- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

320 The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order

the Royal Graves at Ur.48 Underneath the paws are tiny holes that originally fastened the figurine to a support, also suggested by the long tail that extends below the paws so that the figurine cannot stand on all four feet. Other items included a leather shield, obsidian arrowheads, 40 ceramic vessels, and 465 astragalus bones of sheep.

Not all the Bedeni barrows were monumental and lavish in their inventory. The barrow at Abanoskhevi in Shida Kartli was roofed in wood and paved with stones, and had thirty-eight gold beads amongst other gifts.49 But those tumuli located in the Kvemo Kartli lowlands, such as those at Kramebi (near Gurdzhaani), Gadachrili-Gora, and at Shulaveri were modest by comparison. Outliers are also found at Ilto, where they have been associated with the lower settlement, and variants have been reported in Dagestan and the Karabakh region.50 These were much smaller tombs (ca. 30 m in diameter and 1–1.5 m high), distinguished by a square shaft covered with a mound of earth and stone. In two cases, the deceased were placed on their left sides in a flexed position. They were accompanied by black burnished ceramic vessels, copper dagger blades, four-sided needles, hollow-based obsidian, and flint projectile points, grooved chisels, fl at axes, and socketed axes with a fl anged blade.

Bedeni Settlements

Berikldeebi Village

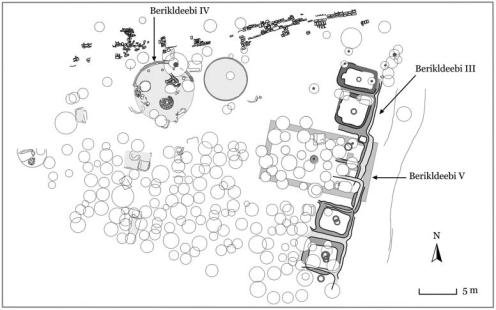

Berikldeebi Period III affords a rare glimpse of a Bedeni settlement.51 The village spread across the entire site (ca. 110 x 80 m) and was distinguished by an ashy and pebble matrix, never deeper than about 1 m. Dzhavakhishvili distinguished two levels: a lower one with seven building phases, and the uppermost one with numerous pits (Figure 7.10).A bewildering array of more than 200 pits, an astonishing number by any reckoning, punctuates most of the extent of the site. Many of these pits cut through the two earlier periods creating a palimpsest of re-occupation that was taxing to disentangle. Remains of a stone perimeter wall, about 15 m in length, suggest there was a need for security. Architectural evidence is fragmentary – patches of clay-plastered and beaten earthen floors, pebble foundations, pieces of clay with post-and-wattle impressions – but enough to delineate fourteen houses. Owing to the quantity of ashy material, Dzhavakhishvili made the perceptive observation that the

48Abramishvili 2010: 169.

49Gogadze 1972; Dzhaparidze 1975; Gogochuri 2008: 39–41.

50Ilto (Dedabrishvili 1969: 60), Dagestan (Gadzhiev 1983: fig. 1.11), and Karabakh (Kushnareva 1954: fig. 1.1). See also Dzhaparidze 1994: 80.

51I would like to thank Mindia Jalabadze for giving me access to the Berikldeebi archives and material. Kipiani 1997; Dshawachischwili 1998; Jalabadze 2014.

Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (2500–2000 BC) |

321 |

Figure 7.10. Berikldeebi. Plan of site showing key cultural levels III–V and their features (drawn by M. Hutson and C. Sagona, original plan courtesy M. Jalabadze).

Bedeni houses were possibly burnt as part of ritual process, a practice that has been postulated for other cultural horizons elsewhere.52

