R.Daft Understanding Management

.pdf

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

20 Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World

Managing in Small Businesses and

Nonprofit Organizations

Small businesses are growing in importance. Hundreds of small businesses are opened every month, but the environment for small business today is highly complicated. Experts believe entrepreneurial ventures are crucial to global economic recovery, yet small companies can be particularly vulnerable in a turbulent environment. Small companies sometimes have difficulty developing the managerial dexterity to survive when conditions turn chaotic. Appendix A provides detailed information about managing in small businesses and entrepreneurial start-ups.

One interesting finding is that managers in small businesses tend to emphasize roles different from those of managers in large corporations. Managers in small companies often see their most important role as that of spokesperson because they must promote the small, growing company to the outside world. The entrepreneur role is also critical in small businesses because managers have to be innovative and help their organizations develop new ideas to remain competitive. Small-business managers tend to rate lower on the leader role and on information-processing roles compared with their counterparts in large corporations.

Nonprofit organizations also represent a major application of management talent. Organizations such as the Salvation Army, Nature Conservancy, Greater Chicago Food Depository, Girl Scouts, and Cleveland Orchestra all require excellent management. The functions of planning, organizing, leading, and controlling apply to nonprofits just as they do to business organizations, and managers in nonprofit organizations use similar skills and perform similar activities.The primary difference is that managers in businesses direct their activities toward earning money for the company, whereas managers in nonprofits direct their efforts toward generating some kind of social impact. The characteristics and needs of nonprofit organizations created by this distinction present unique challenges for managers.27

Financial resources for nonprofit organizations typically come from government appropriations, grants, and donations rather than from the sale of products or services to customers. In businesses, managers focus on improving the organization’s products and services to increase sales revenues. In nonprofits, however, services are typically provided to nonpaying clients, and a major problem for many organizations is securing a steady stream of funds to continue operating. Nonprofit managers, committed to serving clients with limited resources, must focus on keeping organizational costs as low as possible.28 Donors generally want their money to go directly to helping clients rather than for overhead costs. If nonprofit managers can’t demonstrate a highly efficient use of resources, they might have a hard time securing additional donations or government appropriations. Although the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (the 2002 corporate governance reform law) doesn’t apply to nonprofits, many are adopting its guidelines, striving for greater transparency and accountability, to boost credibility with constituents and be more competitive when seeking funding.29

In addition, because nonprofit organizations do not have a conventional bottom line, managers often struggle with the question of what constitutes results and effectiveness. It is easy to measure dollars and cents, but the metrics of success in nonprofits are much more ambiguous. Managers have to measure intangibles such as “improved public health,” “a difference in the lives of the disenfranchised,” or “increased appreciation for the arts.” This intangible nature also makes it more difficult to gauge the performance of employees and managers. An added complication is that managers often depend on volunteers and donors who cannot be supervised and controlled in the same way a business manager deals with employees. Many people who move from the corporate world to a nonprofit are surprised to find that the work hours are often longer and the stress greater than in their previous management jobs.30

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

Innovative Management for the New Workplace |

21 |

The roles defined by Mintzberg also apply to nonprofit managers, but these may differ somewhat. We might expect managers in nonprofit organizations to place more emphasis on the roles of spokesperson (to “sell” the organization to donors and the public), leader (to build a mission-driven community of employees and volunteers), and resource allocator (to distribute government resources or grant funds that are often assigned top-down).

Managers in all organizations—large corporations, small businesses, and nonprofit organizations—carefully integrate and adjust the management functions and roles to meet challenges within their own circumstances and keep their organizations healthy.

•Good management is just as important for small businesses and nonprofit organizations as it is for large corporations.

•Managers in these organizations adjust and integrate the various management functions, activities, and roles to meet the unique challenges they face.

•Managers in small businesses often see their most important roles as being a

spokesperson for the business and acting as an entrepreneur.

•Managers in nonprofit organizations direct their efforts toward generating some kind of social impact rather than toward making money for the organization.

•Nonprofit organizations don’t have a conventional bottom line, so managers often struggle with what constitutes effectiveness.

