- •Contents

- •Illustrations

- •Acknowledgments

- •Prologue

- •1. The Sumerian Takeoff

- •Natural and Created Landscapes

- •A Reversal of Fortune

- •Forthcoming Discussions

- •The Material Limits of the Evidence

- •Conceptual Problems

- •Methodological Problems

- •Growth As Specialization

- •Growth Situated

- •Growth Institutionalized

- •4. Early Mesopotamian Urbanism: Why?

- •Environmental Advantages

- •Geographical Advantages

- •Comparative and Competitive Advantages

- •5. Early Mesopotamian Urbanism: How?

- •The Growth of Early Mesopotamian Urban Economies

- •The Uruk Expansion

- •Multiplier Effects

- •Flint

- •Metals

- •Textiles

- •6. The Evidence for Trade

- •Evidentiary Biases

- •Florescent Urbanism in Alluvial Mesopotamia

- •The Primacy of Warka: Location, Location, Location

- •Aborted Urbanism in Upper Mesopotamia

- •8. The Synergies of Civilization

- •Propinquity and Its Consequences

- •Technologies of the Intellect

- •The Urban Revolution Revisited

- •Agency

- •Paleoenvironment

- •Trade

- •Households and Property

- •Excavation and Survey

- •Paleozoology

- •Mortuary Evidence

- •Chronology

- •The Early Uruk Problem

- •Notes

- •Prologue

- •Chapter One

- •Chapter Two

- •Chapter Three

- •Chapter Four

- •Chapter Five

- •Chapter Six

- •Chapter Seven

- •Chapter Eight

- •Chapter Nine

- •Epilogue

- •Reference List

- •Source List

- •Figures

- •Table

- •Index

EARLY MESOPOTAMIAN URBANISM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE |

109 |

may not be missing at all, but rather may have abandoned settled life to became pastoral nomads in response to growing alluvial demands for wool, as Kouchoukos and Wilkinson (2007, 18) have argued. While this is quite possible, it is also likely that immigration from peripheral areas losing settled population fueled—at least in part—the urbanization of the Mesopotamian alluvium through the Uruk period.

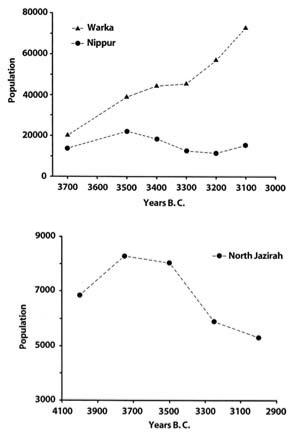

This brings us to the second and third noteworthy points that emerge from Kouchoukos and Wilkinson’s work—that in absolute terms the population of the Mesopotamian alluvium throughout the various phases of the Uruk period was substantially greater than that of any one coherent area of the Mesopotamian periphery at the time, and that relative population densities in southern Mesopotamia during the Uruk period were also higher than those typical for contemporary polities in neighboring regions.5 Starting with the former point, after recalibration under a single standard, the data marshaled by Kouchoukos and Wilkinson indicate that as many as 100,000 people lived within the main surveyed portions of the southern Mesopotamian alluvium during the final phase of the Uruk period (fig. 16). This contrasts sharply against the 6,000 or so people documented by Wilkinson as inhabiting the surveyed portions of the north Jazirah plains at this time. Presuming that Wilkinson’s data is roughly representative for conditions in Upper Mesopotamia as a whole (an admittedly risky assumption that can only be tested once the results of the more recent surveys around Tell Brak are fully analyzed and published), and correcting for the overall 10:1 difference in survey extent between the two areas (roughly 5,000 square km for southern Iraq versus 500 square km for the north Jazirah plains), population density per square kilometer in the alluvium was just under double that prevalent in the Upper Mesopotamian plains. However, this estimate likely substantially understates the true difference in the demographic density between the two areas because of sharply depressed site counts in the south arising from the alluvial and aeolian deposition processes discussed earlier.

The Primacy of Warka: Location, Location, Location

The extraordinary growth of Warka and its immediate hinterland in the Late Uruk period demand explanation. Writing separately, Kent Flannery (1995) and Joyce Marcus (1998) both suggest that Warka would have been the capital of a territorial empire in the Late Uruk period, which

110 |

CHAPTER SEVEN |

fiGURE 19. Fourth-millennium demographic trends in surveyed portions of the Warka and Nippur-Adab areas of southern Mesopotamia, and surveyed portions of the North Jazirah region in northern Iraq.

presumably would have encompassed not only the whole of the alluvium but also, at this time, colonized areas of southwestern Iran and, possibly, portions of northern Mesopotamia, such as the Euphrates Bend. Flannery and Marcus explicitly assume that all pristine states emerge from a crucible of conflict as earlier regional chiefdoms are consolidated by force into a single overarching polity, and they presume the same to have been the case at the onset of Mesopotamian civilization. As supporting evidence, they point to the four to fivefold size differential (below) that current data suggest existed between Warka and its nearest second-tier settlements in the alluvium during the Late Uruk period.

