- •989 Market Street, San Francisco, ca 94103-1741

- •Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

- •Part three: higher education blended learning models and perspectives 151

- •XXXIV Preface and Acknowledgments

- •34 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •38 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •Table 3.1. Blended learning train-the-trainer detailed agenda.

- •On designing interaction experiences for the next generation of blended learning

- •44 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •Interaction as Experience

- •In Support of Interaction Strategies for the Future of Blended Learning

- •Corporate blended learning models and perspectives

- •Blending learning for business impact

- •Ibm's Case for Learning Success

- •66 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •Guided Navigation

- •Figure 6.3. Specific learning elements.

- •Table 6.1. Learning elements.

- •Figure 6.6. Specific knowledge services.

- •Figure 7.3. Microsoft skills assessment tool for organizations.

- •Transformation of sales skills through knowledge management and blended learning

- •Figure 8.2. EsSba transformations in selling strategies.

- •116 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •Figure 9.1. Cisco networking academy organizational hierarchy.

- •41(8), 19. Wonacott, m. E. (2002). Blending face-to-face and distance learning methods in adult and career-technical

- •Table 10.1. Types of benefits identified in oracle's leadership training.

- •It also appeared to me that other people in the course weren't having as

- •Part three

- •Improve retention rates and student outcomes systemwide.

- •New zealand examples of blended learning

- •176 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •In addition to providing support to instructors through the multiple training opportunities listed above, some specific tools have been developed to support lecturers' needs:

- •Of glamorgan.

- •188 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •192 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •View.Asp?PressId::::75#top.

- •Blended learning enters the mainstream

- •Impact on Faculty and Students

- •200 The Handbook of Blended Learning

- •Integrated field experiences in online teacher education

- •A Natural Blend?

- •1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Fiscal Year (July 1-June 30)

- •Integrated Field Experiences in Online Teacher Education 217

- •In f. Murray (Ed.), The teacher educator's handbook. Building a knowledge base for the preparation of

- •Blended learning at the university of phoenix

- •School b.S. M.S. M.B.A. Ph.D. Psy.D.

- •Visits_040524.Html. Osguthorpe, r. Т., & Graham, c. R. (2003). Blended learning environments: Definitions and

XXXIV Preface and Acknowledgments

for-profit universities, blended learning models (in both higher education and corporate training), case examples of blended learning from around the world, workplace and authentic learning, and future trends in blended learning. The chapters discuss topics such as access, flexibility e-learning partnerships, enrollment demands, return on investment, online interaction, and strategic planning for blended learning. At the start of each part, we provide a brief introduction of the theme for that section, along with chapter synopses.

The chapter authors share specifics about what is happening in blended learning in their respective organization, institution, state, province, region, or country. They provide interesting data regarding trends in enrollments, new programs, technologies, and pedagogies. Some chapters discuss the unique or powerful aspects of a particular blended learning approach, including specific information on what is being blended and how successful that blend is. Others put forth models of blended learning that might be compared, adopted, and critiqued. And still others summarize the benefits, success stories, and return on investment from the blended strategies that they adopted, as well as the problems, challenges, and dilemmas still faced. In the end, this book contains a wide range of ideas, examples, guidelines, success stories, models, and solutions.

Acknowledgments

We thank the people at Pfeiffer Publishing for their help and support on this project, including Lisa Shannon, Laura Reizman, and Kathleen Dolan Davies. They were truly fantastic to work with. We thank the book reviewers for their insightful and informative suggestions. In addition, we deeply thank Mary, Alex, and Nicki Bonk and Dawn, Bobbe, Julie, William, Bethany, and Daniel Graham for their love, understanding, and encouragement during this project. As is usual with a project like this, there were countless late nights and several missed events. The first author would especially like to thank Robert Clasen, who, twenty years ago, roused his interest in distance learning as his teacher in two correspondence courses that qualified him for graduate school at the University of Wisconsin. Serendipity occurred when Bob and his wonderful wife, Donna Rae Clasen, later employed him in the production of a television-based correspondence course, Teachers Tackle Thinking, during his first couple of years in graduate school. Given the trends of the past two decades in distance learning, the mentoring and modeling that Bob provided within this field were extremely timely and fortuitous. You are the best, Bob! Finally, we thank all the chapter authors who each shed some light on the world of blended learning and show us opportunities that we may not have previously been aware of. It was truly a joy to work with each of you.

XXXV

Preface and Acknowledgments

References

Allen, E. I., & Seaman, J. (2003). Sizing the opportunity: The quality and extent of online education in the United States, 2002 and 2003. Needham and Wellesley, MA: Sloan Consortium. Retrieved August 21, 2005, from http://www.sloan-c.org/resources/

sizing_opportunity.pdf Bonk, G.J. (2004). The perfect e-storm: Emerging technologies, enhanced pedagogy, enormous learner

demand, and erased budgets. London: Observatory on Borderless Higher Education. Detweiler, R. (2004, July 9). At last, we can replace the lecture. Chronicle of Higher Education,

50(44), B8. National Center for Education Statistics. (2003). Distance education at degree-grantingpostsecondary

institutions: 2000-2001. Washington, DC: Department of Education. NGA Center for Best Practices. (2001). The state of e-learning in the states. Washington, DC:

National Governor's Association. Zemsky, R., & Massy, W. F. (2004, July 9). Why the e-learning boom went bust. Chronicle of

Higher Education, 50(44), B6. Bloomington, Indiana Curtis J. Bonk

Provo, Utah Charles R. Graham

October 2005

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION TO BLENDED LEARNING

As blended learning emerges as perhaps the most prominent delivery mechanism in higher education, business, government, and military settings, it is vital to define it, as well as explain where it is useful and why it is important. This part, with chapters by Charles R. Graham, Elliott Masie, Jennifer Hofmann, and Ellen D. Wagner, does just that. These authors discuss the elements that are important to consider in blended learning while also touching on some of the emerging trends and issues.

In Chapter One, Charles R. Graham describes the historical emergence of blended learning as the convergence between traditional face-to-face learning environments and computer-mediated (or distributed) learning environments. He discusses four critical dimensions to interactions that occur in both of these environments (space, time, fidelity, and humanness) and presents a working definition for blended learning systems. This chapter also addresses current trends seen in both corporate and higher education, including blends that focus on enabling access and flexibility enhancing current teaching and learning practices, and transforming the way individuals learn. The chapter ends with six important issues relevant to the design of blended learning systems, followed by some directions for the future.

In Chapter Two, Elliott Masie presents a brief and provocative perspective on blended learning. The central theme of his chapter is that all great learning is blended. In the predigital age, combinations of different learning contexts were

The Handbook of Blended Learning

used. Similarly, learning environments increasingly will incorporate "e elements" into varied instructional contexts. Masie outlines compelling reasons for why blending has been popular and will continue to be so.

In Chapter Three, Jennifer Hofmann addresses several of the typical challenges facing those who are attempting to implement blended solutions. She notes some of the common mistakes designers make: assuming that it will take less time to redesign an existing program than it would to design a blended program from scratch, putting too much emphasis on the "live" components of a training situation, and assuming that traditional facilitators are the best choices for managing a blended version of the training. An emphasis is placed on the importance of training the design team as well as the trainers. In addition, she outlines an example of a blended train-the-trainer course.

In Chapter Four, Ellen D. Wagner shares a vision for the next generation of blended learning. She addresses the impact that personal and mobile devices are likely to have on emerging models of blended learning and suggests that interaction strategies offer a useful means for enhancing individualization, personalization, and relevancy. She discusses current models of interaction and shares eleven ways that interaction can be used to focus on performance outcomes.

