Respiration, circulation, pupils, motor function, other focal signs.

Diagnostic studies. Laboratory: Blood count, coagulation, electrolytes, blood glucose, urea, creatinine, serum osmolality, blood alcohol, drug levels in urine, pregnancy testing if indicated.

Essential radiological studies: Head CT with brain and bone windows is mandatory in all cases un-

less the neurological examination is completely normal. A cervical spine series from C1 to C7 is needed to rule out associated cervical injury. Plain films of the skull are generally unnecessary if CT is performed.

Additional studies, as indicated: Cranial or spinal MRI or MR angiography, EEG, Doppler ultrasonography, evoked potentials.

In multiorgan trauma: Blood should be typed and cross-matched and several units should be kept ready for transfusion as needed. Physical examination and ancillary studies for any fractures, abdominal bleeding, pulmonary injury.

! Primary Injury

The primary injury affects different parts of the skull and brain depending on the precipitating event. The traumatic lesion may be focal (hematoma, contusion, infarct, localized edema) or diffuse (hypoxic injury, subarachnoid hemorrhage, generalized edema). The worse the injury, the more severe the impairment of consciousness (pp. 116 ff). The clinical assessment of impairment of consciousness is described on pp. 378 f (Tables 33 and 34).

Region |

Type of Injury |

|

|

|

|

Scalp |

Cephalhematoma (neonates), laceration, scalping injury |

|

Skull |

" Fracture mechanism: Bending fracture (caused by blows to the head, etc.), burst frac- |

|

|

|

ture (caused by broad skull compression) |

|

" Fracture type: Linear fracture (fissure, fissured fracture, separation of cranial sutures), |

|

|

|

impression fracture, fracture with multiple fragments, puncture fracture, growing |

|

|

skull fracture (in children only) |

|

" Fracture site: Convexity (calvaria), base of skull |

|

|

" Basilar skull fracture: Frontobasal (bilateral periorbital hematoma (“raccoon sign”), |

|

|

|

bleeding from nose/mouth, CSF rhinorrhea) or laterobasal (hearing loss, eardrum le- |

|

|

sion, bleeding from the ear canal, CSF otorrhea, facial nerve palsy) |

|

" Facial skull fracture: LeFort I–III midface fracture; orbital base fracture |

|

Dura mater |

Open head trauma1, CSF leak, pneumocephalus, pneumatocele |

|

Blood vessels |

Acute epidural, subdural, subarachnoid or intraparenchymal hemorrhage; carotid– |

|

|

cavernous sinus fistula; arterial dissection |

|

Brain2 |

" |

Contusion |

|

" Diffuse axonal injury (clinical features: coma, autonomic dysfunction, decortication |

|

|

|

or decerebration, no focal lesion on CT or MRI) |

|

" Penetrating (open or closed3) injury, or perforating (open) injury |

|

|

" |

Brainstem injury |

|

|

|

1 Wound with open dura and exposure of brain (definition). 2 Excluding cranial nerve lesions. 3 Without dural penetration (definition).

266

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Trauma

|

|

|

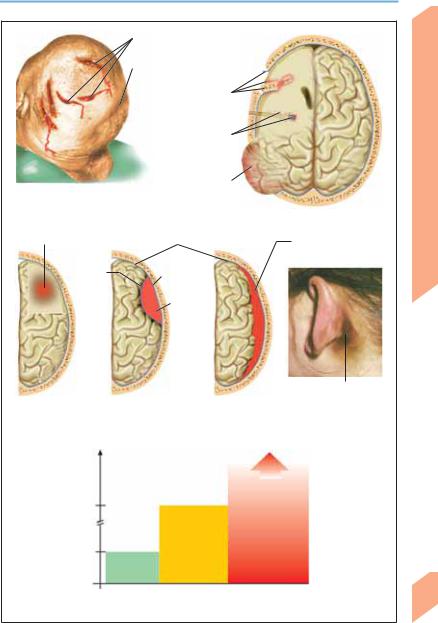

Lacerations |

||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Cranial impression |

||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Depressed skull |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