EARLY MESOPOTAMIAN URBANISM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE |

111 |

This is a plausible interpretation of the evidence we possess at this time, which, regretfully, aside from excavations at Warka, consists mostly of surface survey data. Equally possible at this point, however, are interpretations that acknowledge the importance of intraregional conflict as a mechanism promoting early Mesopotamian state formation and urban agglomeration but that see warfare as a consequence of more deeply rooted processes of asymmetrical growth initially set into motion by the already noted multiplier effects of trade. From this perspective, Warka and the various other cities that existed throughout the surveyed portions of the Mesopotamian alluvium and neighboring plains of southwestern Iran in the Uruk period developed in tandem and would represent the centers of independent polities of varying extent and power ancestral to the competing city-states that characterized the alluvium throughout much of its history.

Of these interpretations, I believe the latter (trade-fueled asymmetrical growth leading to coevolving polities of varying size) is the one that best fits available data for three principal reasons. The first is that existing size differentials between Warka (250 ha) and its nearest second-tier settlements (site 1306 at 50 ha) may well reflect nothing but an accident of discovery. Indeed, two facts raise the possibility that Warka and the other known Uruk urban sites in the surveyed portions of the alluvium represent only the visible tip, so to say, of the Uruk period settlement iceberg in southern Mesopotamia as a whole. First, as already noted, geomorphologic processes operating in the southern alluvial plains of Tigris and Euphrates rivers are particularly likely to obscure a large proportion of the smaller Uruk period sites in the south. In addition, in places, particularly dense Late Holocene alluvial deposits may even obscure some of the larger Uruk sites in the south. This possibility is raised by J. Pournelle (2003a, 2003b, 194, 247–48), who notes that, in some cases, satellite imagery shows that multiple small nearby Uruk period sites recorded by Adams as independent settlements could have been instead parts of much larger, contiguous shallow settlements partly covered by alluvial deposits (e.g., site 125; see Pournelle 2003b, fig. 80). Second, and more concretely, it should be remembered that much of the eastern portion of the Mesopotamian alluvium centered on the Tigris was never systematically surveyed because of the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq war (Robert M. Adams, personal communication, 2003). A number of sites exist in these still (systematically) unexplored areas that were occupied during one or more phases of the Uruk period. These sites are not considered in recent

112 |

CHAPTER SEVEN |

reviews of the nature of Uruk period settlement in southern Mesopotamia (e.g., Algaze 2001a; Pollock 2001; Wilkinson 2000b), but several are likely to have been quite substantial at the time.

Foremost among these are Umma and the nearby site of Umm alAqarib.6 During a recent brief visit to Umma, McGuire Gibson (personal communication, 2001) reports Uruk period pottery spread widely over the surface of the site. More tellingly, numerous Archaic Texts recently plundered from either (or both) of those sites appear immediately comparable to the earliest examples from Warka (Englund 2004, 28, n. 7). At a minimum, these tablets attest to the economic importance of the Umma area in the Late Uruk period. However, since at Uruk these tablets are part of a wider urban assemblage of great extent and complexity, their presence in the Umma area argues for a similar context. Though circumstantial, this evidence suggests that Umma and its satellites may have been second only to Warka itself in terms of urban and social development in the Late Uruk period.

Buttressing this possibility is a glaring anomaly in the settlement data for Late Uruk southern Mesopotamia as presently known (table 1; app. 2): the largest site (Warka) is just over four times as large (i.e., populous) as second-tier settlements, which in the Late Uruk phase fall in the 50-hect- are range (Tell al-Hayyad [site 1306]). This is anomalous because analyses of modern urban systems show that urban populations commonly arrange themselves in rank order by size in predictable ways (“Zipf’s Law”), so that as the cumulative number of settlements falls by a given multiple, for example, by half, the site sizes typical for the immediately succeeding settlement tier increase roughly by that same multiple, for example, double (Krugman 1996b). In Zipf’s terms a settlement at rank x is roughly 1/x the size of the largest settlement. If comparable rank-size behavior characterized the ancient Mesopotamian urban world, then existing 50-hectare-range second-tier sites would represent instead a third tier of Late Uruk settlement in southern Mesopotamia. By this logic, the second tier of that settlement system then would have been anchored by a site or sites roughly half the extent (i.e., population) of Warka, as can be observed in table 1. I expect that Umma and its immediate satellites will eventually be found to represent this missing tier and that further work at the site will eventually show it to have been somewhere in the range of 100–120 hectares in the Late Uruk period.7