CHAPTER ONE

BLENDED LEARNING SYSTEMS

Definition, Current Trends, and Future Directions

Charles R. Graham

The term blended learning is being used with increased frequency in both academic and corporate circles. In 2003, the American Society for Training and Development identified blended learning as one of the top ten trends to emerge in the knowledge delivery industry (Rooney, 2003). In 2002, the Chronicle of Higher Education quoted the president of Pennsylvania State University as saying that the convergence between online and residential instruction was "the single-greatest unrecognized trend in higher education today" (Young, 2002, p. A33). Also quoted in that article was the editor of the Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, who predicted a dramatic increase in the number of hybrid (that is, blended) courses in higher education, possibly to include as many as 80 to 90 percent of all courses (Young, 2002).

So what is this blended learning that everyone is talking about? This chapter provides a basic introduction to blended learning systems and shares some trends and issues that are highly relevant to those who are implementing such systems. To accomplish these goals, the chapter addresses five important questions related to blended learning systems:

What is blended learning?

Why blend?

What current blended learning models exist?

What issues and challenges are faced when blending?

What are the future directions of blended learning systems?

3

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Background and Definitions

The first question asked by most people when hearing about blended learning is, "What is blended learning?" Although blended learning has become somewhat of a buzzword in corporate and higher education settings, there is still quite a bit of ambiguity about what it means (see Jones, Chapter Thirteen, this volume). How is blended learning different from other terms in our vernacular, such as distributed learning, e-learning, open and flexible learning, and hybrid courses? Some define the term so broadly that one would be hard pressed to find any learning system that was not blended (Masie, Chapter Two, this volume; Ross and Gage, Chapter Eleven, this volume). Others challenge the very assumptions behind blending as holding on to relics of an old paradigm of learning (Offerman and Tassava, Chapter Seventeen, this volume). In the first section of this chapter, I articulate a practical working definition for the term blended learning and provide a historical context for its emergence.

What Is Being Blended?

One frequent question asked when one hears about blended learning (BL) is, "What is being blended?" Although there is a wide variety of responses to this question (Driscoll, 2002), most of the definitions are just variations of a few common themes. The three most commonly mentioned definitions, documented by Graham, Allen, and Ure (2003), are:

Combining instructional modalities (or delivery media) (Bersin & Associates, 2003; Orey, 2002a, 2002b; Singh & Reed, 2001; Thomson, 2002)

Combining instructional methods (Driscoll, 2002; House, 2002; Rossett, 2002)

Combining online and face-to-face instruction (Reay, 2001; Rooney, 2003; Sands, 2002; Ward & LaBranche, 2003; Young, 2002)

The first two positions reflect the debate on the influences of media versus method on learning (Clark, 1983, 1994a, 1994b; Kozma, 1991, 1994). Both of these positions suffer from the problem that they define BL so broadly that they encompass virtually all learning systems. One would be hard-pressed to find any learning system that did not involve multiple instructional methods and multiple delivery media. So defining BL in either of these two ways waters down the definition and does not get at the essence of what blended learning is and why it is exciting to so many people. The third position more accurately reflects the historical emergence of blended learning systems and is the foundation of the author's working definition (see Figure 1.1).

Blended Learning Systems 5

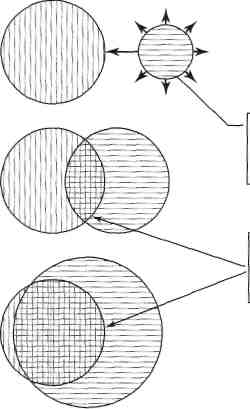

FIGURE 1.1. DEFINITION OF BLENDED LEARNING SYSTEMS.

Definition:

Blended learning systems combine face-to-face instruction with computer-mediated instruction.

The working definition in Figure 1.1 reflects the idea that BL is the combination of instruction from two historically separate models of teaching and learning: traditional face-to-face learning systems and distributed learning systems. It also emphasizes the central role of computer-based technologies in blended learning.

Past, Present, and Future

BL is part of the ongoing convergence of two archetypal learning environments. On the one hand, we have the traditional face-to-face learning environment that has been around for centuries. On the other hand, we have distributed learning environments that have begun to grow and expand in exponential ways as new technologies have expanded the possibilities for distributed communication and interaction.

In the past, these two learning environments have remained largely separate because they have used different media and method combinations and have addressed the needs of different audiences (see Figure 1.2). For example, traditional face-to-face learning typically occurred in a teacher-directed environment with person-to-person interaction in a live synchronous, high-fidelity environment. On the other hand, distance learning systems emphasized self-paced learning and learning materials interactions that typically occurred in an asynchronous, low-fidelity (text only) environment.

Figure 1.3 shows the continuum for four critical dimensions of interactions that occur in both of these environments. Historically, face-to-face learning has operated at the left-hand side of each of these dimensions, and distributed learning has operated at the right of each of these dimensions. To a large degree, the media available placed constraints on the nature of the instructional methods that could be used in each environment. For example, it was not possible to have synchronous or high-fidelity interactions in the distributed environment. Because of these constraints, distributed learning environments placed emphasis on learner-material interactions, while face-to-face learning environments tended to place priority on the human-human interaction.

The Handbook of Blended Learning

FIGURE 1.2. PROGRESSIVE CONVERGENCE OF TRADITIONAL

FACE-TO-FACE AND DISTRIBUTED ENVIRONMENTS ALLOWING

DEVELOPMENT OF BLENDED LEARNING SYSTEMS.

Traditional Distributed

face-to-face (computer-mediated)

Learning Environment Learning Environment

Expansion

due to

technological innovation

(largely separate systems)

Present (increasing implementation of blended systems)

Future

(majority of blended systems)

Blended Learning System

The rapid emergence of technological innovations over the past half-century (particularly digital technologies) has had a huge impact on the possibilities for learning in the distributed environment. In fact, if you look at the four dimensions, distributed learning environments are increasingly encroaching on instructional territory that was once possible only in face-to-face environments. For example, in the time and fidelity dimensions, communication technologies now allow us to have synchronous distributed interactions that occur in real time with close to the same levels of fidelity as in the face-to-face environment. In the humanness dimension, there is an increasing focus on facilitating human interaction in the form of computer-supported collaboration, virtual communities, instant messaging, and blogging. In addition, there is ongoing research investigating how to make machines and computer interfaces more social and human (the work with automated agents and virtual worlds, for example). Even in the space dimension, there are some interesting things happening with mixed reality environments (see Kirkley and Kirkley, Chapter Thirty-Eight, this volume) and environments that

Blended Learning Systems

7

FIGURE 1.3. FOUR DIMENSIONS OF INTERACTION IN

FACE-TO-FACE AND DISTRIBUTED

LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS.

Space

Time

Fidelity

Humanness

Live |

|

|

(physical/ face-to-face) |

Mixed Reality |

Virtual (distributed) |

Live Synchronous (very short lag time) |

|

Asynchronous (long lag time) |

|

Medium |

|

High (rich all senses) |

(for example, audio only) |

Low (text only) |

High Human |

|

No Human |

No Machine |

|

High Machine |

simultaneously facilitate both distributed and face-to-face interactions (see Wisher, Chapter Thirty-Seven, this volume).

The widespread adoption and availability of digital learning technologies has led to increased levels of integration of computer-mediated instructional elements into the traditional face-to-face learning experience. From the distributed learning perspective, we see evidence of the convergence in face-to-face residency requirements (Offerman and Tassava, Chapter Seventeen, this volume; Pease, Chapter Eighteen, this volume) and limited face-to-face events, such as orientations and final presentations (Lindquist, Chapter Sixteen, this volume). In addition, there is greater emphasis on person-to-person interaction, and increasing use of synchronous and high-fidelity technologies to mediate those interactions. Figure 1.2 depicts the rapid growth of distributed learning environments and its convergence with face-to-face learning environments. The intersection of the two archetypes depicts where blended learning systems are emerging.