Innovative Management for the New Workplace

In recent years, the central theme being discussed in the field of management has been the pervasiveness of dramatic change in the workplace. Rapid environmental shifts are causing fundamental transformations that have a dramatic impact on the manager’s job. These transformations are reflected in the transition to a new workplace, as illustrated in Exhibit 1.5.

Turbulent Forces

Dramatic advances in technology, globalization, shifting social values, changes in the workforce, and other environmental shifts have created a challenging environment for organizations. Perhaps the most pervasive change affecting organizations and management is technology. The Internet and electronic communication have transformed the way business is done and the way managers perform their jobs. Many organizations use digital technology to tie together employees and partners located worldwide. With new technology, it’s easy for people to do their jobs from home or other locations outside company walls. In addition, many companies are shifting more and more chunks of what were once considered core functions to outside organizations via outsourcing, which requires coordination across organizations.

The pace of life for most people and organizations is high speed. People can work around the clock. Ideas, documents, music, personal information, and all types of data are constantly being zapped through cyberspace, and events in one part of the world can dramatically influence business all over the globe. In general, events in today’s world are turbulent and unpredictable, with both small and large crises occurring on a more frequent basis.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

22 Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World

1.5 |

|

EXHIBIT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Transition to a New Workplace |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Managing the |

Managing the |

|

|

|

New Workplace |

Old Workplace |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forces |

|

|

|

|

Technology |

Digital |

Mechanical |

|

|

Focus |

Global |

Local, domestic markets |

|

|

Workforce |

Diverse |

Homogenous |

|

|

Pace |

Change, speed |

Stability, efficiency |

|

|

Events |

Turbulent, frequent crises |

Calm, predictable |

|

|

Characteristics |

|

|

|

|

Resources |

Information, knowledge |

Physical assets |

|

|

Work |

Flexible, virtual |

Structured, localized |

|

|

Workforce |

Empowered employees |

Loyal employees |

|

|

Management Competencies |

|

|

|

|

Leadership |

Dispersed, empowering |

Autocratic |

|

|

Doing Work |

By teams |

By individuals |

|

|

Relationships |

Collaboration |

Conflict, competition |

|

|

Design |

Experimentation, learning |

Top-down control |

New Workplace Characteristics31

© Cengage Learning 2013

The old workplace was characterized by routine, specialized tasks, and standardized control procedures. Employees typically performed their jobs in one specific company facility, such as an automobile factory located in Detroit or an insurance agency located in Des Moines. Individuals concentrated on doing their own specific tasks, and managers were cautious about sharing knowledge and information across boundaries. The organization was coordinated and controlled through the vertical hierarchy, with decision-making authority residing with upper-level managers.

In the new workplace, by contrast, work is free flowing and flexible. Structures are flatter, and lower-level employees are empowered to make decisions based on widespread information and guided by the organization’s mission and values.32 Knowledge is widely shared, and people throughout the company keep in touch with a broad range of colleagues via advanced technology. The valued worker is one who learns quickly, shares knowledge, and is comfortable with risk, change, and ambiguity. People expect to work on a variety of projects and jobs throughout their careers rather than staying in one field or with one company.

In the new workplace, work is often virtual, with managers having to supervise and coordinate people who never actually “come to work” in the traditional sense.33 Flexible hours, telecommuting, and virtual teams are increasingly popular ways of working that require new skills from managers. Teams may include outside contractors, suppliers, customers, competitors, and interim managers. Interim managers, or contingent managers, are managers who are not affiliated with a specific organization but work on a project-by-project basis or temporarily provide expertise to organizations in a specific area.34 This approach enables

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

Innovative Management for the New Workplace |

23 |

a company to benefit from specialist skills without making a long-term commitment, and it provides flexibility for managers who like the challenge, variety, and learning that come from working in a wide range of organizations. One estimate is that the market for contingent managers will grow 90 percent over the next decade.35

New Management Competencies

In the face of these transitions, managers rethink their approach to organizing, directing, and motivating employees. Instead of “management by keeping tabs,” managers employ an empowering leadership style. When people are working at scattered locations, managers can’t continually monitor behavior. In addition, they are sometimes coordinating the work of people who aren’t under their direct control, such as those in partner organizations.