fracture, hematoma, |

||||

|

|

|

dural opening |

||||

|

|

|

Gunshot |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

wound, hema- |

||||

|

|

|

toma along |

||||

|

|

|

trajectory |

||||

|

|

|

Brain herniation, |

|

|

||

|

|

||||||

Head injuries |

|

|

edema |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hemorrhagic contusion |

|

Inner and outer dural layer |

|||||

Inner |

|

|

Outer |

||||

dural layer |

|

|

|||||

|

|

dural layer |

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Epidural |

||||

|

|

|

hematoma |

||||

Traumatic intracranial hematoma |

|

(Duration of |

|

unconsciousness) |

Moderate |

|

|

24 h |

HT |

|

|

|

GCS: |

Mild HT |

9-12 |

1 h |

|

GCS: |

|

13-15 |

|

Head trauma (schematic)

Subdural hematoma

Retroauricular ecchymosis (due to basilar skull fracture)

Severe

HT

GCS: 3-8

Classification of head trauma (HT) by Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

Central Nervous System

267

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

268

Trauma

! Secondary Sequelae of TBI

Type of Sequela |

Location/Syndrome |

Special Features |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Neurological |

|

|

|

|

|

" |

Hematoma |

Epidural |

Lucid interval1, immediate uncon- |

||

|

|

|

|

sciousness, or progressive deterioration of |

|

|

|

|

|

consciousness |

|

|

|

Subdural |

May be asymptomatic at first, with |

||

|

|

|

|

progressive decline of consciousness |

|

|

|

Subarachnoid |

Meningism |

||

|

|

Intraparenchymal |

Intracranial hypertension, focal signs; |

||

|

|

|

|

often a severe injury |

|

" |

Intracranial |

" |

Cerebral edema, hydrocephalus, |

" |

See p. 162. Risk of herniation |

|

hypertension |

|

massive hematoma |

|

|

" |

Ischemia |

" Vasospasm, arterial dissection, fat |

" |

Acute focal signs |

|

|

|

|

embolism |

|

|

" |

Epileptic seizure |

" |

Focal or generalized |

" Common in focal injury |

|

" |

Infection |

" |

CSF leak, open head injury |

" |

Recurrent meningitis, encephalitis, |

|

|

|

|

|

empyema, abscess, ventriculitis |

" |

Amnesia |

" |

Anterograde/retrograde |

" |

See p. 134 |

General |

|

|

|

|

|

" |

Hypotension, |

" |

Shock, respiratory failure |

" Multiple trauma, pneumothorax or |

|

|

hypoxia, anemia |

|

|

|

hemothorax, pericardial tamponade, |

|

|

|

|

|

blood loss, coagulopathy |

" |

Fever, |

" |

Infection |

" |

Pneumonia, sepsis, CSF leak |

|

meningitis |

|

|

|

|

" |

Fluid imbalance |

" |

Hypothalamic lesion |

" |

Diabetes insipidus2, SIADH3 |

1 Patient immediately loses consciousness awakens and appears normal for a few hours again loses consciousness. 2 Polyuria, polydipsia, nocturia, serum osmolality !295 mOsm/kg, urine osmolality. 3 Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of ADH: euvolemia, serum osmolality " 275 mOsm/kg, excessively concentrated urine (urine osmolality !100 mOsm/kg), urinary sodium despite normal salt/water intake; absence of adrenal, thyroid, pituitary and renal dysfunction.

For overview of late complications of head trauma, see p. 379 (Table 35).

! Prognosis

Head trauma causes physical impairment and behavioral abnormalities whose severity is correlated with that of the initial injury.

