3 курс / Фармакология / Essential_Psychopharmacology_2nd_edition

.pdf

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

299 |

Table 8 — 1. DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder

A.Excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation), occurring more days than not for at least 6 months, about a number of events or activities (such as work or school performance)

B.Difficulty in controlling the worry

C.Anxiety and worry associated with three or more of the following six symptoms, with at least some symptoms present for more days than not for the past 6 months (Note: Only one item required for children)

1.Restless or feeling keyed up or on edge

2.Easily fatigued

3.Difficulty in concentrating or mind going blank

4.Irritability

5.Muscle tension

6.Sleep disturbance (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, or restless and unsatisfying sleep)

D.The focus of the anxiety and worry is not confined to features of an Axis I disorder. For example, the anxiety or worry is not about having a panic attack (as in panic disorder); being embarrassed in public (as in social phobia); being contaminated (as in obsessive-compulsive disorder); being away from home or close relatives (as in separation anxiety disorder); gaining weight (as in anorexia nervosa); or having a serious illness (as in hypochondriasis); and the anxiety and worry do not occur exclusively during posttraumatic stress disorder.

E.The anxiety, worry, or physical symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

F.The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse or a medication) or to a general medical condition (e.g., hyperthyroidism) and does not occur exclusively during a mood disorder, a psychotic disorder, or a pervasive developmental disorder.

the interview because chronic anxiety is rarely a stable condition (compare Figs. 8-2 to 8-4).

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is thus not a trivial disorder (Fig. 8 — 2). In fact, when one defines recovery from either major depressive disorder or GAD as reduction to only one or two symptoms with a subjective sense of returning to normal self, major depressive disorder has an 80% rate of recovery in 2 years, whereas GAD has only a 20% chance of recovery. Some patients with GAD experience a chronic state of symptomatic impairment (Fig. 8 — 3); other patients with GAD experience a waxing and waning course just above and just below the diagnostic threshold over long periods of time despite current treatment regimens (Fig. 8—4). Long-standing GAD may be a harbinger of panic disorder (Fig. 8 — 5) or major depressive disorder with or without anxiety (Fig. 8 — 6).

Drug Treatments for Anxiety

Antidepressants or Anxiolytics?

If pathological and generalized anxiety is a state of incomplete recovery from depression or from anxiety disorder subtypes, it would not be surprising if highly

300 Essential Psychopharmacology

FIGURE 8—1. Anxiety and depression can be combined in a wide variety of syndromes. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) can overlap with major depressive disorder (MDD) to form mixed anxiety depression (MAD). Subsyndromal anxiety overlapping with subsyndromal depression to form subsyndromal mixed anxiety depression, sometimes also called anxious dysthymia. Major depressive disorder can also overlap with subsyndromal symptoms of anxiety to create anxious depression; GAD can also overlap with symptoms of depression such as dysthymia to create GAD with depressive features. Thus, a spectrum of symptoms and disorders is possible, ranging from pure anxiety without depression, to various mixtures of each in varying intensities, to pure depression without anxiety.

effective treatments for depression and anxiety disorders might also be effective for generalized symptoms of anxiety. Indeed, the leading treatments for generalized anxiety today are increasingly drugs originally developed as antidepressants.

Original drug classifications in the 1960s emphasized that there were important distinctions between the antidepressants (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants) versus the anxiolytics (e.g., benzodiazepines) available at that time. This reflected the diagnostic notions then prevalent, which tended to dichotomize major depressive disorder and

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

301 |

FIGURE 8-2. Some patients with subsyndromal anxiety have an intermittent clinical course, which waxes and wanes over time between a normal state and a state of subsyndromal anxiety.

FIGURE 8 — 3. In contrast to the pattern shown in Figure 8 — 2, other patients with subsyndromal anxiety have a chronic and relatively stable yet unremitting clinical course over time.

generalized anxiety disorder while largely lumping all anxiety disorder subtypes together (Fig. 8—7).

By the 1970s and early 1980s it was recognized that certain tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors were effective in treating panic disorder and one tricyclic antidepressant (clomipramine) was effective in treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. Thus, there began to be recognized that some antidepressants overlapped with anxiolytics for the treatment of anxiety disorder subtypes or for mixtures of anxiety and depression (Fig. 8 — 8). However, either anxiolytics

302 Essential Psychopharmacology

FIGURE 8—4. Subsyndromal anxiety can also be a harbinger of an episode of a full generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Such patients may have an intermittent clinical course, which waxes and wanes over time between subsyndromal anxiety and GAD. Decompensating to full GAD with recovery only to a state of subsyndromal anxiety over time can also be called the double anxiety syndrome.

FIGURE 8 — 5. Not only may subsyndromal anxiety be a harbinger for decompensation to generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), but GAD in turn may be a harbinger for decompensation to panic disorder in some patients.

