Money, Banking, and International Finance ( PDFDrive )

.pdf

Money, Banking, and International Finance

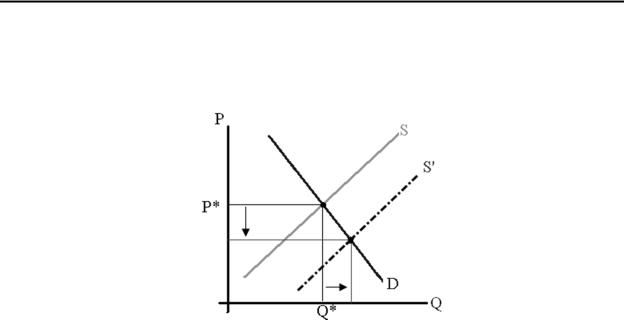

function increases, shifting rightward, decreasing the market price. Thus, the U.S. dollar depreciates while Malaysian ringgit appreciates.

Price of U.S. dollar

Ringgits per U.S. dollar

Quantity of U.S. dollars

Figure 6. The Federal Reserve increases the supply of dollars on the exchange market

A central bank holds foreign currencies. If a central bank wants to strengthen its currency, it must buy its currency using a foreign currency. Consequently, a central bank’s cache of foreign currencies would decrease. If a central bank weakens its currency, subsequently, it buys foreign currencies using its own currency. Hence, a central bank accumulates more foreign currencies. The key is scarcity. If the exchange market has little of a country’s currency, then the currency becomes more scarce. Consequently, investors, central banks, and people value it more.

If investors believe a currency will depreciate, then their beliefs become self-fulfilling prophecies. For example, we depict the international currency market for U.S. dollars in Figure 7. Unfortunately, the investors believe the U.S. dollar will depreciate. Consequently, the investors reduce their demand for U.S. dollars and shift the demand leftward, decreasing the exchange rate. Thus, the U.S. dollar depreciates while the euro appreciates. Investors’ beliefs turned into reality. In a worst-case scenario, a depreciating currency triggers a capital flight. International investors withdraw their investments from a foreign country, collapsing its currency and creating a severe financial crisis for the country.

Supply and demand analysis could be ambiguous in some cases. For example, Malaysia’s GDP grows faster than U.S. GDP. Malaysian citizens experience growing incomes and would increase their demand for all products, including imports. Thus, Malaysian citizens increase their demand for U.S. dollars, increasing the supply of ringgits on the currency exchange market. U.S. dollar appreciates while the ringgit depreciates. A rapidly growing country experiences greater inflation, which causes its currency to depreciate. However, a prospering country tends to have higher interest rates, which has the opposite effect on the market.

201

Kenneth R. Szulczyk

Price of U.S. dollar

Euros per U.S. dollar

Quantity of U.S. dollars

Figure 7. Investors decrease their demand for U.S. dollars

In the real world, many factors influence exchange rates. A country could impose trade barriers like tariffs and quotas. A tariff is a tax on imports, while a quota limits the quantity of imports. Both trade barriers reduce a country’s imports. Furthermore, some countries could impose strict regulations. Extensive regulations and taxes reduce trade and financial capital flows. Finally, investors’ expectations and uncertainty can impact trade flows.

Fixed Exchange Rates

Central banks in several countries established a fixed exchange rate with a strong currency, such as the U.S. dollar or euro. A fixed exchange rate is a pegged exchange rate. Usually a government or central bank established a currency board that maintains the exchange rate. For example, Argentina, Bermuda, and Hong Kong pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar while Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, and Estonia fixed their currencies to the euro. Furthermore, a central bank must hold a cache of currency reserves to buy or sell currencies to balance its currency flows that maintain the fixed exchange rate.

We expand the supply and demand analysis to include a fixed exchange. A central bank does not specify an exact price, but it allows its currency to fluctuate within a band, depicted in Figure 8. Consequently, a central bank allows the market to change the exchange rate within the band. If the exchange rate falls outside of the band, then the central bank must intervene in the currency market to return the exchange rate back within the band. Thus, a central bank requires a cache of currency reserves.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) pegged its currency exchange rate to U.S. dollars, where one U.S. dollar equals three dirhams. As an illustration, the international investors reduce their demand for the dirhams, decreasing the exchange rate below the band. Consequently, the UAE central bank must buy dirhams from the currency exchange market. It exchanges U.S. dollars or

202

Money, Banking, and International Finance

euros for dirhams, decreasing the supply function and shifting it leftward. Thus, the exchange rate returns within the band.

