- •Velvet nel

- •Box 1.1. Case Study: Geotourism as a Strategy for Tourism Development in Honduras

- •Box 1.4. Experience: Business or Pleasure? Traveling as a Tourism Geographer

- •Box 2.1. Terminology: Tourism

- •Box 2.3. Case Study: Barbados's "Perfect Weather"

- •Box 2.3. (continued)

- •Income, investment, and economic development

- •Box 8.2. (continued)

- •Box 8.3. (continued)

- •Box 9.1. Case Study: Tourism and the Sami Reindeer Herd Migration

- •Box 9.3. Experience: Life around Tourism

Box 1.1. Case Study: Geotourism as a Strategy for Tourism Development in Honduras

The incredible growth of the global tourism industry has been accompanied by the development of increasingly specialized tourism products to meet demands for ever more specific tourism experiences. Geotourism is one such product based on the intersection of geography and tourism. As defined by the National Geographic Society (NGS), geotourism is “tourism that sustains or enhances the geographical character of a place—its environment, culture, aesthetics, heritage, and the well-being of its residents.”1 As such, geotourism should highlight and enhance the human and physical characteristics of a place that make it unique. Likewise, it should be economically profitable, to contribute to the conservation of those characteristics.

In 2004, the government of Honduras announced that it would become the first nation in the world to sign the National Geographic Geotourism Charter and make geotourism its official tourism strategy. Honduras is a Central American nation that has struggled with crime and corruption, chronic unemployment, endemic poverty, high rates of emigration, and devastating natural hazards. Consequently, it has remained one of the least developed countries in the region. Based on the successful examples of other countries in the region such as Costa Rica and Belize, Honduras sought to develop tourism to create jobs, increase foreign exchange, diversify its economy, and alleviate poverty. Yet, Honduras had been unable to pinpoint a strategy to effectively and appropriately develop its tourism potential, until the discovery of geotourism.

Honduran Minister of Tourism Thierry de Pierrefeu stated that the country was “ideal” for the implementation of the then newly developed geotourism concept. Honduras has a diverse set of resources for tourism, including white sand beaches and coral reefs, mountain topography, tropical rain forest vegetation, national parks and biosphere reserves, pre-Columbian architectural ruins, Spanish colonial history, and indigenous cultures, among others. Moreover, like other countries with similar circumstances, Honduras would like to maintain these resources, raise awareness about the authenticity of such place-based characteristics among international audiences, and strengthen national identity and pride among its own citizens.

Despite the National Geographic framework, geotourism development in Honduras has been slow. One of the first steps in developing and implementing this strategy included creating a geotourism map guide to the country’s primary tourist region along the Caribbean coast to highlight and protect key tourism resources. At the same time, NGS and the Honduras Institute of Tourism looked to establish a center to attract tourists who would be interested in the experience Honduras has to offer and support the tenets of geotourism. Yet, problems with political instability and social unrest continue to be key barriers to the development of tourism. In particular, many countries imposed travel alerts for Honduras after a governmental coup took place in 2009. Although these alerts have since been lifted, perceptions of insecurity can linger for years.

Honduras was only the first destination to take the initiative in developing geotourism. Since 2004, other destinations such as Guatemala, Norway, Romania, and the U.S. states of Arizona and Rhode Island have signed on to become geotourism destinations and emphasize the character of place.

Discussion topic: If geotourism is intended to highlight the unique geographic character of a place, do you think all tourism might be considered geotourism? Why or why not?

Tourism on the web-. Honduras Institute of Tourism, “Honduras: The Central America you know—the country you’ll love,” at http://www.letsgohonduras.com

Note

1. National Geographic Society, “The Geotourism Charter,” accessed February 1, 2011, http://travel .nationalgeographic.com/travel/sustainable/pdf/ geotourism_charter_template.pdf, 1.

Source

Burnford, Angela. “Honduras, National Geographic Announce ‘Geotourism’ Partnership.” National Geographic News, October 24, 2004. Accessed February 1, 2011. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/ news/2004/10/1025_041025__travelwatch.html.

such as the tropical rain forest climate and biome in places like Hawaii, Costa Rica, or Thailand. Recognizing the attractiveness of such destinations, countries possessing these environments have a clear incentive to protect these forests as parks and preserves instead of developing them in more environmentally destructive ways. Yet, as more and more tourists come to visit the park, the overcrowding overwhelms the infrastructure, paths are degraded, natural features are vandalized, waste builds up, and so on.

What Is the Place of “the Geography of Tourism” in Geography?