Although it is impossible to see entirely what the future holds, we can be pretty certain that the trend toward blended learning systems will increase. It may even become so ubiquitous that we will eventually drop the word blended and just call it learning, as both Masie (see Chapter Two, this volume) and Massy (see Chapter Thirty, this volume) predict. But regardless of what we decide to call blended

8

The Handbook of Blended Learning

learning in the future, it is clear that it is here to stay. Therefore, it is imperative that we understand how to create effective blended learning experiences that incorporate both face-to-face and computer-mediated (CM) elements.

Current Trends and Issues

Here we look at current trends and issues that are relevant to blended learning systems.

Why Blend?

There are many reasons that an instructor, trainer, or learner might pick blended learning over other learning options. Osguthorpe and Graham (2003) identified six reasons that one might choose to design or use a blended learning system: (1) pedagogical richness, (2) access to knowledge, (3) social interaction, (4) personal agency, (5) cost-effectiveness, and (6) ease of revision. In the BL literature, the most common reason provided is that BL combines the best of both worlds. Although there is some truth to this, it is rarely acknowledged that a blended learning environment can also mix the least effective elements of both worlds if it is not designed well. Beyond this general statement, Graham, Allen, and Ure (2003, 2005) found that, overwhelmingly, people chose BL for three reasons: (1) improved pedagogy, (2) increased access and flexibility, and (3) increased cost-effectiveness.

Improved Pedagogy. One of the most commonly cited reasons for blending is more effective pedagogical practices. It is no secret that most current teaching and learning practice in both higher education and corporate training settings is still focused on transmissive rather than interactive strategies. In higher education, 83 percent of instructors use the lecture as the predominant teaching strategy (U.S. Department of Education, 2001). Similarly, distance education often suffers from making large amounts of information available for students to absorb independently (Waddoups & Howell, 2002). Some have seen blended learning approaches increase the level of active learning strategies, peer-to-peer learning strategies, and learner-centered strategies used (Collis, Bruijstens, & van der Veen, 2003; Hartman, Dziuban, & Moskal, 1999; Morgan, 2002; Smelser, 2002). There are many examples of this in this handbook, including the model used by IBM (Lewis and Orton, Chapter Five, this volume) where learners go through three phases: (1) online self-paced learning to acquire background information, (2) face-to-face learning lab focused on

Blended Learning Systems

9

active learning and application experiences instead of lecture, and (3) online learning and support for transferring the learning to the workplace environment. Using a similar strategy, a Brigham Young University accounting professor uses online modules to help students acquire the tool-related skills and technical information and then uses precious face-to-face class time to focus on application, case studies, and develop decision-making skills (Cottrell & Robison, 2003). It is interesting to note such overlaps in blended learning models between the corporate training world and higher education.

A few other ideas for using BL to improve pedagogy included in this handbook are provided by Oliver, Herrington, and Reeves (Chapter Thirty-Six, this volume), who provide insights into how computer-mediated environments can bring a level of authenticity to the traditional classroom experience. Collis (see Chapter Thirty-Three, this volume) shares a model for how BL can be used to integrate formal classroom learning and informal workplace learning. Wisher (Chapter Thirty-Seven this volume) and Kirkley and Kirkley (see Chapter Thirty-Eight, this volume) share ideas for collaborative learning and problem solving in environments that mix live face-to-face elements with virtual reality.

Increased Access and Flexibility. Access to learning is one of the key factors influencing the growth of distributed learning environments (Bonk, Olson, Wisher, & Orvis, 2002). Many chapters in this book emphasize programs that would not be possible if students were not able to have a majority of their learning experiences at a distance from instructors and/or other students (for examples, see Kaur and Ahmed, Chapter Twenty-Two; Lee and Im, Chapter Twenty; Reynolds and Greiner, Chapter Fifteen, this volume). Learner flexibility and convenience are also of growing importance as more mature learners with outside commitments such as work and family seek additional education. Many learners want the convenience offered by a distributed environment yet do not want to sacrifice the social interaction and human touch they are used to in a face-to-face classroom. There are numerous examples in this handbook of how blending is used to provide a balance between flexible learning options and the high-touch human interactive experience. WebCT executives Barbara Ross and Karen Gage (Chapter Eleven, this volume), for example, have seen an expansion of reduced seat-time courses that allow increased flexibility but retain some traditional face-to-face contact. The University of Central Florida's M (i.e., mixed mode) courses (Dziuban, Hartman, Juge, Moskal, and Sorg, Chapter Fourteen, this volume) are also good examples. As a third example, the University of Phoenix model allows face-to-face socializing in orientations as well as presentation experiences at the beginning and ending of a course, with online learning experiences in between (see Chapter Sixteen, this volume).

10

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Increased Cost-Effectiveness. Cost-effectiveness is a third major goal for BL systems in both higher education and corporate institutions. Blended learning systems provide an opportunity for reaching a large, globally dispersed audience in a short period of time with consistent, semipersonal content delivery. Bersin and Associates (2003) have done an exemplary job of documenting corporate cases that have effectively used blended learning to provide a large return on investment (ROI). Similarly, in this handbook, the IBM chapter by Lewis and Orton reports ROI figures as high as 47 to 1 for their implementation of BL. In adding to these results, the Avaya chapter (Chute, Williams, and Hancock, Chapter Eight, this volume) and Microsoft chapter (Ziob and Mosher, Chapter Seven, this volume) provide cases in which BL solutions have resulted in a significant ROI.

In higher education, there is also interest in finding solutions that are cost-effective. The Center for Academic Transformation with support from the Pew Charitable Trust recently completed a three-year grant program designed to help universities explore ways of using technology to achieve quality enhancements and cost savings simultaneously. More detailed information for each of the thirty grant redesign projects that Pew funded can be found at the grant Web site (Pew, 2003). A summary of the significant role blended learning played in the various Pew projects can be found in Graham and Allen (Graham, Allen, & Ure, 2003, 2005).

Part Two of this handbook on for-profit universities has several chapters that address this issue (Pease, Chapter Eighteen, this volume). The University of Central Florida, for example, has predicted cost savings due to cost reductions in physical infrastructure and improved scheduling efficiencies, which have yet to materialize (Dziuban, Hartman, Juge, Moskal, and Sorg, Chapter Fourteen, this volume).

What Models of Blending Exist?

One of the goals of this handbook is to look broadly across many sectors to see what the current state of blended learning is and what we can learn from innovative people and organizations in this arena. This book provides a wide range of perspectives and flavors of blended learning to learn from. Although there is a wide variance in the blended learning practices that are occurring, there are also some strategic similarities that will be articulated in following section.

Blending at Many Different Levels

All of the BL examples in this handbook occur at one of the following four levels: activity level, course level, program level, or institutional level. Several chapters

Blended Learning Systems

11

(Ross and Gage, Chapter Eleven, this volume; Wright, Dewstow, Topping, and Tappenden, Chapter Twelve, this volume) specifically address different levels of blending that are occurring. Across all four levels, the nature of the blends is determined by the learner or the designer or instructor. Blending at the institutional and program levels is often left to the discretion of the learner, while designers and instructors are more likely to take a role in prescribing the blend at the course and activity levels.

