- •Preface

- •Foreword

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1. Medical History

- •1.1 Congestive Heart Failure

- •1.2 Angina Pectoris

- •1.3 Myocardial Infarction

- •1.4 Rheumatic Heart Disease

- •1.5 Heart Murmur

- •1.6 Congenital Heart Disease

- •1.7 Cardiac Arrhythmia

- •1.8 Prosthetic Heart Valve

- •1.9 Surgically Corrected Heart Disease

- •1.10 Heart Pacemaker

- •1.11 Hypertension

- •1.12 Orthostatic Hypotension

- •1.13 Cerebrovascular Accident

- •1.14 Anemia and Other Blood Diseases

- •1.15 Leukemia

- •1.16 Hemorrhagic Diatheses

- •1.17 Patients Receiving Anticoagulants

- •1.18 Hyperthyroidism

- •1.19 Diabetes Mellitus

- •1.20 Renal Disease

- •1.21 Patients Receiving Corticosteroids

- •1.22 Cushing’s Syndrome

- •1.23 Asthma

- •1.24 Tuberculosis

- •1.25 Infectious Diseases (Hepatitis B, C, and AIDS)

- •1.26 Epilepsy

- •1.27 Diseases of the Skeletal System

- •1.28 Radiotherapy Patients

- •1.29 Allergy

- •1.30 Fainting

- •1.31 Pregnancy

- •Bibliography

- •2.1 Radiographic Assessment

- •2.2 Magnification Technique

- •2.4 Tube Shift Principle

- •2.5 Vertical Transversal Tomography of the Jaw

- •Bibliography

- •3. Principles of Surgery

- •3.1 Sterilization of Instruments

- •3.2 Preparation of Patient

- •3.3 Preparation of Surgeon

- •3.4 Surgical Incisions and Flaps

- •3.5 Types of Flaps

- •3.6 Reflection of the Mucoperiosteum

- •3.7 Suturing

- •Bibliography

- •4.1 Surgical Unit and Handpiece

- •4.2 Bone Burs

- •4.3 Scalpel (Handle and Blade)

