- •Velvet nel

- •Box 1.1. Case Study: Geotourism as a Strategy for Tourism Development in Honduras

- •Box 1.4. Experience: Business or Pleasure? Traveling as a Tourism Geographer

- •Box 2.1. Terminology: Tourism

- •Box 2.3. Case Study: Barbados's "Perfect Weather"

- •Box 2.3. (continued)

- •Income, investment, and economic development

- •Box 8.2. (continued)

- •Box 8.3. (continued)

- •Box 9.1. Case Study: Tourism and the Sami Reindeer Herd Migration

- •Box 9.3. Experience: Life around Tourism

Box 2.1. Terminology: Tourism

In chapter 1, we discussed the classic UNWTO definition of tourism. But because tourism can be approached from different perspectives, some additional terminology is useful. Inbound tourism is where tourists from somewhere else, typically another country, are traveling to that destination. Outbound tourism is where tourists are traveling from a place to a destination, again typically in another country. This marks a distinction between domestic tourism, which includes those tourists traveling within their own country, and international tourism, which includes those tourists traveling to another country. Additional distinctions may be made between short-haul tourism and long-haul tourism. This is based on either distance or travel time by a particular mode, or type, of transport. For example, a short-haul flight is generally considered to be less than three hours, while a long-haul flight is longer than six. However, there is no standardized measure for how these categories are actually defined.

Discussion topic. Do you think short-haul tourism can be international tourism and long- haul tourism domestic tourism? Why or why not?

The Demand Side

One approach to tourism is from the demand side, with a focus on tourists. This is, of course, a fundamental component of tourism: tourism would not exist without tourists and the demand for tourism experiences. Interestingly, however, the demand side has often been a less studied component in the geography of tourism. Instead, this approach has been seen as a topic more in the realm of psychology, sociology, or anthropology. Yet, the demand side nonetheless has distinct implications for our understanding of geographic patterns in tourism. The first half of this chapter introduces some of the theories and concepts that have been put forth to help us understand tourism from the demand side.

TOURISM

In

the last chapter, we began to consider the different ways we think of

tourism. When we think about our experiences, we are thinking about

the demand side of tourism. Therefore, one of the easiest ways for us

to conceptualize tourism is as a process with a series of stages

(figure 2.1).

In

the last chapter, we began to consider the different ways we think of

tourism. When we think about our experiences, we are thinking about

the demand side of tourism. Therefore, one of the easiest ways for us

to conceptualize tourism is as a process with a series of stages

(figure 2.1).

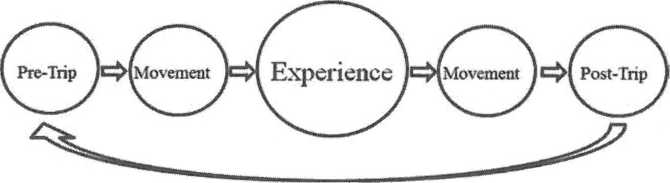

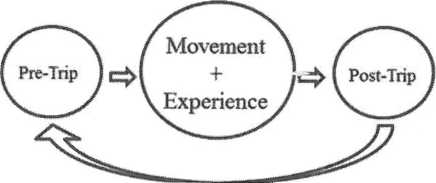

Figure

2.1. This conceptualization approaches tourism from the demand side

and takes into consideration the stages that contribute to the

overall process of tourism. These stages do not necessarily occur in

a linear fashion but may overlap and influence the others.

This process begins in the pre-trip stage, when we think about traveling and consider our options. We might evaluate different destinations in terms of the resources and attractions of each place, the tourism products (i.e., the type of experiences) offered there, and the level of infrastructure (e.g., accommodations or transport accessibility), and how they match up with our interests and expectations. Likewise, we will consider the overall cost of a trip to these places in relation to our budget. We have access to a tremendous amount of information to aid us in this evaluation and decision-making process. We rely on our previous experiences, input from family and friends, and the ideas and images of destinations that come from a range of media sources (e.g., news, movies, popular television shows, travel-related television shows, tourism guidebooks, travel magazines, and destination promotional literature). In particular, the Internet has become the most important source of tourism information in today’s society. This includes travel booking sites like Expedia or Travelocity, review sites like TripAdvi- sor, destination-specific websites, and a host of professional and personal travel blogs. In general, the Internet has made this stage easier—at least in the parts of the world with widespread Internet access—in that almost all aspects of pre-trip planning may be completed online.

