- •Isbn-10: 1-4338-0549-9

- •Introduction

- •The Palo Alto Team

- •Murray Bowen

- •Salvador Minuchin and Structural Family Therapy

- •Strategic Family Therapy

- •Solution-Oriented Therapy

- •Narrative Therapy

- •Psychoeducation Family Therapy and Medical Family Therapy

- •Multisystemic Therapy

- •Multidimensional Family Therapy

- •Figure 3.1

- •Figure 3.1 (Continued)

- •The Patient’s Symptom as a Function of Unresolved Family Issues

- •Figure 4.1

- •The “Patient” in Family Therapy

- •Two Against One: Triangulation and Intergenerational Coalitions

- •The Pursuer–Distancer Dance

- •Collaboration and the Role of the Larger System

- •The Role of the Therapist

- •The Role of the Patient and Family

- •Goal Setting

- •Enactment

- •Circular Questions

- •Externalizing the Problem

- •Family Sculpting

- •Positively Connoting the Resistance to Change

- •Genograms and Time Lines

- •Building on Family Strengths

- •Figure 4.2

- •Family Psychoeducation for Schizophrenia

- •Adolescent Conduct Disorders

- •Adolescent Substance Abuse

- •Childhood Behavioral and Emotional Disorders

- •Anorexia Nervosa in Adolescence

- •Alcohol Abuse in Adults

- •Interventions With Physical Disorders

- •Ideas and techniques that cut across models of family therapy

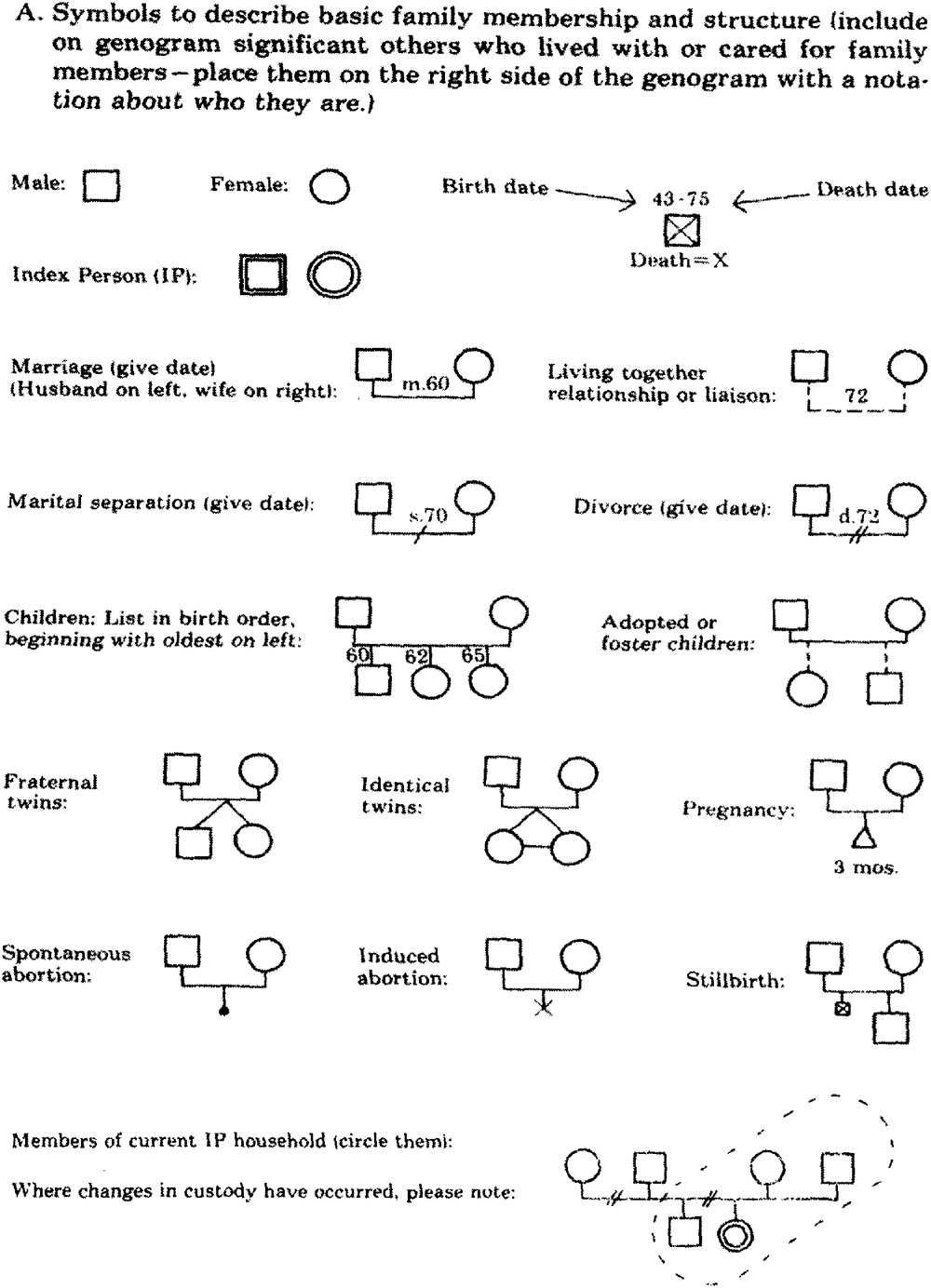

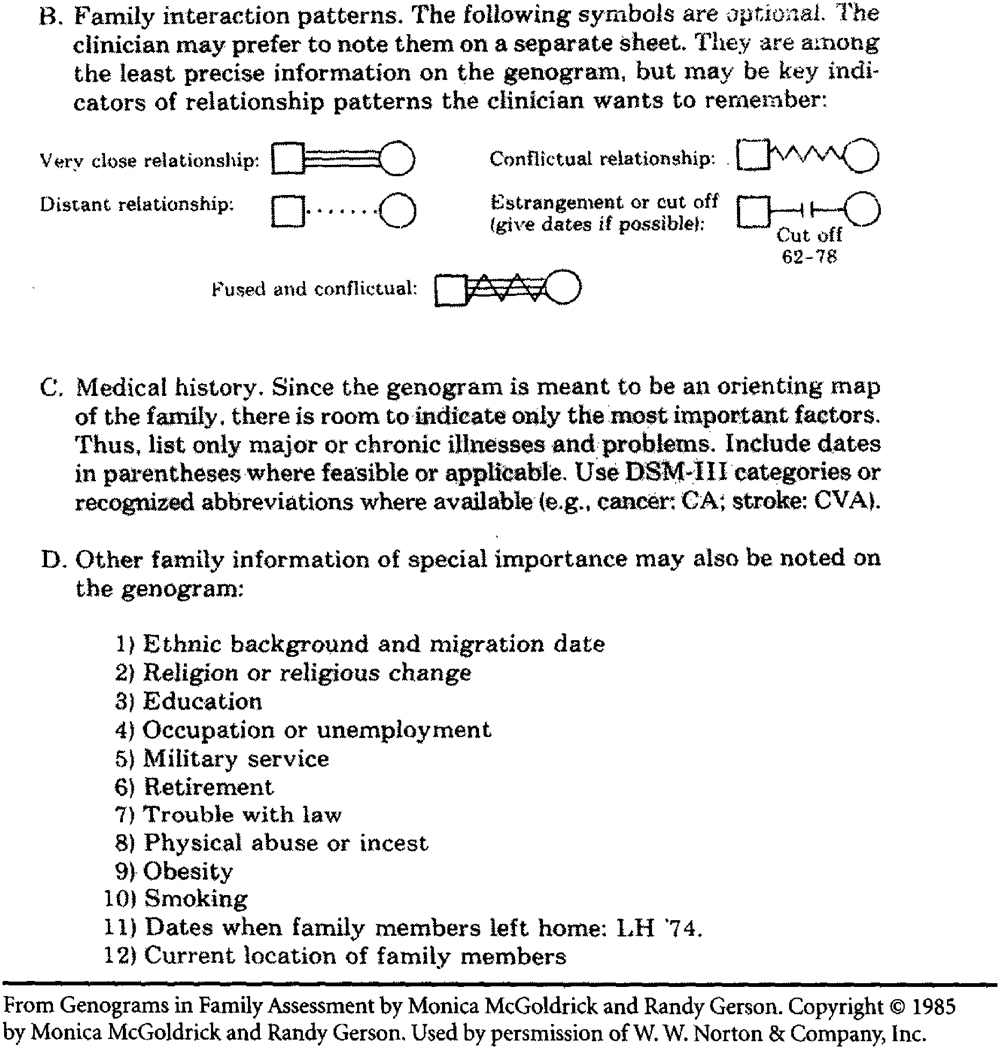

Figure 3.1

Genogram Format

Figure 3.1 (Continued)