Success in the new workplace depends on collaboration across functions and hier-

archical levels as well as with customers and other companies. Experimentation and learning are key values, and managers encourage people to share information and knowledge.

The shift to a new way of managing isn’t easy for traditional managers who are accustomed to being “in charge,” making all the decisions, and knowing where their subordinates are and what they’re doing at every moment. Even many new managers have a hard time with today’s flexible work environment. For example, managers of departments participating in Best Buy’s Results-Only Work Environment program, which allows employees to work anywhere, anytime, as long as they complete assignments and meet goals, find it difficult to keep themselves from checking to see who’s logged on to the company network.36

Even more changes and challenges are on the horizon for organizations and managers. This is an exciting and challenging time to be entering the field of management. Throughout this book, you will learn much more about the new workplace, about the new and dynamic roles managers are playing in the twenty-first century, and about how you can be an effective manager in a complex, ever-changing world.

Read the Ethical Dilemma, on page 45, that pertains to managing in the new

workplace. Think about what you would do and why, to begin understanding how you will solve thorny management problems.

•Turbulent environmental forces have caused significant shifts in the workplace and the manager’s job.

•In the old workplace, a manager’s competency could include a command-and- control leadership style, and managers could focus on individual tasks and on standardizing procedures.

•In the new workplace, a manager’s competency should include an empowering

leadership style, and managers should focus on developing teamwork, collaboration, and learning.

•The new workplace often employs interim managers, managers who are not affiliated with any particular organization but work on a project- by-project basis or provide expertise to an organization in a specific

area.

©image100/Corbis

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

24 Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World

Innovative Management Thinking for a

Changing World

All of the ideas and approaches discussed so far in this chapter go into the mix that makes up modern management. Dozens of ideas and techniques in current use can trace their roots to these historical perspectives.37 In addition, innovative concepts continue to emerge to address management challenges in today’s turbulent world.

Contemporary Management Tools

SELCO Solar Light Pvt. Ltd.

Managers tend to look for fresh ideas to help them cope during difficult times. For instance, consider that in 2002, surveys noted a dramatic increase in the variety of techniques and ideas managers were trying, reflecting the turbulence of the environment following the crash of the dot-coms, the 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, and a series of corporate scandals such as Enron.38 Similarly, recent challenges such as the tough economy and volatile stock market, environmental and organizational crises, lingering anxieties over war and terrorism, and public suspicion and skepticism resulting from the crisis on Wall Street have left today’s executives searching for any management tool—new or old—that can help them get the most out of limited resources. The Spotlight on Skills titled Contemporary Management Tools lists a wide variety of ideas and techniques used by today’s managers. Management idea life cycles have been growing shorter as the pace of change has increased. A study by professors at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette found that from the 1950s to the 1970s, it typically took more than a decade for interest in a popular management idea to peak.

Now, the interval has shrunk to fewer than three years, and some trends come and go even faster.39

ConceptConnection

Energy engineer Harish Hande of his native India, there were silk workers who labored by kerosene lamp even though the fuel could potentially kill the worms. And there were rose pickers and midwives who needed a light source that left their hands free. To meet such needs, Hande used a jugaad mind-set and developed sustainable, affordable, solar-powered lighting systems for domestic and commercial use. Bangalore-based Selco Solar, the company Hande founded, has sold, installed, and serviced well over 100,000 modular solar systems since 1995. Says Hande, “If our product caters to a client’s need, there’s no way he won’t buy it.”

Managing the Technology-Driven Workplace

Three popular recent trends that have shown some staying power, as reflected in the Spotlight on Skills titled Contemporary Management Tools, are customer relationship management, outsourcing, and supply chain management. These techniques are related to the shift to a technology-driven workplace. Today, many employees perform much of their work on computers and may work in virtual teams, connected electronically to colleagues around the world. Even in factories that produce physical goods, machines have taken over much of the routine and uniform work,freeing workers to use more of their minds and abilities. Moreover, companies are using technology to keep in touch with customers and collaborate with other organizations on an unprecedented scale.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

Innovative Management Thinking for a Changing World |

25 |

Spotlight ON SKILLS

Contemporary Management Tools

© Bata Zivanovic, Shutterstock

ver the history of management, many fash- O ions and fads have appeared. Critics argue that new techniques may not represent permanent solutions. Others feel that managers

adopt new techniques for continuous improvement in a fast-changing world.