The next three stages comprise the trip itself. For many trips, these stages will occur one after the other. In the movement stage, we use some form of transportation to reach the place of destination. At the destination, the experience stage is the main component in the process, in which we participate in a variety of activities. Then we repeat the movement stage as we return home again. For example, the Midwestern family taking a trip to Disneyworld may fly from their nearest airport to Orlando, Florida (movement), spend a few days at the resort and/or theme parks (experience), and then fly home (movement). In this case, movement is simply a means to an end to get to the destination and the experience stage. However, these stages are not always distinct, and the act of traveling can be an integral part of the experience stage. For example, the Midwestern family on a road trip may take a scenic route and visit any number of attractions over the course of the trip. In this case, the movement stage lasts the duration of the trip, from the time they leave home to the time they return. The experience stage takes place concurrently with the movement stage.

The final stage is the post-trip stage, which occurs after we return from our trip. We relive our trip through memories and conversations about the trip, as well as through tangible products of the trip, like pictures and souvenirs. These memories can be positive or negative, depending on what happened during the three principal stages of the trip. This stage is typically most intense in the period immediately following the trip, and although it diminishes over time, memories can be triggered by many things for a long time afterward. The tourism process then becomes circular, when we tap into these memories and past experiences to help us make decisions when we start planning our next trip (i.e., the pre-trip stage).

One of the principal advantages of this demand side conceptualization of tourism is that it is readily understood and doesn’t complicate something that should be relatively straightforward. In addition, it takes into consideration the role of pre-trip planning and the decision-making process, which are neglected in typical definitions of tourism that focus only on travel to a destination and activities undertaken there.

TOURISTS

Based on the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) definition of tourism quoted in chapter 1, a tourist could be defined as a person who travels to and stays in a place outside of his or her usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business, or other purposes. While this official-sounding definition is often used to identify tourists for the purpose of record keeping and statistics, it holds relatively little practical meaning to help us conceptualize who tourists are, as it is broad enough to encompass anything from children on vacation with their parents to adults traveling for work, and from week-long spring break partiers to students spending a semester studying abroad. Instead, it is popular ideas and stereotypes that have long been more influential in shaping our ideas about tourists.

The term tourist came into widespread use in the nineteenth century, and even then there were clear—and not always flattering—connotations. Up to this time, explorers were recognized to be individuals who traveled to places that had not previously been extensively visited or documented by others from their society. Likewise, travelers were considered to be those who traveled for a specific purpose, such as business enterprises or official government functions. The new category of “tourists,” however, was different from either of these. Unlike travelers, tourists were regarded as individuals who did not travel for any purpose other than the experience of travel itself and the pleasure they derived from that experience. Unlike explorers, tourists were often criticized for traveling to the same places and having the same experiences as all of the explorers, travelers, and even other tourists who came before them.

From this time, highly satirized representations of tourists began to appear in various media, from newspapers to novels. Today, these ideas are more widespread— and more exaggerated—than ever. Take, for example, the opening scene of the 2010 family-friendly animated comedy Despicable Me, in which the unruly child of the loud, overweight, brightly dressed, camera-wielding American tourists accidentally exposes the villainous theft of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It is this well-known concept of tourists as a category of people that provokes the sort of reaction expressed in the hilarious Uncyclopedia entry titled “Tourist—The Stereotype”: “Tourists. We all have ’em. They infest every corner of the globe. Korea, with admirable common sense, arrests all tourists at the border and nukes ’em. . . . Most other nations on Earth, sadly, tolerate them.”1

Although it has long been easy to make fun of tourists based on stereotypes, it is far more difficult to make generalizations about tourists in reality. Of course, there are always tourists who continue to fuel the stereotypes. Yet, there are also those who may be closer in spirit to the early explorers or have motivations in common with travelers (as even the official UNWTO definition explicitly includes business as well as other purposes). To accommodate the differences that exist between tourists, scholars have developed tourist typologies to identify categories (or types) of tourists. Typologies have used many different variables to categorize tourists, such as motivations and behavior as well as demographic characteristics, lifestyle, personality, and more. This type of framework is typically conceptualized as a spectrum or continuum of tourists, in which several important categories are identified and defined. These categories merely identify some of the characteristics of tourists at certain points on the continuum. Not all tourists can be grouped into these defined categories but instead will fall at various points along the continuum between categories.

