- •Preface

- •Acknowledgements

- •Introduction

- •Russian Imperial Archaeology (pre-1917)

- •Soviet Archaeology (1917–1991)

- •Marxist-Leninist Ideology

- •Intellectual Climate under Stalin

- •Post–World War II

- •‘Swings and Roundabouts’

- •Archaeology in the Caucasus since PERESTROIKA (1991–present)

- •PROBLEMS IN THE STUDY OF CAUCASIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

- •1 The Land and Its Languages

- •GEOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES

- •Physical Geography

- •Mineral Resources

- •VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

- •GEOMORPHOLOGY

- •THE LANGUAGES OF THE CAUCASUS AND DNA

- •HOMININ ARRIVALS IN THE LOWER PALAEOLITHIC

- •Characteristics of the Earliest Settlers

- •Lake Sites, Caves, and Scatters

- •Technological Trends

- •Acheulean Hand Axe Technology

- •Diet

- •Matuzka Cave and Mezmaiskaya Cave – Mousterian Sites

- •The Southern Caucasus

- •Ortvale Klde

- •Djruchula Klde

- •Other sites

- •The Demise of the Neanderthals and the End of the Middle Palaeolithic

- •NOVEL TECHNOLOGY AND NEW ARRIVALS: THE UPPER PALAEOLITHIC (35,000–10,000 BC?)

- •ROCK ART AND RITUAL

- •CONCLUSION

- •INTRODUCTION

- •THE FIRST FARMERS

- •A PRE-POTTERY NEOLITHIC?

- •Western Georgia

- •POTTERY NEOLITHIC: THE CENTRAL AND SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Kura Corridor

- •The Ararat Plain

- •The Nakhichevan Region, Mil Plain, and the Mugan Steppes

- •Ditches

- •Burial and Human Body Representations

- •Materiality and Social Relations

- •Ceramic Vessels

- •Chipped and Ground Stone

- •Bone and Antler

- •Metals, Metallurgy and Other Crafts

- •THE CENTRAL AND NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •CONTACT AND EXCHANGE: OBSIDIAN

- •Patterns of Procurement

- •CONCLUSION

- •The Pre-Maikop Horizon (ca. 4500–3800 BC)

- •The Maikop Culture

- •Distribution and Main Characteristics

- •The Chronology of the Maikop Culture

- •Villages and Households

- •Barrows and Burials

- •The Inequality of Maikop Society

- •Death as a Performance and the Persistence of Memory

- •The Crafts

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •Ceramics and Metalwork

- •Houses and Settlements

- •The Treatment of the Dead

- •The Sioni Tradition (ca. 4800/4600–3200 BC)

- •Settlements and Subsistence

- •Sioni Cultural Tradition

- •Chipped Stone Tools and Other Technologies

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •BORDERS AND FRONTIERS

- •Georgia

- •Armenia

- •Azerbaijan

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Iran

- •Amuq Plain and the Levantine Coastal Region

- •Cyprus

- •Early Settlements: Houses, Hearths, and Pits

- •Later Settlements: Diversity in Plan and Construction

- •Freestanding Wattle-and-Daub Structures

- •Villages of Circular Structures

- •Stone and Mud-brick Rectangular Houses

- •Terraced Settlements

- •Semi-Subterranean Structures

- •Burial customs

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Structures

- •Hearths

- •Early Ceramics

- •Monochrome Ware

- •Enduring Chaff-Face Wares

- •Burnished Wares

- •LATE CERAMICS

- •The Northern (Shida Kartli) Tradition

- •The Central (Tsalka) Tradition

- •The Southern (Armenian) Tradition

- •MINING FOR METAL AND ORE

- •STONE AND BONE TOOLS AND METALWORK

- •Trace Element Analyses

- •SALT AND SALT MINING

- •THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

- •The Mobile and the Settled – The Economy of the Kura-Araxes

- •Animal Husbandry

- •Agricultural Practices

- •CONCLUSION

- •FUNERARY CUSTOMS AND BURIAL GOODS

- •MONUMENTALISM AND ITS MEANING IN THE WESTERN CAUCASUS

- •CHRONOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

- •THE NATURE OF THE EVIDENCE

- •THE SOUTHERN CAUCASUS

- •EARLY BRONZE AGE IV/MIDDLE BRONZE AGE I (2500–2000 BC)

