- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

354 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

fairly restricted – mostly open-mouthed pots with splayed rims and rounded, fl attened, or slightly thickened lips; and broad pans with upright sides.These vessels were rarely decorated; ornaments, for the most part haphazard notches, appear only in the late Middle Bronze Age, when obsidian temper disappears. Another distinct surface treatment is roughening of the neck with a comb, which was dragged across the surface at a slight diagonal. This effect, too, appears towards the end of the period and foreshadows ornamentation in the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. No examples of Bedeni ware were found, though a few fragments in the lower levels resemble Martkopi. Ceramics of the developed Trialeti were found from the upper levels of both sites. A large, black burnished jar from Didi Gora Level 11 is finely ornamented with a comb stamped and grooved zigzag design.

The Brili Cemetery

Before we turn to other matters, the extraordinary material, largely unpublished, found at the Brili cemetery – located in west Georgia, in the Upper Racha region – deserves attention. Brili was a place of considerable importance to the local communities who used it intermittently as a burial ground for about 2,000 years from the early second millennium BC to the fourth century AD. Investigations led by Germane Gobedzhishvili more than seventy years ago opened more than 200 tombs at Brili, which is characterised by a diversity of belief systems and mortuary practices – earthen pit tombs, stone cist tombs, and cremation platforms.132

Most attention has been has been directed to the ceremonial weapons and other items from stone cist Tomb 12, which provides yet another glimpse of the pomp and splendour displayed by leaders of the Bronze Age. Like special items from other burials of the Middle Bronze Age, the Brili metalwork was manufactured for display.These elaborate objects were an ostentatious expression of authority and power, which leaders of the day used for maximum effect.

A recent study described Tomb 12 as a double-storeyed stone cist with a large septal stone dividing the lower chamber from the upper one.133 It is not clear how many individuals were buried in the tomb, possibly as many as five. Their bones were scattered across the tomb, except for those of two individuals.The primary burial comprised the articulated skeleton of a middle-aged or young male lying on his left side in a highly contracted position with the head

132The total number is unclear, suffice to say that the majority (some 200) were earthen pits. For the original preliminary report see Gobedzhishvili 1959. Other interpretative studies can be found in Krupnov 1951; Gogadze and Pantskhava 1989; Miron and Orthmann 1995; Motzenbäcker 1996; Pantskhava et al. 2001.

133Pantskhava et al. 2012. Earthen pit 31, as yet unpublished, is reported as having similar material to Tomb 12.

The Middle Bronze Age II (2000/1900–1700 BC) |

355 |

pointing south and hands in front of his face.Another skeleton, also contracted, was found on its right side, with fragments of black pottery, a pair of pins, and many beads found beneath the skull. The original diaries also reported that the floor of the lower chamber was decorated with countless minute beads made from a sky-blue paste (faience?), but regrettably they were not properly documented.

The distribution of grave goods within the tombs also displayed an intentional pattern, though its meaning is unclear. Bronze pins, axes, and daggers lined the southern and northern walls of the chamber, whereas most other items, including ram-headed pendants, spearheads, socketed axes, and daggers, were scattered across the floor.Three pairs of bronze bracelets, a pair of temple rings, two fragments of a silver sheet, and several jade beads were placed in the centre part of the chamber floor.

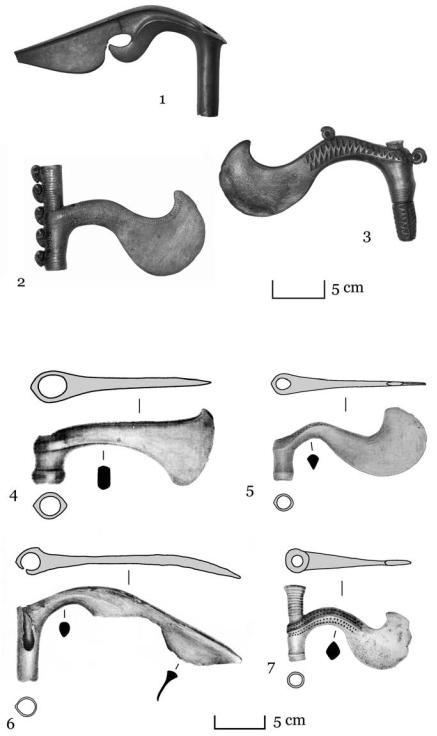

Amongst the most precious items are a number of sinuous axes of exaggerated form, some elaborately decorated, which most probably functioned as ceremonial objects (Figure 7.23(1–3)). Stylistically, they compare well with items from the northern Caucasus, especially those recovered from the Faskau cemetery (Figure 7.23(4–7)), near Galiat in the central northern Caucasus.134 There is little agreement on their date, other than that they belong to the second millennium BC and lie somewhere between the curved axes from Early Bronze Age Sachkhere and the ornamented examples from Early Iron Koban. Some assign the Brili axes to the Middle Bronze Age (1800–1600 BC), largely on the basis of their long tubular socket and exaggerated forms, whereas other researchers believe they are better accommodated in the Late Bronze Age (1300–1250 BC).135 Overall, the higher date seems to me the most compelling, though without a single radiocarbon date we are at the mercy of artefact typology.

A high sense of decorativeness is a key feature of the Brili axes. One example with an up-swung, curved blade has five ram heads running down the back of its tubular socket, which is decorated with horizontal incisions (Figure 7.23(2)). Rows of incised motifs are also applied to the upper edge of the blade.Another axe bears an excised pattern of triangles and two ram heads – one placed at the back of the socket and another attached to the upper edge. Of these items, the one with curved downturned blade (Figure 7.23(1)) is most likely a ceremonial standard and has a close parallel at Faskau. Other sinuous axes from Brili that have no decoration have been loosely compared to items from Mestia (in upper Svanetia) and Tli (Georgian Tlia).136

134Uvarova 1900; Krupnov 1951. For east European connections with Faskau see Gimbutas 1965: 66.

135Most studies prefer an early to mid-second millennium date, though Pantskhava et al. (2012) maintain a low chronology in the last centuries of the second millennium.

136Pantskhava et al. 2012: 40.

356 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

Figure 7.23. Ceremonial standards (1–3) Brili (photographs A. Sagona); (4–7) Faksau (after Motzenbäcker 1996).