- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (2500–2000 BC) |

325 |

originally with pitched roofs, were uncovered and each had been destroyed by fire. Buildings 1–3 have two hearths each, one of stone and the other of clay. A circular clay floor, situated in the open, likewise has evidence of burning. But the most conspicuous feature was a rectangular terracotta pan supported on stones positioned in a corner of the settlement, which appears to have been an outdoor cooking area. Like the other sites, Badaani has pits – ten of them, with an interleaving of ash and debris, individually sealed with a small heap of stones. Small miniature clay vessels found only in the pits strengthen the idea of intentionality.

The renewed investigations at Natsargora in the Khashuri district have also helped in clarifying the relationship between the late Kura-Araxes and the Bedeni periods.60 Although the architectural evidence is fragmentary, clarification of the stratigraphy and the sequence of pottery are telling. It appears that the Kura-Araxes settlement was badly disturbed by the later Bedeni pits, which caused the mixing of material. Pits dug during the Late Bronze Age caused additional disturbance. With the delineation of pits, the conclusion drawn from the early excavations – namely that Kura-Araxes and Bedeni material co-existed – has been replaced with a view that occupation at Natsargora followed the sequence Kura-Araxes, Martkopi, and Bedeni. The co-existence of Kura-Araxes and Bedeni features, according to Makharadze, can also be seen at a number of other sites, including Ilto (in Kakheti), complexes II and III at the Beshtasheni fortress, Barrow 12 at Trialeti, and Barrows N5 and N9 at Shulaveri.61 He also maintains that the Bedeni interlude comprised two developmental stages: the first saw the association of both fine ceramics and roughly made vessels in settlements, while in the second phase, when Kura-Araxes elements disappeared, fine Bedeni pottery was restricted to barrow burials and roughly fashioned containers manufactured for use in settlements.

Crafts and Technology

Ceramics

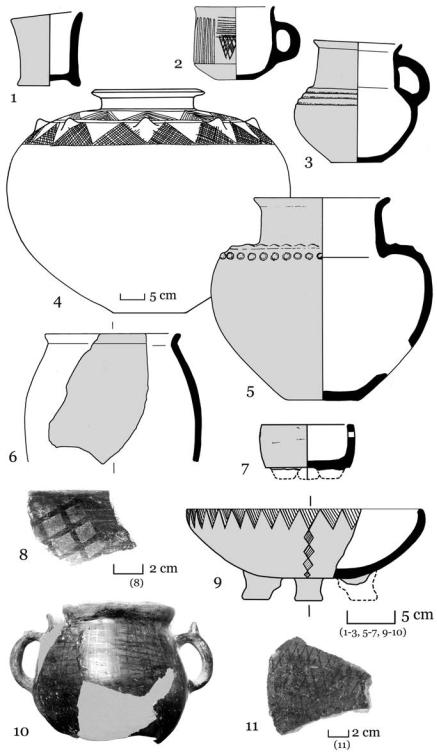

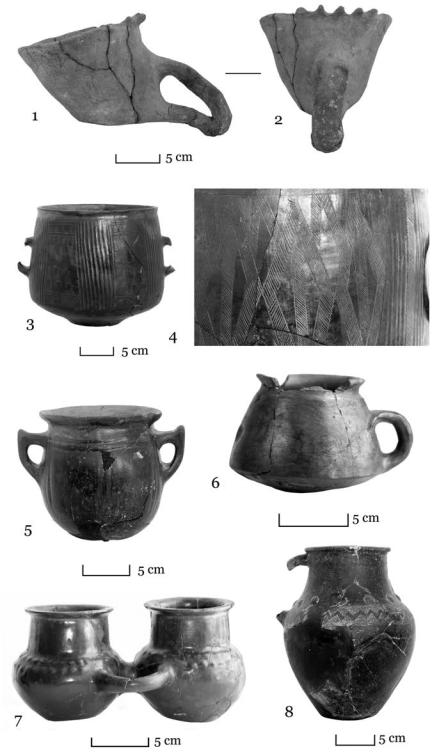

There are two types of Bedeni pottery – fine wares and coarse wares. Burial pottery generally has a fine, compact paste and is very well manufactured. Containers are thin-walled and highly burnished to an almost mirror finish. Their surfaces often bear traces of a silvery coating that can rub off if not handled carefully.This appears to be graphite or haematite that was crushed to a powder and applied to the surface prior to burnishing,when the clay was leather hard. Cups and pitchers were popular and come in a variety of forms, such as a cylindrical and two-handled cup, a one-handled pitcher with a rounded belly

60Rova et al. 2010; 2014; Puturidze and Rova 2012a.

61Makharadze et al. 2016: 16.

326 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

and straight neck, and those with a low set conical girth (Figures 7.12–7.13). Containers are often decorated with an empanelled, finely incised geometric design.A pear-shaped vessel with a tall, cylindrical neck is decorated with fl at, horizontal fluting at the shoulder. Quite novel is the tripod bowl, occasionally with bent legs and a perforated horizontal lug (Figures 7.10(3) and 7.12(7, 9)). Although known in the south Caucasus, the home of this type is the northern Caucasus, as their numbers at Bamut indicate.The sense of decorativeness appealed to Bedeni potters. Relief knobs, fluting, and fine incisions were executed with precision, often empanelled, and rarely mixed. Some vessels had discrete ornamentation, whereas others had all over patterns (Figure 7.13(3–4)). Overall, the impression one gets is of a highly developed potting tradition that was over time inspired by new advances in metalworking, for many of the vessels have a metallic look about them.

Bedeni coarse wares, on the other hand, shared technological and other attributes with Kura-Araxes. Found mostly in settlements, the coarse wares have thicker walls than their fine counterparts, but not as thick as Kura-Araxes. Because the firing does not display the controlled atmosphere required to produce the fine wares, vessels are often mottled red-brown and black in colour. Forms are limited and not as adventurous as the angular fine containers (Figures 7.12(6) and 7.13(1–2)).

Woodworking

Attention should also be drawn to the high level of woodworking, exquisitely represented by the tripod tray carved from a single piece of wood (Figure 7.9(1)). Its figured, bent legs are mortised into holes, and a perforated lug handle attached to the rim enabled it to be hung on a wall so that the grooved circular ornamentation on the underside could be admired. Taken together with the skilfully crafted and assembled wooden wagons and tools such as grooved chisels and fl at axes placed in the barrows, we can infer that skill in woodworking and carpentry was much valued.

Flaked stone

Stone items also display a level of sophistication. In Figure 7.9(4) we see typical Bedeni projectile points. Their sides are convex and exhibit careful pressure fl aking on both surfaces, squamous in appearance, and along the blade edge. Thin in cross-section, the broadest area is near the midsection or towards the base. A Bedeni point is characterised by a distinctly hollowed base, which is steeply fl aked to dull the edges for hafting on wood or bone.This new projectile design, different to the tanged and barbed arrowheads of the Kura-Araxes, is seen as a more effective weapon with greater penetrating power.62 Bone and antler points are also typical (Figure 7.9(5)).

62 Smith 2015: 142–4.

Figure 7.12. Bedeni pottery: (1, 6, 8, 11) Sos Höyük (after Sagona 2000); (2–3, 5) Bedeni Barrow 5 (after Gobejishvili 1980); (4) Shengavit (after Sardarian 1967); (10) Berikldeebi (adapted by C. Sagona, photographs A. Sagona).

327

328 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

Figure 7.13. Bedeni pottery: (1–5) Berikldeebi; (6–8) Bedeni (photographs A. Sagona).