- •Sachkhere: A Bridging Site

- •Martkopi and Early Trialeti Barrows

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Ananauri Barrow 3

- •Bedeni Barrows

- •Other Bedeni Barrows

- •Bedeni Settlements

- •Berikldeebi Village

- •Berikldeebi Pits

- •Other Bedeni Villages

- •Crafts and Technology

- •Ceramics

- •Woodworking

- •Flaked stone

- •Sacred Spaces

- •The Economic Subsistence

- •The Trialeti Complex (The Developed Stage)

- •Categorisation

- •Mound Types

- •Burial Customs and Tomb Architecture

- •Ritual Roads

- •Human Skeletal Material

- •The Zurtaketi Barrows

- •The Meskheti Barrows

- •The Atsquri Barrow

- •Ephemeral Settlements

- •Gold and Silver, Stone, and Clay

- •Silver Goblets: The Narratives

- •Silver Goblets: Interpretations

- •More Metal Containers

- •Gold Work

- •Tools and Weapons

- •Burial Ceramics

- •Settlement Ceramics

- •The Brili Cemetery

- •WAGONS AND CARTS

- •Origins and Distribution

- •The Caucasian Evidence

- •Late Bronze Age Vehicles

- •Burials and Animal Remains

- •THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE III (CA. 1700–1450 BC)

- •The Karmirberd (Tazakend) Horizon

- •Sevan-Uzerlik Horizon

- •The Kizyl Vank Horizon

- •Apsheron Peninsula

- •THE NORTHERN CAUCASUS

- •The North Caucasian Culture

- •Catacomb Tombs

- •Stone Cist Tombs

- •Wooden Graves

- •CONCLUSIONS

- •THE CAUCASUS FROM 1500 TO 800 BC

- •Fortresses

- •Settlements

- •Burial Customs

- •Metalwork

- •Ceramics

- •Sacred Spaces

- •Menhirs

- •SAMTAVRO AND SHIDA KARTLI

- •Burial Types

- •Settlements

- •THE TALISH TRADITION

- •CONCLUSION

- •KOBAN AND COLCHIAN: ONE OR TWO TRADITIONS?

- •KOBAN: ITS PERIODISATION AND CONNECTIONS

- •SETTLEMENTS

- •Symmetrical and Linear Structures

- •TOMB TYPES AND BURIAL GROUNDS

- •THE KOBAN BURIAL GROUND

- •COSTUMES AND RANK

- •WARRIOR SYMBOLS

- •TLI AND THE CENTRAL REGION

- •WHY METALS MATTERED

- •KOBAN METALWORK

- •Jewellery and Costume Accessories

- •METAL VESSELS

- •CERAMICS

- •CONCLUSION

- •10 A World Apart: The Colchian Culture

- •SETTLEMENTS, DITCHES, AND CANALS

- •Pichori

- •HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

- •CERAMIC PRODUCTION

- •Tin in the Caucasus?

- •The Rise of Iron

- •Copper-Smelting through Iron Production

- •CONCLUSION

- •11 The Grand Challenges for the Archaeology of the Caucasus

- •References

- •Index

Hoards and the Destruction of Wealth |

459 |

HOARDS AND THE DESTRUCTION OF WEALTH

‘Tales of treasure buried in remote locations, and guarded by possessive monsters’, as David Wengrow aptly notes, ‘are deeply embedded within the folklore of Eurasia’.24 Although such enduring stories have been transmitted in words, they nonetheless raise the intriguing possibility that their resonance in the human psyche may echo muffled customs from the remote past. Within greater Eurasia is the Caucasus, where the intentional deposition of a cache of copper or bronze objects (a hoard), or a single item of metalwork not associated with any other artefact, is one of the most distinctive cultural practices of the Late Bronze–Early Iron Age period.Whether individual or multiple items, these depositions are usually found at some distance from a centre of population.The majority of hoards in the Caucasus have been discovered in western Georgia, where about 150 have been attributed to the Colchian culture.25

