- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

116 |

Transition to Settled Life |

pendant from the neck and loose festoons. In this regard, they have closer affinities with the northern Ubaid than the Halaf. Similar wares have also been found at Tilktepe andYılantaş, near Van.97

The plain Neolithic ceramic wares from the south Caucasus, then, represent a local production that displays few affinities with Anatolia or Iran. Certain similarities could possibly be drawn with Umm Dabagiyah and other Hassuna assemblages in Mesopotamia, but these remain loose. A few of the painted items display the craftsmanship of Halaf wares, but on the whole they are local imitations of Halaf, or contemporary traditions of the northern Iranian Plateau.

Chipped and Ground Stone

Flaked stone tools display sameness in the overall assemblage,but site-specificity in terms of the proportion of types and raw material used.

As in Armenia, the Shulaveri-Shomutepe lithic assemblage is overwhelmingly obsidian. At Shulaveri, obsidian represents 82 per cent of the chipped stone industry in Level IX, increasing to 98 per cent in the latest deposit; the rest was chert. A variety of obsidian sources were exploited, but knappers in the Kvemo Kartli region procured their obsidian from the Paravani outcrop.98 Shomutepe, Toyre Tepe, Gargalar Tepe, and Baba Dervish, the Azerbaijani half of this group, also have a chipped stone industry worked from Paravani obsidian, though the inhabitants of the Kazakh district also exploited the Atis source in Armenia.99 Stone knappers from Ararat sites procured their nodules from many deposits, but mostly from the Arteni source in the western half of the Ararat Plain.100 The next most exploited source was the Gutansar deposit, which was either less desirable or perhaps less accessible in terms of social boundaries. Obsidian was procured from other deposits, each a considerable distance from both Aratashen and Aknashen-Khatunarkh, including Geghasar (in the south Gegham Mountains), Hatis, Kars, Van, and another unknown source. Chipped stone tools of the Mil-Mugan group, however, have a large component of flint, as does the repertoire from Alikemek Tepesi (78.3 per cent flint).101

Shulaveri-Shomutepe sites are characterised by abundance and diversity of fl ake tools, a large quantity of scrapers, the adoption of advanced blade techniques, and ground stone artefacts. At Shulaveri, there is a shift from a largely fl ake assemblage in Layer V to a predominately blade industry in the upper levels (Layers I–III). Blades are generally standardised – wide and long,

97Korfmann 1982; Marro 2007.

98Badalyan et al. 2004b.

99Arazova 1974: 8. Badalyan et al. 2004a, 2010.

100Badalyan et al. 2007: 43–8; Badalyan et al. 2010: 194–6. 101 Arazova 1974: 21.

Pottery Neolithic: The Central and Southern Caucasus |

117 |

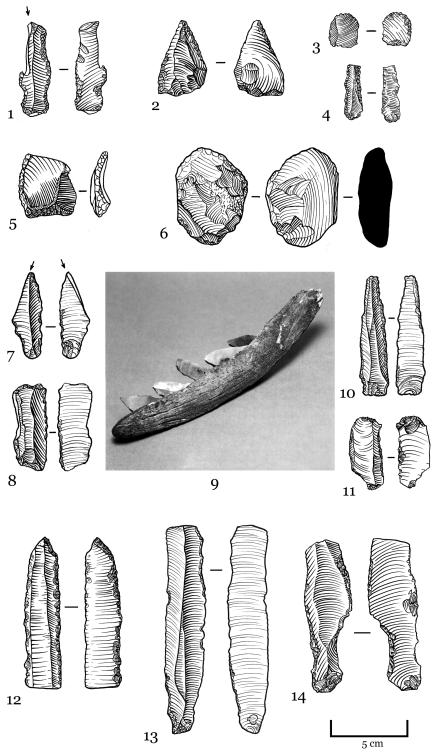

measuring up to 15 cm – and reduced from conical cores. Even so, the tool kit is fairly limited overall – chisels, scrapers, splintered pieces, drills, and denticulated blades (Figure 3.12). Conspicuously absent from the lithic assemblages are projectile points.

