3 курс / Фармакология / Essential_Psychopharmacology_2nd_edition

.pdf

|

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

329 |

|

Table 8—4. Sedative-hypnotic agents |

|

Novel nonbenzodiazepines |

Sedating antihistamines (may be available |

|

Rapid-onset, short-acting |

over the counter) |

|

Zaleplon Zolpidem |

Diphenhydramine |

|

Zopiclone |

Doxylamine |

|

Benzodiazepines |

Hydroxyzine |

|

|

|

|

Rapid-onset, short-acting Triazolam Delayed onset,

intermediate-acting Temazepam

Estazolam Rapid onset, long-acting

Flurazepam

Quazepam

Sedating antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants Trazodone Mirtazapine Nefazodone

Sedating anticholinergic (over the counter)

Scopolamine

Natural products

Melatonin

Valerian

Older sedative-hypnotics

Chloral hydrate

awakening in the middle of the night will still allow the drug to wear off by the time of arising in the morning.

Zolpidem (Fig. 8—29). This was the first omega 1 selective nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotic and rapidly replaced benzodiazepines as the preferred agent for many patients and prescribers. It has a somewhat later peak drug concentration (2 to 3 hours) and longer half-life (1.5 to 3 hours) than zaleplon.

Zopiclone (Fig. 8—30). This agent is available outside the United States and has a slightly later peak drug concentration than zaleplon but a more rapid peak than zolpidem. However, its half-life (3.5 to 6 hours) is much longer than that of either zaleplon or zolpidem.

Sedative-Hypnotic Benzodiazepines

The benzodiazepines are still widely prescribed for the treatment of insomnia. These agents have been extensively discussed above in terms of their mechanism of action and use in anxiety. Their mechanism of action in insomnia is the same as for anxiety (see Figs. 8—23 to 8-25). Whether a benzodiazepine is used for sedation or for anxiety is based largely on half-life, with the shorter half-life drugs preferred for insomnia because they are more likely to wear off by morning. However, in practice virtually all the benzodiazepines are used for the treatment of insomnia (Table 8- 4).

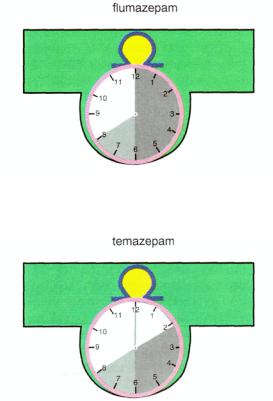

Pharmacokinetics differ significantly among the most widely used benzodiazepine hypnotics, with some such as triazolam (Fig. 8-31) having rapid onset and short

330 Essential Psychopharmacology

FIGURE 8 — 31. The hypnotic agent triazolam is a sedating benzodiazepine with a short duration of action.

half-life, some such as flurazepam (Fig. 8 — 32) having relatively rapid onset but prolonged half-life, and others such as temazepam (Fig. 8 — 33) having somewhat delayed onset but intermediate half-life (Table 8—4). Ideally, the pattern of sleep disturbance should be matched to the sedative-hypnotic, especially since there are so many choices of how to customize a therapy for an individual patient. If a patient has difficulty getting to sleep, a fast-onset, short-acting agent should be considered. If a patient has middle-of-the-night insomnia, an intermediate-onset, intermediateacting benzodiazepine might be best, especially if the short-acting agents are not effective. If a patient has problems both falling asleep and staying asleep, a fastonset, intermediate-acting agent might be needed.

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

331 |

FIGURE 8-32. The hypnotic agent flumazepam is a sedating benzodiazepine with a long duration of action.

FIGURE 8-33. The hypnotic agent is a sedating benzodiazepine with a somewhat delayed onset of action and intermediate duration of action.

There are several problems with using benzodiazepines for the treatment of insomnia. Short-term difficulties associated with benzodiazepine use for insomnia are usually related to giving too high a dose for an individual patient. In such cases, there are carryover effects the morning after administration, including not only a "drugged feeling" and the persistence of sedation when the patient wants to be alert, but also interference with memory formation once the patient is awake. These problems can often be handled by reducing the dose of the benzodiazepine, using a shorter half-life benzodiazepine, or switching to a short-acting nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic, particularly in elderly patients.