Activity-Level Blending. Blending at the activity level occurs when a learning activity contains both face-to-face and CM elements. For example, Wisher (Chapter Thirty-Seven, this volume) outlines large-scale military training events that incorporate both face-to-face and virtual elements. Kirkley and Kirkley (Chapter Thirty-Eight, this volume) also discuss how mixed reality technologies blend the virtual and the real together during learning activities. In higher education, Oliver, Herrington, and Reeves (Chapter Thirty-Six, this volume) talk about strategies for using technological tools to make learning activities more authentic, while examples like those of Jung and Suzuki (Chapter Nineteen, this volume) share how technology is used to bring experts at a distance into the classroom, creating a simultaneous face-to-face and CM experience.

Course-Level Blending. Course-level blending is one of the most common ways to blend. It entails a combination of distinct face-to-face and CM activities used as part of a course. Some blended approaches engage learners in different but supportive face-to-face and CM activities that overlap in time, while other approaches separate the time blocks so that they are sequenced chronologically but not overlapping (see the examples in Huang and Zhou, Chapter Twenty-One, this volume, andjagannathan, Chapter Thirty-Two, this volume). Owston, Garrison, and Cook (Chapter Twenty-Four, this volume) describe eight cases of blending at the course level across universities in Canada. Collis (Chapter Thirty-Three, this volume) describes an approach to course-level blending for a suite of courses used by Shell EP.

Program-Level Blending. Ross and Gage (Chapter Eleven, this volume) observe that blends in higher education are often occurring at the degree program level. Blending at a program level often entails one of two models: a model in which the participants choose a mix between face-to-face courses and online courses or one in which the combination between the two is prescribed by the program. Jung and Suzuki (Chapter Nineteen, this volume) discuss a program-level blend in the Japan context in which there are certain face-to-face courses that are required for a program and the rest can be taken at a distance. Salmon and Lawless (Chapter Twenty-Eight, this volume) describe a business management certificate

The Handbook of Blended Learning

program that allows students the choice of completing the program completely online or online with face-to-face tutoring session or participation in an extended on-campus management challenge. The New Zealand Law Diploma program is conducted mostly online, with about 15 percent of the learning time in a face-to-face setting. Reynolds and Greiner (Chapter Fifteen, this volume) and Wright, Dewstow, Topping, and Tappenden (Chapter Twelve, this volume) describe teacher education programs that blend face-to-face and CM experiences at the program level.

In the corporate arena, BL is often applied to a particular training program, as was the case with Oracle's Leader Track training (Hanson and Clem, Chapter Ten, this volume), Avaya's Executive Solutions Selling Business Acumen program (Chute, Williams, and Hancock, Chapter Eight, this volume), and cases of three training programs provided by Microsoft (Ziob and Mosher, Chapter Seven, this volume).

Institutional-Level Blending. Some institutions have made an organizational commitment to blending face-to-face and CM instruction. Many corporations as well as institutions of higher education are creating models for blending at an institutional level. IBM (Lewis and Orton, Chapter Five, this volume) and Sun Microsystems (Wenger and Ferguson, Chapter Six, this volume) are corporate examples of organizations with institutional models of blended learning. The University of Phoenix (Lindquist, Chapter Sixteen, this volume) also has an institutional model for blending, where students have face-to-face classes at the beginning and end of the course, with online activities in between. At a university level, the University of Central Florida (Dziuban, Hartman, Juge, Moskal, and Sorg, Chapter Fourteen, this volume) has created the "M course" designation for blended courses that have some reduction in face-to-face seat-time. Other institutions, such as Brigham Young University (BYU) Idaho, have a general education requirement that students must have one online learning course experience to graduate (BYUTdaho, 2004). Brigham Young University (Provo campus) has experimented with "semester online" courses where on-campus students can enroll for a distributed course along with other campus-based courses (Waddoups & Howell, 2002). Similarly, at the University of Illinois, traditional on-campus economics students have been allowed to take a required course online while they were off-campus for the summer (Wang, Kanfer, Hinn, & Arvan, 2001).

It is important to note that dual-mode institutions (Rumble, 1992) that support both face-to-face and CM instruction are not necessarily in the business of blending learning. For the institution to be engaged in blended learning, there must be a concerted effort to enable the learner to take advantage of both ends

Blended Learning Systems

13

of the spectrum. It is not sufficient for the institution to have a distance learning division that is largely separate from the on-campus operations.

General Categories of Blends

One of the reasons that we are interested in models of blended learning is that we are interested in the practical question, "How to blend?" Each model provides ideas about how to blend with examples implemented in specific contexts and with real constraints. Table 1.1 provides three categories for blended learning systems found in this handbook based on the primary purpose of the blend. Some blends in this handbook fit into multiple categories; however, usually a blend most closely matches the focus of one category. It is also important to note that none of these blends is necessarily bad; they just have different foci.

We see the greatest focus on enabling blends in programs that come out of a distance learning tradition. A good example is the University of Phoenix (Lindquist, Chapter Sixteen, this volume), which attempts to provide an "equivalent" learning experience through its face-to-face residential programs, entirely online programs, and blended learning programs. In this system, learners pick the option that best meets their cost and time constraints.

There is an enormous focus on enhancing blends in traditional university settings. With the widespread adoption of learning management systems (LMS) and

TABLE 1.1. CATEGORIES OF BLENDED LEARNING SYSTEMS.

Enabling blends Primarily focus on addressing issues of access and

convenience—for example, blends that are intended to provide additional flexibility to the learners or blends that attempt to provide the same opportunities or learning experience but through a different modality.

Enhancing blends Allow incremental changes to the pedagogy but do not

radically change the way teaching and learning occurs. This can occur at both ends of the spectrum. For example, in a traditional face-to-face learning environment, additional resources and perhaps some supplementary materials may be included online.

Transforming blends Blends that allow a radical transformation of the

pedagogy—for example, a change from a model where learners are just receivers of information to a model where learners actively construct knowledge through dynamic interactions. These types of blends enable intellectual activity that was not practically possible without the technology.

14

The Handbook of Blended Learning

technology-equipped classrooms, it is becoming increasingly commonplace for instructors to use some level of technology. Both Jones (Chapter Thirteen, this volume) and Wright, Dewstow, Topping, and Tappenden (Chapter Twelve, this volume) provide models that span the spectrum from a minimum level of integration to a high level of integration. The hope of some is that enhancing blends are the first steps toward more transformative blends.

There seems to be a greater abundance of examples of transforming blends in the corporate environment than in the university environment. Examples like the Live-Virtual-Constructive simulations (Wisher, Chapter Thirty-Seven, this volume) and mixed-reality and problem-based embedded training (Kirkley and Kirkley, Chapter Thirty-Eight, this volume) show how high-end technologies can transform the learning experience. Other examples include the increased use of knowledge management, electronic performance support systems, and mobile devices to situate learning in the context of work flow (see Chute, Williams, and Hancock, Chapter Eight; Collis, Chapter Thirty-Three; DeViney and Lewis, Chapter Thirty-Five; and Singh, Chapter Four, this volume). In higher education environments, constraints such as class duration, size, location, and availability of technology can provide a formidable barrier to making transformative changes. Oliver, Herrington, and Reeves (Chapter Thirty-Six, this volume), for instance, point to several ways that technology can support the development of authentic learning environments. A growing number of faculty are experimenting with innovative technology-mediated approaches to teaching (such as the use of tools for simulations, visualization, communication, and feedback) that are transforming the ways that their students learn (West & Graham, 2005).

What Issues or Challenges Are Faced When Blending?

Six major issues are relevant to designing blended learning systems: (1) the role of live interaction, (2) the role of learner choice and self-regulation, (3) models for support and training, (4) finding balance between innovation and production, (5) cultural adaptation, and (6) dealing with the digital divide.