Price of Dirhams ($s per dirham)

Quantity of Dirhams

Figure 8. The Currency Exchange Market for Dirhams

Price of Dirhams ($s per dirham)

Quantity of Dirhams

Figure 9. A central bank intervenes in the currency market

Two important terms are associated with a pegged exchange rate. If a central bank allows its currency to appreciate permanently outside the band, then we call it a revaluation. A central bank may not strengthen its currency too often because the central bank accumulates capital from the surplus inflow. On the other hand, if the central bank allows the currency to depreciate

203

Kenneth R. Szulczyk

permanently outside the band, subsequently, we call it a devaluation. A country experiences a continuous outflow of capital, and the central bank does not have the reserves to buy its currency from the currency exchange markets. Thus, this country could devalue its currency to reduce its balance-of-payments deficit.

Devaluation can trigger capital flight and a severe financial crisis. Moreover, devaluation lessens the investors’ faith in a government's leaders. For example, international investment fund managers invested approximately $45 billion in Mexico to earn the higher interest rate before 1994. Influx of foreign capital appreciated the Mexican peso, which reduced exports and boosted imports. Furthermore, Mexicans reduced their savings and increased their consumption. Unfortunately, the Mexican government could not finance the large trade deficits as it depleted its reserve funds. Then Mexico devalued the peso on December 20, 1994, triggering capital flight. International investors cashed in their Mexican stocks and bonds and began massive capital withdrawals from Mexico. Peso depreciated at least 40% by January 1995. Unfortunately, capital flight can lead to a contagion, when investors question their investments in other countries, spreading the crisis. The Bank of International Settlements and International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailed out Mexico with a $53 billion package, which stabilized the world's financial markets.

For another example, the investors were attracted to the Asian countries because their economies grew rapidly, and they could earn high investment returns. The Thai government pegged the baht to the U.S. dollar. Then the Thai government devalued the baht on July 2, 1997. Next, the investors panicked and suddenly withdrew their investments from Thailand. Subsequently, the crisis became a contagion, spreading to Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and South Korea as investors questioned their investment in those countries. Crisis continued to spread until it reached Russia and Brazil. Unfortunately, all the countries experienced large devaluations of their currencies. Companies and corporations that accepted loans denominated in foreign currencies quickly defaulted. Once their home currency began depreciating, they could not afford to repay their foreign debt.

The IMF bailed out Indonesia, South Korea, and Thailand. As part of loan conditions, the countries imposed austerity. Austerity is the government must reduce government spending and/or raise taxes. The IMF also wanted the countries to raise the interest rates to stop capital flight. International investors are attracted to high interest rates. Unfortunately, Thailand and Indonesia experienced declines of 20% or more of their industrial production. Austerity in this case worsens their economies. According to Keynesian economics, during a downturn in an economy, a government must increase spending and/or reduce taxes to boost the economy. Unfortunately, austerity does the opposite, which slows down the economy. Furthermore, for a country to boost its interest rates, a central bank must reduce the money supply, which again, slows down the economy, increasing the severity of the crisis.

The Rule of Incompatible Trinity states a central bank can only control two out of the three variables: Fixed exchange rate, free international flow of capital, and independent monetary policy. For example, Hong Kong allows the free flow of capital and pegs the exchange rate to the U.S. dollar. Thus, it cannot support an independent monetary policy because the central bank must maintain the fixed exchange rate. On the other hand, China and India impose capital

204

Money, Banking, and International Finance

controls that prevent investors withdrawing from their economies. Consequently, both countries could impose a fixed exchange rate while the central bank can pursue an independent monetary policy.

Key Terms |

|

foreign-currency exchange market |

pegged exchange rate |

hedging |

revaluation |

speculation |

devaluation |

arbitrage |

capital flight |

cross rate |

austerity |

intermarket arbitrage |

Rule of Incompatible Trinity |

fixed exchange rate |

|

Chapter Questions

1.United Arab Emirates uses the dirham as its currency. How much does a Pepsi costs in dirhams if Pepsi costs $0.75 with an exchange rate $1 = 3 dirhams?

2.Please calculate the cross-rate exchange rate for the convertible mark (KM) and U.S. dollar for the following exchange rates:

KM to euros: KM 2 / 1 €

Euros to U.S. dollars: € 0.714 / 1$

3.A trader at Citibank has 500,000 Bosnian convertible marks (KM) and observes the following exchange rates:

Citibank: |

€ 1 /2 KM |

National Westminster: |

kuna 100 / € 1 |

Deutsche Bank |

kuna: 46 / 1 KM |

Please note the kuna is the Croatia's currency. Please calculate the cross rate to determine if arbitrage exists. If intermarket arbitrage exists, how much profit could the Citibank trader earn?