Longer-term difficulties associated with benzodiazepine use for insomnia come from observations that many patients develop tolerance for these agents, so that they stop working after a week or two. To avoid this, patients must take a sleeping pill only a few times within several days, or for only about 10 days in a row followed by several days or weeks with no drug treatment. Furthermore, if patients persist in taking benzodiazepines as sedative-hypnotics for several weeks to months, there can be a withdrawal syndrome once the medications are stopped, particularly if they are stopped suddenly. This is discussed in further detail in Chapter 13.

Discontinuance of benzodiazepines as sedative-hypnotics in patients who have been taking them for a prolonged time can cause a condition called rebound insomnia,

332Essential Psychopharmacology

in which a patient's insomnia worsens as soon as benzodiazepines are stopped. Although this condition can be avoided by short-term or only intermittent use of benzodiazepines as sedative-hypnotics, it is often masked in long-term benzodiazepine users until they suddenly stop their medication. Treatment of those grown tolerant to the use of sedative-hypnotic benzodiazepines involves a program of tapered withdrawal, discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

Antidepressants with Sedative-Hypnotic Properties

There are also numerous antidepressants that have sedative-hypnotic properties (Table 8—4). Some of these antidepressants are sedating owing to anticholinergicantihistaminic actions. Not surprisingly, the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) can therefore be useful hypnotics to induce sleep in some patients. Thus, skillful use of a TCA in a depressed patient with insomnia can turn the liability of unwanted sedation into the asset of relief of insomnia if the TCA is given at bedtime. This property, as discussed in Chapter 6, has nothing to do, however, with the reason that TCAs are antidepressants (shown in Figs. 6—15 and 6—16).

Another antidepressant, namely trazodone, also has significant sedating properties. This may be due to its serotonin 2A antagonist properties, which may act to induce and restore slow-wave sleep (Fig. 7 — 14). Trazodone can be used safely with most other psychotropic drugs and so is a popular choice when a patient must take another medication that disrupts sleep, such as an SSRI. Other sedating antidepressants that block serotonin 2A receptors include mirtazapine and nefazodone. These agents are occasionally also used for their sedative-hypnotic properties.

Over-the-Counter Agents

Numerous nonprescription agents (sleeping pills) are popular with the general public (Table 8—4). Although there are trade names that differ widely from time to time and from country to country, essentially all over-the-counter sleeping pills contain one or more of three active ingredients: (1) the anticholinergic agent scopolamine;

(2) an antihistamine that also has anticholinergic properties; and (3) a mild pain reliever. Antihistaminergic and anticholinergic properties have already been discussed in relationship to tricyclic antidepressants. Sleep induction by these agents occurs at the expense of side effects such as dry mouth, blurred vision, and constipation. They can even cause confusion or memory problems, particularly in the elderly. However, they are not truly dependence-forming, do not cause severe sleep problems when withdrawn, and are generally safe in the doses available over the counter.

In recent years, natural products such as melatonin and herbs such as valerian have become popular over-the-counter remedies for insomnia. There are no comprehensive evaluations of safety and efficacy of these products. Beyond questions of safety and efficacy, there is no consensus on what their doses should be. Nevertheless, these products continue to be used widely by some patients.

Other Nonbenzodiazepines as Sedative-Hypnotics

Various older agents have an extensive prior history of use as sedative-hypnotics. These include barbiturates and related compounds such as ethclorvynol and ethin-

Anxiolytics and Sedative-Hypnotics |

333 |

amate; chloral hydrate and derivatives; and piperidinedione derivatives such as glutethimide and methyprylon. Because of problems of tolerance, abuse, dependence, overdose, and several withdrawal reactions far more severe than those associated with the benzodiazepines, barbiturates and piperidinedione derivatives are rarely prescribed as sedative-hypnotics today. Chloral hydrate is still somewhat commonly used because it can be an effective short-term sedative-hypnotic and is inexpensive. However, it is generally to be avoided in patients with severe renal, hepatic, and cardiac disease and in those who are taking numerous other drugs because of its ability to affect hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes. The potential of chloral hydrate to induce tolerance, physical dependence, and addiction requires cautious use in those with histories of drug or alcohol abuse problems and only short-term use in any patient.

Summary

In this chapter we have provided clinical descriptions of anxiety and insomnia. We have also described the biological basis for anxiety and insomnia, emphasizing three neurotransmitter systems: GABA-benzodiazepines, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Finally, we have discussed the treatments for anxiety and insomnia and how they play on these three neurotransmitter systems.

