- •Isbn-10: 1-4338-0548-0

- •Introduction

- •Learning Theory: Classical Conditioning

- •Principles of Treatment

- •Role of Cognitive Variables in Classical Conditioning

- •Learning Theory: Instrumental Conditioning

- •Principles of Treatment

- •Role of Cognitive Variables in Instrumental Conditioning

- •Social Learning Theory: Self-Efficacy Theory

- •Principles of Treatment

- •Cognitive Appraisal Theory

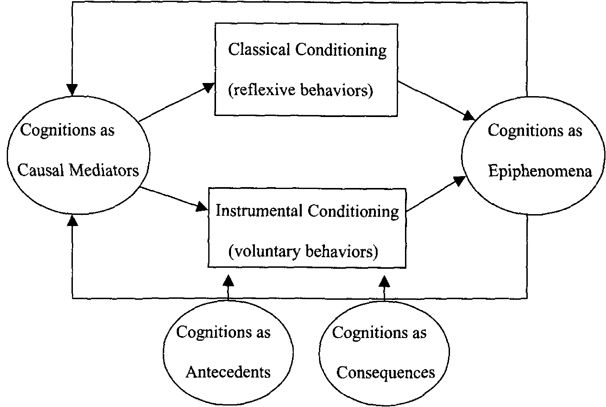

- •Figure 3.1

- •Table 3.1 Ellis’s Irrational Beliefs

- •Table 3.2 Common Cognitive Distortions

- •Cognitive Appraisal Theory and Expectancy–Learning Theory

- •Figure 3.2

- •Principles of Treatment

- •Cognitive–Behavioral Theory

- •Minimal Therapist Contact

- •Skill- and Reinforcement-Based Strategies Self-Monitoring

- •Relaxation

- •Behavioral Rehearsal of Social Skills and Assertiveness

- •Problem-Solving Training

- •Behavioral Activation

- •Behavioral Contracting

- •Habit Reversal

- •Exposure-Based Strategies Exposure Therapy

- •Response Prevention

- •Cognitive-Based Strategies

- •Rational–Emotive Behavior Therapy

- •Cognitive Therapy

- •Self-Instruction Training

- •Indications and Contraindications for Cognitive Strategies

- •Anxiety Disorder

- •Depression

- •Alcohol Abuse

- •Bulimia Nervosa

- •Mindfulness

- •Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- •Dialectical Behavior Therapy

- •Function Over Content

- •Incorporate advances in learning theory

Figure 3.2

Principles of Treatment

The primary assumption of cognitive therapy, whether in accordance with Ellis or Beck, is that dysfunctional thinking can be changed and, in turn, lead to symptomatic relief and improvement in functioning. Ellis noted that “Being constructivists (both innately and by social learning), and having language to help them, they are also able to think about their thinking, and even think about thinking about their thinking. Therefore, they can therapeutically choose to change their IBs [irrational beliefs] to more rational (self-helping) beliefs” (2003, p. 80).

A key concept is the development of alternative cognitive content that is more realistic and evidence-based and less governed by core irrational beliefs or schemas. Hence, the focus is on changing the content of beliefs, automatic thoughts, and assumptions. As Clark and colleagues (1999) note:

The degree of symptomatic improvement brought about by these interventions will depend on the extent of change produced in the information processing system. Moreover, recovery will be more enduring and relapse reduced if the underlying maladaptive meaning-structures, and not just negative thinking, are targeted for change during treatment. (p. 70)

Conscious reasoning is used to change in the content of beliefs. According to Beck and Clark (1997), “one of the most effective ways of deactivating the primal threat mode is to counter it with more elaborative, strategic processing of information resulting from the activation of the constructive, reflective modes of thinking” (p. 55). Cognitive therapy represents such elaborative, strategic processing. Thus, cognitive therapy functions at the conscious level to effect changes in the preconscious level.

However, the mechanism by which primal automatic thoughts are changed by more elaborative strategic thoughts is not well understood. Several models of change in cognition exist (Garratt, Ingram, Rand, & Sawalani, 2007). The accommodation model assumes that the content of underlying schemas is changed in profound ways. Another model, known as the activation-deactivation model, suggests that the schemas remain intact but become deactivated over the course of treatment. In a third model, schemas may remain unchanged, but new schemas develop as a result of therapy and these schemas incorporate skills for dealing with stressful situations (Garratt et al., 2007). However, the data on mechanisms are sparse (as described in more detail in a following section) and the precise mechanisms through which beliefs change remain unclear.

Another concept key to cognitive therapy is an empiricist approach. This involves incorporating more bottom-up processes rather than being predominantly driven by inferences or top-down processes that are guided by maladaptive schemas or illogical thinking. An empiricist approach also involves developing an awareness of one’s own thinking and learning to distance, or view one’s thoughts more objectively and to draw a distinction between “I believe” (an option that is open to disconfirmation) and “I know” (an irrefutable fact). Skills are taught not only for how to identify distortions in thinking but also how to categorize and distance from negative thoughts and how to develop more evidence-based and constructive thinking. Behavioral experimentation is used to gather evidence for the formation of more constructive thinking. These skills are then employed whenever negative emotions or dysfunctional behaviors are expressed. Hence, the skills provide a coping tool that is intended to remain in place and even strengthen after formal treatment is over. Cognitive therapy does not aim to teach accuracy in appraisals. Rather “the more relevant question is whether the person is able to conceptualize the situation in a manner that will facilitate mastery or coping” (Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999, p. 64). Learning to have flexibility in thinking and the ability to take multiple perspectives rather than a single narrow interpretation is a way of facilitating mastery and coping.

In sum, the fundamental process of cognitive therapy is to extract information from the environment that activates different ways of thinking. In Beck’s model in particular, this information is intended to compete with dysfunctional schemas or generate compensatory schemas that deactivate dysfunctional hypervalent schemas. The attainment of information occurs in a number of ways, including logical discussion of the evidence, disputation, and behavioral experimentation to gather evidence.