- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

Pottery Neolithic: The Central and Southern Caucasus |

103 |

into a variety of points and spatulae, most likely used for leather-working and basket-making.

The Ararat Plain

Although the early investigations atTekhut provided a glimpse of the Neolithic settlement of Armenia, the subject has been elucidated only in recent decades, through renewed investigations at Aratashen and its neighbour AknashenKhatunarkh, both located in the Ararat Plain.68 Detailed contextual data presented by Armenian-French teams show that while the Ararat Plain shares many cultural traits with both the Kvemo Kartli and Mil-Mugan regions, it developed its own distinctive character.Aratashen is now quite a small mound (ca. 60 m in diameter), once situated within the bend of the Kasakh River, which eroded its northern edge.The earliest settlers at the site (Level II) built a village densely packed with circular houses, comparable to those we have discussed in Kvemo Kartli (Figure 3.3(2)). Although chaff-tempered pisé was the basic medium of construction, recalling structures at Kültepe (Nakhichevan) and in northern Iran (Haji Firuz and Dalma Tepe), mud bricks were used in certain buildings.The dampness of the walls, however, did not allow excavators to determine the exact size of the dark bricks, whose edges melded with the lighter coloured mortar, prompting the idea that bricks and mortar might have been used for aesthetic reasons in the construction of houses, much as builders used them at Arukhlo.

Analyses of floor deposits enable some functions to be discerned. Several structures in Level IIb had beaten clay floors with notable amounts of manure and plant particles, suggesting that they may have housed animals. Despite the constricted size of the trenches, especially in Levels IIc and IId, the general impression is that the space between buildings was open. By Level IIa the settlement appears to have opened further, with more space between the structures. But whether this is a deliberate attempt to change the settlement plan or the result of erosion is difficult to determine. Round structures continued into Level I. Built from mud bricks, of a size that can now be determined (ca. 45 x 25 x 8 cm), these round houses were 5 m in diameter and linked together by walls.

Round structures made from pisé were also recorded at AknashenKhatunarkh from the lowest level (sub-Horizon V-5) onwards, and in some cases they had a rectangular extension.69 The round building in sub-Horizon V-4 was furnished with standard installations – oval pisé structures, a clay platform covered with a layer of pebbles and a hearth. Outside, a series of small oval

68Martirosian and Torosian 1967: 52–62; Torosian 1976 (Tekhut); Badalyan et al. 2004a, 2005, 2007, 2010 (Aratashen and Aknashen-Khatunarkh).

69Badalyan et al. 2010. R. M. Torosian excavated Aknashen-Khatunarkh in a series of intermittent campaigns between 1969 and 1982, but results have not been published.

104 |

Transition to Settled Life |

storage units once held cereals. Several saddle querns, rich botanical and animal remains, and pebble-built furnishings continue throughout the sequence, but the clearest architecture, in the form of two round pisé houses, was exposed in Horizon IV. A pair of buttresses that fl anked the entrance to the larger house recall a similar reinforcement used in Building 8 in Imiris Gora. The house had several floor surfaces of beaten earth strewn with many artefacts and furnished with several typical installations. Much the same pattern was found in Horizons II and III.

The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

Kültepe, located 8 km north of Nakhichevan, belongs to the Mil-Mugan group and it was the first site to reveal Neolithic settlement in the southern Caucasus.70 Regrettably we do not have a coherent plan, though we are told the settlement comprised both round and rectangular structures built of stone, usually with an earthen floor. Some of the round structures are quite substantial, with diameters greater than 7.5 m and walls to match, about 35– 55 cm thick. Rectangular buildings measured 4 x 3 m.71 Precise information on the Neolithic of Nakhichevan is now emerging from Shorsu, where rectangular rooms and ceramics can be dated to the second half of the sixth millennium BC.72

More informative is AlikemekTepesi in the Mugan steppes.Its 4 m sequence, numbered from 1 to 5 (top to bottom), revealed an important change in architecture apparent elsewhere in the Near East, namely a shift in plan from round structures to fully rectangular buildings.73 This transformation most likely represents a change in social organisation from a more communal-based village to one that is oriented towards the nuclear family.74 Throughout the entire occupation of the site, the inhabitants of Alikemek always built their homes from mud bricks,ranging in size from 50 x 20 x 12 cm to 35 x 18 x 9 cm.In the earliest levels, Horizons 5 and 4, houses were a variation on the Shulaveri-Shomutepe type. Here in the Mugan steppes, circular houses 3.5 m in diameter had small rectilinear annexes. This is similar to the situation in the Karabakh steppe, where Building 8 in Level 2 at Ilanly Tepe comprised a large circular house

70Abibullaev 1959a: 11–13, 1959b, 1963, 1965a, 1965b.

71Abibullaev 1965a: 157. Current collaborative Azerbaijani-French excavations at Kültepe will no doubt add much to our understanding of this site’s development.

72Bakhshaliyev 2015. To this can be added the chance Neolithic finds from Sadarak (Bakhshalyiev and Seyidov 2013: 1).

73The topmost level is designated ‘0’ and comprises mixed material from the Middle Bronze Age, disturbed by a Muslim cemetery. Reports on Alikemek Tepesi are mostly short notices; see, for example, Makhmudov and Narimanov 1972, 1974; Munchaev 1982: 118.

74Schachner 1999; Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 2008.