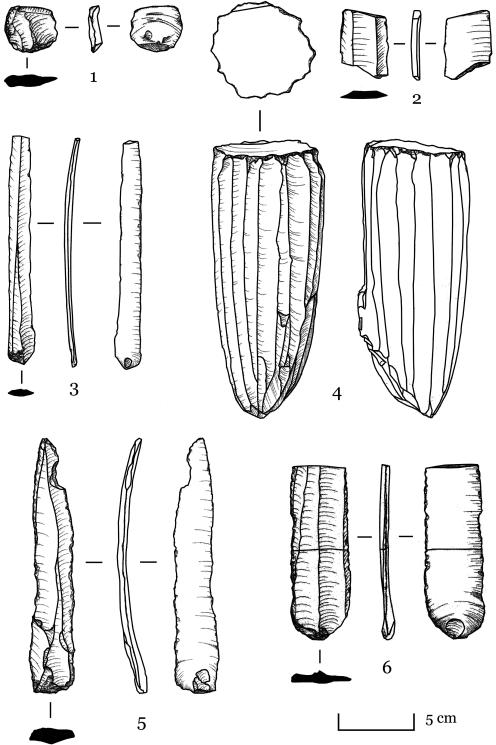

By contrast, the Aratashen and Aknashen-Khatunarkh industries, as well as those of the Shomutepe sites, are primarily blades (Figure 3.13). In addition to tools and debitage, many nuclei were found, including some elegant and unexpended pyramidal cores. Blades were often snapped into segments and inserted into sickle handles or into a threshing sledge (a tribulum), the different functionality apparent from the glossier use-wear sheen on sickle blades. Technologically, the tools were knapped, using pressure applied with a crutch or a lever and indirect percussion. Of these techniques, lever pressure, whereby a long lever, usually equipped with a point, produces lengthy blades, is noteworthy for its antiquity.102 Only stone tools from Franchthi Cave (Greek Early Neolithic) and Varna (Bulgarian Chalcolithic) are dated earlier, and there, lever pressure was used on flint, not obsidian. While contemporary lithic industries from sites of the Shulaveri-Shomutepe culture share morphological elements with the Aratashen assemblage, they do not appear to have used lever pressure.

Chipped stone tools of the Mil-Mugan group are not as diverse, nor as sophisticated as those from Kvemo Kartli and the Ararat Plain.

Most tools are expedient fl akes, with retouched implements very much in the minority. Both the scarceness of cores, indicating that nuclei were fully expended, and the coarseness of flint suggests the community of Kamiltepe might well have been excluded from stone resources.

Neolithic sites have also yielded many ground stone tools used for grinding, pounding, abrading, and chopping. Items include rubbers and saddle querns, mortars and fl at grinding slabs, wasted hammers and edge-ground axes, slingstones, and ‘polishing tools’, as well as bun-shaped grooved stones possibly used as spoke-shaves, and perforated stone weights (Figure 3.10(7–14)).103 Amongst the Kvemo Kartli sites, these macrolithics are fashioned from several stones such as sandstone, basalt, and granite. While food processing was their main function, traces of ochre on some slabs from Imiris Gora indicate that grinding colour and minerals was also a function in later periods. Similarly, the Khramis Didi Gora macrolithics point to craft production – sharpening wood and polishing bone – at the end of the Neolithic. Edge-ground axes, fairly ubiquitous in the south Caucasus, are quite rare in the Near East. Quite different in form from these macrolithics are the stone balls used as slingshots from

102Badalyan et al. 2007: 48. Lever-pressured blades are attested in the Tigris and Euphrates Valleys and the Anatolian Plateau from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B; see AltınbilekAlgül et al. 2012.

103Hamon 2008 (Kvemo Kartli); Badalyan et al. 2010: 197–8 (Aknashen-Khatunarkh).

Figure 3.12. Neolithic fl ake Stone tools from the southern Caucasus: (1–5, 6, 11, 14) Shulaveris Gora; (7, 8, 10, 13) Imiris Gora; (12) Khramis Didi Gora (after Kigurdaze 1986, Kiguradze and Menabde 2004, photograph courtesy the late T. Kiguradze).

118

Pottery Neolithic: The Central and Southern Caucasus |

119 |

Figure 3.13. Neolithic fl ake stone tools and prismatic core from Aratashen (after Badalyan et al. 2007).