- •Preface

- •Foreword

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Medical History

- •1.1 Congestive Heart Failure

- •1.2 Angina Pectoris

- •1.3 Myocardial Infarction

- •1.4 Rheumatic Heart Disease

- •1.5 Heart Murmur

- •1.6 Congenital Heart Disease

- •1.7 Cardiac Arrhythmia

- •1.8 Prosthetic Heart Valve

- •1.9 Surgically Corrected Heart Disease

- •1.10 Heart Pacemaker

- •1.11 Hypertension

- •1.12 Orthostatic Hypotension

- •1.13 Cerebrovascular Accident

- •1.14 Anemia and Other Blood Diseases

- •1.15 Leukemia

- •1.16 Hemorrhagic Diatheses

- •1.17 Patients Receiving Anticoagulants

- •1.18 Hyperthyroidism

- •1.19 Diabetes Mellitus

- •1.20 Renal Disease

- •1.21 Patients Receiving Corticosteroids

- •1.22 Cushing’s Syndrome

- •1.23 Asthma

- •1.24 Tuberculosis

- •1.25 Infectious Diseases (Hepatitis B, C, and AIDS)

- •1.26 Epilepsy

- •1.27 Diseases of the Skeletal System

- •1.28 Radiotherapy Patients

- •1.29 Allergy

- •1.30 Fainting

- •1.31 Pregnancy

- •Bibliography

- •2.1 Radiographic Assessment

- •2.2 Magnification Technique

- •2.4 Tube Shift Principle

- •2.5 Vertical Transversal Tomography of the Jaw

- •Bibliography

- •3. Principles of Surgery

- •3.1 Sterilization of Instruments

- •3.2 Preparation of Patient

- •3.3 Preparation of Surgeon

- •3.4 Surgical Incisions and Flaps

- •3.5 Types of Flaps

- •3.6 Reflection of the Mucoperiosteum

- •3.7 Suturing

- •Bibliography

- •4.1 Surgical Unit and Handpiece

- •4.2 Bone Burs

- •4.3 Scalpel (Handle and Blade)