While many different typologies have been proposed, the following simplified framework is often used as a summary of key categories from the most influential typologies. To some extent, this framework is similar to the earlier distinctions made between explorers, travelers, and tourists; it divides tourists into four broad types based on factors such as the purpose of travel and the type of experience sought.2

The drifter occupies one end of the spectrum. Drifters are tourists who likely do not consider themselves tourists. Like explorers from an earlier era, this category of tourist may be characterized as a pioneer who is the first to “discover” new and developing destinations. They seek out these destinations in an effort to avoid other tourists. Such places may have little in the way of a dedicated tourism infrastructure or tourism services. As a result, these tourists may stay in local guesthouses or private homes, use local transportation, shop at local markets, and eat at local restaurants and kitchens. Whether it is out of interest—or necessity, given the nature of these destinations—drifters immerse themselves in the local culture. For some, this is a process of education and self-exploration. For others, it is about doing something different, something not usually done.

The explorer bears resemblance to the earlier definition of a traveler. This category of tourist may have motivations for travel other than simply diversion, whether education, religious enlightenment, mental or physical well-being, or other specific types of experiences at the destination. These tourists look for unusual types of experiences and greater contact with the local population than just interacting with the people who hold service positions in the tourism industry, such as front desk clerks, restaurant servers, or housekeeping and maintenance staff. Explorers typically make their own travel arrangements and rely on a combination of both the tourism infrastructure and the local infrastructure. For example, these tourists may arrive at the destination by the same means as other categories of tourists, but instead of taking a tour bus or hiring a private taxi to explore the destination, they may take the local bus (figure 2.2).

In this typology, the traditional “tourist” category is divided into two different types. The next type along the continuum is the individual mass tourist. For these tourists, the primary motivation is typically some form of relaxation, recreation, or diversion, and they have some desire for things that are familiar and comfortable. They are generally dependent on the tourism infrastructure for getting to and staying at the destination, and they may use tourism industry services for at least part of their trip, such as taking a guided tour at the destination. However, these tourists are also interested in having experiences at the destination that would not be available to them in their home environment, and they will seek the opportunity to explore the destination, albeit in a relatively safe manner.

Finally, the organized mass tourist occupies the position at the opposite end of the continuum. These tourists are primarily interested in diversion and escaping the boredom or repetition of daily life. They place a high emphasis on rest and relaxation and enjoying themselves with good food and/or entertainment. These tourists are less

Figure

2.2. This "explorer" is waiting for Bus Eireann in Trim,

Ireland. Although Trim Castle can be visited on guided traveling

tours and day trips, he preferred utilizing the public

transportation infrastructure and having the freedom to choose his

experiences instead of a pre-packaged alternative. (Source: Carolyn

Nelson)

interested in unique experiences of place and are more likely to travel to destinations that are familiar or have characteristics that are familiar. Therefore, even if they travel to a foreign destination, they will stay in recognized brand name (i.e., multinational) resorts. These facilities are designed to provide the standard of accommodation, services, or types of food that such tourists are accustomed to at home. Organized mass tourists are highly dependent on the tourism infrastructure and services to structure their vacation. This may be a package that bundles services together at competitive prices, whether it is a comprehensive guided tour (with all transportation, accommodation, most meals, and tour services included) or a resort package (accommodation, some or all meals, and airport transfers included). As a result, little additional planning for the trip is necessary, there is little uncertainty about what will happen on the trip, and there may be little incentive to stray from the confines of the tour bus or resort complex. Thus, there is little to no interaction with the people or the place of the destination.