As we recognize that travel has long been a part of geography and that tourism is an inherently geographic activity, “the geography of tourism” should seem less and less improbable. In recent years, the field has seen considerable growth. Major academic geographic associations now have special groups or commissions devoted to the topic, including the Recreation, Tourism and Sport specialty group of the Association of American Geographers (AAG), the Geography of Leisure and Tourism research group of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), and the Commission on the Geography of Tourism, Leisure, and Global Change of the International Geographical Union (IGU). Research on topics in the field is published in journals across both geography and tourism studies, including the dedicated journal Tourism Geographies. Yet, the place of the geography of tourism within the field of geography is still not widely understood and could use some further discussion. In particular, if we return to our introduction of geography, we see that we can approach the subject regionally or topically.

TOURISM AND REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY

The concept of regions has long been considered an effective means of organizing and communicating spatial information, especially to nongeographers. As such, regions are applied in the context of tourism in a number of ways, not the least of which is the study of tourism generally and the geography of tourism specifically. Many tourism geography textbooks use a regional approach to examine circumstances of tourism in different parts of the world.

Taken a step farther, the concept of regions may be used to explain patterns or trends in tourism. For example, tourist-generating regions are source areas for tourists, or where the largest numbers of tourists are coming from. We can identify characteristics of these regions that stimulate demand for tourism, such as an unfavorable climate or a high level of economic development. Likewise, we can identify characteristics of regions that would facilitate demand, such as a good relative location and a high level of accessibility. Tourist-generating regions are important in helping us understand why certain people may be more likely to travel and where. Theoretically, this information may be used to create new opportunities for people to travel. Specifically, if we understand the barriers to travel for a particular region, we can begin to develop strategies to overcome these barriers. In practical terms, tourism marketers use this information. If a destination identifies its largest potential tourist market, then it will be able to develop a promotional campaign targeted at that audience.

Conversely, tourist-receiving regions are destination areas for tourists, or where the largest numbers of tourists are going. We can identify characteristics of these regions that contribute to the supply of tourism. Again, a good relative location and a high level of accessibility are important, as well as the attractions of the region and a well-developed tourism infrastructure. Tourist-receiving regions are important in helping us understand why certain places have successfully developed as destinations. This information may be used as an example for other places also seeking to develop tourism.

International agencies such as the UNWTO use regions to examine trends in the global tourism industry. The UNWTO identifies Europe as both the single largest tourist-generating region and the largest receiving region. As of 2009, the European region accounted for 55 percent of international tourists and 52 percent of international tourist arrivals. This is attributed to a range of factors, including a diverse set of attractive destinations, high levels of accessibility, a well-developed tourism infrastructure, and a long tradition of travel. Yet, long-standing trends in international tourism have been changing in recent years. The importance of Europe as both a generating and a receiving region has been declining with the emergence of new tourists and new destinations. Although the economic troubles of 2009 contributed to a 4 percent decline in international tourist arrivals, the UNWTO reported that Europe posted one of the largest rates of decline among receiving regions.9

Finally, destinations use regions to present information to potential tourists. In some cases, a national destination will use the concept to organize smaller destination regions. This allows tourists searching for a destination to match their interests or requirements to a particular place within that country. For example, the Canadian Tourism Commission (CTC), establishes five distinct regions based on different resources and experiences: Atlantic Canada, Canada’s North, Central Canada, Mountains West, and the Prairies. In other cases, several nations will work together to generate interest in and awareness of themselves as a destination region. For instance, the Caribbean

Tourism Organization (CTO) is made up of thirty-five members in the greater Caribbean basin, and the organization’s stated purpose is “to increase significantly the inclusion of the Caribbean region in the set of destinations being considered by travelers.”10

The regional approach to the geography of tourism is particularly useful for examining cases of tourism within different regional contexts. Moreover, there are distinct applications for critical regional geography in research on the geography of tourism. In particular, this research examines regional concepts and meanings and the implications this has for the development of tourism (see box 1.2). However, this approach is limited in its potential to fundamentally unpack the concept of tourism. Instead, we will be using a topical approach throughout this textbook.

