- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

110 |

Transition to Settled Life |

all, and heads are stalk-like.Another statuette has three strips of clay laid across the front of the torso. A head is particularly well crafted with deep-set eyes and a white painted face.The legs of a stick figure, decorated with incisions, come from Shulaveri, whereas Gargalartepe has a female stalk figurine covered all over with small incisions possibly showing clothing or even body decoration.These are comparable to markings on the lower half of a similarly decorated seated figurine from Aruklo.86 Another incised cone-shaped figurine was found at Göytepe. Schematic human figurines are present in the upper levels at Imiris Gora and Shomutepe, though not plentiful.

Materiality and Social Relations

Ceramic Vessels

Pottery fragments are found at all south Caucasian sites, but at some sites their numbers are relatively small, suggesting that not all communities were readily convinced that baked clay containers had advantages, even though their neighbours in Mesopotamia and Anatolia had perfected the craft of making them.87 Only twenty-four sherds were found in the four occupation levels at Hacı Elamxamlı, and about three times that number (seventy-five pieces) in the nine building levels at Shulaveri Gora. Further south at Aratashen, the founding villagers were also ambivalent about ceramics, but by Level I the quantity of sherds indicates the community came around to the new technology.88 At Arukhlo, on the other hand, the team quantified 16,702 pottery sherds in three seasons alone, even though the majority were smaller than 10 cm.89 As mentioned earlier, the unwillingness to manufacture pottery containers might point to an interaction with late Mesolithic populations, for whom baked clay storage utensils might not have been a priority. Or vessels were simply manufactured from perishable materials such as leather, basketry, or wood – materials that were abundant and lightweight.

Two broad ceramic groups distinguish the Neolithic of the southern Caucasus: a coarse plain ware, which is the most common and found across all regions, and painted wares that are fewer in number, clustering in Nakhichevan and the Mil-Mugan areas. Both were handmade.

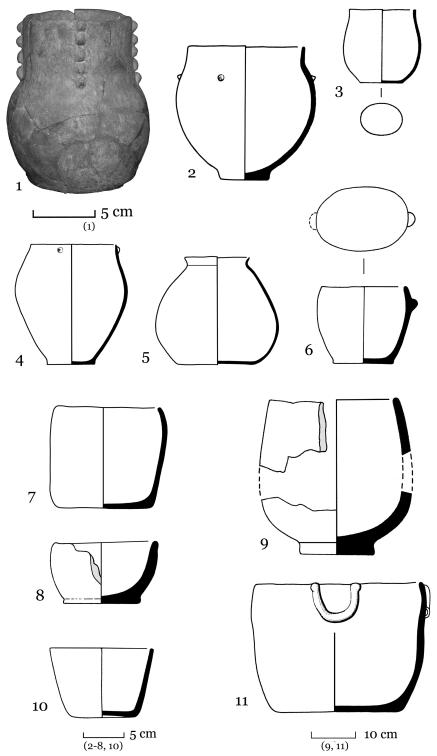

Plain ware vessels are simple in form and rough in manufacture (Figure 3.9).90 The Shulaveri-Shomutepe containers were constructed with coils, as were those from Aknashen-Khatunarkh, but at Aratashen slabs of clay were used;

86Neumann 2012, fig. 124.

87Nishiaki et al. 2015.

88Palumbi 2007a.

89Bastert-Lamprichs 2012.

90The Arukhlo preliminary reports provide a detailed analysis of ceramics; see, for example, Hansen et al. 2006: 14–22; Bastert-Lamprichs 2012.

Figure 3.9. Neolithic pottery from the southern Caucasus: (1, 9) Arukhlo; (2–5) Imiris Gora; (6, 7, 8, 11) Khramis Didi Gora, (10) Shulaveris Gora (after Kiguradze 1986, photograph A. Sagona).

