- •9.1. Trends in the Labor Force: the Last 50 Years

- •9.2. How are Wages Determined

- •9.3. How Nonmarket Forces Affect Wages

- •9.4. The Labor Movement in the United States

- •9.5. Labor Legislation and the Growth of Unions

- •9.6. Union-Management Relations in Action

- •9.7. Recent Developments in Labor-Management Relations

- •Wage Determination And The Basic Economic Questions

- •The Distribution Of Income

The Distribution Of Income

I ncome

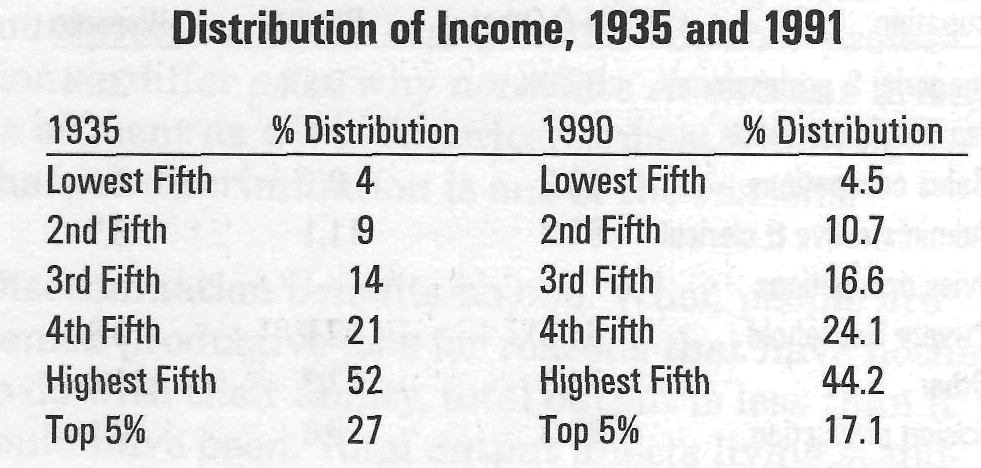

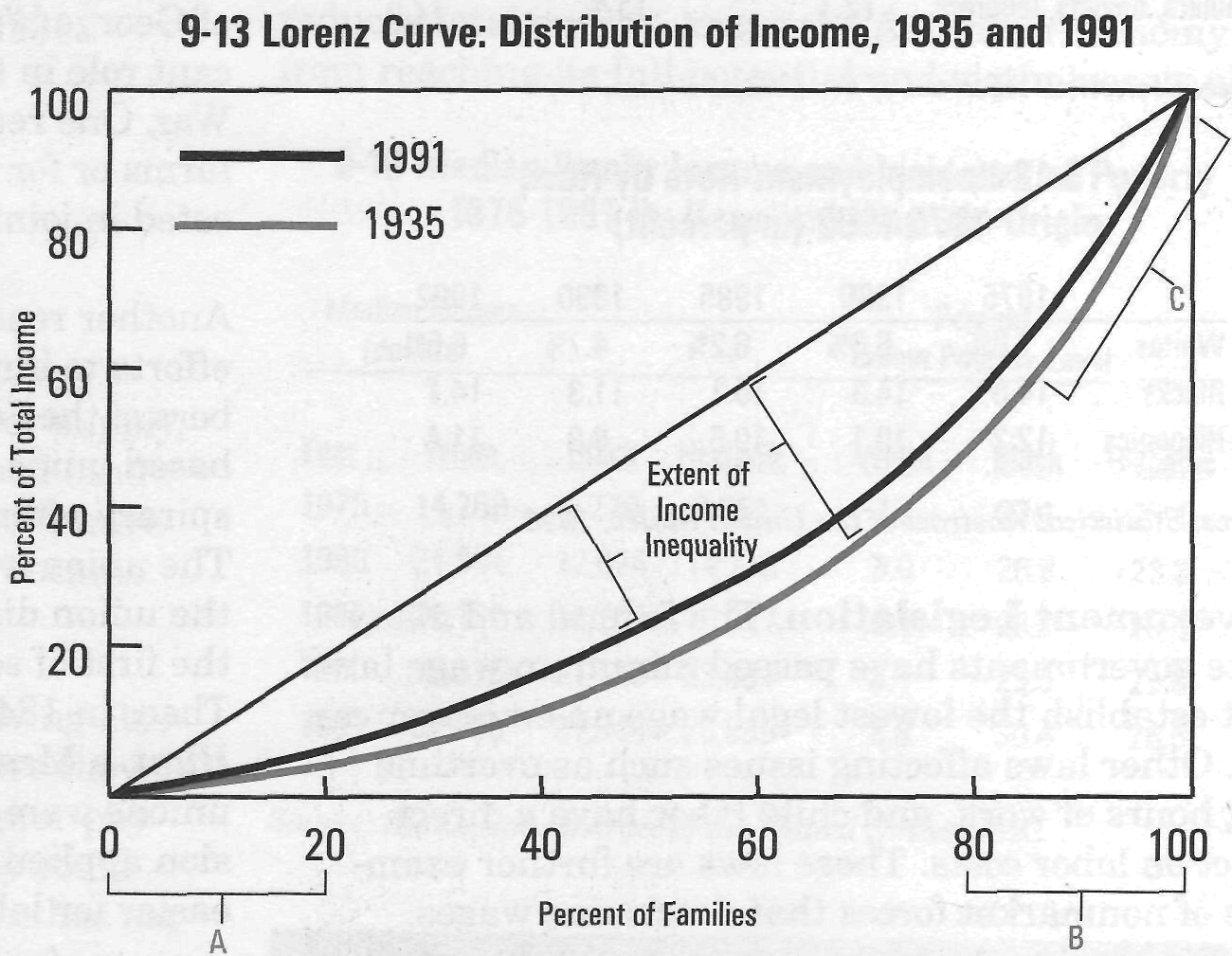

distribution can be represented in various ways. Graph 9-10 showed

median incomes, but 9-13 contains a Lorenz curve that better

illustrates the distribution of income, and its relative equality

(or inequality).

ncome

distribution can be represented in various ways. Graph 9-10 showed

median incomes, but 9-13 contains a Lorenz curve that better

illustrates the distribution of income, and its relative equality

(or inequality).

T he

diagonal line represents what income distribution would look

like if it were perfectly equal. That is, if 10 percent of the

population received 10 percent of the income, 20 percent

received 20 percent of income, and so on.

he

diagonal line represents what income distribution would look

like if it were perfectly equal. That is, if 10 percent of the

population received 10 percent of the income, 20 percent

received 20 percent of income, and so on.

The solid curved line (Lorenz curve) represents the actual distribution of income as summarized in the table for 1991. The red, curved line represents the data for 1935. Therefore, the area between the 45-degree line and the Lorenz curve represents the extent of inequality of income distribution for the two years. As indicated by this graph, income was somewhat more equally distributed in 1990 than it was 55 years earlier. Some economists believe this trend may be changing. Watch your newspaper for articles about shifts in the distribution of income.

Efforts to Organize Japanese Auto Plants in the U.S. Fails

In 1970, when Americans were buying approximately 7 million cars a year, the United Auto Workers (UAW) had 1.5 million members. By 1989, annual sales of new automobiles rose to over 10 million, but UAW membership fell to less than one million. One reason for the decline was the number of plant closings and layoffs that had occurred over those years. Another was the union's inability to organize newly opened Japanese automobile assembly plants.

In fact, in the summer of 1989 workers at the Nissan Motor Manufacturing Co. plant in Smyrna, Tennessee voted 1,622 to 711 against joining the union. Nissan, with 2,400 workers, was the fourth Japanese auto plant to resist union organization. The others were Honda, with a labor force of 7,000; Toyota with 2,500; and Subaru with 500.