TOURISM AND TOPICAL GEOGRAPHY

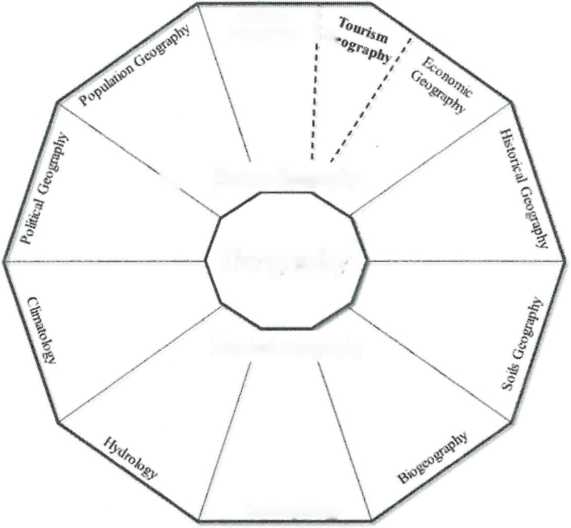

If we return to the graphic depiction of geography in figure 1.1, we can see how topical branches fit together to comprise the subdivisions of human geography and physical geography, as well as geography as a whole. Yet, fitting the geography of tourism into this picture is no easy task. If pressed, most geographers would probably consider the geography of tourism to be a branch of human geography. Certainly tourism is a human phenomenon, and much of the focus in the geography of tourism is on human ideas and activities. Likewise, the majority of geographers who study the geography of tourism are, in fact, human geographers. This would suggest that we could insert a new “wedge” into the pie for tourism geography, and it would largely go unquestioned (figure 1.3).

This kind of conceptualization may be useful in showing that the geography of tourism is a topical branch that coexists with the others at the center of geography. However, it is less useful in helping us understand how to approach its study. As a new space for the geography of tourism is created, it may be tempting to come to the conclusion that the topic can stand alone. To some extent, overlap exists between the topical branches. Yet, this goes beyond mere overlap in the case of the geography of tourism. All of these other areas—cultural geography, economic geography, population geography, political geography, etc.—have much to contribute to the study of tourism through the lens of geography. Moreover, by tracing the geography of tourism through the human side, we lose some of the components in physical geography— geomorphology, climatology, hazards, etc.—that also play extraordinarily crucial roles in shaping tourism destinations and activities. Furthermore, we cannot truly separate the human and physical divisions, as much of tourism involves interactions between people and the environments of the places they visit.

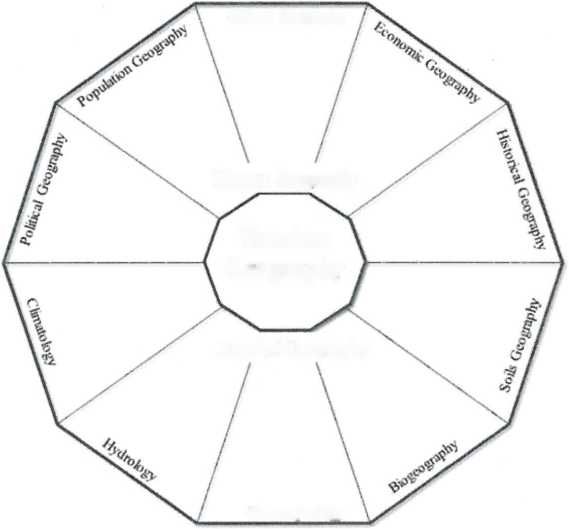

Rather than thinking of the geography of tourism as part of this hierarchy of topics, it may be more productive for our purposes to think of the geography of tourism in the same way geography as a whole is conceptualized. With the geography of tourism in the center of the schematic, we can recognize that there are both human and physical components at work in tourism, and each of the topical branches can help us understand a different part of the complex phenomenon that is tourism (figure 1.4).

Box 1.2. In-Depth: A Critical Regional Geography of Tourism

The concept of regions has a very long tradition in geography. Throughout the classical era, regions were used to divide the world into units in which geographers could describe the physical and human characteristics of these areas. However, geography in the contemporary era moved away from this description of places to focus on explanations of geographic patterns. This shift in emphasis caused many geographers to question the role of regions in the modern study of geography. Some felt that regions were an outdated concept that had outlived its usefulness in the field. But others argued that regions still undeniably have a part to play in the world today, and, as geographers, it is our responsibility to try to understand the world. As a result, these geographers adapted the concept of regional geography to provide die means of understanding how people continue to view the world through regions. This critical regional geography is based on the idea that regions are “social constructions,” which means that regions do not just exist in the world—people define them, create boundaries for them, and give them meanings. In addition, they are constandy evolving with the world as new events occur and new ideas are created.