Severity1 |

Prognosis |

|

|

Mild |

Posttraumatic syndrome resolves within 1 year in 85–90% of patients. The re- |

|

maining 10–15% develop a chronic posttraumatic syndrome |

Moderate |

The symptoms and signs resolve more slowly and less completely than those of |

|

mild head injury. The prognosis appears to be worse for focal than for diffuse in- |

|

juries. Reliable data on the long-term prognosis are not available |

Severe |

Age-dependent mortality ranges from 30% to 80%. Younger patients have a bet- |

|

ter prognosis than older patients. Late behavioral changes (impairment of |

|

memory and concentration, abnormal affect, personality changes) |

|

|

1 For severity of head trauma, cf. pp. 378 f, Tables 33 and 34.

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Trauma

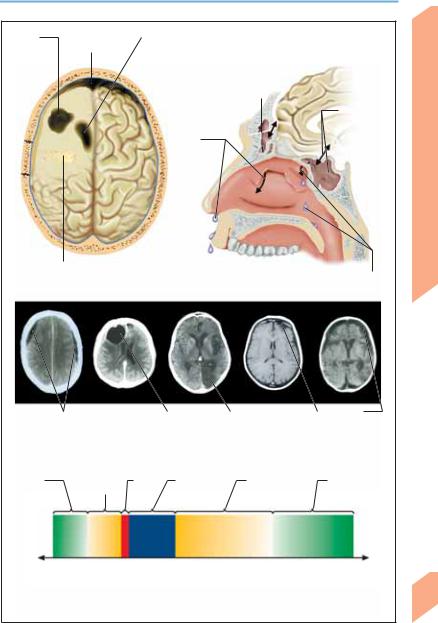

Cystic |

Frontal brain |

|

Brain atrophy, normal pressure hydrocephalus |

|

||

|

|

|||||

postcon- |

atrophy |

|

(ventricular dilatation) |

|

||

tusional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

defect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frontal sinus, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

fracture |

Basilar skull |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

fracture, |

|

|

|

CSF |

sphenoid |

||

|

|

|

sinus |

|||

|

|

|

leak from |

|

||

nose

Infection, abscess (penetrating injury) |

|

|

Cerebral complications of trauma |

|

CSF leak |

CSF leak |

(nasopharyngeal space) |

Bilateral |

|

|

Pneumocephalus |

|

Infarct |

|

|

Postcontu- |

|

Frontal |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

chronic subdural |

(air in intracranial |

(posterior |

sional lesion |

brain atrophy |

||||||

hematoma |

cavity) |

cerebral artery) |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Posttraumatic neurological changes |

|

||||||

Normal |

Retrograde Trauma |

Unconscious- |

Anterograde |

Normalization |

||||||

memory |

amnesia |

ness or coma |

amnesia |

of memory |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

function |

(Time)

Time course of memory disturbances

(closed head injury)

Central Nervous System

269

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

270

Trauma

! Posttraumatic Headache |

Intracerebral |

hematoma. |

Bleeding |

into |

the |

||||

tissue of the brain (intraparenchymal hema- |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

Posttraumatic headache may be acute (!8 |

toma) under the site of impact, on the opposite |

||||||||

weeks after head trauma) or chronic ("8 |

side (contre-coup), or in the ventricular system |

||||||||

weeks). The duration and intensity of the head- |

(intraventricular hemorrhage) (pp. 176, 267). |

||||||||

ache are not correlated with the severity of the |

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Rupture of pial ves- |

||||||||

precipitating head trauma. It can be focal or dif- |

sels. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

fuse, continuous or episodic. It often worsens |

! Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

with physical exertion, mental stress, and ten- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