(such as benzodiazepines or buspirone) or antidepressants (such as tricyclic antidepressants or MAO inhibitors) were considered first-line treatments for some anxiety disorder subtypes.

By the 1990s antidepressants from the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class became recognized as preferred first-line treatments for anxiety disorder subtypes, ranging from obsessive-compulsive disorder, to panic disorder, and now to social phobia and posttraumatic stress disorder (Fig. 8 — 9). Not all antidepressants, however, are afficacious anxiolytics. For example, desipramine and bupropion seem to be of little help in several anxiety disorder subtypes. Documentation of efficacy

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

303 |

FIGURE 8-6. Subsyndromal mixed anxiety depression (MAD) may be an unstable psychological state, characterized by vulnerability under stress to decompensation to more severe psychiatric disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), full-syndrome MAD, or major depressive disorder (MDD).

for several of the newer antidepressants other than SSRIs in anxiety disorder subtypes is preliminary at best, but there are some positive reports and small trials of nefazodone, mirtazapine, and venlafaxine for the treatment of panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder.

Meanwhile, benzodiazepines became second-line treatments or augmentation treatments for these anxiety disorder subtypes in the 1990s. While buspirone continues to be recognized as a first-line general anxiolytic, it has not developed a convincing efficacy profile for anxiety disorder subtypes or for the treatment of major depressive disorder.

Recently, venlafaxine XR became the first agent to be approved both to treat mood in depression and anxiety in GAD. Thus, the final gap in the great divide between antidepressants and anxiolytics has been bridged (Fig. 8 — 10). It has been

304

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

305 |

attempted in the past but without success to obtain approval for numerous agents as both antidepressants and general anxiolytics. Early attempts to show that tricyclic antidepressants were also effective as general anxiolytics were promising but came after the tricyclic antidepressant era was already over. Tricyclic antidepressants appear to be slower in onset but perhaps more efficacious than even benzodiazepines for the treatment of GAD. Currently, mirtazapine and nefazodone have shown positive results in individual cases and small trials in GAD, and similar studies are currently in progress for paroxetine, but venlafaxine XR is widely recognized as effective for GAD.

Get All the Way Well, Not Just Convert Depression with Anxiety into Anxiety without Depression

Given the high degree of comorbidity of depression and generalized anxiety as well as anxiety disorder subtypes, the "holy grail" sought for a psychotropic drug has been to combine antidepressant with anxiolytic action. Otherwise, patients treated with an antidepressant that is ineffective for their comorbid anxiety states will improve their symptoms of depression and continue to suffer from symptoms of anxiety. Alternatively, two agents must be given concomitantly, one effective for the depression and the other effective for the anxiety disorder.

Depression and anxiety disorder subtypes are treated simultaneously with SSRIs, and this approach often requires only one drug. This is not always true, however, for patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and GAD. In such cases, depression is often targeted first in the hierarchy of symptoms, with the result that some patients may respond by decreasing their overall symptoms of depression but continue to have generalized symptoms of anxiety rather than remitting completely to an asymptomatic state of wellness (Table 5 — 18). Given the trend showing that some antidepressants are also anxiolytics, it may now be possible, more than ever, to eliminate symptoms of both depressed mood and anxiety in the common situation where patients have both major depressive disorder and GAD. Such a therapeutic result would return patients with comorbid depression and generalized anxiety to a state of wellness without residual symptoms of either depression or anxiety.

FIGURE 8 — 7. In the 1960s depression and its treatments were classified separately from anxiety plus anxiety disorder subtypes and their treatments.

FIGURE 8-8. In the 1970s and 1980s there began to be an overlap between the use of traditional antidepressants and traditional anxiolytics for treatment of some anxiety disorder subtypes and mixtures of depression and anxiety, but not for generalized anxiety disorder.

FIGURE 8-9. By the 1990s the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) replaced classical anxiolytics as first-line treatments for anxiety disorder subtypes and for mixtures of anxiety and depression but not for generalized anxiety disorder.

FIGURE 8 — 10. In the late 1990s the antidepressants venlafaxine XR and others have become firstline treatments for generalized anxiety disorder. Thus, antidepressants are now first-line treatments for both depression and anxiety disorders, rendering the classification of antidepressant versus anxiolytic inappropriate for many antidepressants.