In tourism, regions are frequently used to organize patterns and destinations. The UNWTO organizes data and activities based on broad regional categories (e.g., Europe, Asia and the Pacific, the Americas, the Middle East, and Africa). Similarly, popular tourism guidebooks geographically group destinations (e.g., Europe, Central America, East Africa, or the South Pacific). At the most basic level, these categories provide “containers” for information; in other words, they make it easier for people to find and process information for a particular area. Yet, these categories are also associated with meanings. Although it’s probably unconsciously done, we mentally organize the world by regions, so we mentally locate a destination by the region we associate it with. This means that what we think about that region shapes what we think about that destination. In the geography of tourism, then, we might critically evaluate regional concepts to understand how these ideas might affect the development of a place as a tourism destination.

For example, dating back to the Cold War era, Europe was conceptually (and to some extent physically) divided into an East and a West. To the American audience, “Europe” meant Western Europe. In contrast, areas behind the Iron Curtain in Eastern Europe came to be seen as a separate region colored by Cold War propaganda. This type of regional categorization presents things as black-and-white, but the reality of things is hardly this clear. The Cold War has been over for more than twenty years, but ideas about regions can take a long time to change. While tourism can help change people’s ideas about places through experience, it can also perpetuate patterns. In particular, widely used European guidebooks published by companies such as Rick Steves, Lonely Planet, Frommer’s, or Fodor’s only cover popular destinations in Western Europe in places such as England, France, and Spain. These companies also produce guides for Eastern Europe as a separate, less developed, and less distinguished destination region. As a result, Europe continues to be perceived as two distinct regions, even among the newest generation of tourists, who were born as the Cold War was ending.

This presents a challenge for the small European nation of Slovenia. It isn’t widely known in the American tourist market, which means that it is dependent on regional information to help potential tourists locate and identify it in their minds. Because the country was once part of Yugoslavia—and thus considered one of those areas behind the Iron Curtain—it isn’t included in the European guidebooks. Categorized as Eastern European, Slovenia is subject to the lingering negative perceptions about the region. In an effort to promote tourism to markets outside of Europe, the Slovenian Tourist Board has attempted to emphasize its Europeanness by highlighting its geographic location at the center of the European continent (map 1.1) and its attractions that are comparable to the other popular European destinations. This includes its coastal destinations on the Adriatic Sea with a Mediterranean climate and its mountain destinations in the Julian Alps near the borders with Austria and Italy (figure 1.2).

Discussion topic. What, if anything, comes to mind when you think about each of the following European regions: (a) Eastern Europe, (b) the Mediterranean, and (c) the Alps? How would your responses influence your decision to visit that region?

Tourism on the web\ Slovenian Tourist Board, “I Feel Slovenia: The Official Travel Guide,” at http://www.slovenia.info

Map 1.1. Slovenia. The Slovenian Tourism Board has worked to change westernized perspectives of the country as located in, and associated with traditional concepts of. Eastern Europe. Maps such as this deftly reshape perceptions of the European region to highlight Slovenia's central location. In fact, it makes popular European tourism destinations, such as Athens (Athina), Lisbon (Lisboa)—even London and Paris—seem peripheral. (Source. Gang Gong)

(continued)

Figure

1.2. Slovenia's Lake Bled, surrounded by the snow-capped mountains

of the Julian Alps, is one of the most popular tourism destinations

in the country. Moreover, this iconic image is so widely promoted

in both the country and regional tourism literature that it has

come to characterize Slovenia as a destination. (Source: Tom

Nelson)

Box

1.2. (continued)

Gilbert, Anne. “The New Regional Geography in English- and French-Speaking Countries.” Progress in Human Geography 12 (1988): 208-28.

Nelson, Velvet. “The Construction of Slovenia as a European Tourism Destination in Guidebooks.” Geoforum 43 (2012): 1099-1107.

Okey, Robin. “Central Europe/Eastern Europe: Behind the Definitions.” Past & Present 137 (1992): 102-33.

Cultural [ Geography , q(

\ Hitman Geography

Geography

Physical Geography

Geoiaorpbology

Figure 1.3. We can try to fit the topical branch of tourism geography into our graphic representation of the discipline. Based on what we know about tourism so far—that tourism is often seen as an activity or an industry—the argument could be made that the geography of tourism has a place between the major topical branches of cultural geography and economic geography.

Cultural Geography

Human Geography

Tourism

Geography

Physical Geography

Geoniatphotogy

Figure 1.4. If we adapt the graphic representation of geography for the geography of tourism, we can begin to appreciate all the components of tourism. Likewise, we can see how the topical structure of geography will allow us to break down and investigate this complex phenomenon.