sion and improves with rest and stress |

At the scene of the accident. The scene should |

||||||||

avoidance. Its type and extent are highly varia- |

be secured to prevent further injury to the in- |

||||||||

ble. If the headache gradually increases in sever- |

jured person, bystanders, or rescuers. First aid: |

||||||||

ity, or if a new neurological deficit arises, further |

Evaluation and clearing of the airway; car- |

||||||||

studies should be performed to exclude a late |

diopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) if necessary. |

||||||||

posttraumatic complication, such as chronic |

Immobilization of the cervical spine with a hard |

||||||||

subdural hematoma (p. 379). |

collar. Recognition and treatment of hemody- |

||||||||

! Pathogenesis of Traumatic Brain Injury |

namic instability (keep systolic blood pressure |

||||||||

above |

120 mmHg), |

fluid |

administration |

as |

|||||

|

|||||||||

Direct blunt or penetrating injuries of the head |

needed (“small volume resuscitation” with hy- |

||||||||

and acceleration/deceleration injuries can dam- |

peroncotic-hypertonic solutions’). Dressing of |

||||||||

age the scalp, skull, meninges, cerebral vascula- |

wounds, sedation if necessary to reduce agita- |

||||||||

ture, ventricular system, and brain parenchyma. |

tion, elevation of the upper body to 30°. Docu- |

||||||||

The term primary injury refers to the initial me- |

mentation: Time and nature of accident, general |

||||||||

chanical damage to these tissues. Traumatized |

and neurological findings, drugs given. Trans- |

||||||||

brain tissue is more sensitive to physiological |

port: Cardiorespiratory monitoring. |

|

|

||||||

changes than nontraumatized tissue. Secondary |

In the hospital. Systematic assessment and |

||||||||

injury is caused by cellular dysfunction due to |

treatment by organ system, with documenta- |

||||||||

focal or global changes in cerebral blood flow and |

tion of all measures taken. Cardiorespiratory |

||||||||

metabolism. Mechanisms involved in secondary |

monitoring: monitoring of blood gases and |

||||||||

injury include disruption of the blood–brain bar- |

blood |

pressure |

(cerebral |

perfusion |

pressure |

||||

rier, hypoxia, neurochemical changes (increased |

"60–70 mmHg, |

p. 162). |

Respiratory |

system: |

|||||

concentrations of acetylcholine, norepinephrine, |

Supplementary oxygen, intubation, and ventila- |

||||||||

dopamine, epinephrine, magnesium, calcium, |

tion as needed. Cardiovascular system: Central |

||||||||

and excitatory amino acids such as glutamate), |

venous access, administration of fluids and |

||||||||

cytotoxic processes (production of free radicals |

pressors as needed. Treatment of fever or hyper- |

||||||||

and of calcium-activated proteases and lipases), |

thermia. Administration of anticonvulsants as |

||||||||

and inflammatory responses (edema, influx of |

needed. Evaluation of tetanus vaccination sta- |

||||||||

leukocytes and macrophages, cytokine release). |

tus. Immediate neurosurgical consultation re- |

||||||||

Epidural hematoma. Bleeding into the epidural |

garding the possible need for surgery. Treatment |

||||||||

space (pp. 6, 267) due to detachment of the |

of intracranial hypertension: Sedatives, analges- |

||||||||

outer dural sheath from the skull and rupture of |

ics; if |

ICP |

(p. 162) |

is above 20–25 mmHg, |

|||||

a meningeal artery (usually the middle mening- |

osmotherapy with 20% mannitol, bolus of |

||||||||

eal artery, torn by a linear fracture of the tem- |

0.35 mg/kg over 10–15 minutes, repeated every |

||||||||

poral bone). Epidural hematoma is less |

4–8 hours as needed; barbiturate coma |

||||||||

frequently of venous origin (usually due to tear- |

(thiopental); |

|

decompressive |

bifrontal |

|||||

ing of a venous sinus by a skull fracture). |

craniectomy may be indicated in refractory |

||||||||

Subdural hematoma. Bleeding into the subdural |

cerebral edema. |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

space (pp. 6, 176, 267) because of disruption of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

larger bridging veins; often accompanied by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

focal contusion of the underlying brain. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frequently located in the temporal region. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Trauma

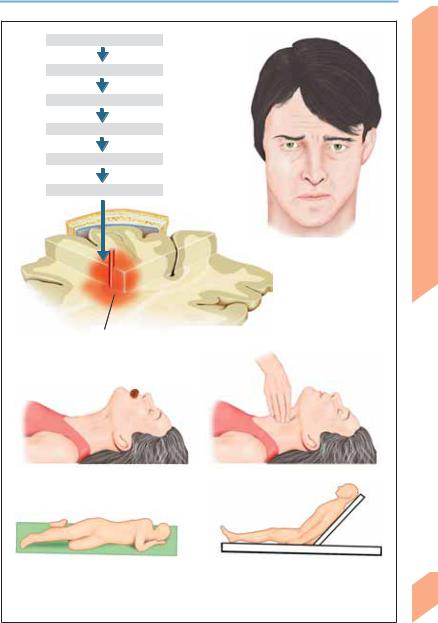

Traumatic brain injury

Blood-brain barrier lesion

Hypoxia

Neurochemical changes

Cytotoxic processes

Inflammatory response

Posttraumatic headache

Hemorrhagic contusion

Pathogenesis of traumatic brain injury

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ensure that airways are free and unobstructed |