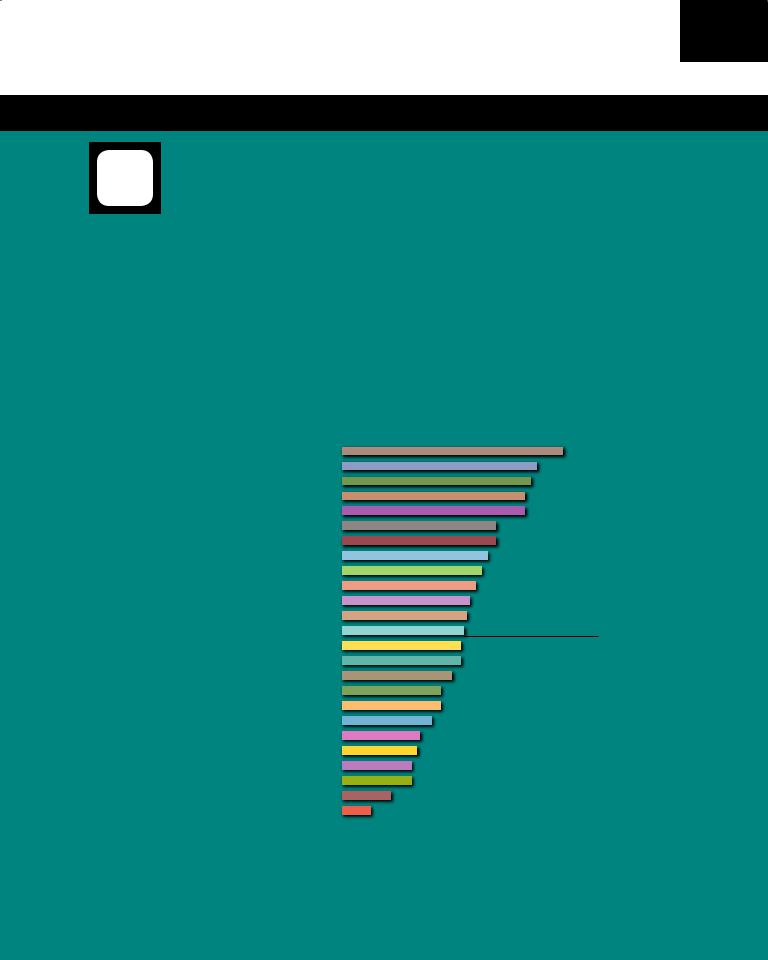

In 1993, Bain and Company started a large research project to interview and survey thousands of corporate executives about the 25 most popular management tools and techniques. The list for 2009 and their usage rates are below. How many tools do you know? For more information on specific tools, visit the Bain website: www.bain

.com/management_tools/home.asp.

Fashion. In the 2009 survey, benchmarking became the most popular tool for the first time in more than a decade, reflecting managers’ concern with efficiency and cost cutting in a difficult economy. Three tools that ranked high in

both use and satisfaction were strategic planning, customer segmentation, and mission and vision statements, tools that can guide managers thinking on strategic issues during times of rapid change.

Global. North American executives were using cost-cutting tools, especially downsizing, more than were managers in other parts of the world in 2008–2009. Latin American companies were the heaviest users of outsourcing. In the Asia-Pacific region, Chinese companies report the greatest use of benchmarking, strategic planning, supply chain management, and total quality management, whereas companies in India are more satisfied with strategic alliances and collaborative innovation than are other Asia-Pacific executives.

SOUrcE: Darrell Rigby and Barbara Bilodeau, “Management Tools and Trends 2009,” Copyright © 2009, Bain and Company, Inc., http://www.bain.com/management_tools/home.asp. Reprinted by permission.

