- •Table of Contents

- •Copyright

- •Dedication

- •Introduction to the eighth edition

- •Online contents

- •List of Illustrations

- •List of Tables

- •1. Pulmonary anatomy and physiology: The basics

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Abnormalities in gas exchange

- •Suggested readings

- •2. Presentation of the patient with pulmonary disease

- •Dyspnea

- •Cough

- •Hemoptysis

- •Chest pain

- •Suggested readings

- •3. Evaluation of the patient with pulmonary disease

- •Evaluation on a macroscopic level

- •Evaluation on a microscopic level

- •Assessment on a functional level

- •Suggested readings

- •4. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of airways

- •Structure

- •Function

- •Suggested readings

- •5. Asthma

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •6. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach and assessment

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •7. Miscellaneous airway diseases

- •Bronchiectasis

- •Cystic fibrosis

- •Upper airway disease

- •Suggested readings

- •8. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of the pulmonary parenchyma

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Suggested readings

- •9. Overview of diffuse parenchymal lung diseases

- •Pathology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Suggested readings

- •10. Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases associated with known etiologic agents

- •Diseases caused by inhaled inorganic dusts

- •Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- •Drug-induced parenchymal lung disease

- •Radiation-induced lung disease

- •Suggested readings

- •11. Diffuse parenchymal lung diseases of unknown etiology

- •Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- •Other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias

- •Pulmonary parenchymal involvement complicating systemic rheumatic disease

- •Sarcoidosis

- •Miscellaneous disorders involving the pulmonary parenchyma

- •Suggested readings

- •12. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of the pulmonary vasculature

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Suggested readings

- •13. Pulmonary embolism

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic evaluation

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •14. Pulmonary hypertension

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic features

- •Specific disorders associated with pulmonary hypertension

- •Suggested readings

- •15. Pleural disease

- •Anatomy

- •Physiology

- •Pleural effusion

- •Pneumothorax

- •Malignant mesothelioma

- •Suggested readings

- •16. Mediastinal disease

- •Anatomic features

- •Mediastinal masses

- •Pneumomediastinum

- •Suggested readings

- •17. Anatomic and physiologic aspects of neural, muscular, and chest wall interactions with the lungs

- •Respiratory control

- •Respiratory muscles

- •Suggested readings

- •18. Disorders of ventilatory control

- •Primary neurologic disease

- •Cheyne-stokes breathing

- •Control abnormalities secondary to lung disease

- •Sleep apnea syndrome

- •Suggested readings

- •19. Disorders of the respiratory pump

- •Neuromuscular disease affecting the muscles of respiration

- •Diaphragmatic disease

- •Disorders affecting the chest wall

- •Suggested readings

- •20. Lung cancer: Etiologic and pathologic aspects

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Suggested readings

- •21. Lung cancer: Clinical aspects

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Principles of therapy

- •Bronchial carcinoid tumors

- •Solitary pulmonary nodule

- •Suggested readings

- •22. Lung defense mechanisms

- •Physical or anatomic factors

- •Antimicrobial peptides

- •Phagocytic and inflammatory cells

- •Adaptive immune responses

- •Failure of respiratory defense mechanisms

- •Augmentation of respiratory defense mechanisms

- •Suggested readings

- •23. Pneumonia

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features and initial diagnosis

- •Therapeutic approach: General principles and antibiotic susceptibility

- •Initial management strategies based on clinical setting of pneumonia

- •Suggested readings

- •24. Bacterial and viral organisms causing pneumonia

- •Bacteria

- •Viruses

- •Intrathoracic complications of pneumonia

- •Respiratory infections associated with bioterrorism

- •Suggested readings

- •25. Tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteria

- •Etiology and pathogenesis

- •Definitions

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical manifestations

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Principles of therapy

- •Nontuberculous mycobacteria

- •Suggested readings

- •26. Miscellaneous infections caused by fungi, including Pneumocystis

- •Fungal infections

- •Pneumocystis infection

- •Suggested readings

- •27. Pulmonary complications in the immunocompromised host

- •Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- •Pulmonary complications in non–HIV immunocompromised patients

- •Suggested readings

- •28. Classification and pathophysiologic aspects of respiratory failure

- •Definition of respiratory failure

- •Classification of acute respiratory failure

- •Presentation of gas exchange failure

- •Pathogenesis of gas exchange abnormalities

- •Clinical and therapeutic aspects of hypercapnic/hypoxemic respiratory failure

- •Suggested readings

- •29. Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- •Physiology of fluid movement in alveolar interstitium

- •Etiology

- •Pathogenesis

- •Pathology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Clinical features

- •Diagnostic approach

- •Treatment

- •Suggested readings

- •30. Management of respiratory failure

- •Goals and principles underlying supportive therapy

- •Mechanical ventilation

- •Selected aspects of therapy for chronic respiratory failure

- •Suggested readings

- •Index

are employed.