- •4.4 Periosteal Elevator

- •4.5 Hemostats

- •4.6 Surgical – Anatomic Forceps

- •4.7 Rongeur Forceps

- •4.8 Bone File

- •4.9 Chisel and Mallet

- •4.10 Needle Holders

- •4.11 Scissors

- •4.12 Towel Clamps

- •4.13 Retractors

- •4.14 Bite Blocks and Mouth Props

- •4.15 Surgical Suction

- •4.16 Irrigation Instruments

- •4.17 Electrosurgical Unit

- •4.18 Binocular Loupes with Light Source

- •4.19 Extraction Forceps

- •4.20 Elevators

- •4.21 Other Types of Elevators

- •4.22 Special Instrument for Removal of Roots

- •4.23 Periapical Curettes

- •4.24 Desmotomes

- •4.25 Sets of Necessary Instruments

- •4.26 Sutures

- •4.27 Needles

- •4.28 Local Hemostatic Drugs

- •4.30 Materials for Tissue Regeneration

- •Bibliography

- •5. Simple Tooth Extraction

- •5.1 Patient Position

- •5.2 Separation of Tooth from Soft Tissues

- •5.3 Extraction Technique Using Tooth Forceps

- •5.4 Extraction Technique Using Root Tip Forceps

- •5.5 Extraction Technique Using Elevator

- •5.6 Postextraction Care of Tooth Socket

- •5.7 Postoperative Instructions

- •Bibliography

- •6. Surgical Tooth Extraction

- •6.1 Indications

- •6.2 Contraindications

- •6.3 Steps of Surgical Extraction

- •6.4 Surgical Extraction of Teeth with Intact Crown

- •6.5 Surgical Extraction of Roots

- •6.6 Surgical Extraction of Root Tips

- •Bibliography

- •7.1 Medical History

- •7.2 Clinical Examination

- •7.3 Radiographic Examination

- •7.4 Indications for Extraction

- •7.5 Appropriate Timing for Removal of Impacted Teeth

- •7.6 Steps of Surgical Procedure

- •7.7 Extraction of Impacted Mandibular Teeth

- •7.8 Extraction of Impacted Maxillary Teeth

- •7.9 Exposure of Impacted Teeth for Orthodontic Treatment

- •Bibliography

- •8.1 Perioperative Complications

- •8.2 Postoperative Complications

- •Bibliography

- •9. Odontogenic Infections

- •9.1 Infections of the Orofacial Region

- •Bibliography

- •10. Preprosthetic Surgery

- •10.1 Hard Tissue Lesions or Abnormalities

- •10.2 Soft Tissue Lesions or Abnormalities

- •Bibliography

- •11.1 Principles for Successful Outcome of Biopsy

- •11.2 Instruments and Materials

- •11.3 Excisional Biopsy

- •11.4 Incisional Biopsy

- •11.5 Aspiration Biopsy

- •11.6 Specimen Care

- •11.7 Exfoliative Cytology

- •11.8 Tolouidine Blue Staining

- •Bibliography

- •12.1 Clinical Presentation

- •12.2 Radiographic Examination

- •12.3 Aspiration of Contents of Cystic Sac

- •12.4 Surgical Technique

- •Bibliography

- •13. Apicoectomy

- •13.1 Indications

- •13.2 Contraindications

- •13.3 Armamentarium

- •13.4 Surgical Technique

- •13.5 Complications

- •Bibliography

- •14.1 Removal of Sialolith from Duct of Submandibular Gland

- •14.2 Removal of Mucus Cysts

- •Bibliography

- •15. Osseointegrated Implants

- •15.1 Indications

- •15.2 Contraindications

- •15.3 Instruments

- •15.4 Surgical Procedure

- •15.5 Complications

- •15.6 Bone Augmentation Procedures

- •Bibliography

- •16.1 Treatment of Odontogenic Infections

- •16.2 Prophylactic Use of Antibiotics

- •16.3 Osteomyelitis

- •16.4 Actinomycosis

- •Bibliography

- •Subject Index

360 G. Perdikaris, A. Pefanis, E. Giamarellou

antibiotic prophylaxis) did not show a decreased incidence in the group that was administered an antibiotic, we cannot recommend their administration. Some studies showed that the prophylactic administration of antibiotics resulted in fewer, noninfectious complications, such as trismus, pain, edema, and fibrinolytic alveolitis (dry socket). Even so, some of these studies presented methodological planning problems. Two recent reviews do not recommend routine prophylactic administration of antibiotics for surgical extraction of the impacted third molar, concluding that their administration is justified only in very difficult cases, for example when impaction is deep and a large amount of bone has to be removed. Also, according to the recommendations of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (1992) administration of prophylaxis is not recommended for this surgical procedure.

To conclude, it must be emphasized that the administration of antibiotics for a period greater than 24–

48 h after the operation is not considered prophylaxis but therapy. Indications for therapy are limited and include: (a) the presence of edema with pain or sensitivity that suggests cellulitis or an abscess that must absolutely be drained, (b) presence of trismus, unless it is secondary to postoperative edema, hematoma, trauma, (c) presence of purulent exudate, unless the cause was removed and the focal site of infection is far from the airway passages, (d) no improvement of symptoms

48 h later or worsening 36 h or more after surgical procedure, and (e) tachycardia (>100 beats per min) and fever (>38 °C). Fever is not necessarily a symptom of infection, especially in elderly people in whom severe infection may occur without fever.

In conclusion and according to recent data, prophylaxis with antibiotics is recommended for few dental procedures. In these limited cases the antibiotic must be administered shortly before the operation. A second dose is recommended only in the case of extensive and prolonged surgery.

16.3 Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis is a rare complication of odontogenic infections. In most cases it is the result of spread of infection from a dentoalveolar or periodontal abscess, or from the paranasal sinuses, by way of continuity through tissue spaces and planes. It occasionally occurs as a complication of jaw fractures, or as a result of abusive manipulations during surgical procedures. It is classified as acute or chronic osteomyelitis.