111

112 Transition to Settled Life

finger impressions on both surfaces reveal how the slabs were melded together. Holemouth jars and wide-mouthed cooking vessels with an outward-turning rim are fairly common, with bowls and plates practically unknown; in later centuries some jars at Imiris Gora have a squat appearance. Lids are rare, as is the tall-necked, round-bodied jar from Kamiltepe. Containers are invariably fl at-bottomed and devoid of handles, apart from the occasional horizontal ridges, or solid lug handles set on the girth or at the rim for a better grip. Paste of these earliest containers is coarse and tempered with grit inclusions that occasionally break through the surface. Grog and obsidian were also used and added in liberal quantities by Armenian potters. At the end of the Neolithic, grit gave way to chaff, a shift demonstrated over most of the southern Caucasus. The exception to this is the steppe sites, including Kamiltepe, where chaff, chopped quite finely, was only rarely mixed with a scatter of grit inclusions.

The great variations in colour from black through red and browns to buff, as well as the mottled effect individual vessels bear, indicate little control in firing. Most likely, vessels were grouped together, covered with wood, chaff, or dung, and then set alight. Fire spots confirm the lack of control and low firing temperature, generally between 400° and 600° C. Cooking vessels are characteristically stained with soot and often irregular in form, but otherwise no different to other containers. Occasionally these wares are given a perfunctory smoothing and slipped on the exterior surface in grey-olive, or in the case of Kamiltepe, with a whitish wash. Shulaveri-Shomutepe potters constructed their vessels on a mat, which left its spiral or rectilinear impression on the base; this feature is absent at Aratashen, where vessels were constructed on a wooden or stone slab.

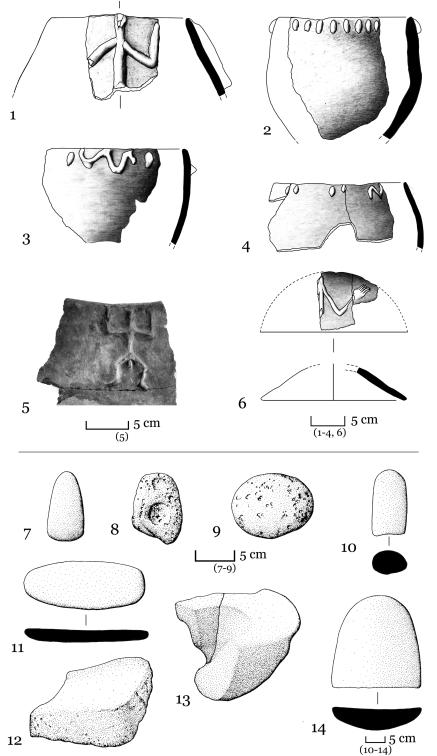

Ornamentation is regional. One-third of the diagnostic sherds at Arukhlo are ornamented, but most other sites recorded only a small quantity of decorated pottery (Figure 3.10(1–6)); at Aratashen, pottery is always plain. Plastic ornaments were the most common and begin early in the sequence: pellets of clay, circles, or ovoids, placed along the rim, or in short vertical rows down the body. Occasionally potters also applied other relief ornaments: U-shapes, isolated rings, short wavy lines, and a human stick figure. The latter are especially notable at Arukhlo, where a potter has finely articulated the hands (Figure 3.10(1, 6)). A few late vessels were incised: a large zigzag design along the shoulder comes from Gadachrili Gora, and vertical rows of fir-tree motifs were found on sherds from Shulaveri Gora.91 The fir tree is

91 Fir-tree ornaments are also attested at Odishi and Anaseuli II in western Georgia (Kiguradze 1976: 157), and at Ginchi, although these alone should not be taken as indicators of contemporaneity, especially in light of the re-thinking of the western Georgian Neolithic.

Figure 3.10. Neolithic pottery and ground stone tools from the southern Caucasus: (1–6) Arukhlo (1–4, 6, after Bastert-Lamprichs 2012 and courtesy Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, 5 photograph A. Sagona); (7–14) Imiris Gora (after Kiguradze 1986).

113

114 Transition to Settled Life

also a relatively common motif amongst Hassuna wares. Some of the rims are notched, foreshadowing the Chalcolithic Sioni wares.