Benchmarking |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

76% |

|

|

|

||

Strategic Planning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

67% |

|

|

|

|

|

Mission and Vision Statements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

65% |

|

|

|

|

|

Customer Relationship Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

63% |

|

|

|

|

|

Outsourcing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

63% |

|

|

|

|

|

Balanced Scorecard |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

53% |

|

|

|

Signi cantly |

||||

Customer Segmentation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

53% |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

above overall |

||||||

Business Process Reengineering |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50% |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

mean |

|||||

Core Competencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

48% |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Mergers and Acquisitions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

46% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Strategic Alliances |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

44% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Supply Chain Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

43% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scenario and Contingency Planning |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

42% |

|

|

|

|

|

Mean 42% |

||

Knowledge Management |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

41% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shared Service Centers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

41% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Growth Strategy Tools |

|

|

|

|

38% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Total Quality Management |

|

|

|

|

34% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Downsizing |

|

|

|

|

34% |

|

|

|

|

|

Signi cantly |

|||||

Lean Six Sigma |

|

|

|

|

31% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

below overall |

||||||

Voice of the Customer Innovation |

|

|

|

|

27% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

mean |

||||

Online Communities |

|

|

|

|

26% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Collaborative Innovation |

|

|

|

|

24% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price Optimization Models |

|

|

|

|

24% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loyalty Management Tools |

|

17% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Decision Rights Tools |

|

10% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

20 |

40 |

60 |

80 |

100 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Usage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

26 |

Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World |

Customer Relationship Management One of today’s most popular applications of technology is for customer relationship management. Customer relationship management (CRM) systems use the latest information technology to keep in close touch with customers and to collect and manage large amounts of customer data. These data can help employees and managers act on customer insights, make better decisions, and provide superior customer service.

There has been an explosion of interest in CRM. In the Spotlight on Skills titled Contemporary Management Tools, 63 percent of surveyed managers reported their companies used CRM in 2008, whereas only 35 percent of companies reported using this technique in 2000. Meeting customer needs and desires is a primary goal for organizations, and using CRM to give customers what they really want provides a tremendous boost to customer service and satisfaction.

Outsourcing Information technology has also contributed to the rapid growth of outsourcing, which means contracting out selected functions or activities to other organizations that can do the work more cost efficiently.The Bain survey indicates that the use of outsourcing increased as the economy declined.Outsourcing requires that managers not only be technologically savvy but that they learn to manage a complex web of relationships. These relationships might reach far beyond the boundaries of the physical organization; they are built through flexible e-links between a company and its employees, suppliers, partners, and customers.40

•Modern management is a lively mix of ideas and techniques from varied historical perspectives, but new concepts continue to emerge.

•Managers tend to look for innovative ideas and approaches particularly during turbulent times.

•Many of today’s popular techniques are related to the transition to a technologydriven workplace.

•Customer relationship management systems use information technology to keep in close touch with customers, collect and manage large amounts of customer data, and provide superior customer value.

•Outsourcing, which means contracting out selected functions or activities to other organizations that can do the work more efficiently, has been one of the fastestgrowing trends in recent years.

The Evolution of Management Thinking

What do managers at U.S.-based companies such as Cisco Systems and Goldman Sachs have in common with managers at India’s Tata Group and Infosys Technologies? One thing is an interest in applying a new concept called jugaad (pronounced “joo-gaardh”). Jugaad perhaps will be a buzzword that quickly fades from managers’ vocabularies, but it could also become as ubiquitous in management circles as terms such as total quality or kaizen. Jugaad basically refers to an innovation mind-set, used widely by Indian companies, that strives to meet customers’ immediate needs quickly and inexpensively. With research and development budgets strained in today’s economy, it’s an approach U.S. managers are picking up on, and the term jugaad has been popping up in seminars, academia, and business consultancies.

Managers are always on the lookout for fresh ideas, innovative management approaches, and new tools and techniques. Management philosophies and organizational forms change over time to meet new needs. The questionnaire at the beginning of this chapter describes two differing philosophies about how people should be managed, and you will learn more about these ideas in this chapter.