Elsewhere, some twenty Koban metal depositions have been found in the northern Caucasus, and even fewer (around thirteen) are associated with the Samtavro culture in the Shida Kartli region. Metal-hoarding is not unique to the Caucasus. In Europe, hoards are one of the most archaeologically visible features, yielding the majority of Bronze Age metalwork and totalling more than the items recovered from settlements and burials combined. Interestingly, hoarding is not a cultural characteristic found in the Near Eastern heartlands or Egypt, but it does occur in the eastern Mediterranean coastal lands, around the Persian Gulf and in northern Afghanistan.26 Further east, beyond the boundary of the Harappan province, metal hoards are a feature of the Doab, the fl at alluvial tract between the Ganges andYamuna rivers in northern India.27 Such sustained, expansive and large-scale hoarding is not a fortuitous incidence, and it differs in character from metal consumption in the urban centres of the Near East, where individual elite burials (an event) were the usual repository of precious items.

Items buried in the Colchian hordes are mostly metalwork, and share many similarities with those from the Koban.We need not discuss them again except to draw attention to the ‘Colchian axe’, the western Georgian counterpart of the Koban axe.These Colchian axes are found as part of hoards and also in graves with multiple burials (Ergeta). Although one or two have been found further east of the central Caucasus, the boundary of their geographical distribution can be drawn at Zhivali.28 The Colchian axe is distinctive in shape: a semi-circular blade, a long neck with hexagonal section, and an

24Wengrow 2010: 100.

25See also Apakidze 2000; Lordkipanidze 2001b.

26Wengrow 2010: map 6.

27Yule 1997.

28Reinhold 2007: fig. 22, pls. 42–4, lists 94–106 (categories Ax C1–5, D1–D2).

460 |

A World Apart |

elongated shaft-hole.This combination of features produced a series of ridges along the neck. Like the Koban type, the earliest examples, from Pilenkovo and Korochi, are thick and stubby, and date to the Middle to Late Bronze transition. Gradually, the neck lengthened but never developed the sinuous profile of the Koban variety. In profile, the Colchian axes are often asymmetrical, with accentuated shaft-hole ends. Many Colchian axes are distinguished by elaborate incised designs that cover their whole surface;29 most favoured are geometrical and fantastical animals skilfully accommodated on the blade.

So, then, how can the practice of metal hoarding be explained? An early interpretation of the Caucasian (and European) hoards saw them as property buried in a hurry, most likely in times of crisis, and thereafter never retrieved.30 Given the scale of this practice, such an explanation is no longer plausible. Generations of European archaeologists have debated this phenomenon and have come up with a number of interpretations, which generally fall into four broad models: utilitarian, economic, personal, and ritual.31 There is also a general consensus that collections of multiple objects, especially those deposited over a long period of time, represent the act of a community, whereas single items represent the activity of an individual.

Hoards are assigned to one of the four models based on either their character or the geography of the find spot. Pits filled with scrap metal – miscast, well-worn, or accidentally broken items – are generally viewed as ‘smiths’ hoards’, utilitarian in nature, which were buried for security and in readiness for recycling. Support for such an idea is provided by the accoutrements of metalworking sometimes found in these depositions – crucibles, moulds, waste metal, and ingots – as well as the careful sorting of metal types into lots. These metalsmiths’ hoards were buried in dry-land areas where they could be retrieved. Different are those caches that have multiple copies of the same item, or unused objects, buried not long after they had been manufactured. Such collections are seen as having once belonged to traders (‘merchants’ hoards’), who concealed the items in an accessible place, but for whatever reason never reclaimed them. So, these are interpreted in economic terms. Personal hoards are different again. They incorporate single item finds, generally reflecting individual ownership, such as a piece of jewellery (pin, bracelet or a fibula), or a set of tools.

Finally, there are hoards that comprise many different kinds of objects. Large and small, elaborate or plain, these valuable items are thought to have once belonged to a community that, over a lengthy stretch of time, threw them into a bog, river or lake, never to be retrieved.These ‘sacrificed’ or votive items are interpreted as part of a ritual process whereby the community gained social

29Koridze 1965; Pantskhava 1988; Skakov 1998.

30Koridze 1965.

31Bradley 1998, 2013; Harding 2000: 352–68.