The inability of the union to organize the Japanese-owned plants worries American manufacturers. Union workers are paid more than nonunion workers. The American companies fear that Japanese plants will be able to manufacture automobiles at a lower cost (and sell them at a lower price) than they can. As one Ford executive put it, the election results at Smyrna put the U.S. auto industry at a competitive disadvantage, because the nonunion workforce saved the Japanese companies several hundred dollars on the average cost per vehicle.

The History of Economic Thought

Samuel Gompers (1850-1924) America's First Great Labor Leader

Today's labor union movement is built on the foundation laid by Samuel Gompers, a poor Jewish immigrant from England. Arriving in America in 1863 at the age of 13, Gompers took a job in a cigar factory. In those days in cigar factories, one worker could read aloud while others worked. They read newspapers, magazines, books, and poetry. In this way Gompers and his fellow cigar makers received the education denied them when they left school to earn a living.

Being sympathetic to the goals of the Cigar Makers' Union, Gompers became an active member. By the 1880s, he was one of its principal leaders. Gompers reorganized the union to make it one of the nation's most powerful labor organizations. Before long, other unions began organizing like the Cigar Makers' Union. With his fame spreading, Gompers was encouraged to organize a federation of all the nation's craft unions. His efforts to form a national federation led to the creation, in 1886, of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Except for one term, Gompers served as president of the AFL from 1886 until his death in 1924. During that time its membership grew from 138,000 to more than 4 million. The AFL's growth in those years was due mostly to Gomper's reforms. Before the 1880s, labor unions often had tried to achieve their ends through political action. They sponsored candidates for federal, state, and local offices. Some even tried to form a political party to compete with the Democrats and Republicans. Others attempted to change the free enterprise system into some form of socialism. Gompers thought this political unionism was a terrible mistake.

Under Gompers, the AFL adopted a policy of business unionism. That is, they concentrated on getting higher wages and better working conditions for their members. Instead of organizing its own political party, or affiliating with an existing one, the AFL was more likely to support candidates of either major party friendly to their cause and oppose those whom they regarded as hostile.