If management is always changing, why does history matter to managers? The workplace of today is different from what it was 50 years ago—indeed, from what it was even

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

Management and Organization |

27 |

10 years ago. Yet today’s managers find that some ideas and practices from the past are still highly relevant. For example, certain management practices that seem modern, such as open-book management or employee stock ownership, have actually been around for a long time. These techniques have repeatedly gained and lost popularity since the early twentieth century because of shifting historical forces.41 A historical perspective provides a broader way of thinking, a way of searching for patterns and determining whether they recur across time periods. It is a way of learning from others’ mistakes so as not to repeat them; learning from others’ successes so as to repeat them in the appropriate situation; and most of all, learning to understand why things happen to improve our organizations in the future.

This part of the chapter provides a historical overview of the ideas, theories, and management philosophies that have contributed to making the workplace what it is today. The final section of the chapter looks at some recent trends and current approaches that build on this foundation of management understanding.This foundation illustrates that the value of studying management lies not in learning current facts and research but in developing a perspective that will facilitate the broad, long-term view needed for management success.

Management and Organization

Studying history doesn’t mean merely arranging events in chronological order; it means developing an understanding of the impact of societal forces on organizations. Studying history is a way to achieve strategic thinking, see the big picture, and improve conceptual skills. Let’s begin by examining how social, political, and economic forces have influenced organizations and the practice of management.42

Social forces refer to those aspects of a culture that guide and influence relationships among people. What do people value? What do people need? What are the standards of behavior among people? These forces shape what is known as the social contract, which refers to the unwritten, common rules and perceptions about relationships among people and between employees and management.

One social force is the changing attitudes, ideas, and values of Generation Y employees (sometimes called Millennials).43 These young workers, the most educated generation in the history of the United States, grew up technologically adept and globally conscious. Unlike many workers of the past, they typically are not hesitant to question their superiors and challenge the status quo. They want a work environment that is challenging and supportive, with access to cutting-edge technology, opportunities to learn and further their careers and personal goals, and the power to make substantive decisions and changes in the workplace. In addition, Gen-Y workers have prompted a growing focus on work/life balance, reflected in trends such as telecommuting, flextime, shared jobs, and organization-sponsored sabbaticals.

Political forces refer to the influence of political and legal institutions on people and organizations. One significant political force is the increased role of government in business after the collapse of companies in the financial services sector and major problems in the auto industry. Some managers expect increasing government regulations in the coming years.44 Political forces also include basic assumptions underlying the political system, such as the desirability of self-government, property rights, contract rights, the definition of justice, and the determination of innocence or guilt of a crime.

Economic forces pertain to the availability, production, and distribution of resources in a society. Governments, military agencies, churches, schools, and business organizations in every society require resources to achieve their goals, and economic forces influence the allocation of scarce resources. Companies in every industry have been affected by the recent financial crisis that was the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Reduced consumer spending and tighter access to credit have curtailed growth and left companies scrambling to meet goals with limited resources. Although liquidity for large corporations showed an increase in early 2010, smaller companies continued to struggle to find funding.45

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

28 Chapter 1 Innovative Management for a Changing World

Another economic trend that affects managers worldwide is the growing economic power of countries such as China, India, and Brazil.46

Management practices and perspectives vary in response to these social, political, and economic forces in the larger society. Exhibit 1.6 illustrates the evolution of significant management perspectives over time. The timeline reflects the dominant time period for each approach, but elements of each are still used in today’s organizations.47

•Managers are always on the lookout for new techniques and approaches to meet shifting organizational needs.

•Looking at history gives managers a broader perspective for interpreting and responding to current opportunities and problems.

•Management and organizations are shaped by forces in the larger society.

•Social forces are aspects of a society that guide and influence relationships

among people, such as their values, needs, and standards of behavior.

•Political forces relate to the influence of political and legal institutions on people and organizations.

•The increased role of government in business is one example of a political force.

•Economic forces affect the availability, production, and distribution of a society’s resources.