The Role of Live Interaction. Under what conditions is human interaction important to the learning process and to learner satisfaction with the process? Hanson and Clem, Chapter Ten; Hofmann, Chapter Three; and Owston, Garrison, and Cook, Chapter Twenty-Four, among others (this volume) observed a preference among many learners for the live (or face-to-face) components of a blended experience. When CM and face-to-face elements were combined, learners often placed a greater value or emphasis on the face-to-face aspects of the experience. Juxtaposed to this, Offerman and Tassava (Chapter Seventeen, this volume) make the claim that the

Blended Learning Systems

T5

face-to-face components are unnecessary and primarily used for socialization reasons. Similarly, the University of Phoenix (Lindquist, Chapter Sixteen, this volume) takes the position that the live, completely online, and blended options to its courses are "equivalent" experiences to be selected based on learner preference. When and why should we be considering human interaction such as collaboration and learning communities? How does live interaction versus low-fidelity, asynchronous interaction affect the learning experience?

Role of Learner Choice and Self-Regulation. How are learners making choices about the kinds of blends that they participate in? Many of the chapters in this book as well as other blended learning publications make it seem that learners are primarily selecting blended learning based on convenience and access. But this begs questions about the type and amount of guidance that should be provided to learners in making their choices about how different blends might affect their learning experience. Online learning components often require a large amount of self-discipline on the part of the learners (Collis, Bruijstens, & van der Veen, 2003). Huang and Zhou (Chapter Twenty-One,this volume) mention the challenge that many of their Chinese students have in regulating their own learning without the close guidance of an instructor. How can blended learning environments be designed to support increasing learner maturity and capabilities for self-regulation?

Models for Support and Training. There are many issues related to support and training in blended environments, including (1) increased demand on instructor time (Hartman et al., 1999; Lee and Im, Chapter Twenty, this volume), (2) providing learners with technological skills to succeed in both face-to-face and CM environments (Levine & Wake, 2000; Morgan, 2002), and (3) changing organizational culture to accept blended approaches (Hartman et al., 1999). There is also a need to provide professional development for instructors who will be teaching online and face-to-face (Lee and Im, Chapter Twenty, this volume; Lindquist, Chapter Sixteen, this volume). It is important to see more successful models of how to support a blended approach to learning from the technological infrastructure perspective as well as from the organizational (human) perspective.

Digital Divide. The divide between the information and communication technologies available to individuals and societies at different ends of the socioeconomic spectrum can be great (see chapters by Massy, Chapter Thirty; Jagannathan, Chapter Thirty-Two; and Kaur and Ahmed, Chapter Twenty-Two, this volume). Massy raises the issue that e-learning is often perceived as being an approach that favors the advantaged. Yet e-learning is a strategy that might be considered for

16

The Handbook of Blended Learning

educating the masses because of its low cost and ability to be distributed widely. But the jury is still out on whether blended learning models can be developed that are affordable and still address the needs of different populations with different socioeconomic conditions around the world.

Cultural Adaptation. What role can and should blended approaches play in adapting materials to local audiences? One strength of e-learning is the ability to distribute uniform learning materials rapidly. Yet there is often a need for customizing the materials to the local audience to make them culturally relevant. Jagannathan (Chapter Thirty-Two, this volume) and Selinger (Chapter Thirty-One, this volume) both address the need to find balance between global and local interests. Selinger suggests that a face-to-face instructor plays an important role in helping to make globally distributed materials culturally relevant and meaningful.

Balance Between Innovation and Production. In design, there is a constant tension between innovation and production. On the one hand, there is a need to look to the possibilities that new technological innovations provide, and, on the other hand, there is a need to be able to produce cost-effective solutions. However, due to the constantly changing nature of technology, finding an appropriate balance between innovation and production will be a constant challenge for those designing blended learning systems.

Directions for the Future

We live in a world in which technological innovation is occurring at breakneck speed and digital technologies are increasingly becoming an integral part of our lives. Technological innovation is also expanding the range of possible solutions that can be brought to bear on teaching and learning. Whether we are primarily interested in creating more effective learning experiences, increasing access and flexibility, or reducing the cost of learning, it is likely that our learning systems will provide a blend of both face-to-face and CM experiences.

Ross and Gage (Chapter Eleven, this volume) state that future learning systems will be differentiated not based on whether they blend but rather by how they blend. This question of how to blend face-to-face and CM instruction effectively is one of the most important we can consider. Like any other design problem, this challenge is highly context dependent, with a practically infinite number of possible solutions. So in this handbook we do not present any one solution as the solution; rather, we share examples of successful blends across many contexts. We hope that the wide range of global perspectives and specific local examples

Blended Learning Systems

17

FIGURE 1.4. THE CHALLENGE OF FINDING BLENDS THAT TAKE

ADVANTAGE OF THE STRENGTHS OF EACH ENVIRONMENT

AND AVOID THE WEAKNESSES.

Strengths of Environment

Desirable

Face-to-Face

Learning Environment

Blending

Technology Mediated and Face-to-Face

Technology Mediated Learning

Environment

Undesirable

Weaknesses of Environment

available in this handbook will help readers gain a better understanding of options for meeting instructional design challenges in varied contexts. Our charge is to try and understand the strengths and weaknesses of both face-to-face and CM environments so that when we are faced with trade-offs, we can make appropriate decisions. Figure 1.4 is a simplified representation of this complex challenge. From a pedagogical standpoint, the designers of blending learning systems should be seeking best practices for how to combine instructional strategies in face-to-face and CM environments that take advantages of the strengths of each environment and avoid their weaknesses (Osguthorpe & Graham, 2003; Martyn, 2003).

To illustrate the importance of understanding the strengths and weaknesses afforded by a face-to-face or CM learning environment, consider the following example of an activity-level blend. Class discussions are one of the most common instructional methods used in education. Unlike the lecture, the instructional method of class discussion focuses on learner interaction rather than knowledge transmission. Typically, the goal of class discussion is to have the learners negotiate and co-construct an understanding of the discussion topic. The face-to-face and CM environments have many complementary strengths and weaknesses that impact class discussion. Table 1.2 lists some of the strengths and weaknesses of conducting discussions in each of these environments.

18

The Handbook of Blended Learning

TABLE 1.2. STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES OF CONDUCTING

DISCUSSIONS IN FACE-TO-FACE AND COMPUTER-MEDIATED

LEARNING ENVIRONMENTS.

Computer-Mediated Environment (Asynchronous Text-Based Discussion)

Face-to-Face Environment (In-Class Discussion)

Strengths

Weaknesses

Flexibility: Students can contribute to the discussion at the time and place that is most convenient to them.

Participation: All students can participate because time and place constraints are removed.

Depth of reflection: Learners have time to more carefully consider and provide evidence for their claims and provide deeper, more thoughtful reflections (Mikulecky, 1998; Benbunan-Fich & Hiltz, 1999).

Spontaneity: Does not encourage the generation of rapid chains of associated ideas and serendipitous discoveries (Mikulecky, 1998).

Procrastination: There may be a tendency toward procrastination (Benbunan-Fich & Hiltz, 1999).

Human connection: The medium is considered to be impersonal by many (Benbunan-Fich & Hiltz, 1999), which may cause a lower satisfaction level with the process (Haytko, 2001).

Human connection: It is easier to bond and develop a social presence in a face-to-face environment. This makes it easier to develop trust.

Spontaneity: Allows the generation of rapid chains of associated ideas and serendipitous discoveries (Mikulecky, 1998).

Participation: Cannot always have everyone participate, especially if there are dominating personalities.

Flexibility: Limited time, which means that you may not be able to reach the discussion depth that you would like.