- •4.4 Periosteal Elevator

- •4.5 Hemostats

- •4.6 Surgical – Anatomic Forceps

- •4.7 Rongeur Forceps

- •4.8 Bone File

- •4.9 Chisel and Mallet

- •4.10 Needle Holders

- •4.11 Scissors

- •4.12 Towel Clamps

- •4.13 Retractors

- •4.14 Bite Blocks and Mouth Props

- •4.15 Surgical Suction

- •4.16 Irrigation Instruments

- •4.17 Electrosurgical Unit

- •4.18 Binocular Loupes with Light Source

- •4.19 Extraction Forceps

- •4.20 Elevators

- •4.21 Other Types of Elevators

- •4.22 Special Instrument for Removal of Roots

- •4.23 Periapical Curettes

- •4.24 Desmotomes

- •4.25 Sets of Necessary Instruments

- •4.26 Sutures

- •4.27 Needles

- •4.28 Local Hemostatic Drugs

- •4.30 Materials for Tissue Regeneration

- •Bibliography

- •5. Simple Tooth Extraction

- •5.1 Patient Position

- •5.2 Separation of Tooth from Soft Tissues

- •5.3 Extraction Technique Using Tooth Forceps

- •5.4 Extraction Technique Using Root Tip Forceps

- •5.5 Extraction Technique Using Elevator

- •5.6 Postextraction Care of Tooth Socket

- •5.7 Postoperative Instructions

- •Bibliography

- •6. Surgical Tooth Extraction

- •6.1 Indications

- •6.2 Contraindications

- •6.3 Steps of Surgical Extraction

- •6.4 Surgical Extraction of Teeth with Intact Crown

- •6.5 Surgical Extraction of Roots

- •6.6 Surgical Extraction of Root Tips

- •Bibliography

- •7.1 Medical History

- •7.2 Clinical Examination

- •7.3 Radiographic Examination

- •7.4 Indications for Extraction

- •7.5 Appropriate Timing for Removal of Impacted Teeth

- •7.6 Steps of Surgical Procedure

- •7.7 Extraction of Impacted Mandibular Teeth

- •7.8 Extraction of Impacted Maxillary Teeth

- •7.9 Exposure of Impacted Teeth for Orthodontic Treatment

- •Bibliography

- •8.1 Perioperative Complications

- •8.2 Postoperative Complications

- •Bibliography

- •9. Odontogenic Infections

- •9.1 Infections of the Orofacial Region

- •Bibliography

- •10. Preprosthetic Surgery

- •10.1 Hard Tissue Lesions or Abnormalities

- •10.2 Soft Tissue Lesions or Abnormalities

- •Bibliography

- •11.1 Principles for Successful Outcome of Biopsy

- •11.2 Instruments and Materials

- •11.3 Excisional Biopsy

- •11.4 Incisional Biopsy

- •11.5 Aspiration Biopsy

- •11.6 Specimen Care

- •11.7 Exfoliative Cytology

- •11.8 Tolouidine Blue Staining

- •Bibliography

- •12.1 Clinical Presentation

- •12.2 Radiographic Examination

- •12.3 Aspiration of Contents of Cystic Sac

- •12.4 Surgical Technique

- •Bibliography

- •13. Apicoectomy

- •13.1 Indications

- •13.2 Contraindications

- •13.3 Armamentarium

- •13.4 Surgical Technique

- •13.5 Complications

- •Bibliography

- •14.1 Removal of Sialolith from Duct of Submandibular Gland

- •14.2 Removal of Mucus Cysts

- •Bibliography

- •15. Osseointegrated Implants

- •15.1 Indications

- •15.2 Contraindications

- •15.3 Instruments

- •15.4 Surgical Procedure

- •15.5 Complications

- •15.6 Bone Augmentation Procedures

- •Bibliography

- •16.1 Treatment of Odontogenic Infections

- •16.2 Prophylactic Use of Antibiotics

- •16.3 Osteomyelitis

- •16.4 Actinomycosis

- •Bibliography

- •Subject Index

38 F. D. Fragiskos

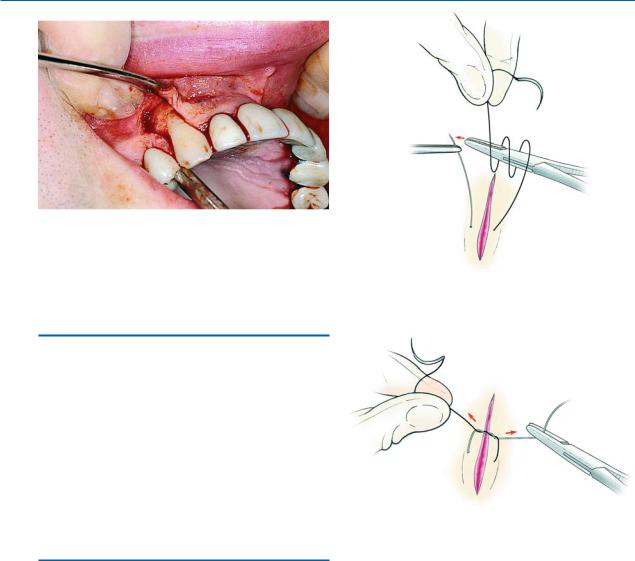

Fig. 3.16. Reflection of the mucoperiosteal flap after incision, with a periosteal elevator, which usually starts from the corner of the horizontal-vertical flap

