- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

344 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

(cattle and horse) supplemented by hunting (deer and onager) formed the basis of the economy.

Didi Gora and Tqisbolo Gora, in the Alazani Valley, provided a very useful sequence of deposits, comprising seventeen layers, assigned to the period 2500–1500 BC.111 The lack of tangible architecture, other than a few postholes that occasionally formed the coherent plan of a dwelling, led the excavators to suggest that the community had a mobile existence.This idea was reinforced by an absence of grinding stones, which one would expect to find in a sedentary farming community. No hearths or fireplaces were discovered, even though the sequence was interleaved with much burnt debris.At Tqisbolo Gora, four layers (Levels 5–8) were attributable to the Middle Bronze Age, with Level 6 yielding a calibrated date of 1880–1750 BC at 68.4 per cent probability.112

Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

Collectively, the Middle Bronze Age II is well known for the dazzling array of objects in precious metals and bronze, a good number of which are unique. In terms of technical execution and iconography, these objects reveal a fusion of local traits with foreign influences that reflect the southern Caucasus’ growing participation in a far-flung system of exchange extending to the shores of the eastern Mediterranean during the second millennium BC.

Silver Goblets: The Narratives

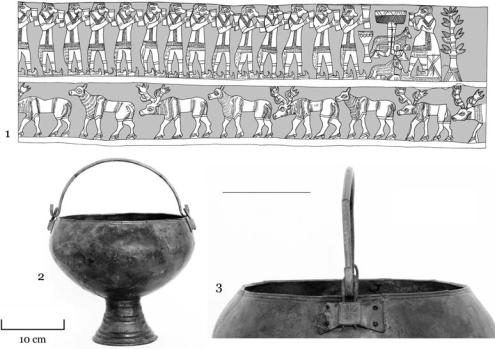

Two marvellous embossed silver goblets found in the wealthy kurgans at Trialeti and Karashamb stand out, and must both belong to the same artistic tradition. One comes from Trialeti Kurgan 5, excavated in the 1930s by Kuftin.113 It is divided into two friezes that depict a procession of figures bearing offerings approaching a seated figure, with a row of woodland animals in the lower register (Figure 7.19(1)). The top register portrays the seated individual and the twenty-two standing figures facing him.All are depicted in the same manner – with beards, prominent noses, and large eyes. Each is holding a narrow goblet and wearing shoes with upturned toes.Their costume is identical too – a fringed tunic decorated along the edges with an attached animal’s tail (fox or wolf?) hanging from the back. Between the seated figure and the first person in the procession is the focal point of the scene: two recumbent animals, a tall item with narrow base that is likely to represent a frame drum,114

111Korfmann et al. 1999, 2002; Mansfeld 1996.

112Kastl 2008: 188.

113Kuftin 1941: 87, fig. 93, pls 91–2; Gogadze 1972: 77, pls 17–18; Zhorzhikashvili and Gogadze 1974: 71 no. 486, pls 56–7; Miron and Orthmann 1995: 32, 86–7, 238; Rubinson 1999; Soltes 1999: 146; Boehmer and Kossack 2000.

114A frame drum has a drumhead with a width greater than its base. Given that similar shapes are found amongst the pottery repertoire, the shell of the drum is likely to have been made of terracotta and its drumhead was presumably made of rawhide.

The Middle Bronze Age II (2000/1900–1700 BC) |

345 |

Figure 7.19. (1) Trialeti silver goblet, imagery rolled out (after Boehmer and Kossack 2000); (2–3) bronze footed cauldron and detail of handle (photographs A. Sagona).

and a table with hooved feet. A tree stands behind the seated figure and acts as a divider in the scene.The lower frieze has a procession of deer, male and female in alternate positions, walking to the left. Kuftin emphasised the local fl avour of the narrative, whereas others have compared the imagery to Hittite art, or taken one step further and associated it with Indo-European mythology.115 Rubinson has made the sensible suggestion that the Trialeti artisans, like those from Hatti, drew inspiration from the art of the Old Assyrian period. She points out that specific iconographic features such furniture with hooved feet and shoes with upturned toes are found on the glyptics from Kültepe (Kanesh) and contemporary sites.