Box 2.2. In-Depth: Place-Specific Tourist Typologies

Although tourist typologies have primarily come out of tourism studies based in fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology, these frameworks have utility for the geography of tourism as well. Many early tourist typologies sought to explore general categories of tourists that could be applied across different types of destinations for the purpose of better understanding tourists and tourism. However, more recent typologies have recognized that these general typologies are often not particularly useful in efforts to understand tourism as a place-based phenomenon. As a result, studies in the geography of tourism have developed place-specific typologies that ate geographically bound to a particular destination to provide a better understanding of its specific circumstances. This will allow tourism stakeholders (i.e., the various individuals or organizations that have an interest, or stake, in tourism) to better plan, manage, and market tourism at that destination.

In one example, a place-specific tourist typology developed for Cancun, Mexico, took data provided by actual tourists from visitor surveys and interviews to identify categories of tourists and to discuss the characteristics of these tourists. Tourism stakeholders can use the resulting typology to understand how the services and experiences provided at that destination match the expectations and desires of tourists and, perhaps more importantly, how it can be improved. The Cancun typology follows the model established by the generalized typology—although, given the nature of this destination, tourists were concentrated at the mass tourist end of the spectrum (table 2.1).

For example, the “Euro Off-Beat” tourist category characterized the explorer/independent mass tourist end of the continuum. This category describes European tourists in their late twenties to early forties who stay at the destination for a week or longer and are interested in experiencing the region’s historical and cultural attractions. As is typical of this type of tourist, they are likely to stay in the destination’s principal resorts, but they also seek to explore the destination beyond the resort. Consequently, they typically do not use all-inclusive packages but take tours and eat at restaurants outside of the hotel. In general, these tourists find it difficult to have the type of experience they desire, and the data indicate that, given current conditions, they would be unlikely to return.

In contrast, the “Sun, Sea, and Sand Family” tourist category occupies a position at the organized mass tourist end of the continuum. This category describes predominantly American families looking for a good value vacation of a week or less. They may have some interest in visiting popular tourist attractions in the region, such as the archaeological ruins at СЫсЬёп Itza, but they will typically spend most of their time at the beach or pool, participating in resort activities, and eating at on-site restaurants. These family tourists don’t like the party atmosphere that attracts the “Spring Breaker” tourists, and they consider this a detraction for the destination. However, these tourists appreciate the range of discount packages offered by the destination that gives them the opportunity to take their families on a beach vacation.

Discussion topic. What could the destination do to better meet the expectations and demands of the Euro Off-Beat tourists? Of the Sun, Sea, and Sand Family tourists?

Tourism on the web\ Cancun Convention and Visitor Bureau, “Cancun Travel,” at http: //cancun. travel/en /

(,continued)

Box 2.2. (continued)

Table 2.1. Summary of Characteristics for Each of the Categories of Tourists Identified in Cancun's Place-Specific Typology (Categories derived from data provided by tourists at the destination.)

Type of Tourist Key Characteristics

"Euro Off-Beat" Tourist

"Sun, Sea, and Sand Family" Tourist

"Business Breaker" Tourist

"Non-Breaker Student" Tourist

Late 20s to early 40s European, not American Not “all-inclusive" tour Longer stay

Visits off-beat, historical, archaeological, and "Mundo Maya" sites Older—early 40s to late 60s Family vacation

Mostly interested in "sun and sand"

Strong interest in good service and good food

May visit a mass tourism archaeology site

Late 20s to late 30s

Nonfamily vacation

Not "all-inclusive" tour

High expenditures

Brief stay

Mostly interested in "sun and sand"

Not interested in visiting archaeological, historical, or “Mundo Maya" sites Early 20s

Likely to be American

Organized student package tour, but not classic "Spring Breaker"

Visits off-beat, archaeological, and historical sites

Source

Torres, Rebecca Maria, and Velvet Nelson. “Identifying Types of Tourists for Better Planning and Development: A Case Study of Nuanced Market Segmentation in Cancun.” Applied Research in Economic Development 5, no. 3 (2008): 12—24.