After the development of delayed hypersensitivity, the pathologic hallmarks of tuberculosis are granulomas and caseous necrosis, often with cavity formation.

A process of healing tends to occur at the sites of disease. Fibrosis or scarring ensues, often associated with contraction of the affected area and the deposition of calcium. When the Ghon complex undergoes progressive fibrosis and calcification, it is referred to as a Ranke complex. With severe disease, extensive destruction of lung tissue results from large areas of inflammation, granuloma formation, caseous necrosis, and cavitation, along with fibrosis, contraction, and foci of calcification. Importantly, much of the destruction that occurs during tuberculosis requires an intact cellular immune system and appears to be due to the host inflammatory response attempting to contain the infection. Thus, patients with advanced HIV disease and other marked immune defects often have an atypical presentation in which the organism is widely disseminated but there is little evidence of cavitation and fibrosis.

Tuberculosis can spread hematogenously, and dissemination of organisms through the bloodstream at the time of primary infection is probably the rule rather than the exception. When defense mechanisms break down, disease can become apparent at other sites (e.g., liver, kidney, adrenal glands, bones, central nervous system). Spread also occurs to other regions of the lung, either due to hematogenous seeding during the primary infection or because of the spilling of infected secretions or caseous material into the bronchi and other regions of the lung.

Within the lung, characteristic locations for reactivation tuberculosis are the apical regions of the upper lobes and, to a lesser extent, the superior segment of the lower lobes. It is believed these are not sites of primary infection but rather the favored location for implantation of organisms after hematogenous spread. These regions have a relatively high ventilation-perfusion ratio, resulting in a high PO2 and making them particularly suitable for survival of the aerobic tubercle bacilli.

Pathophysiology

Most of the clinical features of pulmonary tuberculosis can be attributed to one of two aspects of the disease: the presence of a poorly controlled chronic infection, or a chronic destructive process within the lung parenchyma. A variety of other manifestations result from extrapulmonary spread of tuberculosis, but these consequences are not considered here.

Chronic tuberculosis infection within the lung is associated with systemic manifestations of widespread inflammation. As implied by the term “consumption,” which was so frequently used in the past, tuberculosis is a disease in which systemic manifestations, such as fatigue, weight loss, cachexia, and loss of appetite, are prominent features. These and other systemic effects of tuberculosis are discussed in the section on clinical manifestations.

The chronic destructive process involving the pulmonary parenchyma entails progressive scarring and loss of lung tissue. However, respiratory function is generally preserved more than would be expected, perhaps because the disease often is limited to the apical and posterior regions of the upper lobes as well as to the superior segment of the lower lobes. Oxygenation also tends to be surprisingly preserved, presumably because ventilation and perfusion are destroyed simultaneously in the affected lung. Consequently, ventilation-perfusion mismatch is not nearly so great as in many other parenchymal and airway diseases.

Clinical manifestations

There is an important distinction—and important clinical differences—between latent tuberculous infection and tuberculous disease (active tuberculosis). Latent tuberculous infection is the consequence of primary exposure, by which the bacilli have become established in the patient; however, host defense mechanisms have prevented any clinically apparent disease. Specific immunity to the tubercle bacillus can be demonstrated by a positive reaction to a skin test for delayed hypersensitivity or a positive IGRA; otherwise, there is no evidence for proliferation of bacteria or for tissue involvement by disease. Patients with infection but without disease are not contagious. In contrast, tuberculous disease is associated with proliferation of organisms, accompanied by a tissue response and generally (although not always) clinical problems of which the patient is aware.

Patients with pulmonary tuberculosis can manifest (1) systemic symptoms, (2) symptoms referable to the respiratory tract, or (3) an abnormal finding on chest radiograph but no clinical symptoms. When symptoms occur, they are generally insidious or subacute rather than acute in onset.