Ceramic Production |

461 |

and political clout through the destruction of precious objects. This model of wealth consumption draws its inspiration, in part, from the same notion as potlatch, a gift-giving feast of the indigenous peoples of northern America. In this essentially economic system, a chief would display his power to a guest by giving away or destroying goods. In turn, in order not to diminish the leader’s power, the guest was required to reciprocate 100 per cent of the gifts and destroy more wealth.This process of conspicuous and public consumption would continue until one of participants was no longer able to reciprocate.32

CERAMIC PRODUCTION

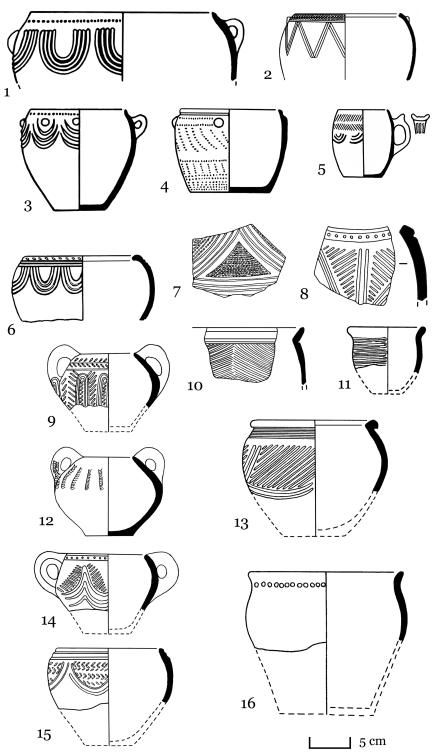

Proto-Colchian I pottery is handmade and represented mainly by two broad ware types.33 One has a fine biscuit, grit temper and polished black surface, whereas the other is thick-walled with a coarse fabric. Both are well represented at a number of sites, including the earliest level at Dablagomis Nazichvara.Typical vessels for the early stage of Proto-Colchian I are jars with cylindrical bodies, bowls with out-turned rims, and large jars with massive bases, sometimes decorated with fl ax or plant prints (Figure 10.3(1–3, 8, 11, 13, 16)). Only a small part of the pottery is decorated. New features appear towards the end of the Proto-Colchian I – conjoint and horizontal handles, and blackpolished containers with lentoid handles. Mat impressions peter out by this stage. Predominant forms of ornamentation are finger-impressed relief bands and intricate geometric patterns. Features continue to evolve in the ProtoColchian II period, especially in handles. Surfaces are still black polished with finger marks, but are less refined than those of the preceding period.

Late Bronze Age (Ancient Colchian I) pottery developed directly out of Middle Bronze Age (Proto-Colchian II) wares, a transition documented at several sites, including Pichori (Level IV), Anaklia (Level II) and Nosiri (Figure 10.3(4–5, 7, 9–10, 12, 14, 15)). The fabric is still coarse and poorly fired to a black, grey, or dull red-brown colour. Forms are initially limited in range. Generally speaking, Ancient Colchian I pottery is distinguished by a tendency towards increased and elaborate decoration.34 Decoration is mostly restricted to the upper half of the vessel, including the rim, and occasionally defined by a row of decoration or a groove, though a good number of containers are ornamented all over. Incised semi-circles, either pendant from a decorative band or unattached to other motifs, usually placed at the shoulder, are a common element. Potters also use comb-stamped ornaments (a hallmark of Pichori

32On the anthropological theory of values, see Graeber 2001, who revisits Marcel Mauss’ ideas on potlatch.

33Jibladze 1997: 71–8.

34Apakidze 2008.

Figure 10.3. Proto Colchian ceramics: (1–3) Anaklia; (6) Pichori; (8, 11, 13, 16) Mamuliebis Dikha-Gudzuba. Late Colchian: (4, 5) Anaklia; (7, 9–10, 12, 14, 15) Mamuliebis Dikha-Gudzuba (after Papuashvili and Papuashvili 2008;Apakidze 2008).

462

Ceramic Production |

463 |

Level III) and plastic knobs of varying size that are now found alongside oblique rows of notches, herringbone patterns, and wavy lines. Relief ornamentation is rare and usually confined to rather crude wavy lines. The last phase of the Ancient Colchian I assemblage witnessed the appearance of elements that foreshadowed the Early Iron Age: broad vertical flutes, and ‘zoomorphic’ handles that are essentially a horned version of a spur handle.