In the acute form, which, though rarely, may also be of hematogenous origin, the infection begins in the medullary cavity of the bone. The resulting increase of intrabony pressure leads to a decreased blood supply and spread of the infection, by way of the Haversian canals, to the cortical bone and periosteum. This aggravates the ischemia, resulting in necrosis of the bone. Predisposing factors include compromised host defenses due to compromised local blood supply (Paget’s disease, radiotherapy, bone malignancy, etc.), or systemic disease (e.g., alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, leukemia, AIDS, etc.), and infection from microorganisms with great virulence. In such cases even a periapical abscess may be implicated in osteomyelitis. The mandible, due to decreased vascularity, is involved 6 times more often than the maxilla. The main pathogens are streptococci, Klebsiella spp., Bacteroides spp., and other anaerobic bacteria. Piercing, deep, and constant pain predominates in the clinical presentation in adults, while low or moderate fever, cellulitis, lymphadenitis, or even trismus may also be noted. In the mandible, paresthesia or dysesthesia of the lower lip may accompany the disease. When the disease spreads to the periosteum and the surrounding soft tissues, a firm painful edema of the region is observed, while the tooth becomes loose and there is discharge of pus from the periodontium. Radiographic examination reveals osteolytic or radiolucent regions (Figs. 16.1, 16.2), which sometimes surround a portion of dense bone (sequestrum). Therapy entails combined surgical (incision, drainage, extraction of the tooth, and removal of sequestrum) and pharmaceutical treatment with antibiotics. Antibiotics must be administered intravenously, in large doses, for at least 3–4 days after the fever ceases. Treatment may then continue orally for another 2–4 weeks, depending on the extent of the disease, the causative pathogen, and the clinical response. The antibiotic of choice is penicillin (3 =106 units every 4 hours, i.v.), and in the case of allergy to penicillin, clindamycin is administered (600 mg every 6 h, i.v.). If staphylococcus or another

“difficult” to treat microorganism develops, consultation with an infectious diseases specialist is recommended. In the case of fracture of the mandible, which has occurred over 48 h previously, the possibility of osteomyelitis is great. The patient should be administered antibiotic therapy intravenously as soon as possible, particularly in cases of compound fractures of the mandible.

Chronic osteomyelitis is characterized by a clinical course lasting over a month. It may occur after the acute phase, or it may be a complication of odontogenic infection without a preceding acute phase. The clinical

Chapter 16 Prophylactic and Therapeutic Use of Antibiotics in Dentistry |

361 |

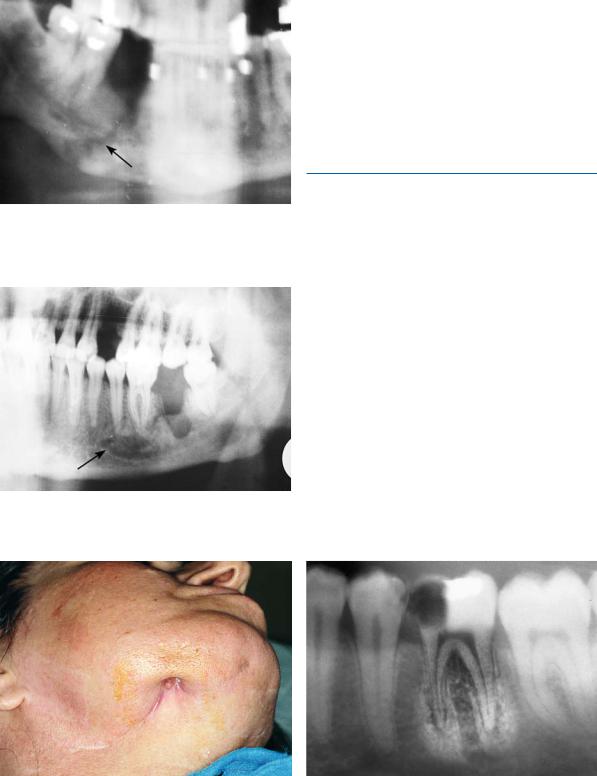

Fig. 16.1. Pathologic (spontaneous) fracture at premolar region of the right side of the mandible as a result of previous osteomyelitis

Fig. 16.2. Chronic osteomyelitis at the molar region and region of first premolar of the left side of the mandible

presentation is milder, with painful exacerbations and discharge of pus, or sinus tracts (Fig. 16.3). Diagnosis is often difficult to make, while scintigraphy with 99mTc helps to reveal latent sites. Generally treatment is the same as that for the acute form, but it lasts a much longer period of time. Hyperbaric oxygen has been used to successfully treat difficult cases. Squamous cell carcinoma is a remote complication of chronic osteomyelitis (incidence ranging from 0.2% to 1.5%).