Be that as it may, a variety of other important alluvial sites are further candidates for significant Uruk period sites or site complexes outside of

EARLY MESOPOTAMIAN URBANISM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE |

113 |

TABLE 1. Reworking of Adams’s (1981, table 7, see appendix 2 below) data for Late Uruk period settlement in the Nippur-Adab and Warka regions according to Zipf-derived rank-size rules

|

Recorded |

|

Expected |

Observed |

Category |

Size Range (ha) |

Average |

Number |

Number |

|

|

|

|

|

“Hamlets” |

0.1–2.4 |

1.56 |

52 |

69 |

“Villages” |

2.5–4.9 |

3.125 |

26 |

31 |

“Small towns” |

5–9 |

6.25 |

13 |

16 |

“Large towns” |

10–14 |

12.5 |

6.5 |

6 |

“Small cities” |

24–25 |

25 |

3.25 |

3 |

“Cities” |

50 |

50 |

1.625 |

1 |

“Large cities” |

|

100 |

0.81 |

0 (Umma?) |

“Primate city” |

200 + |

200 + |

0.4 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Douglas White (UC, Irvine) kindly helped in the preparation of this figure.

the present boundaries of systematic survey in the south. One such site is the Early Dynastic city of Adab, excavated by a U.S. expedition early in the twentieth century that was covered by sand dunes in the 1960s and 1970s, when the area surrounding the site was surveyed (Adams 1981, 63). While no archaeological evidence for the Uruk period is known from the haphazard excavations conducted at the site, it is certain that an important settlement existed here at that time, because Adab figures prominently among the toponyms found in the earliest group of Archaic Texts (Uruk IV date). In fact, of a total of 24 recognizable geographic names in those tablets, Adab is mentioned 8 times, or a full 33 percent of the references (for comparison, as Potts [1997, 29] notes, Uruk itself is mentioned ten times in the texts). Other candidates for significant Uruk settlements are Girsu, where French excavations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries uncovered substantial Uruk period remains (Parrot 1948), and the smaller site of Surghul, downstream on the ancient Tigris, where Uruk deposits also exist (E. Carter, personal communication, 2001). Both times are situated entirely outside the areas systematic surveyed by Adams and his colleagues. Because both Girsu and Surghul were central settlements in the later third-millennium kingdom of Lagash, it is not farfetched to suggest that they formed parts of a smaller earlier polity of the Uruk period in the same region.

A second reason why political balkanization rather than centralization is a more likely description of conditions in the Mesopotamian alluvium and related areas in the Uruk period as a whole is that processes of urban growth throughout the period appear to have resulted in the creation

114 |

CHAPTER SEVEN |

of clear buffer zones between some of the emerging settlement centers of the time. The clearest instance of this pattern is that documented by Gregory Johnson for the Susiana Plain, an area not considered by Pollock in her proposal for the political structure of the early Sumerian world of the Uruk period but that, as noted in the prologue, appears to have been colonized by Mesopotamian populations relatively early in the Uruk period. Johnson’s (1987, 124) surveys document the abandonment of all Middle Uruk period villages along a 15-kilometer-wide arc by the Late Uruk period, separating what by then appear to have been two rival early Sumerian statelets centered at Susa and Chogha Mish, respectively. This clear “buffer zone” indicates that these centers were independent from each other. More likely than not, they were independent from contemporary centers in the alluvium as well.

A further buffer area may perhaps be recognized in the widespread abandonment of villages along a broad arc between Abu Salabikh and Tell al-Hayyad at the transition between the earlier (Early/Middle) and later (Late) phases of the Uruk period as delineated by Adams (compare Adams 1981, figs. 13 and 12, respectively). This area of abandonment is situated between the northernmost (Nippur-Adab) and southernmost (Uruk) surveyed portions of the alluvium. Adams (1981, 66) has interpreted this arc as given over to pasture lands and foraging activities, and notes that important river course changes took place here that may have made the area uninhabitable by agriculturalists and thus contributed to the observed population shift. While this is almost certainly correct, it does not in any way exclude the possibility that the uninhabited arc between Abu Salabikh and Tell al-Hayyad could also reflect a politicalmilitary buffer between competing alluvial polities in the Late Uruk period.8

Finally, it is also possible that the primacy of Warka reflects a religious rather than a political paramountcy. This explanation, which is fully consistent with the reconstruction of the Mesopotamian alluvium in the fourth millennium as a politically fractious but culturally homogeneous landscape, was recently proposed by Steinkeller (1999), who argued that Uruk may have functioned as the religious capital of Sumer through the Uruk and the succeeding Jemdet Nasr periods. This assessment is based on a handful of Jemdet Nasr period tablets (Uruk III script) from Jemdet Nasr, Uqair, and Uruk that show that individual Sumerian cities were sending resources (including various types of foodstuffs and slave women) to Uruk as ritual offerings to Inanna, one of the city’s chief dei-

EARLY MESOPOTAMIAN URBANISM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE |

115 |

ties. Steinkeller suggests, plausibly, that this situation reflects a continuation of conditions that must have started already in the Uruk period and that it represents, in turn, the precursor of the already noted bala taxation and distribution system that would later keep the religious institutions of Nippur and nearby cities supplied with necessary offerings and resources at the very end of the third millennium, during the Ur III period.