|

|

|

|

Check cardiopulmonary function |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stable lateral position: Patient is |

Supine position: Patient is unconscious, not |

||

unconscious but breathing spontaneously |

|

breathing (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), |

|

|

|

and may have spinal injury. Elevate upper |

|

|

|

body if there is a head injury |

|

First-aid measures at scene of accident

Central Nervous System

271

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Central Nervous System

Trauma

Spinal Trauma

Spinal injury can involve the vertebrae, ligaments, intervertebral disks, blood vessels, muscles, nerve roots, and spinal cord. The spinal cord and spinal nerve roots may be directly injured (e. g. by gunshot or stab wounds) or secondarily affected by compression (bone fragments), hyperextension (spinal instability), and vascular lesions (ischemia, hemorrhage). Diagnosis: Bone injuries can be identified by radiography and/or CT; spinal cord lesions (hemorrhage, contusion, edema, transection) and softtissue lesions (hematoma, edema, arterial dissection) are best seen on MRI.

Cervical spine distortion (whiplash injury). Indirect spinal trauma (head-on or rear-end collision) leads to sudden passive retroflexion and subsequent anteflexion of the neck. The forces acting on the spine (acceleration, deceleration, rotation, traction) can produce both cervical spine injuries (spinal cord, nerve roots, retropharyngeal space, bones, ligaments, joints, intervertebral disks, blood vessels) and cranial injuries (brain, eyes, temporomandibular joint). There may be an interval of 4–48 hours until symptoms develop, rarely longer (asymptomatic period). Symptoms and signs: Pain in the head, neck, and shoulders, neck stiffness, and vertigo may be accompanied by forgetfulness, poor concentration, insomnia, and lethargy. The symptoms usually resolve within 3–12 months but persist for longer periods in 15–20% of patients, for unknown reasons. Severity classification: Grade I = no neurological deficit or radiological abnormality, grade II = neurological deficit without radiological abnormality, grade III = neurological deficit and radiological abnormality.

bral disks as composed of three columns. Involvement of only one column = stable injury; two columns = potentially unstable; three columns = unstable. For details, see p. 380 (Table 36).

Trauma to nerve roots and brachial plexus.

Nerve root lesions usually involve the ventral roots, and thus usually produce a motor rather than sensory deficit. Nerve root avulsion may be suspected on the basis of (multi)radicular findings and/or Horner syndrome and can be confirmed by myelography (empty root sleeves, bulging of the subarachnoid space) or MRI. Downward or backward traction on the shoulder and arm (as in a motorcycle accident) can produce severe brachial plexus injuries accompanied by nerve root avulsion. Brachial plexus lesions can also be caused by improper patient positioning during general anesthesia, intense supraclavicular pressure (backpack paralysis), or local trauma (stab or gunshot wound, bone fragments, contusion, avulsion). These injuries more commonly affect the upper portion of the brachial plexus (pp. 34, 321).

Vertebral fracture. It must be determined whether the fracture is stable or unstable; if it is unstable, any movement can cause (further) damage to the spinal cord and nerve roots. Thus, all patients who may have vertebral fractures must be transported in a stabilized supine position, with the head in a neutral position (e. g., on a vacuum mattress). Repositioning the patient manually with the “collar splint grip,” “paddle

272grip,” or “bridge grip” should be avoided if possible. In the assessment of stability, it is useful to consider the spinal column and interverte-

Rohkamm, Color Atlas of Neurology © 2004 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.