Although Table 1.2 certainly does not contain all of the possible strengths and weaknesses of conducting discussions in the face-to-face and CM environments, instructors might use this understanding to make decisions about whether to use one or the other or both learning environments to meet instructional goals. For example, by understanding the affordances of face-to-face and CM environments, an instructor of a large-enrollment class might choose to use the CM environment so that everyone in the class can contribute to the discussion. Another instructor concerned about unmotivated students and procrastination might choose to use a face-to-face discussion where social presence and excitement for the topic can be communicated through voice as well as gesture. A third instructor might choose to blend the two learning environments, starting with a brief exploratory

Blended Learning Systems

19

face-to-face discussion to generate excitement for the topic and set the stage for a more in-depth follow-up discussion online in a CM environment.

As we move into the future it is important that we continue to identify successful models of blended learning at the institutional, program, course, and activity levels that can be adapted to work in contexts. This effort will involve understanding and capitalizing on the unique affordances available in both face-to-face and computer-mediated or distributed learning environments.

References

Benbunan-Fich, R., & Hiltz, S. R. (1999). Educational applications of CMCS: Solving

case studies through asynchronous learning networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, 4(3). Retrieved July 12, 2005, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol4/issue3/

benbunan-fich.html. Bersin & Associates. (2003). Blended learning: What works? An industry study of the strategy,

implementation, and impact of blended learning. Oakland, CA: Bersin & Associates. Bonk, G. J., Olson, Т., Wisher, R. A., & Orvis, K. L. (2002). Learning from focus groups'. An

examination of blended learning. Journal of Distance Education, 17(3), 97-118. BYU-Idaho. General education requirement. BYU Idaho. Retrieved October 30, 2004, from

http://www.byui.edu/catalog/2001-2002/GeneralEd.htm. Clark, R. E. (1983). Reconsidering research on learning from media. Review of Educational

Research, 55(4), 445-459. Clark, R. E. (1994a). Media and method. Educational Technology Research and Development, 42(3),

7-10. Clark, R. E. (1994b). Media will never influence learning. Educational Technology Research and

Development, 42(2), 21-29. Collis, В., Bruijstens, H., & van der Veen, J. K. (2003). Course redesign for blended learning:

Modern optics for technical professionals. International Journal of Continuing Engineering

Education and Lifelong Learning, 15(1/2), 22—38. Cottrell, D., & Robison, R. (2003). Blended learning in an accounting course. Quarterly Review

of Distance Education, 4(3), 261-269. Driscoll, M. (2002, March 1). Blended learning: Let's get beyond the hype, e-learning.

http://www.ltimagazine.com/ltimagazine/article/articleDetail.jsp?id= 11755.Graham, C.

R., & Allen, S. (2005). Blended learning: An emerging trend in education. In C. Howard,

J. V Boettecher, L. Justice, K. D. Schenk, P. L. Rogers, & G. A. Berg (Eds.), Encyclopedia of

distance learning (pp. 172-179). Hershey, PA: Idea Group. Graham, C. R., Allen, S., & Ure, D. (2003). Blended learning environments: A review of the research

literature. Unpublished manuscript, Provo, UT. Graham, C. R., Allen, S., & Ure, D. (2005). Benefits and challenges of blended learning

environments. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Encyclopedia of information science and technology

(pp. 253-259). Hershey, PA: Idea Group. Hartman,J. L., Dziuban, C, & Moskal, P. (1999, August 16-18). Faculty satisfaction inALNs:A

dependent or independent variable? Paper presented at the Sloan Summer ALN Workshops,

Learning Effectiveness and Faculty Satisfaction, Urbana, IL.

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Haytko, D. L. (2001). Traditional versus hybrid course delivery systems: A case study of

undergraduate marketing planning courses. Marketing Education Review, 11(3), 27-39. House, R. (2002, January 8). Clocking in column. Spokesman-Review. Kozma, R. B. (1991). Learning with media. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 179-211. Kozma, R. B. (1994). Will media influence learning? Reframing the debate. Educational

Technology Research and Development, 42(2), 7-19. Levine, S. L., & Wake, W. K. (2000, October 20). Hybrid teaching: Design studios in virtual space.

Paper presented at the National Conference on Liberal Arts and the Education of Artists,

School of Visual Arts, New York. Martyn, M. (2003). The hybrid online model: Good practice. Educause Quarterly, 26(1), 18—23. Mikulecky, L. (1998). Diversity, discussion, and participation: Comparing Web-based and

campus-based adolescent literature classes. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 42(2),

84-97. Morgan, K. R. (2002). Blended learning: A strategic action plan for a new campus. Seminole:

University of Central Florida. Orey, M. (2002a). Definition of blended learning. University of Georgia. Retrieved February 21,

2003, from http://www.arches.uga.edu/~mikeorey/blendedLearning. Orey, M. (2002b). Oneyear of online blended learning: Lessons learned. Paper presented at the

Annual Meeting of the Eastern Educational Research Association, Sarasota, FL. Osguthorpe, R. Т., & Graham, C. R. (2003). Blended learning systems: Definitions and

directions. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 4(3), 227-234. Pew. (2003). Program in course redesign. Center for Academic Transformation. Retrieved August,

20, 2003, from http://www.center.rpi.edu/PewGrant.html. Reay, J. (2001). Blended learning—a fusion for the future. Knowledge Management Review,

4(3), 6. Rooney, J. E. (2003). Blending learning opportunities to enhance educational programming

and meetings. Association Management, 55(5), 26-32. Rossett, A. (2002). The ASTD e-learning handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill. Rumble, G. (1992). Open learning. Open Learning, 7(2), 31-45.

Sands, P. (2002). Inside outside, upside downside: Strategies for connecting online and face-to-face instruction in hybrid courses. Teaching with Technology Today, 8(6). Retrieved July 12,

2005, from http://www.uwsa.edu/ttt/articles/sands2.htm. . Singh, H., & Reed, C. (2001). A white paper: Achieving success with blended learning. Centra

Software. Retrieved July 12, 2005, from http://www.centra.com/download/

whitepapers/blendedlearning.pdf. Smelser, L. M. (2002, March 20-23). Making connections in our classrooms: Online and off Paper

presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and

Communication, Chicago. Thomson, I. (2002). Thomson job impact study: The next generation of corporate learning. Retrieved

July 7, 2003, from http://www.netg.com/DemosAndDownloads/Downloads/

JobImpact.pdf. U.S. Department of Education. (2001). The condition of education 2001. Washington, DC:

National Center for Educational Statistics. Waddoups, G., & Howell, S. (2002). Bringing online learning to campus: The hybridization

of teaching and learning at Brigham Young University. International Review of Research in

Open and Distance Learning, 2(2). Retrieved July 12, 2005, from http://www.irrodl.org/

content/v2.2 /waddoups.html.

CHAPTER TWO

THE BLENDED LEARNING IMPERATIVE

Elliott Masie

All learning is blended learning! That is a bold statement and reflects our view of the definition of blended learning: the use of two or more styles of content or context delivery or discovery.

In 1998, the training field popularized the term blended learning to refer to the mixture of e-learning and classroom learning. Many people started to use it as a way of addressing what they perceived to be the structural weaknesses of e-learning at that time, mainly in its limited ability to foster interaction, context, and remediation.