Systemic symptoms are often relatively nonspecific: weight loss, anorexia, fatigue, low-grade fever, and night sweats. The most common symptoms resulting from pulmonary involvement are cough, sputum production, and hemoptysis; chest pain occasionally is present. Many patients have neither systemic nor pulmonary symptoms, and come to the attention of a physician because of an abnormal finding on chest radiograph, which is often performed for an unrelated reason.

Patients with extrapulmonary involvement frequently have pulmonary tuberculosis as well, but occasional cases are limited to an extrapulmonary site. The pericardium, pleura, kidney, peritoneum, adrenal glands, bones, and central nervous system each may be involved, with symptoms resulting from the organ or region affected. With miliary tuberculosis, the disease is disseminated, and patients usually are systemically quite ill.

Physical examination of the patient with pulmonary tuberculosis may show the ravages of a chronic infection with evidence of wasting and weight loss. This presentation is uncommon in patients with access to treatment, but it is frequently seen in under-resourced settings. Findings on chest examination tend to be relatively insignificant, although sometimes crackles or rales are heard over affected areas. If a tuberculous pleural effusion is present, the physical findings characteristic of an effusion may be found.

Common presenting problems with tuberculosis:

1.Systemic symptoms: fatigue, weight loss, fever, night sweats

2.Pulmonary symptoms: cough, sputum production, hemoptysis

3.Abnormal chest radiographic findings

Diagnostic approach

The tuberculin skin test, a commonly used diagnostic tool, documents tuberculous infection rather than active disease. A small amount of protein derived from the tubercle bacillus (purified protein derivative [PPD]) is injected intradermally on the inner surface of the forearm. Individuals who have been infected by M. tuberculosis and have acquired cellular immunity to the organism demonstrate a positive test reaction, seen as induration or swelling at the site of injection after 48 to 72 hours. The criteria for determining a positive skin test reaction vary according to the clinical setting, specifically the presence or absence of immunosuppression and/or epidemiologic risk factors affecting the likelihood of previous exposure to tuberculosis. Importantly, the test does not distinguish between individuals who have active tuberculosis and those who merely have acquired delayed hypersensitivity from previous infection. However, because reactivation tuberculosis occurs in patients with previous tuberculous infection, a

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/

positive skin test reaction does identify individuals at higher risk for the subsequent development of active disease.

As with most diagnostic tests, false-negative results can occur with the tuberculin skin test. Faulty administration, a less bioactive batch of skin-testing material, and underlying diseases that depress cellular immunity, such as HIV or even advanced tuberculosis itself, are several causes of false-negative skin test reactions. On the other hand, not all patients who react to tuberculoprotein have been exposed to M. tuberculosis. Infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria, often called atypical mycobacteria, is sometimes associated with a positive or a borderline positive skin test reaction to PPD.

The IGRA, a blood test, is an alternative to skin testing. Blood is drawn, and the patient’s T cells are incubated with M. tuberculosis antigens. Cells from previously sensitized individuals will release IFN-γ in response to the antigens, and the IFN-γ is detected by an enzyme-linked assay. Tuberculin skin testing does not require laboratory facilities and globally remains more commonly performed than IFN-γ assays. However, because the blood tests do not require the patient to return for an additional office visit for interpretation, IGRA has the advantages of fewer patients lost to follow-up. These assays are unaffected by prior bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination (see section on principles of therapy) or exposure to most atypical mycobacteria, but false-positive results still can occur in individuals exposed to or infected with Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium kansasii.

For the diagnosis of tuberculosis (i.e., actual tuberculous disease), an important initial diagnostic tool is the chest radiograph. In primary disease, the chest radiograph may show a nonspecific infiltrate, often —but certainly not exclusively—in the lower lobes (in contrast to the upper lobe predominance of reactivation disease). Hilar (and sometimes paratracheal) lymph node enlargement may be present, reflecting involvement of the draining node by the organism and by the primary infection. Pleural involvement may be seen, with the development of a pleural effusion.