In discussing the GABA neurotransmitter system, we have shown how benzodiazepines are allosteric modulators of GABA-A receptors and in turn, of inhibitory chloride channels. The benzodiazepine receptor may be involved in the mediation of the emotion of anxiety as well as in the mechanism of anxiolytic drug action.

In terms of the noradrenergic system, this chapter has described the locus coeruleus as that part of the brain containing the noradrenergic neurons that mediate some of the symptoms of anxiety through alpha 2 and beta adrenergic receptors. Our discussion has also extended to the role of serotonin in anxiety, which appears to be key, yet quite complex and incompletely understood. One current theory developed in this chapter is the notion that anxiolytic drugs act as partial agonists at serotonin 1A receptors.

We have discussed how various antidepressants, especially venlafaxine XR, are being used increasingly for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Buspirone remains a first-line generalized anxiolytic for chronic anxiety, and benzodiazepines are used largely for short-term treatment of intermittent anxiety symptoms.

The nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics zaleplon, zolpidem, and zopiclone are replacing benzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics as first-line treatments for insomnia. Some antidepressants, such as sedating tricyclic antidepressants and trazodone, are also used as sedative-hypnotic agents for the treatment of insomnia.

CHAPTER 9

DRUG TREATMENTS FOR OBSESSIVE-

COMPULSIVE DISORDER, PANIC

DISORDER, AND PHOBIC DISORDERS

I.Obsessive-compulsive disorder

A.Clinical description

B.Biological basis

1.The serotonin hypothesis

2.Dopamine and obsessive-compulsive disorder

3.Serotonin-dopamine hypothesis

4.Neuroanatomy

C.Drug treatments

1.Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

2.Adjunctive treatments

3.New prospects

II.Panic attacks and panic disorder

A.Clinical description

B.Biological basis

1.Neurotransmitter dysregulation

2.Respiratory hypotheses

3.Neuroanatomic findings

C.Treatments

1.Serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors

2.Newer antidepressants

3.Tricyclic antidepressants

4.Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

5.Benzodiazepines

6.Cognitive and behavioral psychotherapies

7.Combination therapies

8.Relapse after medication discontinuation

9.New prospects

III. Phobic disorders: specific phobias, social phobia, and agoraphobia

A.Clinical description of phobias and phobic disorders

335

336Essential Psychopharmacology

B.Biological basis of social phobia

C.Drug treatments for social phobia

D.Psychotherapeutic treatments

E.New prospects

IV. Posttraumatic stress disorder

A.Clinical description

B.Biological basis

C.Treatments V. Summary

Impressive advances are being made in the treatment of anxiety disorders. These treatments have largely derived from the new antidepressants, as essentially all new treatments for the anxiety disorders are also antidepressants. Thus, a good deal of the information on the drugs and their mechanisms of action will be found in Chapters 6 and 7 on antidepressants. The adaptation of antidepressants as significant new treatments for anxiety disorders has had a large hand in the remaking of diagnostic criteria for subtypes of anxiety disorder. Thus, the tasks of clarifying the clinical description, epidemiology, and natural history of obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder were greatly facilitated once effective new treatments became available over the past decade.

The anxiety disorders as a group are the most common psychiatric disorders and therefore very important for the psychopharmacologist to understand and treat effectively. Knowledge about the anxiety disorders is advancing at a rapid pace, and new treatments and diagnostic criteria are still evolving. To equip the reader with the necessary foundation to keep up with the pace of change in the anxiety disorders, this chapter will set forth the psychopharmacological principles underlying contemporary treatment strategies for them. The details are likely to change rapidly, so this chapter will emphasize underlying concepts rather than specific facts about drug doses and pragmatic prescribing information. The reader is referred to standard reference sources for such data. Here we will emphasize the therapeutic agents, and their pharmacological mechanisms of action for the treatment of the most prominent anxiety disorders in psychopharmacology, namely, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Generalized anxiety disorder was discussed in Chapter 8.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Clinical Description

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a syndrome characterized by obsessions and/ or compulsions, which together last at least an hour per day and are sufficiently bothersome that they interfere with one's normal social or occupational functioning. Obsessions are experienced internally and subjectively by the patient as thoughts, impulses, or images. According to standard definitions in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), obsessions are intrusive and inappropriate and cause marked anxiety and distress. Common obsessions are listed in Table 9-1.