TOURIST MOTIVATIONS

Clearly these types of tourists have different motivations for and interests in tourism experiences. In the geography of tourism, we need to know what factors cause people to temporarily leave one place for another. If we understand these factors, we can begin to explain why certain places developed as significant tourist-generating regions and why others became significant receiving regions. Likewise, it helps destinations to better know where their potential tourist markets are by matching up what they

have to offer with the places where the demand for that product is greatest. However, motivations may be complicated, and it is rarely just one thing that causes people to seek tourism experiences.

The motivation that has long been most commonly associated with tourism is the pursuit of pleasure. However, implicit in this motivation is the real or perceived need for a temporary change of setting. This may be considered a geographic push factor, or something that impels people to temporarily leave home to travel somewhere else. We may think of this as an escape from the routine of daily life with the associated home and work issues, or boredom with familiar physical and social environments. Correspondingly, it is assumed that there is something that can be obtained at the destination that cannot be obtained at home. This may be considered a geographic pull factor, or something that attracts people to a particular destination. The pull may be something tangible that may be obtained at the destination, like being able to buy certain types of local products or eat authentic local cuisine. In most cases, however, it is an intangible, like having the opportunity to interact with new people, getting a week’s worth of sunny 80°F weather in the middle of winter, or having access to fresh snow at a prime ski resort. For both the push and the pull, this “something” will be different for everyone.

Borrowing from one of geography’s related disciplines—anthropology—we can see how these motivations have been laid out in Nelson Graburn’s concept of tourist inversions.3 In this theory, the experience we seek in our temporary escape is one of contrasts. Much of this involves a shift in attitudes or patterns of behavior away from the norm to a temporary opposite. One of the most common examples is the inversion from work and stress to peace and relaxation. For example, when we spend a long period of time working hard at school or at a job (or, in some cases, both simultaneously), tourism becomes our means of seeking the opposite: going on vacation for a period of rest and relaxation away from the stresses of what occupies us in our daily lives. Likewise, the shift from economy to extravagance is another common inversion that applies to many of us. We often have to budget our money in the course of our daily lives, but we will save up and splurge on a vacation. During these few days, we may spend more on food, drinks, entertainment, and other activities than we normally would.

In some cases, these inversions in behavior contribute to the generally poor reputation of tourists in many parts of the world. In particular, many inversions go from moderation to excess. Graburn suggests that overindulgence in food is the product of one tourist inversion. The same idea applies to overindulgence in alcohol and drugs. This inversion, as highlighted by MTV, is the one that gives spring break tourists— and, by extension, spring break destinations—a bad name. In the case of this inversion, students who usually go to class, study, work, party occasionally, and generally live within the norms of society travel to a spring break hotspot during the designated semester break and party to excess, with all that it entails.

There is also a geographic dimension to tourist inversions, in terms of a shift away from the tourist’s home and community toward a temporary opposite. This shift is much more locally contingent, and the inversions may, in fact, work both ways. One of the most common inversions of this type involves the movement from cold climates to warm ones. People in middle and upper latitudes that experience long, cold winters may seek to escape that weather—and the associated symptoms of seasonal affective disorder—for a short time by traveling to a warm, sunny place in the lower latitudes (figures 2.3 and 2.4). At the same time, people in warm climates may travel to colder ones to be able to participate in winter sports, such as skiing. People in densely populated urban areas may seek to escape the congestion, noise, and pollution of the city for expansive natural areas such as the national parks, although people living in rural areas or small towns may seek to get away from the insularity of that life by getting lost in a big city.

TYPES OF DEMAND

In the last chapter, our definition of demand included both those persons who travel and those who wish to travel. Consequently, we need to distinguish between different types of demand, including effective demand, suppressed demand, or no demand. Effective demand is the type of demand we typically think of, as it refers to those people who wish to and have the opportunity to travel. We can measure effective demand relatively easily with tourism statistics like visitation rates and participation in certain tourism activities.