16.3.1

Sclerosing Osteomyelitis

Other rarer types of osteomyelitis are the chronic focal and chronic diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis.

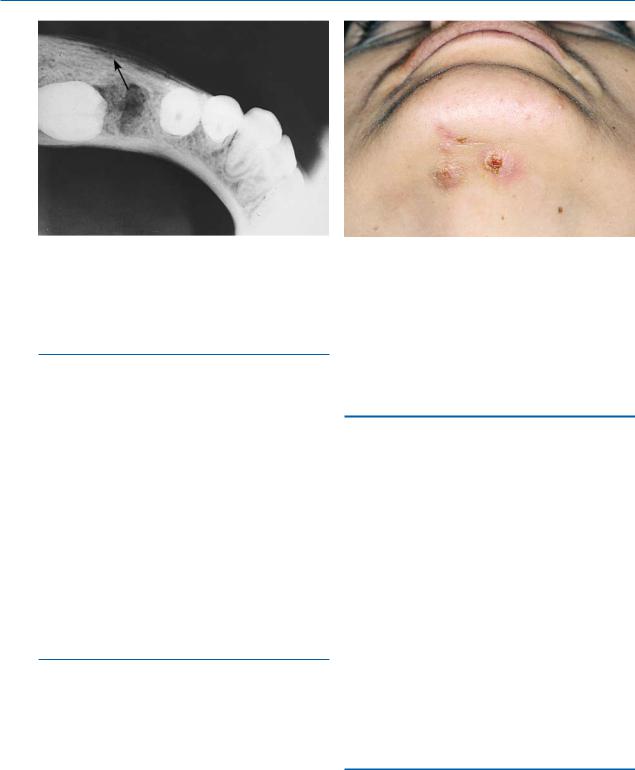

The focal type represents an unusual bone reaction, with normal defense mechanisms, to an infection caused by microorganisms of low virulence. It occurs in persons under 20 years old with significant carious lesions, especially the first molar (Fig. 16.4). Either endodontic therapy or extraction of the tooth is required.

The diffuse form mainly occurs in elderly people, and is exhibited in edentulous areas of the mandible. The symptoms are mild, and include episodes of recurrent pain, edema, and/or trismus. Upon radiographic examination, depending on the phase of the disease, osteolytic or diffuse sclerosing zones at the posterior region of the mandible are observed.

Treatment consists of muscle relaxants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, diazepam, etc., though with questionable results.

Fig. 16.3. Cutaneous sinus secondary to osteomyelitis of the mandible

Fig. 16.4. Periapical radiograph of a case of chronic focal sclerosing osteomyelitis at apical region of the mandibular first molar

362 G. Perdikaris, A. Pefanis, E. Giamarellou

Fig. 16.5. Radiograph of a case of proliferative periostitis in a child, showing localized expansion of the periosteum (onion skin appearance) with peripheral reactive formation of bone

16.3.2

Proliferative Periostitis

Chronic osteomyelitis with proliferative periostitis, formerly known as Garré’s osteomyelitis, is characterized by the formation of new bone beneath the periosteum at the surface of the cortex, which covers an inflammatory area of spongiosa (Fig. 16.5). Common pathogens include staphylococci and streptococci. The lesion is seen in persons less than 30 years of age, usually children, and is characterized by nontender swelling at the inferior border of the mandible. The skin as well as the mucosa has a normal appearance.

Treatment consists of extraction of the tooth, while the administration of antibiotics is a subject of controversy. Remission of the lesion is expected within 2–6 months.

16.3.3 Osteoradionecrosis

Osteoradionecrosis is regarded as a severe disease that is observed after high radiation doses resulting in ischemia of the bone, which leads to necrosis in the case of infection. The cardinal cause of the disease is tooth extraction a short while after the radiotherapy, a period during which the body cannot achieve satisfactory healing. The clinical presentation includes odontalgia and rapid spread of the lesion to a large part of the bone.