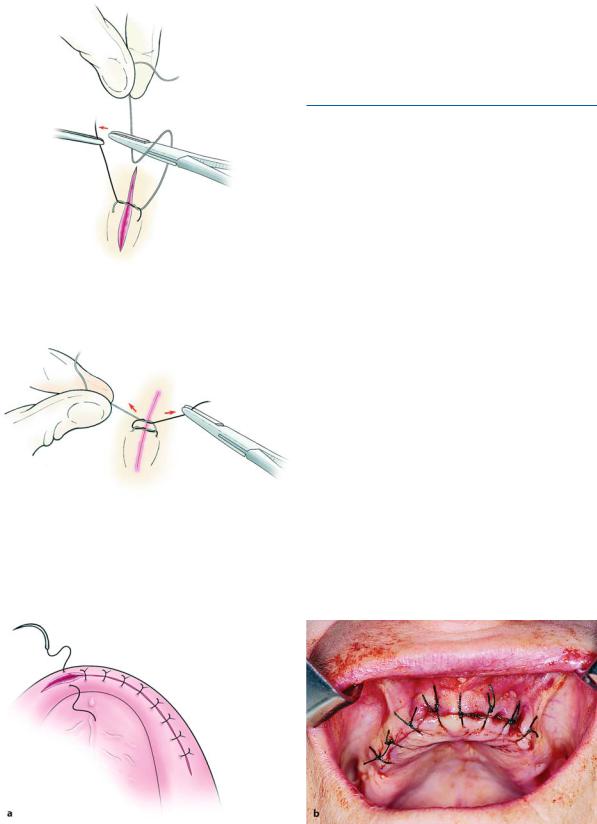

Fig. 3.17. Suturing of wound. Suture is initially wrapped twice around the needle holder

3.6

Reflection of the Mucoperiosteum

Reflection is performed to separate the mucoperiosteal flap from the underlying bone. The elevator is in direct contact with bone and reflection starts at the incision, usually at an angle (Fig. 3.16), and is completed with gentle, steady strokes towards the labial or buccal vestibule, without damaging the tissues. When the attachment between bone and periosteum is strong or if symphysis occurs, then scissors or surgical blades may be used.

3.7 Suturing

Suturing of the surgical wound is necessary, aiming at holding a flap over the wound, reapproximating the wound edges, protecting underlying tissues from infection or other irritating factors, and preventing postoperative hemorrhage. Suturing may also aid in the following:

ΟWhen hemorrhage is present deep in the tissues and ligation is required or for ligation of a large vessel

ΟFor laceration of soft tissues in general

ΟIn cases of severe hemorrhage where the suture holds the hemostatic plug in place

ΟFor infections, after the incision, for stabilization of the rubber drain at the site of incision

ΟFor immobilization of pedicle flaps in their new position, etc.

Fig. 3.18. The two ends of the suture are tightened to create a surgeon’s knot over the wound (double knot)

Stabilization of sutures is achieved with knots, which may be simple or a surgeon’s knot, and are either tied with the fingers of both hands or with the help of the needle holder.

The technique applied for tying knots is as follows: after the needle passes through both wound edges, the suture is pulled, so that the needle-bearing end is longer. Afterwards, the long end of the suture is wrapped around the handle of the needle holder twice (Fig. 3.17). The short end of the suture (which is usually held by the assistant with anatomic forceps) is grasped by the needle holder and pulled through the loops. The suture is then tightened by way of its two ends, thus creating the first double-wrapped knot, which is called a surgeon’s knot (Fig. 3.18). The flap is therefore replaced in the desired position. A single-wrap knot is then created, in the counterclockwise direction, which is named a safety knot (Figs. 3.19, 3.20). The

Chapter 3 Principles of Surgery |

39 |

Fig. 3.19. Safety knot, created by the single wrap of the suture in the counterclockwise direction as opposed to Fig. 3.17

Fig. 3.20. Tightening of the safety knot over the initial surgeon’s knot

knot must always be to the side and never on the incision itself. This makes tightening easier, irritates the wound less, and facilitates cutting and removing the suture.

3.7.1

Suturing Techniques

The main sutures used in oral surgery are the interrupted, continuous, and mattress sutures.