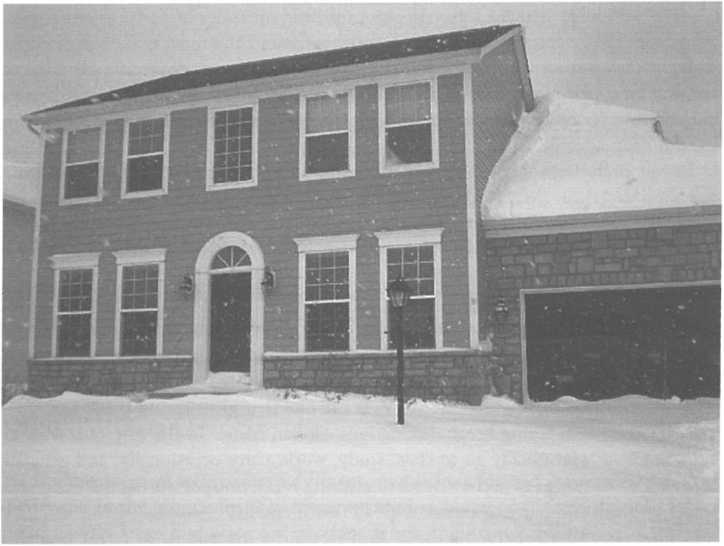

Figure

2.3. For many people who live in cold-weather climates, long

winters of dealing with icy and snowy conditions, such as these

occurring in the U.S. state of Ohio, can be a distinct geographic

push factor for tourism. (Source: Amber Fisher)

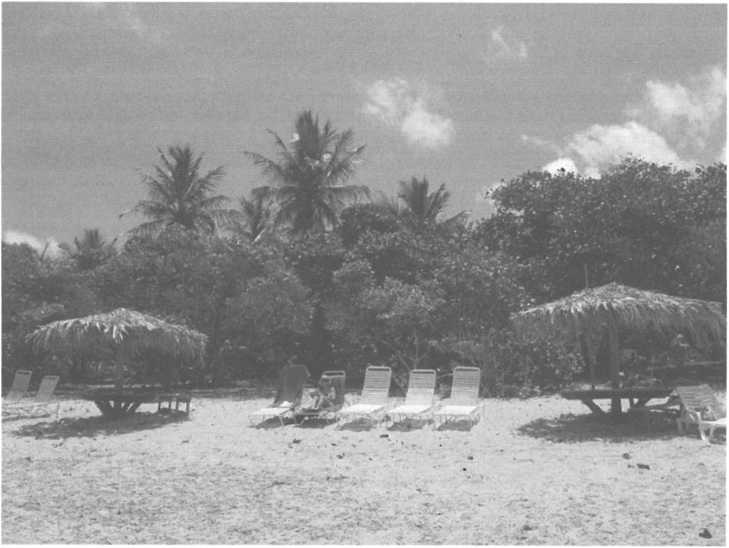

Figure

2.4. Just as a cold-weather climate can serve as a push factor,

warm and sunny climates, such as that found on the Caribbean Island

of Tortola, British Virgin Islands, can serve as a distinct

geographic pull factor and create a demand for the winter/spring

break. (Source: Tom Nelson)

However, this does not give us a complete picture, as participation is not always reflective of desire. How many of us have wanted to travel (i.e., have had a demand for travel) at some point in our lives but have not been able to, for one reason or another? Suppressed demand refers to the people who wish to travel but do not. It is much more difficult to measure the number of people who simply want to travel. Moreover, there are many reasons why people who wish to travel do not, so we can break this category down even further. Potential demand is a type of suppressed demand that refers to those people who want to travel and will do so when their circumstances change. For example, students often have a potential demand for tourism. This means that they may have an interest in (or a perceived need for!) tourism experiences, but they may not have the discretionary income (i.e., the money that is left over after taxes and all other necessary expenses of life like rent, food, transportation, clothing, tuition, and books have been taken care of) to travel.

Deferred demand is a type of suppressed demand that refers to those people who want to travel but have to put off their trip, not because of their own circumstances but because of some problem or barrier in the supply environment. This could be a problem—or even a perceived problem—at the desired destination. For example, after the April 2010 explosion on the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig and the subsequent oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, there was much speculation about the number of tourists who would cancel their summer vacations to the many Gulf Coast destinations due to