Steinkeller’s hypothesis represents, in effect, an elaboration of a much earlier suggestion by Adams (1966), who argued that, whatever other factors may have been at work, early Mesopotamian cities also ultimately coalesced around preexisting centers of religious pilgrimage. Both views help account for the possibly quite unusual scale of religious architecture uncovered by German expeditions at the center of Warka, both in the Eanna Precinct (e.g., the “Stone Cone Mosaic” Temple [Eanna VI], the “Limestone” Temple [Eanna V], and “Temples C” and “D” [Eanna IVa]; fig. 3) and in the Anu Ziggurat area (e.g., the “White” Temple and the even larger “Stone Building,” which Forest [1999] argues was also a temple; fig. 2). Both views also help to account for the wealth of precious imports found at the core of Uruk, many of which may have been brought in as votive offerings.

It should be noted, however, that even if Steinkeller and Adams are correct about the religious underpinnings of Uruk’s centrality in the fourth millennium, their arguments need not necessarily be interpreted to mean that Warka was the political capital of a unified “national” state in the Uruk period. While in many early civilizations political control is often coterminous with religious paramountcy, this correlation is by no means absolute. Nowhere is this clearer than in Mesopotamia itself, where Nippur was the acknowledged religious capital of the alluvium throughout the third millennium without ever being the seat of a political dynasty.

Plausible as religious centrality may be as an explanation for Warka’s preeminence through much of the Uruk period, the fact remains that available survey and excavation data from southern Mesopotamia remains entirely too ambiguous to allow for a detailed reconstruction of either the political or the religious landscape of southern societies at the time. Nor, given the nature of the evidence, is it within our power to reconstruct specific sequences of self-aggrandizing actions by particular individuals and institutions that may have contributed to that preeminence. What we can do, however, is outline the framework in which such actions would have been likely to take place and in which, once they did, they would

116 |

CHAPTER SEVEN |

have been likely to succeed. No doubt, that framework owes much to the site’s location. Like other fourth-millennium alluvial centers, Warka was located at the bottom of the huge transportation funnel created by the Tigris-Euphrates watershed. However, as Jennifer Pournelle (2003a, figs. 7a, 8) has recently noted, the site was also situated precisely at the point where the main channel of the Euphrates, as it existed in the fourth millennium, broke (and/or was channeled) into a corona of smaller distributaries as the river reached the then receding mid-Holocene Persian Gulf coastline. The resulting radial patterning of water channels partially encircling Warka (figs. 5, 21) allowed its inhabitants an ease of access, via water transport, to resources, labor, and information drawn from both the site’s immediate hinterland and the vast Tigris-Euphrates watershed that was unmatched by neighboring polities in the alluvium and entirely unachievable by contemporary polities outside of the alluvium.

In fact, as predicted by the core premises of the new economic geography (chap. 3), differential transport costs alone might well account for the seemingly monocentric urban structure of the Warka area in the Middle–Late Uruk period versus the more multicentric character of the Nippur-Adab area, a divergence recently highlighted in Pollock’s (2001, 218) reexamination of Adams’s survey data.9 The fact is that however privileged they may have been in terms of their access to waterborne transport in comparison with nonalluvial polities, cities in the northern reaches of the Mesopotamian alluvium did not possess the natural radial channels that surrounded Warka at the time early Sumerian civilization crystallized in the second half of the fourth millennium. Nor, because of the slowly receding mid-Holocene coastline, did they have as extensive an area of navigable marshes in their immediate environs. Speaking in the abstract about the relationship between location, transportation, and development, sociologist Amos Hawley (1986, 90) has observed that “[l]ocation proves critical in the initiation of an expansion process. The strategic site is possessed by the center with the easiest access to both regional and interregional influences. It is there that the requisite information for improvements in transportation and communication technologies has the greatest probability of accumulating.”10

Hawley’s insights apply not only to the specific case of Warka but also more broadly to the Mesopotamian alluvium as a whole. How farsighted those insights really are in terms of the explanation of the Sumerian takeoff will become clear in the chapter that follows. Before proceeding to that assessment, however, we must take a few moments to contrast the