- •Introduction

- •Figure 3.1

- •Figure 3.2

- •Figure 3.3

- •Figure 3.4

- •Figure 3.5

- •Exhibit 4.1 Principles of Cognitive Therapy

- •Focus on Current Adaptation and Present Problems

- •Time-Limited Treatment

- •Structured Therapy

- •Intrasession Structure

- •Intersession Structure

- •Key Roles of Activity and Homework

- •A Focus on the Therapeutic Relationship

- •Collaborative Empiricism

- •Psychoeducation

- •Technical Eclecticism

- •Treatment as Prevention

- •Intake Assessment

- •Case Conceptualization

- •Figure 4.1

- •Figure 4.2

- •Socializing the Patient to Treatment

- •The End of the Beginning

- •Assessment of Automatic Thoughts

- •Table 4.1 Common Cognitive Distortions

- •Figure 4.3

- •Figure 4.4

- •Working With Automatic Thoughts

- •Intervening With Automatic Thoughts

- •Evidence-Based Interventions for Automatic Thoughts

- •Alternative-Based Interventions

- •Figure 4.5

- •Developing Positive Thoughts

- •Meaning-Based Interventions

- •Figure 4.6

- •Schema Assessment

- •Ethics of Schema Change

- •Schema Interventions

- •Figure 4.7

- •Figure 4.8

- •Acceptance and Cognitive Therapy

- •Figure 4.9

- •Limits of the Model

- •Failure, Relapse, and Recurrence

- •Sociocultural Adaptations and Diversity Considerations

- •Training and Dissemination

- •Evidence-Based Interventions for Automatic Thoughts

- •Alternative-Based Interventions

- •Developing Positive Thoughts

- •Meaning-Based Interventions

- •Working With Core Beliefs and Schemas

Assessment of Automatic Thoughts

Various methods can be used to collect information about automatic thoughts. If the thought is relatively simple and repetitive, recording its frequency might be sufficient. In such cases even something as simple as a golf counter can be used to collect frequency information. The thought can be monitored and may become less frequent as it is challenged over the course of therapy. If the thought is more complex, the patient may maintain a small notebook or ledger in which he or she can record the thoughts. The actual content of the thought thus can be examined and may change over the course of treatment. The following presents a brief interaction between therapist and patient, which illustrates how a cognitive therapist might try to orient a female patient to the role that negative automatic thoughts play in emotional distress:

Patient: I had a real fright last night, when my ex-husband called and said our son was hurt.

Therapist: What happened?

Patient: Nothing much really, but when he called he said that Nicholas, our son, had been in an accident. My first thought was that he was dead or at least in the hospital, the way he said it.

Therapist: So you quickly jumped to the worst possible thing?

Patient: Yes, that happens pretty often. But then when I found out that he had only cut himself at the playground I thought that maybe my ex was just putting things in a dramatic way to get me going. He is like that.

Therapist: I take it that you have other experiences with him where maybe he tried to get you upset?

Patient: Yes, whenever I talk with him now, I am always on my guard.

Therapist: So, in this case you both had a tendency to hear the worst about your child and to imagine the worst about your ex-husband! It’s probably not too surprising that you had a real fright.

As noted in the last section, cognitive therapy often has an educational aspect. In some cases it is appropriate to directly instruct the patient about the cognitive model and to explain the relationships among beliefs, triggers, automatic thoughts, and the emotional and behavioral consequences of negative thoughts. Some patients may want to read more about the process, and the therapist can assign a workbook such as Mind Over Mood (Greenberger & Padesky, 1995) or a text such as Reinventing Your Life (Young & Klosko, 1994). Furthermore, patients can be instructed about the various types of negative thoughts related to distress and the various forms of distortions. If it seems appropriate and the patient is interested, he or she can be provided with a list of common cognitive distortions (see Table 4.1). Some patients enjoy discussing how their experience can be biased by distortions that fit with core beliefs, and some patients even enjoy identifying their own distortive tendencies as a kind of investigative process.

Table 4.1 Common Cognitive Distortions

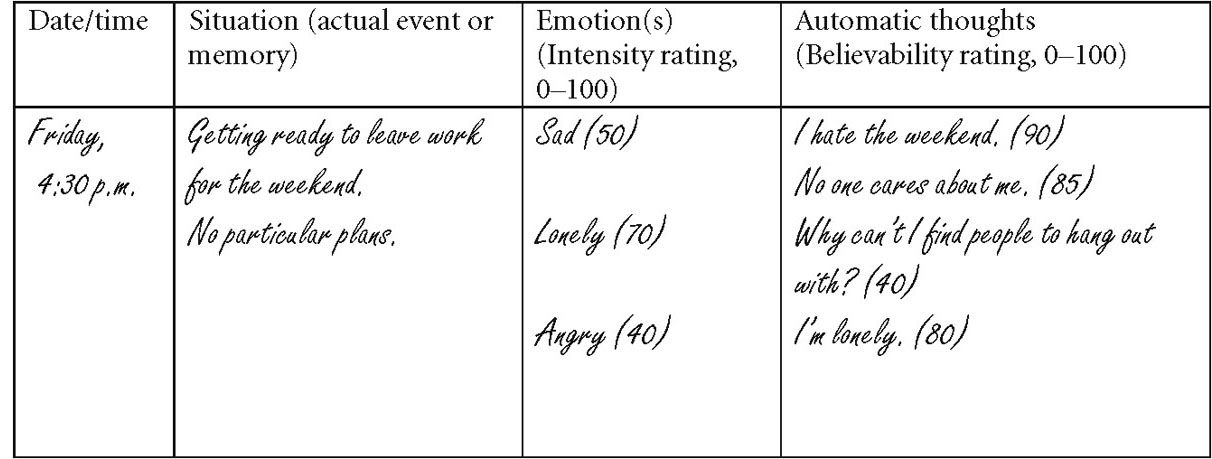

The content of the thought, the context in which it arises, and the consequences of the thought are important. Thought records are commonly used to capture this information. The dysfunctional thought record (DTR) was initially developed (A. T. Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979) to assess the automatic thoughts of depressed patients; however, the DTR is generally useful in the assessment of automatic thoughts across a range of problems.

Several variants of the DTR have been developed. The original DTR (A. T. Beck et al., 1979) had several columns (see Figure 4.3). The first column is for noting date and time of the problematic situation. The second column is for a brief description of the situation, or if there was no external situation, the internal memory or experience that led to the negative automatic thoughts. The third column is for recording the emotional consequence of the automatic thought, which is not only named but also typically given a severity rating on a scale of 0 to 100. The final column is for listing the automatic thoughts and for rating believability on a scale of 0 to 100.