- •Velvet nel

- •Box 1.1. Case Study: Geotourism as a Strategy for Tourism Development in Honduras

- •Box 1.4. Experience: Business or Pleasure? Traveling as a Tourism Geographer

- •Box 2.1. Terminology: Tourism

- •Box 2.3. Case Study: Barbados's "Perfect Weather"

- •Box 2.3. (continued)

- •Income, investment, and economic development

- •Box 8.2. (continued)

- •Box 8.3. (continued)

- •Box 9.1. Case Study: Tourism and the Sami Reindeer Herd Migration

- •Box 9.3. Experience: Life around Tourism

Box 8.2. (continued)

Sources

Ashley, Caroline, Charlotte Boyd, and Harold Goodwin. “Pro-Poor Tourism: Putting Poverty at the Heart of the Tourism Agenda.” Natural Resource Perspectives 51 (2000): 1-6.

Ashley, Caroline, Dilys Roe, and Harold Goodwin. “Pro-Poor Strategies: Making Tourism Work for the Poor.” Pro-Poor Tourism Report 1 (2001).

Torres, Rebecca, and Janet Henshall Momsen. “Challenges and Potential for Linking Tourism and Agriculture to Achieve Pro-Poor Tourism Objectives.” Progress in Development Studies 4, no. 4 (2004): 294-318.

Although some existing economic activities might have the potential for linkages as the tourism industry becomes well established, at least initially the local economy may not be sufficiently or appropriately developed to support the tourism industry. Existing activities may require adaptations to meet the specific demands of tourism. The local agricultural industry may make a transition from a single crop (e.g., corn) to more diversified agriculture to supply the range of products in demand by the tourism industry (e.g., lettuce, tomatoes, jalapeno peppers). Likewise, the local fishing industry may need to expand in order to supply the quantity of products demanded by the tourism industry. Additionally, activities may need to be wholly developed; until then, products must be imported. However, to maximize the economic benefits of tourism, local linkages should be created as soon as it is feasible to minimize the dependence on external suppliers.

Economic Costs of Tourism

Places all across the globe would like to get a share of the trillion-dollar international and domestic tourism industry. Consequently, much emphasis is placed on the economic benefits of tourism. Yet, the potential for these benefits must be carefully considered to understand what the actual effect will be on a destination (i.e., who will receive the benefits and what will be the consequences). As such, we need to take a closer look at the nature of the jobs created in the tourism industry at a destination, the extent of economic effects, and the changes that occur in the local economy.

TOURISM EMPLOYMENT

The jobs created in the construction industry, the tourism industry, and the various supporting industries can attract immigrants from other regions of a country or other countries. This is particularly the case when tourism is developed in peripheral areas where there may not be a large enough local population to fill the new demand for labor.

However, this labor-induced migration may quickly outstrip available jobs and result in a labor surplus. In fact, areas with a high dependence on tourism may have higher levels of unemployment than surrounding regions. This is due to the number of people who move to the destination based on the promise of employment, or the hope of higher-paid employment than would be available to them in their home community.

In addition, tourism is both seasonal and cyclical, which has the potential to affect employment patterns. Even popular tropical destinations, such as the islands of the Caribbean, have a distinct tourist season. Higher rates of precipitation during the wet season, as well as the increased risk of hurricanes, are considered barriers to tourism (chapter 6). At the same time, the majority of tourists come from the Northern Hemisphere during the winter months for the inversion of cold to warm weather (chapter 2). Consequently, at these destinations, there is a high demand for labor during peak months, and tourism businesses may need to hire additional workers. Yet, during the low season, some of these workers may have to find temporary employment in other sectors or face unemployment.

Tourism employment is entirely based on the success of the industry. When a destination is experiencing growth, new jobs will be created in both tourism and related industries. For example, when a destination is developing or expanding, a tremendous amount of local and/or tourism infrastructure may be built, creating a boom in the construction industry. However, when the industry as a whole, or a specific destination, is experiencing a decline, jobs will quickly disappear. Moreover, tourism businesses may only provide services to tourists on an on-demand basis and will therefore require fewer full-time employees and fewer supplies.