Interrupted Suture. This is the simplest and most frequently used type, and may be used in all surgical procedures of the mouth (Fig. 3.21). The needle enters

2–3 mm away from the margin of the flap (mobile tissue) and exits at the same distance on the opposite side. The two ends of the suture are then tied in a knot and are cut 0.8 cm above the knot. To avoid tearing the flap, the needle must pass through the wound margins one at a time, and be at least 0.5 cm away from the edges. Over-tightening of the suture must also be avoided (risk of tissue necrosis), as well as overlapping of wound edges when positioning the knot. The advantage of the interrupted suture is that when sutures are placed in a row, inadvertent loosening of one or even losing one will not influence the rest.

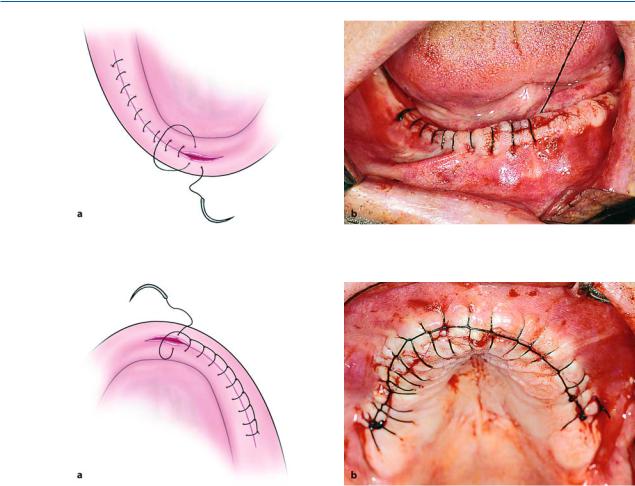

Continuous Suture. This is usually used for the suturing of wounds that are superficial but long, e.g., for recontouring of the alveolar ridge in the maxilla and mandible.

The technique applied is as follows: after passing the needle through both flap margins, an initial knot is made just as in the interrupted suture but only the

Fig. 3.21a,b. Diagrammatic illustration (a) and clinical photograph (b) of simple interrupted sutures. The distance between the sutures is 0.5 cm. The wound margins must coapt without overlapping

40 F. D. Fragiskos

Fig. 3.22a,b. Continuous simple suture. a Diagrammatic illustration. b Clinical photograph

Fig. 3.23 a,b. Continuous locking suture. Wound margin approximation is achieved by successive loops

free end of the suture is cut off. The needle-bearing suture is then used to create successive continuous sutures at the wound margins (Fig. 3.22). The last suture is not tightened, but the loop created actually serves as the free end of the suture. Afterwards, the needlebearing suture is wrapped around the needle holder twice, which grasps the curved suture (first loop), pulling it through the second loop. The two ends are tightened, thus creating the surgeon’s knot.

The continuous locking suture is a variation of the continuous simple suture. This type of suture is created exactly as described above, except that the needle passes through every loop before passing through the tissues, which secures the suture after tightening. Suturing continues with the creation of such loops, which make up parts of a chain along the incision (Fig. 3.23). These loops are positioned on the buccal side of the wound, after being tightened.

The advantage of the continuous suture is that it is quicker and requires fewer knots, so that the wound

margins are not tightened too much, thus avoiding the risk of ischemia of the area. Its only disadvantage is that if the suture is inadvertently cut or loosened, the entire suture becomes loose.