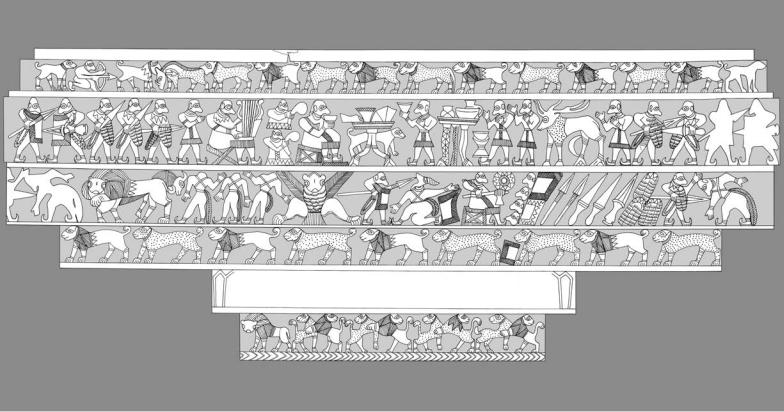

The counterpart goblet was found in the cemetery at Karashamb, in Armenia, in the late 1980s.116 Its imagery is more complex and portrayed in five registers – four across the body and one on the foot separated from the others by a geometric pattern (Figure 7.20). Three of the friezes depict primarily animals, which, in contrast to the Trialeti goblet, are mostly lions and leopards. The narrative in the top frieze begins with an archer and his dog;

115Kuftin 1941: 90. For Hittite art, see Miron and Orthmann 1995: 238, and for IndoEuropean mythology, see Areshian 1985.

116Oganesian 1992a; Boehmer and Kossack 2000; Rubinson 2003.

346

Figure 7.20. Karashamb silver goblet, imagery rolled out (after Boehmer and Kossack 2000).

The Middle Bronze Age II (2000/1900–1700 BC) |

347 |

nearby, a wild boar, wounded by an arrow, is shown having his neck bitten by a lion. Like the Trialeti goblet, however, the two animal friezes on the body of the Karashamb goblet conform to similar iconographic principles – moving left in a procession and an alternating fashion.

Rampant animals in a heraldic pose with their heads turned backwards, except for one lion in profile looking front-on, are depicted in the lowest frieze.The widest bands show a multiplicity of activities involving conflict and ritual.Whereas the human figures have similar facial features to those on the Trialeti goblet, their heads are shaven.The focal point is the seated figure in the second register. He is larger than the others, seated on a (woven?) stool with podium, holding a cup by its narrow base.Although his head is mostly shaven, he appears to sport a ponytail. He wears a short-skirted fringed tunic and shoes with upturned toes, a similar costume to other men in this ritual scene; an armband (or short sleeves?) completes his attire. In front of him is a table with hooved feet, bearing various objects, one of which appears to be a conical cup. On the other side of the table, facing the seated figure is a standing man with raised hands, also holding a cup, and behind the table is an animal, possibly a dog. Next is a tripod table, a biconical stand holding a bowl, followed by two males, a deer and another man. Returning to the principal figure, behind him are two kneeling/squatting figures holding what appear to be fans, or possibly instruments. The next figure, moving left, is a musician playing a lyre; he is seated on a cross-legged stool and wears a zigzag-edged collar.This ritual scene ends with another standing figure, again with upraised arms. Men armed with weapons and holding U-shaped or square shields, possibly woven, fl ank this core scene on either side. There are two juxtaposed pairs brandishing spears and daggers, engaged in battle, and three armed warriors are heading towards the principal seated figure. Each of these soldiers also has a scabbard.117

The third frieze appears to be more compartmentalised in its activities and each section deals with conflict.The focal point is the hybrid creature (a lionheaded bird) situated beneath the principal figure in frieze two. To the left of the creature are three headless bodies that have a (fox?) ‘tail’ hanging from their waist similar to those worn by figures on the Trialeti goblet.To the left are a lion and goat, standing beside each other, with the lion looking front-on. Each of the vanquished warriors in this register is dressed in a similar fashion – cross-straps across their chests, shoes with turned up toes, and a tail.The victors, on the other hand, are armed and hold shields.To the right of the hybrid creature are four interconnected scenes: an armed warrior pointing a spear at the head of his enemy, who has succumbed; a seated figure wielding an axe and facing four heads protruding from two rectangular shields; weaponry – spears, daggers, and shields; and another battle scene.

117I agree with Rubinson (2003: 135) on this point, as opposed to Boehmer in Boehmer and Kossack 2000: 21, who considers them ‘tails’.