In the Early Iron Age (Ancient Colchian IIA), wheel-made pottery is introduced in small quantities and baked to the same low, reducing temperatures as handmade vessels – black, grey, and red-brown are still the predominant colours. Surface treatment is on the whole duller, and only rarely are vessels given the polish that distinguishes the earlier periods. The range of forms is more diverse than in earlier centuries, possibly suggesting a change in cuisine. Gone are hemispherical bowls, and containers with rounded shoulders and inward curving rims are few and far between. Jars and pots now have out-turned mouths with rims that can be sharply profiled. The neck, too, is pronounced, with simple horizontal grooves or even a band of rilling.

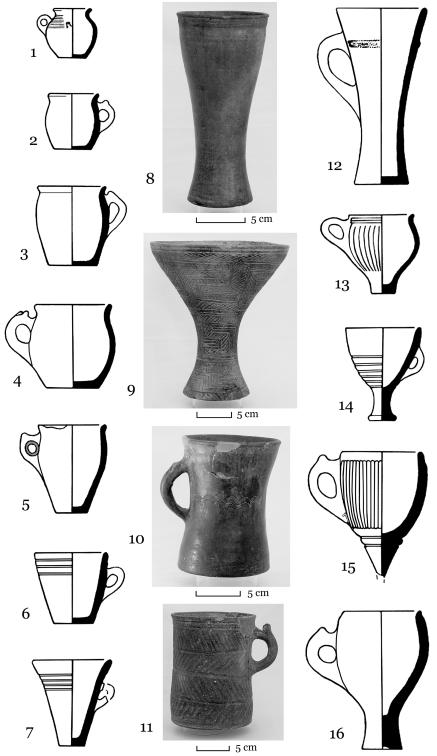

A widespread drinking culture is conspicuously reflected during the eighth and seventh centuries in the range of drinking beakers (Figure 10.4). A new and distinctive form is the vertically fluted beaker with a pointed base, and a handle boasting a pair of horns. Bold fluting is not a local form of decoration and its introduction is sought in connections with Bulgaria and the Aegean.35 Another novel motif is rows of running spirals. Otherwise, comb-stamped designs and bands of geometric patterns (herringbone, notches, net designs, and wavy lines), now executed with more fl are and refinement, continue to appeal.

Potters of the eighth century BC (Ancient Colchian IIB) rarely built containers by hand – they now almost always used the wheel. They also had little time for polishing their wares, which are rather coarse to touch and in fabric. Ornamentation became simpler. A greater and swifter production of pottery overshadowed the traditional and time-consuming attention to fine detail.The last phase, the seventh century (Ancient Colchian IIC), is distinctive in many respects. Not only does the quantity of pottery increase, so too does the range of forms, with potters embracing many new shapes. Form takes primacy over decoration.This proliferation of shapes is best reflected in the number and variety of drinking vessels. Although traditional mugs and beakers with round profiles continue, we now have a range of tall drinking tankards, often supported on a stump base. Other new forms include highshouldered jars and handled jugs. If vessels are ornamented, they are usually fluted vertically or have a few discrete horizontal lines to highlight specific parts of the vessel.

35 Apakidze 2009.

464 |

A World Apart |

Figure 10.4. Principal types of ancient Colchian drinking beakers 800–600 BC; no. 9 is from Samtavro (after Apakidze 2008, photographs A. Sagona).

Colchis and Koban: TheYin andYang of the Caucasus? |

465 |

COLCHIS AND KOBAN: THE YIN AND YANG OF THE

CAUCASUS?

The relationship between Colchis and Koban in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age is a contentious subject. Were they the same cultural complex, or are we dealing with two separate communities that had a close cultural relationship? There is much to recommend the view that, like the principle of yin and yang, Colchis and Koban were complementary forces that interacted to form a dynamic system in which the whole was greater than the assembled parts.