However, blended learning has always been a major part of the landscape of training, learning, and instruction. Think back to your best class in college. The faculty member often used a pedagogical approach that might have included:

22

Formal lectures

Classroom discussion

Homework or reading assignments

Development of papers

Group projects

Assessments or exams

One-to-one coaching during office hours

The Blended Learning Imperative

23

In addition, the learners made the blend even richer with the following strategies:

Conversations between peers

Sharing notes

Study sessions

Library research

Checking with former students about exams or grading models

Why all of these elements? Because as complex beings, we don't learn in a simple or uniform fashion. Even when all learning seems to be confined to a single delivery system, such as a classroom or an online class, learners often break out of those confines and independently enrich the material.

Reasons for Creating Blended Learning

Learners and their teachers and trainers have always created overt or covert blended learning for many compelling reasons. We look at seven of them.

Multiple Perspectives on Content

Learners are a varied group of individuals and have a varied set of learning styles. They seem to achieve higher mastery of content when they can take multiple passes through the material and deal with it through different learning processes.

Cognitive Rehearsal

David and Roger Johnson, pioneers of collaborative education in the K-12 space, termed the phrase cognitive rehearsal to refer to the process by which learners master newly presented material by talking about the content (Johnson & Johnson, 1985). For example, a colleague comes back from a management class and talks to her spouse or cubicle mate about the newly acquired content. Ironically, the value of this conversation is often richer for the speaker than the listener. Johnson and Johnson have often referred to this as "hearing the content for the second time from your own lips." We see this often in the e-learning world as learners push back from their terminals and start to discuss the screen-based material with a neighbor.

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Context Is Often More Important Than Content

I am a strong proponent of the vital need to raise the status of and recognition for context. It is easy to author and deliver content. Most e-learning is filled with organizationally approved content. Yet learners have an incredible thirst and instructional need for context, the unofficial and peer-validated view of the authored content. The classroom instructor delivers the content as reflected in the PowerPoint slides or courseware. Then she takes a few steps to the right or left of the podium and tells the story about how the content is really being implemented, and that is what people remember. One of the key values that face-to-face or other interactions have in the blended learning model is the ability to add context.

Value Sorting Is Core to Blended Learning

One of the behaviors that the learner is always struggling through is their need to sort the content by value. There are three general sorting categories:

High-value stuff: The content and context that I need to remember, even memorize. It is what I take away from this learning activity.

Medium-value stuff: The content and context that I might need to use at some future date. I will become familiar with it but won't memorize it. I know how to get to it when and if I need it.

No-value stuff: The content that I don't need and won't bother to learn or think about.

Blended learning provides a richer environment for learners to make these decisions. In fact, instructional designers often are in denial about this core sorting process and naively believe that all content is equally important. One of the prime drivers from the learner point of view toward blended learning is the need to reduce and target learning objectives and activities. Multiple processes and models increase the learner's ability to sort.

Learning Is Longitudinal

Much of the dialogue about e-learning has been about the acceleration and compression of learning time. A clear benefit of e-learning can be to accelerate the access of a learner to knowledge. Yet sometimes we have to accept that learning is accomplished over time. The blended learning model fits nicely into this longitudinal view of knowledge acquisition. A learner will learn computer security techniques over a period of weeks or months, mixing formal and informal bursts of training. What we have to work on is to make our assessment and evaluation

The Blended Learning Imperative

25

processes more aligned to longitudinal learning. Let's move beyond testing for competency at the end of a short module. Why not shift the assessment to a more object-based and over-time paradigm?

i Learning Is Social

As humans, we thrive on social experiences, and learning is one of those very primal social experiences. Yet the role of a student is often structured to be quite unsocial. We often see the student as a passive viewer of slides, listener of lectures, screen and mouse clicker, or quiet taker of evaluations. Blended learning recognizes and aligns with the social dimensions of learning.

Learning Is Often Tacit and Unstructured

Some of the most powerful training experiences are often unconventional and not in the common tool kit of an instructional designer. Consider a lunch conversation. A new manager wHl probably get more value and learning from a targeted invitation to have lunch with a senior mentor than from several hours in a class or several modules in an e-learning course. When we expand our thinking about blended learning, we recognize that these experiences are a big piece of the mix. We can take a great online course and add invitations to lunch, tours of the factory, open structured online searches, and other nontraditional elements to supercharge the learning.

Conclusion

I started to use the phrase "magic is in the mix" when blended learning became popular as a term in the 1990s. The magic is the power of adding two or more learning elements. Learners have always known this. They have been blended learning for thousands of years. They add what is missing, they mix it with what they need, and they subtract what is not valuable. They socialize it. They find context. And they transform training and instruction into learning.

Our imperative is to accept and embrace blended learning. We can even stop using the word blended just as we can stop using the letter e in e-learning. Great learning is blended. And learning in the 2000s will always have an element of e.

We have to change much to move toward accepting and leveraging blended learning. The imperative must be embraced by:

Instructional designers, who must expand their models and templates to include blended learning.

Learning and training organizations, which must encourage blended learning through their marketing and charge-back models.

26

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Technology and system suppliers, who must develop authoring tools, learning systems, and content collections to allow blended learning in a rapid development era.

Learners, who must continue to see blended learning as a natural aspect of what they do and not an extender of training time.

Blended learning is an imperative. It reflects the blended nature of our world, our workforce, and the natural process of how people really learn.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1985). Classroom conflict: Controversy versus debate in \ learning groups. American Educational Research Journal, 22(2), 237-256.

Learning Is If

CHAPTER THREE

WHY BLENDED LEARNING HASN'T (YET) FULFILLED ITS PROMISES

Answers to Those Questions That Keep You Up at Night

Jennifer Hofmann

I am a product of Public Television. As a clrild, my hours of daytime television were limited to the line-up on local channel 13. Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood taught me about how to interact and "play nice." Sesame Street introduced counting, the alphabet, and how to identify commonality among objects. ("One of these things is not like the other . . .")

The Electric Company opened up the world of multiplication tables and grammar. Whenever I think of the silent letter E, I recall that words are indeed more powerful than a locomotive.

On Saturday mornings I was fixated not on the cartoons depicting super-heroes and talking animals but on the enchanting series Schoolhouse Rock!. Those wonderful five-minute videos explained the U.S. Constitution, the line-up of the planets in the solar system, and the difference between verbs and adjectives.

I could read just about anything by the age of five. What was missing was reading comprehension. The meaning of the words eluded me. To master that advanced skill, I needed to be exposed to those more expert than I: parents, teachers, and older children. Aha! My first (successful) blended learning experience.

Is it any wonder that I embrace the concept of alternative learning technologies? I instinctively knew the value before I was even a teenager. As an adult, however, the results have been far less satisfying.

27

28

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Why Is Blended Learning the Current Trend?

Those of us who have been in the training profession for any length of time know that there are always trends and fads. We've been introduced to learning organizations, lifelong learning, matrixed teams, learning communities, and a myriad other concepts. Although these practices all have true merit, it takes quite a bit of effort to implement the requisite changes. Worse still, such ideas are often just introduced at the conceptual level and forgotten about at the next reorganization or management change.

So why is blended learning a true shift in our profession instead of a passing fad? In part, it makes significant economic sense that even the bean counters can see immediately. Blended learning also makes sense due to the emergence of geographically dispersed work environments in which staffing levels are constantly being changed. While one part of an organization is being downsized, requiring fewer people to accomplish more work, another part of the organization is growing and hiring.

Gone are the days when we could start all new employees at the same time and conduct two-day orientation programs. Flying instructors and participants around to attend training classes is not economical and is often disruptive to business and personal relationships. Unlike old training models and expectations, we need our training now! Not a month ago, when we didn't have the need for it; not in two weeks, after we have been struggling and making up ways of getting our work done. Now! There is a true need for just-in-time training.