One of the most common criticisms of the tourism industry is based on the type of jobs created. Many jobs are unskilled and low-wage, which can have few benefits for the local population. Tourism businesses may seek to minimize costs by providing services to tourists on an on-demand basis. Therefore, instead of a staff of full-time employees, businesses may rely on independent contractors who are paid an hourly wage or per job and who receive no benefits like health care or pension plans. For example, rather than maintaining a salaried staff of tour guides who are available to give regularly scheduled tours whether or not any tourists have signed up, a company is likely to hire guides for specific tours once they have filled. In addition, some of these contract jobs may be in the informal sector of the economy.

Many countries do not have minimum wage laws, do not enforce these laws, or generally have a low wage standard. Like other industries, multinational tourism companies take advantage of this. Tourism is an extremely competitive industry; there are many destinations around the world competing for investment from the same companies and visits by the same tourists. If the cost of wages at a destination reduces companies’ profit margins, they will choose to locate elsewhere. If it raises the cost of vacationing at that destination too much, tourists will choose to visit someplace less expensive. As such, to ensure that the destination continues to receive the income— particularly foreign income—from tourism, local or national governments may be reluctant to pressure companies for higher wages.

Highly paid managerial positions represent a smaller proportion of overall tourism jobs, and these positions may not go to local people. Particularly when tourism is developed in rural or peripheral regions of a country and/or less developed countries, the population may not have the necessary education, training, or experience to be able to hold these types of jobs. Additionally, multinational companies may prefer to import workers who are already familiar with company policies or who may be more likely to understand the needs of the targeted tourist market. Unless a concerted effort is made to develop the local resource base to be able to successfully hold higher-level tourism positions, a destination can become dependent on foreign expertise.

Finally, the growth of jobs in the tourism industry may have negative consequences in other areas of the economy. Jobs in the tourism industry may have higher wages than other local employment opportunities. They may be perceived to be less physically demanding than manual labor jobs or more stable than activities like agriculture that are highly dependent on unpredictable environmental conditions. As people choose tourism employment over others, this can contribute to labor shortages and declines in other parts of the local economy. Thus, tourism will not necessarily result in an increase in employment opportunities or produce a net gain in the local or national economy.

INCOME, INVESTMENT, AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

While tourism has the potential to support other economic activities, the reality is that tourism often grows at the expense of other activities around the destination. For example, land traditionally used for agriculture may be sold, voluntarily or under coercion, for commercial tourism development. Depending on the terms of the sale, this may present an opportunity cost for the farmer, as he or she exchanges the value of the land for the income that he or she would have derived from the annual produce of that land in the years to come. Furthermore, the potential for creating economic linkages between agriculture and tourism at the destination is diminished or lost altogether.

This can also lead to an overdependence on tourism as the principal source of income in a local or national economy. Rather than promoting economic diversification, this trend toward tourism growth at the expense of other economic activities can result in greater concentration in a single economic sector. As a result, the economy is more vulnerable to fluctuations in the industry, and tourism is a sensitive industry that may be adversely affected by any number of unforeseen factors that the destination has little or no control over.

Although foreign investment may initially provide an important source of income that allows for destination development, an overdependence on multinational companies can have a long-term impact on the nature of economic effects at the destination. The income these companies generate is more likely to be transferred out of the region or country instead of contributing to the multiplier effect. This is referred to as leakages. These are the part of tourism income that does not get reinvested in the local economy. Some leakage occurs with each round of spending after tourist dollars are introduced into the economy, until no further respending can take place. The direct effect will be mitigated if the tourism businesses are externally owned, because profits will be transferred out of the region or country. The indirect effects will be reduced if tourism businesses seek external suppliers for their products. Likewise, the induced effects will be eliminated if local people spend their earnings outside of the region or country or on imported goods.