Pottery Neolithic: The Central and Southern Caucasus |

105 |

with a rectilinear extension.This house was furnished with a hearth and ten ceramic containers, whereas the rectilinear storeroom contained a number of tools – edge-ground axes, stone querns and rubbers, a bone hoe, and a range of obsidian chipped tools. As at Kültepe, this and other houses revealed traces of red painted floors.75

By Alikemek Horizon 3, we find a freestanding rectilinear building associated with a number of circular structures, some semi-subterranean, the next step in the transition from round to rectangular. Particularly noteworthy is Structure 22, measuring 3 m in diameter. Its lime-plastered interior walls had traces of a painted geometric design – circles, lines, dots, and U-shaped motifs – executed in fugitive red ochre.76 A large curved wall encircled some of the buildings. Fully rectangular structures were found in the youngest village at Ilanly Tepe, where they were associated with three oval-shaped hearths. A roughly similar plan to Alikemek has been found at Göytepe, where recent excavations down to virgin soil revealed a small rectangular building within a complex of connected round houses built with yellow or grey-brown mud bricks.77

Our understanding of the Mil Plain has been expanded markedly in recent years through exploratory investigations at several sites, including Kamiltepe (MPS 1) and its environs.78 Kamiltepe is situated on a high point overlooking the Kara Çay Valley. This vantage point would not only have provided visibility across the horizon, but it might also have had the practical purpose of protection against floods and the vagaries of a river that shifted its course during the sixth millennium BC. Although known for some decades from the surface material of painted pottery, Kamiltepe was excavated for the first time in 2009, as part of an Azerbaijani-German project. Excavations have revealed that a fully fledged Neolithic farming community (ca. 5600–5400 BC) occupied the site across two building phases, with strong ties to northern Iran and the south Caspian region.Yet, interaction with Shulaveri-Shomutepe group of sites appears to have been minimal. Communal co-operation is evident in a massive mud-brick platform, sub-circular in plan, attributed to the older phase (Figure 3.6). Evidence of a lightweight post construction was found on top of the wall, but the purpose of this structure remains unclear. Construction debris and a large quantity of bones of domesticated and wild animals were dumped around the structure, leading the excavators to suggest a social function for the platform, possibly involving the preparation of food and communal feasting.79

75Narimanov 1969: 396.

76Narimanov 1992: 52.

77Lyonnet and Guliyev 2010; Guliyev and Nishiaki 2012a, 2012b.

78Aliyev and Helwing 2009; Helwing and Aliyev 2012.

79Aliyev and Helwing 2009: 32–3; Ricci et al. 2012: 371; Helwing and Aliyev 2012: 8.

106 |

Transition to Settled Life |

Figure 3.6. Kamiltepe, the mudbrick platform (courtesy Deutsches Archäologisches Institut).

Ditches

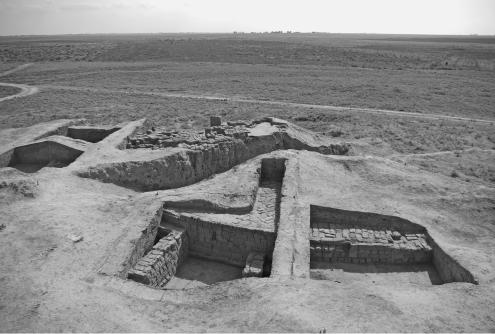

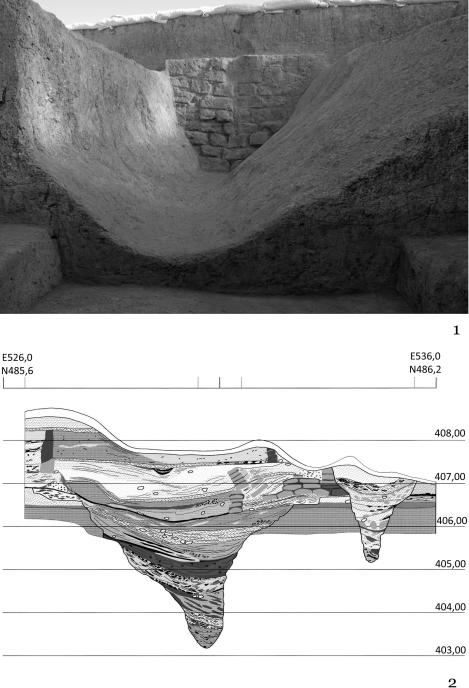

Another interesting, albeit enigmatic, feature at Kamiltepe is a system of four concentric ditches, with the outer ditch measuring about 50 m in diameter (Figure 3.7(1)).80 Although such a nested ditch system is so far unique in the southern Caucasus, individual ditches have been reported at Arukhlo (Figure 3.7(2)), Imiris Gora, Damtsvari Gora, and Kviriatskhali.81 These cuttings are either V-shaped or U-shaped in cross-section, and are assumed to be defensive structures, remnants of earth quarries or irrigation canals.The lack of a soil embankment or any evidence of a palisade rather undermines the notion of defence, and it is difficult to see how the ditches could be irrigation canals.

Drawing on the evidence from Neolithic Europe, where ditched enclosures (or roundels) and related features have been well studied as part of the prehistoric landscape, no single interpretative model can account for the diversity of plans and variations in chronology. In addition to fortification, the European ditched enclosures have been understood as cattle corrals and enclosed marketplaces.82 Other studies assume a more social model, arguing that they were

80Helwing and Aliyev 2012: 10–13.

81Helwing and Aliyev 2012: 13, and Chataigner 1995: 67, 69, for further references; see also Hansen and Mirtskhulava 2012: 67–9 for a clear cross-section and discussion.

82Petrasch 2015: 775–6.

Pottery Neolithic: The Central and Southern Caucasus |

107 |

Figure 3.7. Neolithic ditches from the southern Caucasus: (1) Kamiltepe;(2) Arukhlo (courtesy Deutsches Archäologisches Institut).