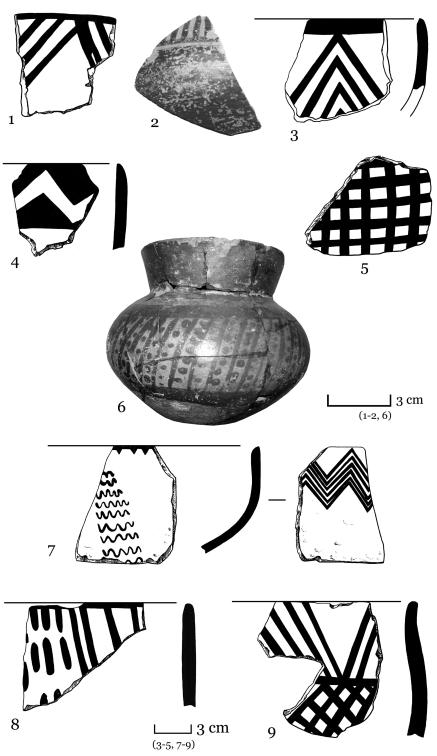

Despite the relatively small amount of painted pottery, it has received the greatest attention, because of its Near Eastern affinities (Figure 3.11).We have twenty painted sherds and a complete vessel with painted decoration from Kültepe I (Figure 3.11(6)), and a handful of painted sherds from Tekhut. At Alikemek Tepesi, painted pottery was found throughout the sequence (some 200 sherds), and in the uppermost levels (Horizons 0–1) it was found in association with Chalcolithic Sioni pottery distinguished by a comb- (or flint-) scraped exterior surface, which we shall discuss later.92 The central south Caucasian potters preferred not to decorate their wares with painted designs. Amongst the few painted examples we have are two finely painted sherds from Hacı Elamxamlı comparable to the Samarra and Early Halaf horizons.These two Mesopotamian imports, and two unstratified ones from Imiris Gora, are the northernmost outliers of traditions that are better represented in the Araxes Valley.

One group from Kültepe is chaff-tempered, but better in quality than the plain wares.They are slipped in cream and ornamented with simple geometric designs painted in brown, black, and, rarely, red, including nested triangles pendant from the rim and bands of diagonal or parallel lines.The other group, however, is well levigated with few impurities and is carefully fired, with a smoothed surface on which geometric designs were executed in black, brown, and red paint.93 A small jar with an everted rim from Kültepe I recalls Halaf ceramics.94 On the basis of quality and finish, Abibullaev correctly suggested that the first chaff-tempered group were most likely local imitations of imports, represented by the second, refined group.

Bowls, totally absent from the plain wares, are a popular form amongst the painted wares. Those from Alikemek Tepesi are quite large, with a diameter reaching 50 cm.Their designs are bold and geometric – nested zigzags,lozenges, net, and chequerboard – executed in black and red. Each of the patterns has a parallel amongst the Halaf ceramics of Mesopotamia, but especially amongst Dalma ware.95 The distinguishing trait of the Kamiltepe painted ceramics is the geometric designs executed in red or brown, occasionally in a fugitive manner, similar to repertoires in west central Iran.96 Although Kamiltepe is surrounded by painted pottery repertoires, its closest affinities are with sites in the Mugan steppes, and north Iran and the north-western Iranian Plateau. A haphazard execution defines Tekhut painted patterns, seen especially in the vertical-line

92Makhmudov and Narimanov 1972: 481; 1974b: 14.

93Abibullaev 1963: 163.

94Akkermans and Schwartz 2003: 133–9.

95Hamlin 1975: figs 4–7; Khosravi et al. 2013.

96D’Anna 2012: figs 48, 49, 53, 54, 55.

Figure 3.11. Neolithic painted wares from the southern Caucasus: (1) Mil steppes; (2, 6) Kültepe; (3–5, 7–9) Alikemek Tepe (after Munchaev 1994a, photographs courtesy V. Bakhshaliyev).

115