The classic example of leakage is seen in the all-inclusive package mass tourism resorts. These large-scale chain resorts are owned by multinational companies based in the more developed countries of the world. When tourists travel from these same countries and spend their tourist dollars at the resort, those dollars may, in fact, be returning to the country of origin. Take, for example, the context of food. In some cases, despite the higher transportation costs of importing food, the company may be able to obtain food items at a lower cost from a subsidized mass producer at home as opposed to the higher per unit cost of a local producer. In other cases, local producers simply may not be able to sell their products to the resorts because they do not have the appropriate contacts, contracts, or the ability to provide buyers with receipts.8 Whether it is true or not, the perception exists that mass tourists don’t care where their food came from or that they will have concerns about the quality and integrity of local foods. They may suspect that this food was produced and/or processed under unhygienic conditions or that it will not be up to the same standards they are accustomed to at home. These types of resorts may also assume that mass tourists prefer the types of foods eaten at home and won’t try new types of foods for fear of getting sick.9

The result is that, although countries like Honduras, Mozambique, or Cambodia may have a positive travel account, they may not receive the full economic benefits of tourism. These less developed countries have little capacity to develop tourism on their own; therefore, they are likely to rely on multinational companies to do it for them. Even though they receive international tourists, there are typically high levels of leakages that reduce the multiplier effect. As a result, little money is retained or reinvested at the destination, and the goal of redistributing wealth between parts of the world remains unrealized.

Moreover, rather than redistributing a country’s wealth and economic opportunities, tourism may contribute to a further spatial concentration. This may be in an area that already has a stronger development base, such as a major metropolitan area, or it may be the development of a tourist zone. This can create or contribute to regional inequalities, as that area develops, modernizes, and experiences the economic benefits of tourism while other areas remain marginalized.

Likewise, tourism will not necessarily result in a redistribution of wealth among the population. Much of the money that is not leaked out of a region or country tends to stay in the hands of the upper- and middle-income groups. Despite concepts like pro-poor tourism (PPT) and the potential for tourism to improve the economic wellbeing of traditionally marginalized populations such as indigenous peoples, few of the economic benefits of tourism actually accrue to the poorest segments of a population. For the most part, tourism development does not incorporate poverty elimination objectives. This is because tourism is largely driven by the private sector and companies whose primary objective is profit.

In fact, tourism has the potential to further harm the local population, especially the poorest segments of that population. As a destination develops, it may experience increasing land costs and costs of living. Land is often assessed for tax purposes on its market value rather than its use. As land at an emerging destination is sold to tourism developers at a relatively high cost, the value of all of the land in the area may be reassessed, resulting in an increase in property taxes. This may make it increasingly difficult for landowners to be able to afford to live on and/or use their land as they had in the past. For example, a farmer may have a piece of land that has been in his family for generations. He would like to maintain this land for both the heritage it represents to him and its use as a working farm. However, his income from the farm may no longer be enough to support his family and pay the increased taxes to keep the land.

The value of goods and services may be adjusted based on the amount of money tourists will pay for such things as opposed to the local population. For example, property owners at a destination may have the opportunity to rent houses or apartments/ flats to tourists at a high per week price. As such, local residents might not be able to afford to rent living space within the destination area, and they will be forced to move elsewhere. Similarly, stores may cater to tourists who are able and/or willing to pay more for certain products. Again, residents might not be able to afford to buy these products, at least from these stores. Consequently, they may have to travel outside of the destination to obtain the products they need, and if this is not an option for them based on transportation constraints, they will have to find alternatives or go without.

Finally, a destination may experience a range of hidden economic costs associated with tourism. For example, there may be a financial cost associated with managing the social or environmental effects of tourism that will be discussed in the following chapters.

Factors in Economic Effects

In some cases, we will be able to clearly see the effects of tourism on the economy. This is most likely in communities or countries with relatively undeveloped or undiversified economies. For example, small island developing states (SIDS), whether they are located in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, or the Pacific, face similar constraints to economic development (e.g., limited resource bases, lack of economies of scale, reduced competitiveness of products due to high transportation costs, few opportunities for private sector investment, etc.).10 The development of tourism in the SIDS can result in clearly identifiable economic impacts, such as an influx of foreign investment, a decrease in the unemployment rate, and an increase in the per capita gross domestic product. In other cases, the impact of tourism on a country’s overall economy can be more difficult to determine. The development of tourism may reflect a redistribution of resources, such as an investment or employment in tourism instead of other economic activities.