Traditional classroom approaches are not very flexible, and they are expensive. We often wait until we can fill a class before we teach it and hope that the need for the classroom coincides with one being available. The blended learning experience, incorporating synchronous (or live and online) classrooms, makes it cost-effective to train small groups or even provide one-on-one coaching. And these blended classes can be offered more frequently without incurring a lot of extra costs, so a participant who cannot attend a training session on Tuesday or is called away because of an emergency can simply enroll in the next offering.

Since blended learning can have a positive effect the bottom line and can theoretically increase the skills and knowledge of the entire organization, management tends to support and, more important, persist in supporting this shift to nontraditional delivery methods.

A Chronology of Learning Delivery Technologies

For decades, training professionals have had a wide menu of learning technologies from which to choose. Historically, the opportunity to pick and choose from different delivery technologies has been around since at least the 1800s. In

Why Blended Learning Hasn't (Yet) Fulfilled Its Promises

29

addition to the traditional Socratic and Didactic classroom models, educators have had access to a wide variety of tools that were cutting edge when they were introduced:

1450—-Johannes Gutenberg introduces the first Western printing press

1840—First correspondence study (a secretarial program focused on teaching shorthand)

1900s—Audio recordings

1920s—Radio stations

1930s—Television

1960s—Satellite

1960s—Pre—World Wide Web Internet (text-based databases and discussion boards)

1980s—Fiber optic, audiovisual tech/CD-ROM

1990s to the present—World Wide Web

There was great excitement with the introduction of each of these technologies. We educators and trainers kept thinking that the nut was finally cracked and had discovered the best and most efficient way for people to learn.

Edison, with his invention of the moving picture, predicted that we would eventually never need to attend a class again; we would just need to attend recorded lectures of experts in order to become educated. Sound familiar? We (the training profession) have jumped on similar bandwagons with the introduction of every delivery technology since. Somehow we are still using traditional methods as much as ever before.

Imaginative educators, with the assistance of technical experts, have found ways to exploit and combine (or blend) these technologies to meet their learning objectives.

Where We Are Today?

New conventional wisdom and years of academic research tell us that the best programs are a blend of learning technologies. Blending technologies that take advantage of learning styles, learner convenience, and the best practices of instructional design enable course developers to create programs that engage the learner and maximize learning retention. For this reason, mixing the best blend of learning technologies is a critical success factor in creating effective learning of

30

The Handbook of Blended Learning

any kind. And the new online learning technologies are so varied, widely available, and relatively inexpensive that creating this type of effective learning experience is something that almost any content development team can do.

And that's great—except (and this probably won't surprise many of you) it hasn't been working. Of course, this is a generalization. You can turn to many chapters in this book to find examples of successfully blended initiatives that met or exceeded expectations, and we can learn from every one of them. Still, most organizations have yet to break the code and create a successful truly blended experience.

So What's the Problem, Really?

We have identified the need for a blended solution; we have technology that can support a wide variety of designs and delivery methods; we have experts who can create the content; and organizations have budgets supporting the design and development of such programs. So what's the problem with this underwhelming return on investment and expectations on a seemingly-can't-lose scenario?

Actually, there are issues that have historically created roadblocks for blended learning initiatives. These are at the heart of why blended learning has not yet fulfilled its promise of being the best way to deliver information since Gutenberg invented the printing press:

Designing Blended Learning Experiences

Creating programs without using a formal design process

Assuming that redesigning an existing program is easier than starting from scratch

Stringing together stand-alone components into a learning path instead of truly weaving learning experiences together

Facilitating Blended Learning Experiences

Overemphasizing the live components and undervaluing the self-directed components of the blend

Lack of experience on the part of the training team in facilitating the blend

No formal training for the implementation team

Supporting Blended Learning Experiences

Lack of organizational understanding, and therefore support for blended programs

Inexperienced learners who have not been taught how to learn online

Why Blended Learning Hasn't (Yet) Fulfilled Its Promises 31

In the rest of this chapter, I address these issues and others, and provide answers to those burning questions that are keeping you up at night.

Designing Blended Learning Experiences

During my early days as a training professional, I employed, I admit, techniques that were less than structured. I worked in financial services and delivered custom software training to medical professionals. Back then I designed programs by talking with the subject matter expert (SME) and "designing" on my best instinct, generally with a positive result. Then my team was told we would be trained to be instructional designers, and we rebelled. How dare they tell us we need to be trained on a function we had been performing well until then?

Twelve years, multiple workshops, and a master's degree in instructional technology later, and now I am not only a convert but an evangelist. So as a card-carrying, blue-blooded instructional designer, I'll tell you that any type of program, from a one-hour "lunch and learn" to a five-day "boot camp," should be formally designed. I'll tell you that, but realistically I know that doesn't happen.

Experienced designers (cum trainers) often know their audiences and content so thoroughly that they can create effective presentations and training interventions with minimal design actually written down on paper. That is not to say that programs are not designed, just that the experienced team always needs to identify subordinate skill objectives and domains of learning formally. Pilots are informal, if they occur at all. Programs can be rapidly created and deployed. When a skilled trainer identifies design gaps by looking at confused or bored faces or interpreting negative body language, the design is modified on the fly, and can often go unnoticed by the audience.

We simply cannot get away with this practice when creating a blended learning experience. Lack of a formal instructional design process is much more obvious in a nontraditional environment. Even worse, the participants are most often aware of the issues before the blended learning facilitator. Without the immediate opportunity for eye contact, body language, or (in self-directed formats) verbal feedback, we cannot easily ascertain if a participant understands instructions or content. As a result, participants often leave these programs confused, unsatisfied, and, worst of all, without the training they need. And we may never know it.

I follow the same instructional systems design (ISD) process I was taught over a decade ago. That happens to be the Dick and Carey model (Dick, Carey, & Carey, 2004). (There are others that are just as legitimate.) This ISD process suggests the following process for the creation of any training intervention.

32

The Handbook of Blended Learning

Stages of Instructional Systems Design

Identification of instructional goals

Subordinate skill analysis

Learner and context analysis

Construction of performance objectives

Identification of assessment techniques

Identification of instructional strategies

Determination of appropriate delivery media

Course development

Evaluation

The key here is Step 7: determination of appropriate delivery media. Most of us find this to be quite unusual. We are accustomed to starting a project already knowing what the delivery medium will be. ISD tells us that just about everything is done before you determine what tools will be used to deliver the content.

In a world where our clients/managers/sponsors come to us and say that they need a four-hour Web-based course on how to package cheese effectively, this process seems unrealistic. We talk to our experts, we look at our resources, and we build our courses based on the client's stated specifications. With the time lines and budgets available to us, this seems to be the most expeditious solution.

If we had the time for a formal ISD process, we might often discover that the delivery method requested by the client was not at all appropriate for the audience, content, technology, or budget. This is perhaps the most important argument in favor of formal design. Going down the wrong delivery path results in less-than-optimal learning results and can eventually lead to an undertrained workforce, a drained development budget, and a lack of confidence in the training team.

How Do We Design the Blend?

The most common instructional design question I am asked when discussing blending learning technologies is, "What can be taught online?" Of course, there are some subjects that just don't seem to lend themselves to an online approach. But you don't know what these subjects are until you go though the instructional design process.

Do not restrict your options by looking at an entire subject (or goal). Look at each individual objective. Understanding your objectives gives you the flexibility to determine the best way to deliver each component.

Why Blended Learning Hasn't (Yet) Fulfilled Its Promises 33

Here are a few things to keep in mind when considering your blend:

Some objectives may be best taught in a traditional classroom, like completing technical lab work. Think of those kinesthetic task-based objectives that can result in disastrous outcomes when not performed well. (I still want my future brain surgeon to practice on real people with a seasoned doctor nearby.)