- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (2500–2000 BC) |

309 |

led to the rather exaggerated examples of the later Bronze Age. At Sachkhere the axes have a tubular shaft for the handle and a sweeping blade broadening towards the end (Figure 7.4(1, 3)). Flat axes, spearheads with a prominent midrib, and square-sectioned bayonet-like weapons are also part of the assemblage (Figure 7.4(11)).

Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

What caused the demise of the Kura-Araxes complex and the rise of the barrow cultures is a moot point. ‘Cattle herding pastoralists’, according to Kohl,‘who habitually utilized ponderous oxen-driven wagons, [and] gradually moved south from the western Eurasian steppes into Transcaucasia’, provide the answer.29 As appealing as this crisp image is, we need to tread carefully.We do not have nearly enough secure radiocarbon dates from either side of the Caucasus range to substantiate this claim, nor, as we see, can we confidently say where wooden-wheeled vehicles were invented.Although the appearance of the Bronze Age barrow cultures is abrupt, a transitional period is evident in a number of places. Stepanakert Barrow 119 is one burial that reflects hybridity of this kind.30 As we have seen, the majority of Kura-Araxes burials were individual, with some tombs, especially the stone built structures, showing multiple interments.31 The Stepanakert barrow was a collective tomb with a material assemblage that draws on both the Kura-Araxes and Martkopi traditions.The coexistence of late Kura-Araxes and ‘Martkopi’ elements have also been reported from Badaani and Tsikhiagora, discussed below.

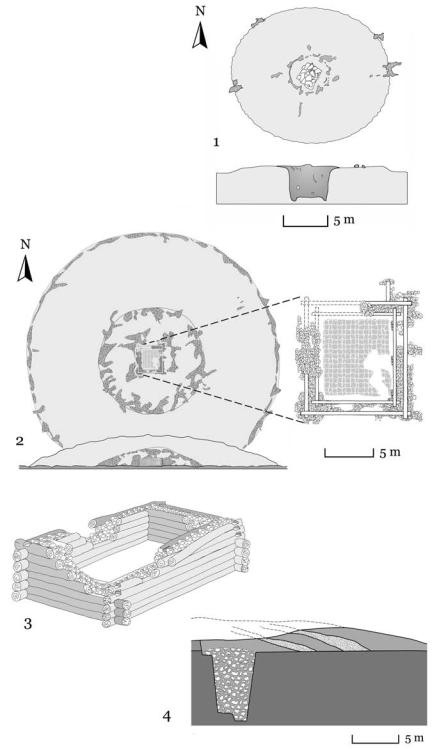

Communities of the Middle Bronze Age I buried their dead beneath large stone mounds that were sometimes covered with a layer of earth.This layering may have held some meaning, given that a few mounds appear to have interleaved layers of soil and stone, usually a combination of pebbles and field rocks.The size of the mounds varied greatly, from as high as 13 m for Martkopi Barrow 4 to Magharo that is barely a rise (50 cm) on the horizon, and their dimensions most likely reflected social status. Most barrows are circular in plan, though a few are more elongated. Six barrows were excavated at Martkopi.32 Barrow 4 is a good example of a well-preserved burial, replete with grave goods. It had an aboveground wooden mortuary chamber with walls two logs thick, supporting a wooden roof that was concealed beneath a mound 100 m in diameter and 13 m high (Figure 7.5(2)).33 The chamber was substantial, measuring 11 x 10 m along the exterior and enclosing an interior space of 8 x 6 m. It was also well built and sturdy, displaying skills in carpentry that were

29Kohl 2007: 121.

30Smith 2015: 133.

31Poulmarc’h 2014a.

32Dzhaparidze 1998.

33Dzhaparidze et al. 1980.

310 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

Figure 7.5. Barrow plans: (1) Martkopi Barrow 6; (2) Martkopi Barrow 4;(3) wooden mortuary chamber of the Magharo barrow; (4) cross-section of Trialeti Barrow 10 (nos. 1–3 after Dzhaparidze 1998; no. 4 after Gogadze 1972).

Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (2500–2000 BC) |

311 |

one of the distinguishing features of this period. Its walls rose 2 m above the ground and were interlocked; for added strength, the space between the two log walls was filled with stones. Comparable structures were found at Magharo (Figure 7.4(3)), and at Zeiani in the Samgori Valley, near Sagaredzho.34 Rarely, tombs were furnished with steps, such as at Magharo.35

Other barrows sealed deep shaft tombs or structures buried below ground level, such as Martkopi Barrow 6 (Figure 7.5(1)). Beneath the floor of Zeiani Barrow 2, excavators reported a pit with a ceramic container half filled with human ashes. The early barrows at Trialeti are comparable: spacious shaft tombs – up to 4 m in diameter and dug up to a depth of 7 m – were backfilled with stones and then covered with a tumulus of earth and stones (Figure 7.5(4)). Trialeti Barrow 46, however, was different. It had a funerary log cabin containing the remains of a child, sealed under a tumulus 50 m in diameter.36

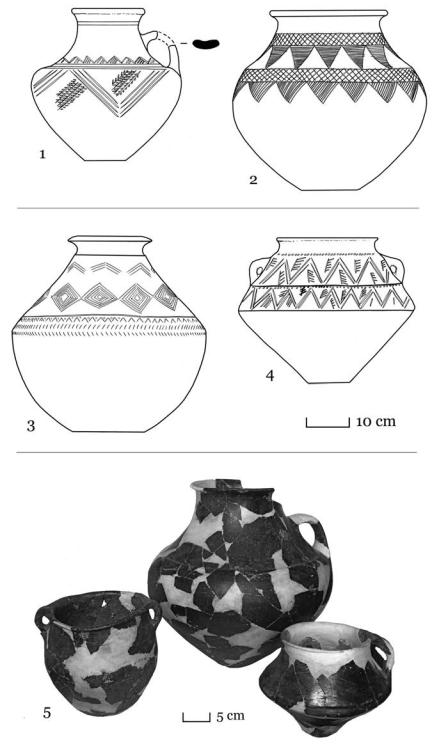

The most common item in the funerary assemblages is pottery.Vessels have a black polished exterior surface – never quite reaching the Bedeni lustre – and a smoothed pink interior, showing connections with the late Kura-Araxes and early Trialeti pottery. Martkopi forms also appear to develop out of these two horizons. There are large jars, and cups often have a single, broad, strap handle linking the rim to shoulder. In general, many of the vessels show a tripartite profile analogous to the shape of a pear – a long concave neck, a bulging girth, and a sharply tapering lower body, which ends in a narrow base that is often concave (Figure 7.6).The belly gradually became more angular, to the point where some vessels have a biconical appearance. Ornamentation is also a feature and comprises geometric incised designs, such as bands of nested zigzags, across the accentuated belly.The top of the shoulder is usually defined by a row of hatched triangles; the lower body is never decorated.

In Barrow 4 at Martkopi, grave goods surrounded the remains of three individuals who were laid on a fl agstone-paved floor.Along the edge of the tomb stood black burnished pottery containers surrounding an assortment of items placed in the centre of the chamber: four axes with an obliquely cut shaft-hole and diagonal blade; three fl at bronze axes that widen towards the blade, comparatively rare in this period but becoming more popular about a millennium later; a chisel, typically with a square head, cylindrical shank, and concave edge; and four fl at leaf-shaped ‘blades’ – it is difficult to determine whether these are lance or dagger blades, or whether they served the same purpose as the later, more rounded, and enigmatic Bedeni ‘standards’. At the eastern end, a huge amount of mother-of-pearl plaques were found, along with perforated boars’ teeth used as pendants, and carnelian and faience beads of various shapes.The deceased were adorned with gold and silver necklaces of bobbin-shaped beads,

34Dzhaparidze 1983.

35Bertram’s (2003: 45–55) ‘Stufengraber’.

36Kuftin 1941: 101; Zhorzhikashvili and Gogadze 1974: 10.

Figure 7.6. Early Trialeti and Martkopi pottery: (1) Dali Gora (after Dzhaparidze 1998); (2) Sos Höyük (after Sagona 2000); (3) Sos Höyük (after Sagona 2000); (4) Martkopi Barrow 2 (after Dzhaparidze 1998); (5) early Trialeti ceramics (photographs A. Sagona).

312