The specific economic effects of tourism at a destination, and the extent of these effects, will likely vary widely. The often interrelated factors that may determine these effects can include the nature of the local economy and the level of development at the destination, as seen in the example above. Similarly, the type of tourism, ownership in the tourism industry, and tourist spending patterns at the destination can have an impact on these effects.

For example, mass tourism destinations are more likely to be characterized by large-scale multinational companies that may use foreign staff and rely on imported supplies. As such, leakages are going to be high. In contrast, niche tourism destinations are more likely to be characterized by small-scale, locally owned tourism businesses with significant local linkages and therefore a higher multiplier effect. However, many destinations have a combination of both, typically a higher proportion of small local businesses (e.g., hotels or restaurants), but the large companies will have the greatest capacity (e.g., the most beds or tables).

Organized mass tourists typically contribute the fewest tourist dollars to the local economy. One of the most prominent examples can be seen in the cruise industry. The large quantities of cruise tourists notoriously contribute very little to the local economy at the visited ports. Tourists may not venture farther than the markets at cruise terminals, which are often characterized by cheap, mass-produced, imported souvenirs like T-shirts. They may be reluctant to spend additional money on destination excursions when the majority of activities that take place onboard are included in the purchase price. Some never even leave the ship when it’s in port. In contrast, drifters and explorers, who spend longer at a single destination and rely less on the explicit tourism infrastructure, have greater opportunities to support local businesses.

Knowledge and Education

For the majority of tourists (actual and potential) around the world, money is one of the most important concerns. We may have a demand for tourism, but it is a nonessential expense. We have to determine how much of our disposable income we can devote to travel and what experiences we can afford. While this may be the only consideration for many tourists, there is a subset of socially conscious individuals who would be interested in supporting the local economy at the places they visit. However consumers may be faced with a choice: if they can’t afford a niche destination (one with a higher cost due to the lack of economies of scale but strong local linkages), do they accept a cheaper vacation at a mass destination (one with a lower cost due to economies of scale but higher levels of leakages) or stay home?

Even if tourists are interested in and willing to pay more for destinations that are economically beneficial to local people, they may not be knowledgeable enough to make an informed decision. In contrast to fair trade commodities, there is little in the way of widely known or recognized certification of tourism products. There are a few examples, such as Fair Trade in Tourism South Africa, which is considered to be the first program to certify that tourism enterprises have fair wages and working conditions and an equitable distribution of benefits.11 However, it often falls to individual tourism businesses to advertise their own policies on their website or other promotional literature, such as local ownership, fair wages, support of local farmers and craftspeople, and so on.

Tourism businesses must also weigh the higher cost of policies that support the local economy against the cost of not doing so. These are profit-oriented businesses, and paying higher wages or higher costs for locally produced supplies can reduce their

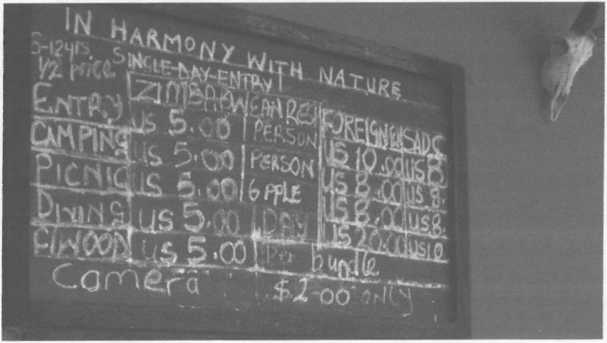

Box 8.3. Case Study: A Differentiated Price Structure at Tourism Attractions in Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe is an interesting case in tourism. The southern African country has a strong tourism resource base. Historically, wildlife has been the primary natural tourism resource, including the “Big Five” game animals that provide an attraction for safaris and hunting expeditions. This is complemented by other unique natural and cultural attractions, including four UNESCO World Heritage Sites (Great Zimbabwe, Khami Ruins, Mana Pools National Park, and Victoria Falls). From this base, tourism emerged as one of the country’s most significant economic activities, and Zimbabwe became one of the largest international tourism destinations in Africa. Today, however, the tourism industry faces numerous challenges.

