- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

The Great Divide: The Caucasus in the Middle Palaeolithic (150,000–35,000 BC) |

51 |

only a problem-oriented project and precisely excavated sites can offer. In relation to the southern Caucasus, but equally applicable to the northern regions, Daniel Adler and Nikolos Tushabramishvili explain the cultural areas sketched by Golovanova and Doronichev as ‘a) diachronic change; b) adaptation to specific environmental or topographical conditions; c) changes in climate and/or resource availability; d) the diffusion of people, ideas or technology; or e) poor sampling of the archaeological record’.33 To better understand which of these is the best fit, let us turn to some of the more precisely documented sequences.

Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

These two sequences serve as perfect entry points into a discussion of Middle Palaeolithic settlement and subsistence in the northern Caucasus. Matuzka Cave is a karst cavity and covers an area of approximately 900 m2.34 Its 4 m deposit has twelve stratified layers that are grouped into three horizons: Upper (strata 3a–c and 4a–d), dated to the Late Glacial (OIS 4–3), confirmed by the cold-environment plants and animals; Middle (strata 5, 5a, 5b, 6, and upper strata 7); and Lower (lower part of stratum 7, strata 8, and 8a) – Layer 7 is chronologically assigned to OIS 5e. Interestingly, cave bear (Ursus deningeri kudarensis) bones are the most common of the medium and large mammals.Yet, like the ungulate remains, they do not carry any signs of butchery, suggesting that the animals may have died of natural causes in the cave during hibernation.35 Although we are not clear on the purpose of the site, it seems to have had dual occupancy – hibernating cave bears in the winter and humans during the warmer months.This situation recalls Yarımburgaz Cave in Anatolia.36 Where the Matuzka went in the colder months is unclear.

Higher up the mountains (1,310 m asl) is nearby Mezmaiskaya Cave, discovered in 1987 and best known for its infant burial, from which scientists have recovered ancient DNA.37 Ultra-filtered collagen extracted from the infant produced a date of 39,000 ± 1,100 BP, which is in line with others from western Eurasia and suggests that the demise of Neanderthals was swift.38 It also argues against the hypothesis of Neanderthal survivals in the Caucasus, or a protracted period of 10,000 years of co-existence between them and anatomically modern humans.

33Adler and Tushabramishvili 2004: 96.

34Baryshnikov and Hoffecker 1994; Hoffecker and Cleghorn 2000; Golovanova and Doronichev 2003.

35Hoffecker and Cleghorn 2000.

36Sagona and Zimansky 2009: 13.

37Baryshnikov and Hoffecker 1994; Baryshnikov et al. 1996; Golovanova et al. 1999; Ovchinnikov et al. 2000; Golovanova and Doronichev 2003.

38Pinhasi et al. 2011.