Box

1.3. Terminology: Affect

and Effect

Box

1.3. Terminology: Affect

and Effect

Affect. Effect. The two words may sound the same when they are pronounced. There’s only a difference of one letter in the spelling. It probably doesn’t help that one is often used in the definition of the other. But that doesn’t mean they can be used interchangeably. They do, in fact, have different meanings, and they have distinct implications for our purposes in the geography of tourism.

We will be using affect is a verb. To affect is to act on or produce a change in something. We can use the topical branches of geography—on both the human and physical sides—to understand the factors that affect the tourism industry. For example, our understanding of climatology or political geography can help us understand how climatic hazards (e.g., hurricanes and cyclones) or geopolitical events (e.g., war and terrorism) have the potential to affect the tourism industry-—that is, to act on or produce a change in tourism. Any of these events have the potential to destroy the tourism infrastructure and prevent people from visiting a destination, at least for a while.

We will be using effect as a noun. An effect is something that is produced by an agency or cause; it is a result or a consequence. Again, we can use the topical branches of geography to understand what kinds of effects the tourism industry has. For example, our understanding of economic geography or environmental geography can help us understand the effects of tourism—that is, the results of tourism. The flow of income and investment into a place from the tourism industry may act as a catalyst for other types of development, or increased tourism development in fragile natural environments may cause environmental degradation.

Discussion topic. Pick a tourism destination and identify three factors that you think might affect tourism at that destination and three effects that you think tourism might have on that destination. What topical branches of geography would you use to examine each of these factors and effects?

For example, we can use the tools and concepts of climatology to help us understand tourism. Patterns of climate provide insight into things like tourism demand and supply and, by extension, tourist-generating and receiving regions. Winter vacations are often popular among people who live in the higher latitudes because long, cold winters generate a demand for the experience of a warm, sunny place. As such, cold climates are significant source areas for tourists, while tropical climates have long been significant destinations. Likewise, we can use the framework of political geography to provide insights into patterns of tourism. On a routine basis, politics and international relations create barriers to tourism between two places through visa requirements, complicated permits, and so on. Conversely, the removal of these barriers can create new opportunities. While geopolitical events like terrorism and armed conflicts will obviously have a direct impact on tourism for that destination, they can also have ripple effects on tourism throughout the world. After the events of September 11, 2001, there was an immediate decline in tourism to New York City and Washington, D.C., as well as a general decline in travel globally.

Who Are Tourism Geographers?

Tourism geographers are geographers. Geography provides us with the flexibility to study an incredible diversity of topics from a variety of perspectives. Although geographers specialize both regionally and topically in order to make the task of understanding the world more manageable, many geographers shun labels. Therefore, regardless of what we study, where, or how, we are geographers above all else. Geography provides the framework, or lens, through which we can view, explore, and understand various phenomena of the world in which we live. Second, labels are often unnecessarily restrictive. As discussed above, topical areas in geography do not stand alone; there is considerable overlap between them.

For some geographers, tourism is the primary theme in their research. Yet, these researchers will draw on various perspectives from different topical branches. These geographers are just as likely to be called cultural geographers, economic geographers, environmental geographers, or any other type of geographer for that matter, as they are to be called tourism geographers. In his report on the geography of tourism, Chris Gibson compiled a bibliography of academic articles on tourism written by geographers.11 His study found that the most common themes in these articles came from the areas of environmental geography, historical geography, and cultural geography.

For others, tourism may not be the primary theme or object of their work, but it is still a topic that has a distinct part to play. This is indicative of the fact that tourism is such a far-reaching phenomenon in today’s world. These geographers may never be called tourism geographers; however, their contributions to the geography of tourism should be considered important nonetheless. Gibson’s findings confirm that some of the most widely cited authors of papers on issues related to the geography of tourism do not list this as one of their topical specialties. He argues that geography is a discipline that allows researchers to work on some aspect of tourism, as it is situated within wider issues such as sustainability, poverty, changing patterns of land use, the rights of indigenous peoples, and others.

Finally, Gibson’s study explores where this research is coming from. Published geographic research has been dominated by the so-called Anglo-American regions of the world and particularly the United States and the United Kingdom. Although much research in the geography of tourism does, in fact, come from these areas, the proportion is considerably smaller than for geography as a whole. In contrast, the Australasia region, including Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore, has made some of the greatest contributions to the geography of tourism. Similarly, parts of Europe have also recognized the value of this research and have made key contributions to the field.