Both domestic and international tourism have experienced significant declines. Zimbabwe has been in severe economic crisis since 2000. The country has experienced falling income levels and rampant inflation; both unemployment and poverty rates are as high as 80 percent. As a result, emigration, particularly among the educated middle and upper classes, and “capital flight”—where Zimbabweans with money have invested it outside of the country—have been a problem. Given these conditions, few Zimbabweans have the means to participate in tourism. Additionally, the country’s political turmoil led many countries to issue travel warnings recommending that their citizens avoid any nonessential travel to Zimbabwe. Other highly publicized issues, such as reports of human rights violations, high crime rates, high rates of HIV/AIDS infections, a cholera epidemic, and more, have all contributed to a generally poor international reputation that discourages international tourism.

The remaining vestiges of the country's tourism industry are characterized by a differentiated price structure. In other words, different categories of tourists are charged different rates for the same activities or services. Theoretically, this type of policy is argued to open up opportunities for local people to participate in tourism when they might not be able to otherwise. In particular, it is argued to have social benefits, where local people can appreciate their own natural or cultural heritage instead of reserving it for the exclusive use of foreigners. It is also argued that foreign tourists who are able to visit the country should be able to afford the higher rates and be willing to pay for the privilege of the experience. This income can be used to maintain the attraction and support the local economy. Moreover, higher fees for international tourists can be used to offset lower numbers of tourists received.

While this practice is not unique to Zimbabwe, the country provides an interesting case for examining its use. For example, admission at Zimbabwe’s most popular tourism attraction—Victoria Falls—is US$30 for foreign visitors and only US$7 for Zimbabwean residents. At Hwange National Park, the country’s largest game reserve, the difference is US$25 (US$30 for nonresidents versus US$5 for residents). However, even nominal admission fees can be beyond the means of much of the population and prevent them from visiting important national sites. At the same time, foreign tourists may come to resent being charged substantially higher fees on top of all of the other money spent on expected expenses like transportation, accommodation, food, activities, souvenirs, and more. This resentment can compound, considering that they have already found themselves subject to visa fees, airport taxes, and other costs not directly associated with tourism services. Faced with these costs, they may choose alternative destinations, such as game parks in neighboring Botswana. This is particularly applicable in the example of Victoria Falls. Shared with Zambia, the admission fee on that side of the border is only US$20 for foreign tourists.

The situation gets more complicated when foreign and domestic tourists travel together. For example, many upper- and middle-class Zimbabweans (and therefore the ones who are most likely to be able to participate in tourism) are educated abroad. They make friends and contacts with foreign nationals whom they may encourage to visit them when they return to their homeland. The differentiated price structure can make the hosts uncomfortable, as they have to ask their guests to pay more money. Beyond that, when tourism facilities or services are shared between residents and their guests, the locals may find themselves charged the foreign rate simply because they are traveling with a foreigner. Personal vehicle entry at a national park, for instance, is double for nonresidents of Zimbabwe (US$10 versus US$5 for residents). Accommodations can run as much as US$50 more per night for foreign tourists (e.g., the per night rate at a bed-and-breakfast located around Victoria Falls is US$120 for foreigners versus US$70 for residents). These concerns lead to the practice of borrowing Zimbabwean identification cards for their guests to ensure that everyone receives the local rate.

In theory, the concept of a differentiated price structure would appear to maximize the economic benefits of tourism—and to some extent, the social benefits. Domestic tourism is made available to an increasing number of residents who are able to appreciate and enjoy their national resources. While the per-tourist rate is lower, the higher numbers of tourists accounts for significant economic benefits. At the same time, international tourists are enabled to experience another country’s attractions. While their numbers are lower, the higher rates also account for significant economic benefits. As seen in this case, though, a differentiated price structure can have unintended effects diat are revealed on closer examination.

Discussion topic. Do you think domestic and foreign tourists should be charged different rates? Why or why not?

(continued.)

Figure

8.5. This sign shows the difference in tourist rates between

Zimbabwean residents and foreign visitors at Chinhoyi Caves, a

Category III National Park site. (Source: Velvet Nelson)