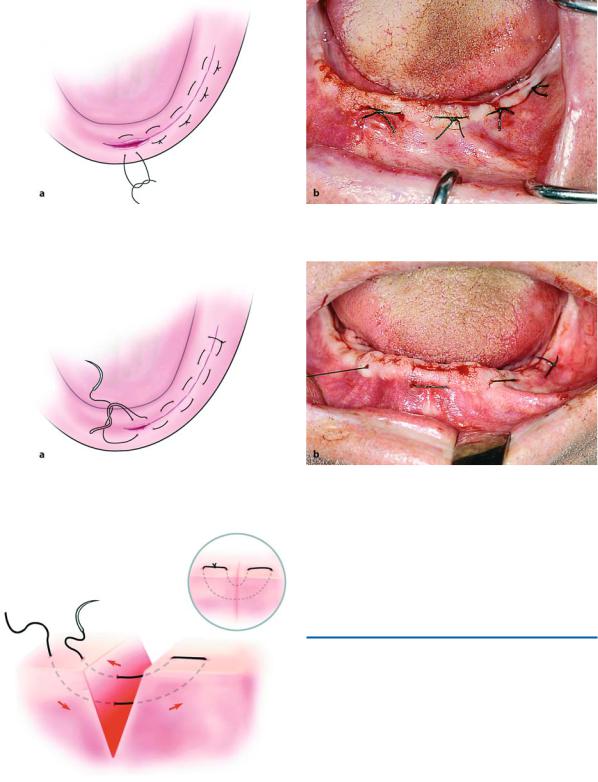

Mattress Suture. This is a special type of suture and is described as horizontal (interrupted and continuous) (Figs. 3.24, 3.25) and vertical (Fig. 3.26). It is indicated in cases where strong and secure reapproximation of wound margins is required. The vertical suture may be used for deep incisions, while the horizontal suture is used in cases which require limiting or closure of soft tissues over osseous cavities, e.g., postextraction tooth sockets. Reinforcement of the mattress suture is achieved with insertion of pieces of a rubber drain.

The technique used for the mattress suture is as follows: in the interrupted suture (horizontal and vertical), the needle passes through the wound margins at a right angle, and the needle always enters and exits

Chapter 3 Principles of Surgery |

41 |

Fig. 3.24 a,b. Horizontal interrupted mattress suture. a Diagrammatic illustration. b Clinical photograph

Fig. 3.25a,b. Horizontal continuous mattress suture. a Diagrammatic illustration. b Clinical photograph. This type of suture is used where wound margins must coapt tightly (tissues with increased tension)

the tissues on the same side. In the horizontal continuous suture, after creating the initial knot, the needle enters and exits the tissues in a winding maze pattern. The final knot is tied in the same fashion as in the continuous simple suture.

Bibliography

Abrams H, Gossett SE, Morgan WJ (1988) A modified flap design in exposing the palatally impacted canine. ASDC J Dent Child 55:285–287

Anavi Y, Gal G, Silfen R, Calderon S (2003) Palatal rotationadvancement flap for delayed repair of oroantral fistula: retrospective evaluation of 63 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 96(5):527–534

Archer WH (1975) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, 5th edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

Fig. 3.26. Vertical mattress suture, used for deep incisions Berwick WA (1966) Alternative method of flap reflection. Br Dent J 121:295–296

42 F. D. Fragiskos

ChinQuee TA, Gosselin D, Millar EP, Stamm JW (1985) Surgical removal of the fully impacted mandibular third molar, the influence of flap design and alveolar bone height on the periodontal status of the second molar. J Periodontol 56:625–630

Council on Dental Materials, Instruments and Equipment (1991) Sterilization required for infection control. J Am Dent Assoc 122:80

Gans BJ (1972) Atlas of oral surgery. Mosby, St Louis, Mo. Giglio JA, Rowland RW, Dalton HP, Laskin DM (1992) Su-

ture removal-induced bacteremia, a possible endocarditis risk. J Am Dent Assoc 123(8):65–66, 69–70

Goldstein M, Boyan BD, Schwartz Z (2002) The palatal advanced flap: a pedicle flap for primary coverage of immediately placed implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 13(6):644–650

Groves BJ, Moore JR (1970) The periodontal implications of flap design in lower third molar extractions. Dent Practitioner Dent Rec 20:297–304

Hastreiter RJ, Molinari JA, Falken MC, Roesch MH, Gleason MJ, Merchant VA (1991) Instrument sterilization procedures. Effectiveness of dental office. J Am Dent Assoc 122:51–56

Hayward JR (1976) Oral surgery. Thomas, Springfield, Ill. Howe GL (1996) The extraction of teeth, 2nd edn. Wright,