306 Essential Psychopharmacology

Serotonergic Anxiolytics

Early attempts to account for the roles of serotonin (5-hydroxy-tryptamine [5HT]) in anxiety and depression by formulating the former as a serotonin dysregulation syndrome and the latter as a serotonin deficiency syndrome are naive and very imprecise oversimplifications and certainly do not explain how serotonergic antidepressants could also be treatments for anxiety. Furthermore, a serotonin partial agonist, buspirone, is recognized as a generalized anxiolytic but not as a treatment for depression or for anxiety disorder subtypes. Although some data do indeed suggest that serotonin partial agonists at the 5HT1A receptor may have antidepressant properties, some investigators remain skeptical about how powerful either the anxiolytic or antidepressant effects of this class of drugs are. The single 5HT1A agonist approved for the treatment of anxiety, buspirone, is more widely used in the United States than in many other countries, and despite over a decade of widespread clinical testing, no other 5HT1A agonist has been approved. Gepirone is still progressing as an XR formulation and tandospirone is continuing to be tested in Japan. However, the fate of many other 5HT1A agonists remains tenuous or their clinical testing has been abandoned; these drugs include flesinoxan, sunepitron, adatanserin, and ipsapirone.

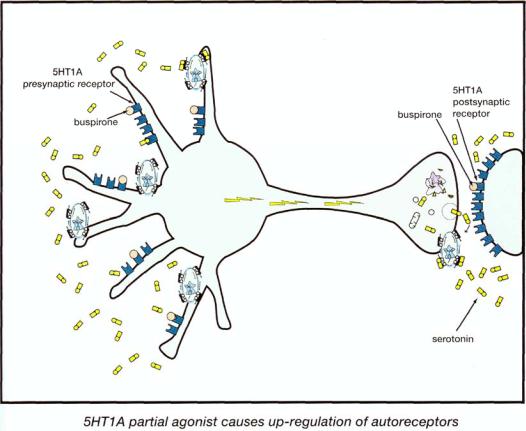

Buspirone remains the prototypical agent for the 5HT1A class of anxiolytics. Its advantages as compared with the benzodiazepines include lack of interactions with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or sedative hypnotic agents; absence of drug dependence or withdrawal symptoms with long-term use; and ease of use in patients with prior drug or alcohol abuse history. Its disadvantage as compared with the benzodiazepines is a delay in the onset of action, which is similar to the delay in therapeutic onset for the antidepressants. This has led to the belief that 5HT1A agonists exert their therapeutic effects by virtue of adaptive neuronal events and receptor events rather than simply by the acute occupancy of 5HT1A receptors by the drug, as discussed extensively above (Fig. 8 — 11). In this way, the presumed mechanism of action of 5HT1A partial agonists appears to be analogous to that of the antidepressants, which are also presumed to act by adaptations in neurotransmitter receptors, and different from that of the benzodiazepine anxiolytics, which act relatively acutely by occupancy of benzodiazepine receptors.

Buspirone tends to be used preferentially in patients with chronic and persistent anxiety, in patients with comorbid substance abuse, and in elderly patients, because it is well tolerated and has no significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions. What is clear is that buspirone shows reproducible efficacy in certain animal models of anxiety and in GAD, which points to a potentially important role of serotonin in mediating anxiety symptoms through 5HT1A receptors. Buspirone also has a role as an augmenting agent for the treatment of resistant depression, as discussed in Chapter 7.

Noradrenergic Anxiolytics

Electrical stimulation of the locus coeruleus to make it overactive creates a state analogous to anxiety in experimental animals. Thus, overactivity of norepinephrine neurons is thought to underlie anxiety states (Fig. 8—12). Indeed, examples of anx-

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

307 |

FIGURE 8 — 11. Serotonin 1A partial agonists such as buspirone may reduce anxiety by actions both at presynaptic somatodendritic autoreceptors (left) and at postsynaptic receptors (right). Presynaptic actions are more likely related to anxiolytic actions, and postsynaptic actions are perhaps more likely linked to side effects such as nausea and dizziness.

iety symptoms consistent with adrenergic overactivity include tachycardia, tremor, and sweating (Fig. 8—12).

If overactivity of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic neurons is associated with anxiety, then administration of an alpha 2 agonist should act in a manner similar to the action of norepinephrine itself on its presynaptic alpha 2 autoreceptors. Thus, anxiety can be thereby reduced because of an alpha 2 agonist stimulating these alpha 2 autoreceptors, thus "stepping on the brake" of norepinephrine release (Fig. 8—13). In fact, the alpha 2 agonist clonidine has some clinically recognized anxiolytic actions. Clonidine is especially useful in blocking the noradrenergic aspects of anxiety (tachycardia, dilated pupils, sweating, and tremor). However, it is less powerful in blocking the subjective and emotional aspects of anxiety. These same adrenergic blocking properties of clonidine due to its stimulation of alpha 2 presynaptic autoreceptors have been successfully applied to reducing the adrenergic symptoms pro-

FIGURE 8 — 12. Overactivity of norepinephrine neurons is associated with anxiety and may mediate the autonomic symptoms associated with anxiety, such as tachycardia, dilated pupils, tremor, and sweating. Shown here are hyperactive norepinephrine neurons with their axons projecting forward to the cerebral cortex from their cell bodies in the locus coeruleus.

308