52 |

Trailblazers |

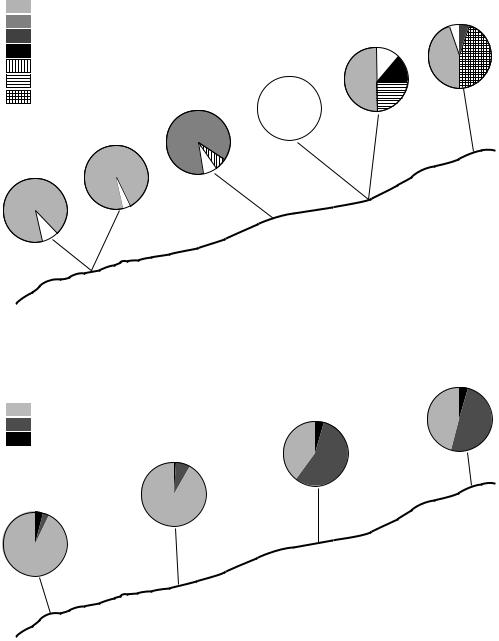

Mezmaiskaya Cave was created through erosion in Layer 4, one of twentythree geological strata, and was occupied soon after by humans, on and off for some 14,000 years (32,230–46,000 years BP).39 Their new home had a blocky limestone floor covered with many scattered stalactite fragments that had snapped off during the cave’s formation. It must not have been the easiest place in which to move around, and looking out from the entrance the occupants would have seen a grassy landscape mostly devoid of trees. Bones found within the cave show that mostly steppe bison, sheep and goat were hunted, though the family also had a taste for red deer; other faunal remains include cave bear, marmot, and wild ass. Most of the bones were well preserved with few signs of weathering, but displaying both cut marks and carnivore gnawing. Hunting patterns suggest the community preferred adult animals, though they did not discriminate in the case of sheep and goats.The lack of juvenile bison bones perhaps indicates these animals were targeted individually rather than as part of a herd.Animal taxa found at other Mousterian sites (Figure 2.6) emphasise the diversity. Broadly speaking, the chronometric sequence at Mezmaiskaya Cave tallies with that from Ortvale Klde, in the southern Caucasus (see following discussion).

Although the stone tool assemblages from Mousterian sites in the northern Caucasus can be small – only 166 artefacts were found at Matuzka Cave – they are nonetheless distinctive (Figure 2.5 (3–13)). In terms of their technology and typology, they belong to the East Micoquian, an industry including impressively crafted bifacial tools such as leaf-like projectile points for spears, small broad triangular hand axes, and side-scrapers or knives. In the later periods, bifacial tools are rare, and instead we see ventral and/or dorsal thinning. Most common are simple side-scrapers and convergent tools, found throughout the Middle Palaeolithic and accounting for more than a half of the toolkits. Side-scrapers come in a variety of types, including the so-called déjeté variety (a heavily reduced scraper also known as a skewed convergent scraper).

The Southern Caucasus

The southern Caucasus offers a different picture.With glaciated passes blocking human mobility northward, the isthmus has been aptly referred to as a cul-de-sac during the Middle Palaeolithic.40 That the region boasts such a large number of Palaeolithic sites is no doubt due in part to its geographic location – the end of the road – but equally to the favourable nature of its landscape. Even during the severe conditions of the Pleistocene, Georgia, in particular, had a natural setting and resources that would have attracted communities to the area. Sheltered from the strong impact of glaciation by the mountains,

39Within its 5 m-deep deposit of clay and pebbles, consisting of three Holocene and twenty Pleistocene strata, Layers 2, 2A, 2B1–4 and 3 belong to the Middle Palaeolithic. Above these were Upper Palaeolithic deposits (Layers 1A–C from top to bottom).

40Adler et al. 2006b: 165.

The Great Divide: The Caucasus in the Middle Palaeolithic (150,000–35,000 BC) |

53 |

|||

Bison |

|

|

Mezmaiskaya |

|

Cave Bear |

|

|

Barakaevskaya |

Cave |

|

|

|

||

Red Deer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cave |

|

|

Saiga |

|

Monasheskaya Cave |

|

|

Goat |

|

|

|

|

|

Gubs Shelter No. 1 |

|

|

|

Sheep |

Matuzka |

Sheep |

|

|

Goat & Sheep |

|

|

||

|

Cave |

Bison |

|

|

|

Goat |

|

|

|

|

|

Red Deer |

|

|

|

|

Giant Deer |

|

|

Il’skaya II |

|

|

1310 metres |

|

|

|

|

||

Il’skaya I |

|

|

|

Side- |

|

|

|

|

scrapers |

|

|

800-900 metres |

Bifaces |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Cores |

|

|

720 metres |

side-scrapers |

|

|

|

|

Isolated |

Denticulates |

|

|

|

Artifacts |

|

|

100 metres

Cores side-scrapers

Elevation

DZU Middle

Capra caucasica |

DZU Lower |

Bison priscus |

|

Other |

OK 4-UP |

|

|

OK 7-MP |

|

Elevation

Figure 2.6. Mousterian sites of the north-western Caucasus, showing their overall composition of mammal remains, their elevation above mean sea level, and principal stone artefact types (after Hoffecker and Cleghorn 2000, drawn by C. Jayasuriya).