CONCLUSION

Family therapy has a rich conceptual history going back to the mid-1950s and continuing to develop today. Pinning down these nuanced concepts in empirical research has been difficult, although progress has been made in the last two decades (see chap. 5, this volume). Many family therapy ideas cannot be fully grasped cognitively without experience seeing families in the therapy room or the home. A dance can be described in words, but it has to be seen in action with the music playing. The concept of triangulation becomes real to a therapist when you are sitting with a couple or family and feel yourself being inducted into a coalition of one family member against another—the very pattern the family members enact with one another at home. It can happen in an instant, as when you make an observation to one family member that another member jumps on with vigorous agreement, thereby angering the first family member who fights back against you and your observation. This becomes valuable experiential information as you work with the family.

Of course, the other way to internalize family therapy ideas is to examine one’s own family. In fact, experiential courses on family of origin are common in family therapy training programs, where trainees create their family genograms, investigate family history, interview relatives, and present their family story to their colleagues. We’re reasonably sure that readers have been thinking of their own family systems throughout this chapter. Indeed, our own families are in the room every time we meet with a family, so it’s a good idea to know where we are coming from!

Portions of this chapter are adapted from “Theories Emerging From Marriage and Family Therapy,” by W. J. Doherty and D. Baptiste, 1993, in P. G. Boss, W. J. Doherty, R. LaRossa, S. K. Steinmentz, and W. R. Schumm (Eds.), Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach (pp. 505–529), New York: Plenum. Copyright 1993 by Springer. Reprinted with permission.

![]()

The Therapy Process

With history and theory as a backdrop, this chapter describes the elements of family therapy and puts them into motion. It focuses on what family therapy looks like on the ground as a therapeutic approach and on how it changes individuals, families, and sometimes even professionals. As with other chapters in this book, we use a broad brush stroke to explain ways of working across the prominent models of family therapy.

APPLICATION OF FAMILY SYSTEMS THEORY

Family therapy can seem complex because of its attention to the many systems that contribute to who a patient is and with what he or she presents. We present here some examples of ways to apply family systems therapy as well as some illustrations of key concepts in the therapy process, such as triangulation and the dynamic of the pursuer–distancer in relationships.

The Patient’s Symptom as a Function of Unresolved Family Issues

Family systems theory is based on the idea that an individual’s symptoms are either a product of, or reinforced by, the interpersonal environment. Sometimes these patterns grow out of recent unresolved conflict; at other times they are the product of years, even generations, of problematic coping.

Consider this case example: Diana1 was 18 when she and her 2-year-old daughter, Donna, were brought to therapy by her Irish-American mother, Debra, and stepfather, Don. When asked the problem, Diana said: “I don’t know (nodding to her parents). They insist I come. I don’t have any problems. I just want to spend time with my friends.”

This answer provoked a strong response from her mother: “Diana, you gave up the chance to have an easy time of it when you got pregnant. You have a daughter now!” To the therapist, Diana’s mother said: “We didn’t ask for this. Diana got herself in trouble, and now she won’t pay her dues. All she does is party, and I, for one, am unwilling to do all the babysitting. We love our granddaughter, but we’ve already raised our children. We don’t have a lot of money, we can’t get help. Diana needs to stay home and take responsibility for this baby.”

Throughout this diatribe, Diana’s stepfather, Don, sat quietly. He had heard it before. At this point in the session, the therapist thought the problem was primarily related to developmental and family life cycle challenges: Diana was very young when she had a child, out of phase for her culture, and she was unequipped developmentally to handle her new role. She did not adapt to this new reality in her life but rather maintained her preferred status as a carefree teenager. Her parents, for their part, also did not want to adapt. They felt they were through with child rearing and wanted a less hands-on, grandparent-like role rather than the primary parenting role they inherited.

This explanation was interesting but somehow seemed superficial. The therapist drew a genogram (see Figure 4.1) on easel paper with the family. She asked Diana for the family history and learned that Diana’s biological father left her mother while her mother was pregnant with her. When the therapist asked for her father’s name, Diana said, “Bob,” but her mother looked surprised and interrupted, “No, honey, it was Fred.” Diana shrugged; she knew precious little about her biological father. He disappeared with the news of her mother’s pregnancy. Her stepfather, Don, began dating her mother soon thereafter, and they married just after Diana’s birth. Don was the only father Diana had ever known. As is typical, the therapist asked about Diana’s grandparents and the significant health events in the family. Diana quickly said: “Well, my father [Don] had a heart attack several years ago.”