Common features of the chest radiograph in primary tuberculosis:

1.Nonspecific infiltrate (often lower lobe)

2.Hilar (and paratracheal) node enlargement

3.Pleural effusion

When the primary disease heals, the chest radiograph frequently shows some residua of the healing process. Most common are small, calcified lesions within the pulmonary parenchyma, reflecting a collection of calcified granulomas. Calcification within hilar or paratracheal lymph nodes may be seen. The radiographic terminology can be confusing as it is commonly used. The term granuloma is a pathologic term that describes a microscopic collection of lymphocytes and histiocytes. A calcified nodule on a chest radiograph is frequently called a calcified granuloma, but it really represents a small mass of numerous microscopic granulomas.

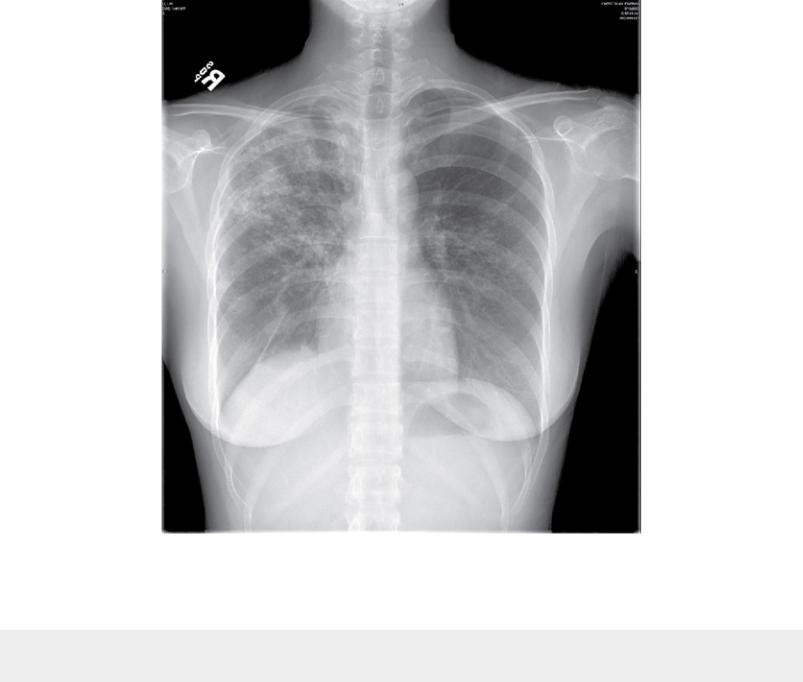

With reactivation tuberculosis, the most common sites of disease are the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes and, to a lesser extent, the superior segment of the lower lobes. A variety of patterns can be seen: infiltrates, cavities, nodules, and scarring and contraction (Fig. 25.2). The presence of abnormal findings on a chest radiograph does not necessarily indicate active disease. The disease may be old, stable, and currently inactive, and it is difficult, if not impossible, to gauge activity solely based on radiographic appearance.

FIGURE 25.2 Chest radiograph of patient with reactivation tuberculosis. Note

infiltrates in the right lung, primarily in the right upper lobe.

Radiographic location of reactivation tuberculosis: most commonly apical and posterior segments of upper lobe(s), superior segment of lower lobe(s).

The definitive diagnosis of tuberculosis rests on culturing the organism from either secretions (e.g., sputum) or tissue, but the organisms are slow growing, with up to 6 weeks required for growth and final identification. Culture of the organism is important for confirmation of the diagnosis and for testing sensitivity to antituberculous drugs, particularly considering rising resistance to some of the commonly used antituberculous agents. Molecular genetic testing now permits earlier identification of certain types of drug resistance than do traditional methods of culture and sensitivity testing.

Another extremely useful procedure that can provide results almost immediately is staining of material obtained from the tracheobronchial tree. The specimens obtained can be sputum, expectorated either spontaneously or following inhalation of an irritating aerosol (sputum induction), or washings or biopsy samples obtained by flexible bronchoscopy. Although they stain positive with Gram stain, a hallmark of mycobacterial organisms is their ability to retain certain dyes even after exposure to acid. Their acid-fast property is generally demonstrated with Ziehl-Neelsen or Kinyoun stain, or with a fluorescent stain that uses auramine-rhodamine. The finding of a single acid-fast bacillus from sputum or tracheobronchial washings is clinically significant in the majority of cases. One qualification is that nontuberculous

mycobacteria, which either cause less severe disease or are present as colonizing organisms or

Данная книга находится в списке для перевода на русский язык сайта https://meduniver.com/