- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

Early Bronze Age IV/Middle Bronze Age I (2500–2000 BC) |

305 |

Whereas Bertram’s study focuses on the historical development of grave types, showing the remarkable diversity over this millennium and a half, other scholars have emphasised the assemblages, using them to develop elaborate chronologies, albeit in the absence of reliable radiocarbon dates.18

The following regional overview combines both approaches and examines the main archaeological traditions. It begins with the late Early Bronze Age (the second half of the third millennium BC) and then discusses the Middle Bronze Age developments of the second millennium BC. Geographically, it moves from the better known facies of the southern Caucasus to the north Caucasian foothills.

THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE

AGE I (2500–2000BC)

New results on the environment of the plateaus of the southern Caucasus during the third millennium BC show that, contrary to our earlier understanding, the region had a forest cover promoted by good precipitation and warm temperatures (Chapter 1).19 The degree to which environmental factors influenced change or choice is difficult to say. What is clear is the dramatic shift in human behaviour and material culture that appears to stem from eastern Georgia.The early Barrow period is sometimes referred to as Early Kurgan I and Early Kurgan II on the basis of grave goods, especially changes in pottery and metalwork, though radiocarbon readings now suggest the two stages overlap.20 In any case, a slightly earlier group includes a few barrows at Trialeti, on the Tsalka Plateau, and others at Martkopi, in Kvemo Kartli, and Samgori. In Armenia, where the pulse is not so strong but is nonetheless evident, Martkopi is represented in the northern region, at sites like Berkaber, and also in the tombs at Shengavit in the Ararat plain.21 At present the western outlier is Sos Höyük, near Erzurum.22

The second, better-represented, and slightly later group comprises the Bedeni barrows in the Alazani Valley and Shida Kartli. Bedeni is also represented in Armenia at several sites, in western Azerbaijan (Mingechaur) and in Dagestan (Velikent).23 Again Sos Höyük appears to be on the western border, yielding just a few Bedeni imports.To these barrows should be added the few

18Since Kuftin’s (1941) report on the Trialeti barrows, there have been many studies on the chronology of the Trialeti culture, including Schaeffer 1943; Piggott 1969; Gogadze 1972; Rubinson 1977; Dzhaparidze 1994.

19Connor and Kvavadze 2014; Kvavadze et al. 2004: 267.

20Dzhaparidze 1983, 1993, 1998; Edens 1995; Bertram 2010.

21Smith et al. 2009: 52–5.

22Sagona 2000.

23Dedabrishvili 1979; Gobedzhishvili 1980; Smith et al. 2009: 52; Gadzhiev et al. 1997; Smith et al. 2009: 52.

306 |

The Emergence of Elites and a New Social Order |

settlements and sanctuaries we have for the Bedeni period, such as Berikldeebi and Zhinvali. According to Zurab Makharadze, the Bedeni tradition is totally foreign to the southern Caucasus and its arrival from the north facilitated the decline of the Kura-Araxes complex.24 The ‘invisibility’ of settlements may reflect research strategies that have targeted the conspicuous barrows; nonetheless, there is truth in the view that villages were more transient during this period.25

Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

Before we look at Martkopi proper, we need to highlight a transitional site that straddled the Early and Middle Bronze Ages. Sachkhere is located at the northern edge of the Imereti Province in Western Georgia and has yielded more metal objects than at any other site of this period. These objects foreshadowed, in a striking way, the trend in access to resources and the emergence of inequality. Sachkhere comprises three locations: Nacherkezevi and Tsartsis Gora which are located in the township of Sachkhere, and Pasieti in the nearby village of Koreti.26 G. Takaishvili conducted the initial small-scale investigations at Sachkhere in 1910, which were followed by Kuftin’s intermittent excavations before and after World War II and Dzhaparidze’s 1955 expedition.27

Typically, the Sachkhere mounds were built of stone – large ones around the base and smaller stones sealing the top.The graves consisted of earthen pits in which the deceased was placed in a flexed position, usually on the right side. None of the skeletal material is well preserved. In addition to the copious quantities of metalwork, provisions included handmade ceramics with a black polished exterior and pink smoothed inner surface, decorated with incised and relief patterns.