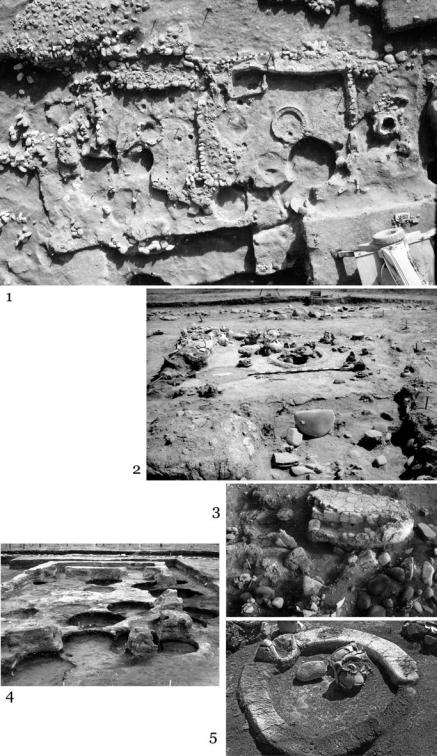

The basic plan of the earliest Bedeni houses (Phase 1) is clear and recalls that of the Kura-Araxes: a rectangular main room with a central fixed, baked-clay hearth, and an attached anteroom (Figures 7.10 and 7.11). Hearths, too, have familiar features.They can be up to 1.75 m in diameter (Building 14) and bear decoration. Small bowl-like projections attached to the hearth of Building 12 are a novel feature. Later houses can be almost square with slightly rounded corners, and usually have an anteroom.

Remains of a large, multi-roomed rectangular structure (18 x 6 m) were found in Level 3. Facing west and built directly onto the ground, its rear almost touched the perimeter wall.Although structurally unified, these four rooms in a row were essentially independent buildings – Buildings 2, 3, 4, and 5 – that shared a back and a party wall. Supported by a framework of timber posts, the large structure had a common roof, shared by each room, which had sturdy posts set in the corners for reinforcement.

Level 5 contained at least two buildings (nos. 7 and 8), which also formed a unified structure, having common back and side walls. Both are similar in plan, approximating a square (5 x 5 m), and each had a bench (25 cm high and 50 cm wide) that ran along three sides of the wall, a feature redolent of the

52 Stevanović 1997; Sagona and Zimansky 2009: 88.

Figure 7.11. Berikldeebi: (1) Bedeni houses 3, 4 and 5; (2) Bedeni House 7; (3) Platform 10; (4) Bedeni pits dug into LevelV ‘temple’; (5) hearth in Building 8; (nos. 1–3, 5, courtesy M. Jalabadze; no. 4 photograph A. Sagona).

322

Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (2500–2000 BC) |

323 |

Kura-Araxes houses.These benches, however, were constructed of wood and then clay plastered. Pottery vessels were placed along the bench and found in situ around the fixed hearth, which was circular (150 cm in diameter). One large, upside-down jar stood in the hearth, with four smaller vessels and four pebbles placed beside it.53 As we have seen, this practice of upending a vessel on a hearth was not uncommon in the Kura-Araxes period. The hearth in Building 8 was sunk slightly into the floor and built in situ. Its projections – stylised anthropomorphic figures sitting with legs ‘embracing’ a central fire – recall the horseshoe-shaped stands characteristic of the Kura-Araxes culture.

A new trait that appears at the end of Period III at Berikldeebi is the platform, which Dzhavakishvili interpreted as a focal point for worship. While traces of twenty-one such platforms were discovered, only three examples were sufficiently well preserved to provide a reasonable understanding of their character. Unlike the buildings, mostly built in one general area, these platforms were scattered all around the site. Moreover, although each platform had signs of reuse, reflected by renewed layers of clay plaster, they may not have functioned simultaneously. What is clear is that the platforms were renewed. The intriguing question is this:Why did the platforms appear towards the end of Period III and why did they replace the hearth as focal point?54

In construction, the platforms were fairly standard. Platform 18, for instance, measured 1.5 m (length) x 1 m (width) x 0.35 m (height), and was positioned on a beaten clay floor. It was made of pebbles and clay mortar, as well as fragments of Bedeni pottery, and covered with slabs of clay baked hard. Features included horn-like projections and an ash pit. Scattered around the platform were a horseshoe-shaped hearth and pottery vessels, with one containing carbonised wheat.

Berikldeebi Pits

There is no clear distribution pattern for the numerous pits of Period III. Some are located beneath the floors of buildings, others were dug in the open, and yet others cut buildings and features. They were also dug very close to one another, or even cut into earlier pits, and are mostly of the same type (bell-shaped), differing only in diameter size (between 40 and 300 cm). Several well-preserved pits, complete with filling, suggest they were sealed with a thin clay layer, on the top of which was placed a small stone-pile, suggesting intentionality. Generally speaking, the pits were full of ashen earth, which mostly contained a limited assortment of material: fragments of ceramics, clay stands, broken cattle bones, pebbles, obsidian tools and their debitage, and, occasionally, fragments of building daub; millstones, pestles, zoomorphic clay figures, and axe moulds occurred sporadically. While this material may look as if it

53This practice of placing a pottery container upside down over the ash pit in the middle of the fixed hearth is found elsewhere, including at Sos Höyük and at Chobareti.

54Sagona 1998.