Fig. 16.6. Clinical photograph showing actinomycosis. Note draining sinus tracts

Management consists of combined surgical and pharmaceutical treatment, while the use of hyperbaric oxygen is beneficial.

16.4 Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis is usually a chronic bacterial infection, caused by the Gram-positive, anaerobic bacteria Actinomyces israelii. This microorganism lies dormant in the oral cavity and may become activated under certain circumstances. Portals of entry include root canals of infected teeth, postextraction sockets, etc. A hard, slightly painful lesion characterizes the clinical presentation, with reddish overlying skin, on which sinus tracts are often observed (Fig. 16.6). Sulfur granules are found in the pus discharged from the sinus tracts, which are composed of colonies of the microorganism. Either the skin alone or the bone as well may be involved in the infection.

Treatment consists of surgical incision and drainage with excision of sinus tracts, and administration of penicillin for several months (up to a year), depending on the severity of the disease.

Bibliography

Alexandridis C, Kakarantza E, Angelopoulos AP, Kalyvas D (1986) Garre’s osteomyelitis. Review of the literature and report of a case. Odontostomatologike Proodos 40:281–286

Chapter 16 Prophylactic and Therapeutic Use of Antibiotics in Dentistry |

363 |

American Dental Association and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (1997) Advisory statement, antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with total joint replacement. J Am Dent Assoc 128:1004–1008

American Diabetes Association (1999) American Diabetes Association’s standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus (position statement). Diabetes Care 22 (Suppl):532–541

Anonymous (1992) Chemoprophylaxis for infective endocarditis: faith, hope and charity challenged [edit]. Lancet 339(8792):525–526

Baker KA, Fotos PG (1994) The management of odontogenic infections: a rationale for appropriate chemotherapy. Dent Clin North Am 38(4):689–706

Bartkowski SB, Zapala J, Heczko P, Szuta M (1998) Actinomycotic osteomyelitis of the mandible: review of 15 cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 26(1):63–67

Bernier S, Clermont S, Maranda G, Turcotte JY (1995) Osteomyelitis of the jaws. J Can Dent Assoc 61:441–448 Burke S (1961) The effective period of preventive antibiotic

action in experimental incisions and dermal lesions. Surgery 50:161

Cawson RA (1981) Infective endocarditis as a complication of dental treatment. Br Dent J 151:409–414

Cawson RA (1983) The antibiotic prophylaxis of infective endocarditis. Br Dent J 154:253–258

Council on Dental Therapeutics (1985) Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: a committee report of the American Heart Association. J Am Dent Assoc 110:98–100

Council on Dental Therapeutics, American Heart Association (1991) Preventing bacterial endocarditis: a statement for the dental professional. J Am Dent Assoc 122:87–92

Cowper TR (1996) Pharmacologic management of the patient with disorders of the cardiovascular system: infective endocarditis. Dent Clin North Am 40(3):611–647

Dajani AS, Bismo AL, Chung KJ, Durack DT, Freed M, Gerber MA, Karchmer AW, Millard HD, Rahimtoola S, Shulman ST (1990) Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. Recommendations by the American Heart Association. J Am Med Assoc 264(22):2919–2922

Dajani AS, Taubert KA, Wilson W, Bolger AF, Bayer A, Ferrieri P, Gewitz MH, Shulman ST, Nouri S, Newburger JW, Hutto C, Pallasch TJ, Gage TW, Levison ME, Peter G, Zuccaro G Jr (1997) Prevention of bacterial endocarditis: recommendations by the American Heart Association. J Am Med Assoc 277(22):1794–1801

Dickinson GM, Bismo AL (1995) Antimicrobial prophylaxis of infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am 9(3):783–804 Durack DT (1995) Prevention of infective endocarditis.