4.As you examine the demand and supply of U.S. dollars in a market, where does the supply of U.S. dollars originate from?

5.Please draw a supply and demand function for Mexican pesos. What would happen to the market if the 2008 Financial Crisis causes Americans to reduce their demand for Mexican made products?

205

Kenneth R. Szulczyk

6.Please draw the demand and supply for the U.S. dollar exchange market with the euro as the other currency. How can the Federal Reserve strengthen the U.S. dollar relative to the euro? Could the European Central Bank oppose this?

7.The Federal Reserve reduces the U.S. interest rate to jump-start the U.S. economy. What would happen to the U.S. dollar exchange market if the Fed pursues a low “real” interest rate policy?

8.Please draw the international market for the Uzbek som. The Uzbek government established a fixed exchange rate between the Uzbek som and the U.S. dollar. What would happen if people have less demand for this currency? What should the Uzbek government do to maintain the pegged exchange rate?

9.The Japanese government has a government debt to GDP ratio approximately 200%. The Japanese government and the Japanese citizens hold most of the debt. Does Japan have a risk of capital flight if investors believe the Japanese government will default on its debt?

206

17.International Parity Conditions

Supply and demand analysis allows investors and economists to predict directional changes in a country's exchange rate. Unfortunately, the analysis cannot answer quantitative changes. Consequently, this chapter builds on the supply and demand analysis and uses several theories to predict quantitative changes in a country's currency exchange rates. We will study the random walk, Purchasing Power Parity Theory, the Relative Purchasing Parity Theory, Interest Rate Parity Theorem, and International Fisher Effect. Furthermore, we study the Big Mac Index from the Economist because we can easily determine whether a country's currency is over or undervalued relative to the U.S. dollar. Then we can predict which direction the exchange rate should move over time.

A Random Walk

Currency market exchange rates could exhibit a random walk in the short run. Statisticians define a random walk whose current value is the previous period’s value plus a random disturbance. We show a random walk in Equation 1. Value of the spot exchange rate today is st, which equals yesterday's exchange rate, st-1, plus a random disturbance, et. We assume the random disturbance is distributed normally with a mean of zero with a fixed standard deviation. For example, if the U.S. dollar-euro exchange rate equals $1.3 per euro today, then we expect the exchange rate to be $1.3 per euro tomorrow plus a random fluctuation.

= |

+ |

(1) |

We show the monthly U.S. dollar-euro exchange rate in Figure 1. A random walk has an unique characteristic – the variable drifts in a particular direction before changing direction. If we take a first difference of the exchange rate, then the difference equals the random disturbance, illustrated in Equation 2. A first difference is we take today's spot exchange rate and subtract the previous period, which is monthly for our case. We show the first difference for the U.S dollar-euro exchange rate in Figure 2. Line indicates the randomness of the exchange rate, but it is not completely random. Moreover, statistical tests indicate the U.S. dollar-euro exchange rate is almost a random walk1. However, these statistical tests are beyond the scope of this book.

− = |

(2) |

Although currency exchange rates exhibit a random walk in the short run, economists and financial analysts use several theories to explain long-run movements.

1 The U.S. dollar-euro exchange rate has the structure, |

|

|

|

, where p1 is close to one |

while p2 has a significant second lag. Unfortunately, this is |

not an anomaly. Many exchange rates exhibit this |

|||

= |

+ |

+ |

|

|

structure or exhibit a pure random walk.

207

Kenneth R. Szulczyk

Figure 1. The U.S. dollar-per euro exchange rate

Figure 2. First difference of the U.S. dollar per euro exchange rate

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) Theory

Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) Theory is based on the Law of One Price. Goods and products denominated in the same currency should have the identical price between markets

208

Money, Banking, and International Finance

after adjusting for transportation costs. If a price difference exists between two markets, then arbitrage is possible. Traders would buy products from the low-price market and sell products to the expensive market. Consequently, prices would converge to one price across all markets as traders shifted supply from the low-price market to the high-price market. The high prices would fall while the low prices would rise over time.

Price could differ between markets because the price difference reflects the transportation costs of shipping the product from one market to another. Nevertheless, the Purchasing Power Parity helps predict changes in exchange rates. For example, the petroleum price equals $90 per barrel in the United States and 850 pesos per barrel in Mexico. Implied exchange rate equals one U.S. dollar equals 9.444 Mexican pesos (or pesos 850 ÷ $90). If the actual exchange rate is $1 = 10 Mexican pesos, then the U.S. dollar is overvalued while the peso is undervalued. Actual exchange rate means a $90 per barrel of petroleum costs $85 per barrel in Mexico. Consequently, the traders could buy petroleum from Mexico, and they ship and sell petroleum to United States. Over time, the petroleum price rises in Mexico because the traders reduced petroleum supply while the petroleum price decreases in United States because the petroleum supply increases. Eventually, arbitrage stops, when the prices converge between both countries. Thus, Purchasing Power Parity estimates the equilibrium exchange rate.