1.6

EXHIBIT

Management Perspectives over Time

Open (Collaborative) Innovation

The Technology-Driven Workplace

Total Quality Management

Contingency View

Systems Thinking

Quantitative (Management Science) Perspective

Humanistic Perspective

|

Classical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perspective |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2020 |

© Cengage Learning 2013

Classical Perspective

The practice of management can be traced to 3000 b.c., to the first government organizations developed by the Sumerians and Egyptians, but the formal study of management is relatively recent.48 The early study of management as we know it today began with what is now called the classical perspective.

The classical perspective on management emerged during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The factory system that began to appear in the 1800s posed challenges

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

Licensed to: CengageBrain User

Classical Perspective |

29 |

that earlier organizations had not encountered. Problems arose in tooling the plants, or- |

|

ganizing managerial structure, training employees (many of them non-English-speaking |

|

immigrants), scheduling complex manufacturing operations, and dealing with increased |

|

labor dissatisfaction and resulting strikes. |

|

These myriad new problems and the development of large, complex organizations de- |

|

manded a new approach to coordination and control, and a “new sub-species of economic |

|

man—the salaried manager”49—was born. Between 1880 and 1920, the number of profes- |

|

sional managers in the United States grew from 161,000 to more than 1 million.50 These |

|

professional managers began developing and testing solutions to the mounting challenges |

|

of organizing, coordinating, and controlling large numbers of people and increasing worker |

|

productivity. Thus began the evolution of modern management with the classical perspective. |

|

This perspective contains three subfields, each with a slightly different emphasis: scien- |

|

tific management, bureaucratic organizations, and administrative principles.51 |

|

Scientific Management |

4 |

Scientific management emphasizes scientifically determined jobs and management practices as the way to improve efficiency and labor productivity. In the late 1800s, a young engineer, Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856–1915), proposed that workers “could be retooled like machines, their physical and mental gears recalibrated for better productivity.”52 Taylor insisted that improving productivity meant that management itself would have to change and, further, that the manner of change could be determined only by scientific study; hence, the label scientific management emerged.Taylor suggested that decisions based on rules of thumb and tradition be replaced with precise procedures developed after careful study of individual situations.53

The scientific management approach is illustrated by the unloading of iron from rail cars and reloading finished steel for the Bethlehem Steel plant in 1898. Taylor calculated that with correct movements, tools, and sequencing, each man was capable of loading 47.5 tons per day instead of the typical 12.5 tons. He also worked out an incentive system that paid each man $1.85 a day for meeting the new standard, an increase from the previous rate of $1.15. Productivity at Bethlehem Steel shot up overnight.

Although known as the father of scientific management, Taylor was not alone in this area. Henry Gantt, an associate of Taylor’s, developed the Gantt chart—a bar graph that measures planned and completed work along each stage of production by time elapsed. Two other important pioneers in this area were the husband-and-wife team of Frank B. and Lillian M. Gilbreth. Frank B. Gilbreth (1868–1924) pioneered time and motion study and arrived at many of his management techniques independently of Taylor. He stressed efficiency and was known for his quest for the one best way to do work. Although Gilbreth is known for his early work with bricklayers, his work had great impact on medical surgery by drastically reducing the time patients spent on the operating table. Surgeons were able to save countless lives through the application of time and motion study. Lillian M. Gilbreth (1878–1972) was more interested in the human aspect of work. When her husband died at the age of 56, she had 12 children ages 2 to 19. The undaunted “first lady of management” went right on with her work. She presented a paper in place of her late husband, continued their seminars and consulting, lectured, and eventually became a professor at Purdue University.54 She pioneered in the field of industrial psychology and made substantial contributions to human resource management.

Exhibit 1.7 shows the basic ideas of scientific management. To use this approach, managers should develop standard methods for doing each job, select workers with the appropriate abilities, train workers in the standard methods, support workers and eliminate interruptions, and provide wage incentives.

The ideas of scientific management that began with Taylor dramatically increased productivity across all industries, and they are still important today. Indeed, the idea of engineering work for greater productivity has enjoyed a renaissance in the retail industry.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.