N Engl J Med 332(1):38–44

Flygare L, Norderyd J, Kubista J, Ohlsson J, Vallo-Christian- sen J, Magnusson B (1997) Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis involving both jaws: report of a case including magnetic resonance correlation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 83(2):300–305

Fowler VG, Durack DT (1994) Infective endocarditis. Curr Opin Cardiol 9:389–400

Gould IM (1990) Current prophylaxis for prevention of infective endocarditis. Br Dent J 168:409–410

Hall EH, Sherman RG, Emmons WW, Naylor GD (1994) Antibacterial prophylaxis. Dent Clin North Am 38(4):707– 718

Hipp BR (1993) The management of third molar teeth. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 5(1):77–85

Hudson JW (1993) Osteomyelitis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51:1294–1301

Kaplan EL (1992) Bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis. Pediatr Ann 21:249–255

Kaye D (1986) Prophylaxis for infective endocarditis: an update. Ann Intern Med 104:419–423

Kitchen R (2004) Postoperative antibiotics. Br Dent J 196(9):515

Kluth EV, Jain PR, Stuchell RN, Frich JC Jr (1988) A study of factors contributing to the development of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws. J Prosthet Dent 59(2):194–201

Knox KW, Hunter N (1991) The role of oral bacteria in the pathogenesis of infective endocarditis. Aust Dent J 36:286–292

Korzemiowski OK (1995) Antibacterial agents in pregnancy. Infect Dis Clin North Am 9(3):639–652

Kwon PH, Laskin DM (1997) Clinician’s manual of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd edn. Quintessence, Chicago, Ill.

Lundeen RC, Barnett DA (1994) Radiolucencies with indistinct or ragged borders. Dent Clin North Am 38(1):83– 112

Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R (1995) Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, New York

Mark AM (1995) Reducing the risk of endocarditis: a review of the AHA guidelines. J Am Dent Assoc 126:1148–1149 Norris LH, Doku HC (1992) Antimicrobial prophylaxis in

oral surgery. Curr Opin Dent 2:85–92

Oh HK, Chambers MS, Garden AS, Wong PF, Martin JW (2004) Risk of osteoradionecrosis after extraction of impacted third molars in irradiated head and neck cancer patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62(2):139–144

Ohlms LA, Jones DT, Schreibstein J, Ferraro N (1993) Sclerosing osteomyelitis of the mandible. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 109(6):1070–1073

Pallasch TJ (1989) A critical appraisal of antibiotic prophylaxis. Int Dent J 39:183–196

Peterson LJ (1990) Antibiotic prophylaxis against wound infections in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 48:617–620

Peterson LJ, Ellis E III, Hupp JR, Tucker MR (1993) Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd edn. Mosby, St. Louis, Mo.

Piecuch JF, Arzadon J, Lieblich SE (1995) Prophylactic antibiotics for third molar surgery: a supportive opinion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53:53–60

Poeschl P, Eckel D, Poeschl E (2004) Postoperative prophylactic antibiotic treatment in third molar surgery – a necessity? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62(1):3–8

Pogrel MA (1993) Infection management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 5(1):127–135

Rahn R, Schneider S, Diehl O, Schafer V, Shah PM (1995) Preventing post-treatment bacteremia. J Am Dent Assoc 126(8):1145–1149

364 G. Perdikaris, A. Pefanis, E. Giamarellou

Recommendations of the American Heart Association (1990) Prevention of bacterial endocarditis. J Am Med Assoc 264:2919–2922

Recommendations from the Endocarditis Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (1990) Antibiotic prophylaxis of infective endocarditis. Br Dent J 169:70–71

Recommendations from the Endocarditis Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (1990) Antibiotic prophylaxis of infective endocarditis. Lancet 335:88–89

Sfikakis P, Giamarellou E et al (1991) Infections and antimicrobial therapy. Litsas, Athens

Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM (1974) A textbook of oral pathology, 3rd edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

Stone HH, Haney BB, Kolb LD, Geheber CE, Hooper CA (1979) Prophylactic and preventive antibiotic therapy: timing, duration and economics. Ann Surg 189:691–699

Swift JQ, Gulden WS (2002) Antibiotic therapy – managing odontogenic infections. Dent Clin North Am 46(4):623– 633

Tan SY, Gill G (1992) Selection of dental procedures for antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis. J Dent 20:375–376

Wahl MJ (1994) Myths of dental-induced endocarditis. Ann Int Med 154:137–144

Weitekamp MR, Caputo GM (1993) Antibiotic prophylaxis: update on common clinical uses. Am Fam Physician 48:597–604

Zeitler DL (1995) Prophylactic antibiotics for third molar surgery: a dissenting opinion. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53:61–64