Drug Treatments for Obsessive-Compulsive, Panic, and Phobic Disorders |

337 |

Table 9—1. Common obsessions

Contamination

Aggression

Religion (scrupulosity)

Safety/harm

Need for exactness or symmetry

Somatic (body) fears

Table 9 — 2. Common compulsions

Checking

Cleaning/washing

Counting

Repeating

Ordering/arranging

Hoarding/collecting

Compulsions, on the other hand, are repetitive behaviors or purposeful mental acts that are sometimes observed by family members or clinicians, whereas it is not possible to observe an obsession. Patients are often subjectively driven to act out their compulsions either in response to an obsession or according to rigid rules aimed at preventing distress or some dreaded event. Unfortunately, the compulsions are not realistically able to prevent the distress or the dreaded event, and at some level the patient generally recognizes this. Common compulsions are listed in Table 9— 2. The formal DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for OCD are given in Table 9 — 3. Numerous other psychiatric disorders that are considered by some experts to be related to OCD are listed as OCD Spectrum Disorders in Table 9-4. These include conditions such as pathological gambling, eating disorders, paraphilias, kleptomania, body dysmorphic disorder, and several others.

Interest in OCD skyrocketed once clomipramine was recognized throughout the world to be an effective treatment in the mid-1980s. Originally thought to be a rare condition, recent epidemiological studies now suggest that OCD exists in about 1 out of every 50 adults and in about 1 out of every 200 children. Thus, as news that OCD is common and treatable emerged, intensive research efforts began to document that all five serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and certain forms of behavioral therapy are also effective treatments for OCD. The initial euphoria of the 1980s is somewhat balanced today by the sobering realization that treatments ameliorate but do not eliminate OCD symptoms in many patients, and that relapse is very common after discontinuing treatments for OCD.

Biological Basis

Despite a great deal of work in this area, the biological basis for OCD remains unknown. Some data suggest a genetic component to the etiology of OCD, but

338 Essential Psychopharmacology

Table 9 — 3. DSM IV diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder

1.Either obsessions or compulsions Obsessions denned by

a.Recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images that are experienced, at some time during the disturbance, as intrusive and inappropriate and that cause marked anxiety or distress.

b.The thoughts, impulses, or images are not simply excessive worries about real-life problems.

c.The person attempts to ignore or suppress such thoughts, impulses, or images or to neutralize them with some other thought or action.

d.The person recognizes that the obsessional thoughts, impulses, or images are a product of his or her own mind and not imposed from without as in thought insertion.

Compulsions defined by

a.Repetitive behaviors (e.g., hand washing, ordering, checking) or mental acts (e.g., praying, counting, repeating words silently) that the person feels driven to perform in response to an obsession or according to rules that must be applied rigidly.

b.The behaviors or mental acts are aimed at preventing or reducing distress or preventing some dreaded event or situation; however, these behaviors or mental acts either are not connected in a realistic way with what they are designed to neutralize or prevent or they are clearly excessive.

2.At some point during the course of the disorder, the person has recognized that the obsessions or compulsions are excessive or unreasonable (this does not apply to children).

3.The obsessions or compulsions caused marked distress, are time-consuming (take more than 1 hour per day), or significantly interfere with occupational or academic functioning or with usual social activities or relationships.

4.If another Axis I disorder is present, the content of the obsessions or compulsions is nor restricted to it (e.g., preoccupation with food in the presence of an eating disorder; hair pulling in the presence of trichotillomania; concern with appearance in the presence of body dysmorphic disorder; preoccupation with drugs in the presence of a substance abuse disorder; preoccupation with having a serious illness in the presence of hypochondriasis; preoccupation with sexual urges or fantasies in the presence of a paraphilia; or guilty ruminations in the presence of major depressive disorder.

5.The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse or a medication) or a general medical condition.

abnormal genes or gene products have yet to be identified. Some evidence implicates abnormal neuronal activity as well as alterations in neurotransmitters in OCD patients, but it is not known whether this is a cause or an effect of OCD. There is also a long-standing belief that there is a neurologic basis for OCD, which derives mainly from data implicating the basal ganglia in OCD plus the relative success of psychosurgery in some patients.

The serotonin hypothesis. Although it is unlikely that one neurotransmitter system can explain all the complexities of OCD, recent efforts to elucidate the pathophysiology of OCD have centered largely around the role of the neurotransmitter serotonin