Economists expand the Purchasing Power Parity to include many products in a society. Then economists can compare a basket of goods of one country to another country. Consumer Price Index (CPI) is a measure of a basket of goods in the United States. The CPI is an aggregate measure of prices, and economists use it to measure inflation. The Absolute Purchasing Power Parity states the foreign exchange rate between two currencies is the ratio of the two countries’ general price levels. We define the notation as:

Domestic price level for home country equals Pd. |

|

Foreign price level equals Pf. |

|

Spot exchange rate between countries equals S. |

|

We define the absolute PPP exchange rate by Equation 3. |

|

S = Pf |

(3) |

Pd |

|

For example, the CPI for the United States equals $755.3 while the CPI for Switzerland is 1,241.2 francs. Thus, the absolute PPP predicts the exchange rate should be 1.64 francs per U.S. dollar that we calculated in Equation 4.

|

Pf |

|

1,241.2 francs |

1.64 francs |

|

|

|

S = |

|

= |

|

= |

|

$1 |

(4) |

Pd |

$755.3 |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

209 |

Kenneth R. Szulczyk

If the spot exchange rate is 1.4 francs per $1, subsequently, traders use arbitrage. The CPI in the United States in francs is 1,057.42 (or $755.3 × 1.4 francs per $1), which is smaller than the CPI of Switzerland. Thus, traders could profit by purchasing a basket of goods from United States and selling it to Switzerland. Thus, they potentially earn 1,241.20 – 1,057.42 = 183.78 francs per basket of goods.

The Economist publishes the Big Mac Index, based on the Purchasing Power Parity. McDonald’s sells Big Macs in over 123 countries around the world. The Big Mac requires many ingredients like beef, buns, lettuce, tomatoes, onions, and its special sauce. Furthermore, restaurants pay labor, retail space, and utilities like water, electricity, and natural gas. Consequently, a Big Mac's price correlates to the prices of its inputs, and the inputs represent a variety of sectors in a country’s economy. Thus, the price of a Big Mac reflects a country’s PPP that we show for 10 countries in Table 1. Finally, some analysts designed a Starbuck's Index similarly to the Big Mac Index.

Table 1. The Economist’s Big Mac Index for 2005

Country |

Big Mac Price |

Implied PPP |

Exchange Rate |

Over Valued (+) |

|

U.S. $ |

currency per U.S. $ |

currency per U.S. $ |

Under Valued (-) |

United States |

4.33 |

- |

- |

- |

Argentina |

4.16 |

4.39 |

4.57 |

-4% |

Australia |

4.68 |

1.05 |

0.97 |

+8% |

China |

2.45 |

3.62 |

6.39 |

-43% |

Europe (Eurozone) |

4.34 |

1.21 |

1.21 |

0% |

Japan |

4.09 |

73.95 |

78.22 |

-5% |

Malaysia |

2.33 |

1.71 |

3.17 |

-46% |

Mexico |

2.70 |

8.55 |

13.69 |

-38% |

Russia |

2.29 |

17.33 |

32.77 |

-47% |

Switzerland |

6.56 |

1.05 |

0.99 |

+52 |

Venezuela |

7.92 |

7.86 |

4.29 |

+83% |

Source: The Economist Big Mac Index. July 2012. Available from http://www.scribd.com/doc/102253973/Big- Mac-Index-July-2012 (Access date 9/28/2012).

The Big Mac price is denominated in U.S. dollars, and we convert it to U.S. dollars using the spot exchange rate. Moreover, the implied PPP is the ratio of a Big Mac's price in the foreign currency divided by the average U.S. price in dollars. Finally, the exchange rate is the spot exchange rate on July 25, 2012. Consequently, we could earn a profit by buying Big Macs in Malaysia for $2.33 and selling the hamburgers in the United States for $4.33. However, we must pay transportation costs and would experience problems bringing numerous hamburgers through customs. Furthermore, the Big Macs would not be fresh, and they would quickly spoil before they reached their destination.

We can calculate the Big Mac easily. For example, the price of a Big Mac in Malaysia averaged 7.4 ringgits, which is the spot exchange rate multiplied by the Big Mac’s price in U.S. dollars (or 2.33 × 3.17). If the costs are identical for both Malaysia and the United States, then the implied PPP value is the Big Mac’s price in ringgits divided by the U.S. price, which equals

210