Oxford

Howe GL (1997) Minor oral surgery, 3rd edn. Wright, Oxford

Keith DA (1992) Atlas of oral and maxillofacial surgery. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

Kincaid LC (1976) Flap design for exposing a labially impacted canine. J Oral Surg 34:270–271

Koerner KR (1994) The removal of impacted third molars. Principles and procedures. Dent Clin North Am 38:255– 278

Koerner KR, Tilt LV, Johnson KR (1994) Color atlas of minor oral surgery. Mosby-Wolfe, London

Kramper BJ, Kaminski EJ, Osetek EM, Heuer MA (1984) A comparative study of the wound healing of three types of flap design used in periapical surgery. J Endodon 10:17–25

Kruger E (1979) Oral surgery. Laterre, Athens

Kruger GO (1984) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, 6th edn. Mosby, St Louis, Mo.

Kwon PH, Laskin DM (1997) Clinician’s manual of oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd edn. Quintessence, Chicago, Ill.

La Scala G, del Mar Lleo M (1990) Sutures in dentistry. Traditional and PTFE materials. Dent Cadmos 58:54–58, 61 Laskin DM (1985) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, vol 2.

Mosby, St Louis, Mo.

Leonard MS (1992) Removing third molars. A review for the general practitioner. J Am Dent Assoc 123:77–86

Lilly GE, Salem JE, Armstrong JH, Cutcher JL (1969) Reaction of oral tissues to suture materials. Part III. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 28:432–438

Macht SD, Krizek TJ (1978) Sutures and suturing – current concepts. J Oral Surg 36:710–712

Magnus WW, Castner DV, Hiatt WR (1972) An alternate method of flap reflection for mandibular third molars. Mil Med 137:232–233

Martis CS (1990) Oral and maxillofacial surgery, vol 1. Athens

McGowan DA (1989) An atlas of minor oral surgery. Principles and practice. Dunitz-Mosby, St Louis, Mo.

Meyer RD, Reid EL, Antonini CJ, Taylor JT (1989) Fabrication of a teaching aid for dental soft tissue management and suturing. J Am Dent Assoc 118(3):345–346

Miller CH (1991) Sterilization. Disciplined microbial control. Dent Clin North Am 35(2):339–355

Miller CH (1993) Cleaning, sterilization, and disinfection: basics of microbial killing for infection control. J Am Dent Assoc 124:48–56

Peacock EE Jr (1984) Wound repair, 3rd edn. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.

Peterson LJ, Ellis E III, Hupp JR, Tucker MR (1993) Contemporary oral and maxillofacial surgery, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis, Mo.

Roberts DH, Sowray JH (1987) Local anesthesia in dentistry. Wright, Bristol

Sailer HF, Pajarola GF (1999) Oral surgery for the general dentist. Thieme, Stuttgart

Salins PC, Kishore SK (1996) Anteriorly based palatal flap for closure of large oroantral fistula. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 82:253–256

Stavrou E, Alexandridis K, Thalassinos G (1983) Basic steps in creating mucoperiosteal flaps in oral surgery. Hell Stomatol Chron 27(2):21–24

Stephens RJ, App GR, Foreman DW (1983) Periodontal evaluation of two mucoperiosteal flaps used in removing impacted mandibular third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 41:719–724

Suarez-Cunqueiro MM, Gutwald R, Reichman J, OteroCepeda XL, Schmelzeisen R (2003) Marginal flap versus paramarginal flap in impacted third molar surgery: prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 95(4):403–408

Tarnow DP (1986) Semilunar coronally repositioned flap. J Clin Periodontol 13:182–185

Thoma KH (1969) Oral surgery, vol 1, 5th edn. Mosby, St Louis, Mo.

Waite DE (1987) Textbook of practical oral and maxillofacial surgery, 3rd edn. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, Pa.

Winstanley RP (1985) The use of sutures in the mouth. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 23:381–385