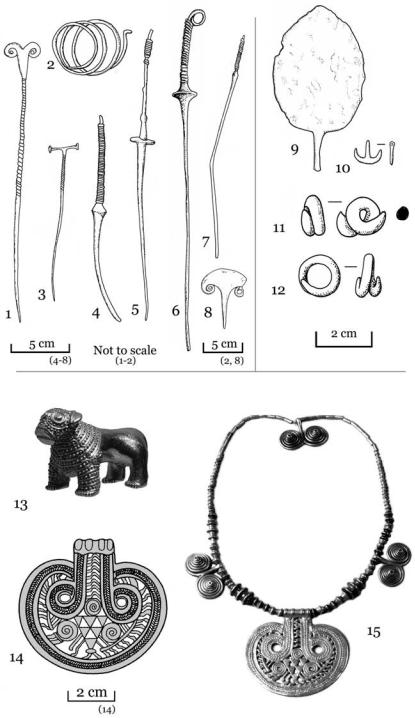

Amongst the bronze jewellery we have bronze lunate hair-rings, coiled bracelets, temporal rings, anchor pendants, and three types of pins: double spiral-headed,T-shaped, and loop-headed with a twisted upper shank, roughly in that chronological order, with latter two particularly well represented (Figure 7.3(1–6)).28

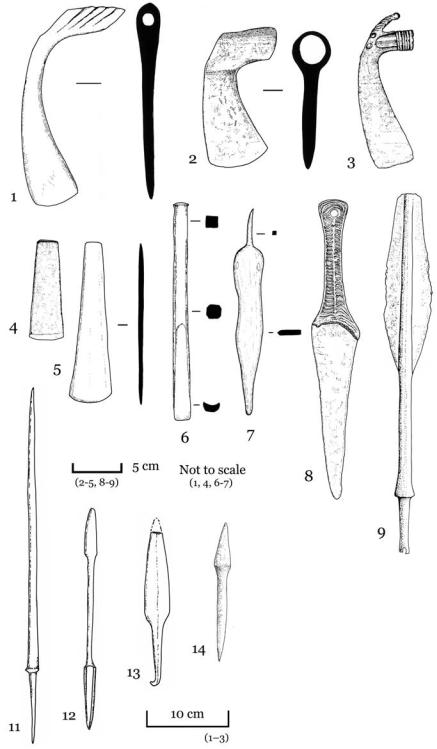

Notable weapons are the bronze daggers with cast handles decorated in relief and perforated at the end of the hilt found at Tsartsisgora and Koreti (Figure 7.4(8)). But it is the axe that began a significant transformation that

24Makharadze et al. 2016: 16.

25Sagona 2004.

26Dzhaparidze 1992.

27Takaishvili 1913. Kuftin opened ten barrows at Nacherkezevi in 1939 and sixteen more in 1951. Dzhaparizde renewed investigations there in 1955. Both also excavated at Tsartis Gora and Koreti (Kuftin in 1945–6, and Dzhaparidze in 1955). None of these sites is fully published.

28Gambashidze et al. 2010; Carminati 2014.

Figure 7.3. Late Early Bronze Age – Middle Bronze Age jewellery: (1, 7) Koreti; (2–6) Sachkhere, (8) Dzagina; (9) Martkopi Barrow 3; (10) Shida Kartli; (11) Silitschi Barrow 2; (12) Sos Höyük Burial (after Sagona 2004); (13) gold lion,Tsnori (courtesy Wikimedia Commons); (14) pendant from necklace, Ananauri (Kakheti) Barrow 2 (after Pitskhelauri 2006); (15) necklace Ananauri (Kakheti) Barrow 2 (after Abramishvili 2010).

307

Figure 7.4. Late Early Bronze Age – Middle Bronze Age weapons and tools: (1) Koreti; (2, 4) Martkopi Barrow 5; (3, 5) Sachkhere; (6) Bedeni Barrow 5; (7) Eliste; (8, 9, 11) Tsartis; (12) Kulbakebi; (13) Tbilisi; (14) Martkopi Barrow 4 (after Sagona 2004).

308