At the core of this matter is the striking resemblance between certain metal objects from western Georgia and the northern Caucasus, such as highly ornate axes, which at the very least display a tradition of sharing technological ideas and artistic trends.36 First raised in the early twentieth century, this deliberation shows no signs of abating.37 Numerous studies have created a web of regional interconnections, some tight and others diaphanous, in an attempt to evaluate this relationship.38 But metallurgy and metalwork are not the only features the two regions had in common.The view that Colchis and Koban is a unitary archaeological culture has also focused on burial architecture, funerary rites, and even ceramics. Close examination of the evidence, however, does not bear this out. Moreover, there are clear-cut differences in economic practices and modes of architecture and settlement patterns (usually dismissed in terms of a rather inadequate environmental determinism – different climate means different settlements) that support the separation of the two.39

Burial practices in western Georgia and the northern Caucasus have often been seen as too diverse to distinguish regional differences, and so they have been lumped together as a common feature. But, as Gobejishvili has noted, while the two culture provinces do exhibit similarities in modes of mortuary traditions, both have a number of customs that are not shared. Four tomb types (graves with a stone layers and ringed with stones, graves with a timber structure, collective burials, and ossuaries) are found only in Colchis, whereas burial vaults and cromlechs are prevalent only in the Koban region.The rest of the burial types are common to both regions. But, even then, they do reflect discrepancies.40

36Voronov (1984: 10) discerns twelve regional variants of the Colchian-Koban metallurgical province: Colchis (central, northern, and southern); the south-eastern and north-eastern Black Sea areas; Racha-Lechkhumi-Svaneti;Tli cemetery; Samatvro cemetery; and the Koban (central, eastern, western, and upper) province. In a recent study, Apakidze (2009) slices up this metallurgical province into three regions: the northern Caucasus, western Georgia, and north-western Shida Kartli.

37For an early discussion, see Ivascenko 1932.

38A historical summary of this debate can be found in Apakidze (2009: 12–23).

39Voronov 1984: 11.

40Gobejishvili 2014.

466 |

A World Apart |

For a start, circular earthen pits are not known from the northern Caucasus. And while inhumation is by far the preponderant mode of burial in that region, in Colchis, especially in the western part of the province, many people were cremated and their ashes placed in earthen pit tombs. In the northern Caucasus, cremation was never associated with simple earthen pits. Another marked difference concerns secondary burial in simple pits: this rite was practised in Colchis (for example at Gagra and Ureki), but never in the northern Caucasus. Inhumations in a simple pit also show variability. Both regions generally laid the dead to rest in a flexed position. In the eastern part of the Koban culture there was differentiation according to sex – males were placed on their right sides, females on their left. Broadly speaking, this rule was also applied at Tli. But on the whole, neither the communities of Colchis nor those in the northern Caucasus adhered to hard and fast rules in relation to position.

Earthen pits sealed with a layer of stones are another shared tomb type, but there are more differences than commonalities between the two regions. While the funerary rite of burning the body within the pit is recorded at both Khutsubani (Colchis) and Kumush (northern Caucasus), the excavators argue they are not contemporary sites, though it should be noted that we have no radiocarbon dates. Khutsubani is assigned to the early centuries of the first millennium and Kumush to a later date, making it difficult to draw inferences based on commonality. Rites associated with tombs from both regions that are sealed with stones are associated with funerary feasts, as clearly shown by the quantity of animal bones found in the pits.

Cist tombs are a feature of both Koban and Colchian cultures, but they are far more common in the north-central Caucasus. Inhumation in a flexed position is the norm in both cultures, with no rigid rules on orientation; the deceased were never placed on their backs.

Barrows are more common in the northern Caucasus than in western Georgia, where only one site (Goradziri) is documented.Their appearance in the Koban culture is late, about 750 BC, and generally assigned to Scythian influence. Whether they represent political and economic connections or possibly a movement of people, is not altogether clear. There is no question that syncretism occurred – it is seen in the novel idea of covering local modes of burial architecture with barrows of earth – but whether this is part of an acculturation process of new groups or simply a transfer of ideas remains to be seen.

Earthen pit burials defined by a row of stones around the edge are rare in both cultures, chronologically not coeval, and spread across quite different environments. The west Georgian versions are earlier than those in the northern Caucasus and also differ in the way the dead are laid in a supine position.

Gobejishvili correctly argues that the currently restricted data on cremation rites, geographically dispersed and chronologically expansive as they are, do not