- •Министерство образования российской федерации

- •Все многочисленные опечатки и ошибки сохранены

- •The Infinitive

- •Формы причастия

- •Introduction

- •The parts of a computer system

- •Input Devices

- •The development of computers

- •Integrated circuits

- •Instruction codes

- •Men and Machines before Babbage

- •The Basic Action of a Computer

- •Programming languages

- •Инфинитивные обороты

- •Маркеры

- •Why Assembly Language?

- •Structured Programming

- •Степени сравнения прилагательных.

- •Interactive processing

- •Unit 5 Функции слова that

- •Перевод терминологических словосочетаний (тс)

- •The operating system

- •Defining of microcomputers

- •Classes of computers

- •Pc Software: yesterday, today and tomorrow

- •8087 Architecture

- •If I were you I would attend the lecture. На твоем месте я бы посетил лекцию.

- •Употребление слова one

- •Real Numbers

- •Герундиальный оборот

- •Special Values

- •Абсолютный причастный оборот

- •Data Format Conversion

- •Considerations For selecting a dsp Processor

- •Introduction

- •I/o Handling Capabilities

- •Parallel and Serial Communications

- •Функции слова it.

- •Evolution of the microprocessors

- •Break the 486 speed barrier

- •80486 Mainboard

- •What is the difference between 386sx, 386dx, 486sx, and 486dx processors?

- •Differences between processors

- •General Setup Notes

- •Ethernet Versus Token Ring

- •The 10base-t Revolution

- •Internet, Networking, and Distributed Services

- •The JavaScript Language

- •Networking Objects with corba

- •Implementing Component Objects

- •Приложение 1. Список союзов, наречий и составных предлогов

- •Приложение 2. Vocabulary

- •Приложение 3. Answers to the crossword

- •Маргарита Петровна Милич программирование, компьютеры, сети

Instruction codes

Instructions for the processor are stored in memory. Such instructions must also be represented as patterns of bits. The manufacturer of the computer specifies a code for each instruction. These patterns could be typical instruction codes for a computer.

Binary Numbering

Computer gets all program instructions and data from its memory. Memory is comprised of integrated circuits (or "chips") that contain thousands of electrical components. Like light switches, these components have only two possible settings: "On" or "Off". Still, with only these two settings, combination of memory components can represent numbers of any size. How? Read on.

The On and Off settings of a memory component correspond to the two digits of the binary numbering system, the fundamental system for

computers. Having only two digits. 1 (On) and 0 (Off), the binary numbering system is a base 2 system. Again, it differs from the standard decimal numbering system, which has 10 digits (0 through 9).

The switch-like components of memory are called "bits", short for binary digits. By convention, a bit that is On has the value 1 and a bit that, is Off has the value 0. This appears to be woefully limiting, until you consider that a decimal digit (no, it is not called a "det") can range only from 0 to 9. Just as you can combine decimal digits to form numbers larger than 9, you can combine binary digits to form numbers larger than 1.

As you know, to represent a decimal number larger than 9 requires an additional "tens position" digit. Likewise, to represent a decimal number larger than 99 requires a "hundred position" digit, and so on. Each decimal digit you add has a weight of 10 times the digit to its immediate right.

For example, you can represent the decimal number 324 as 3 • 100 + 2 • 10 + 4 or as 3 • 102 + 2 • 101 + 4 • 100. Thus, each decimal digit is a power of 10 greater than the preceding digit.

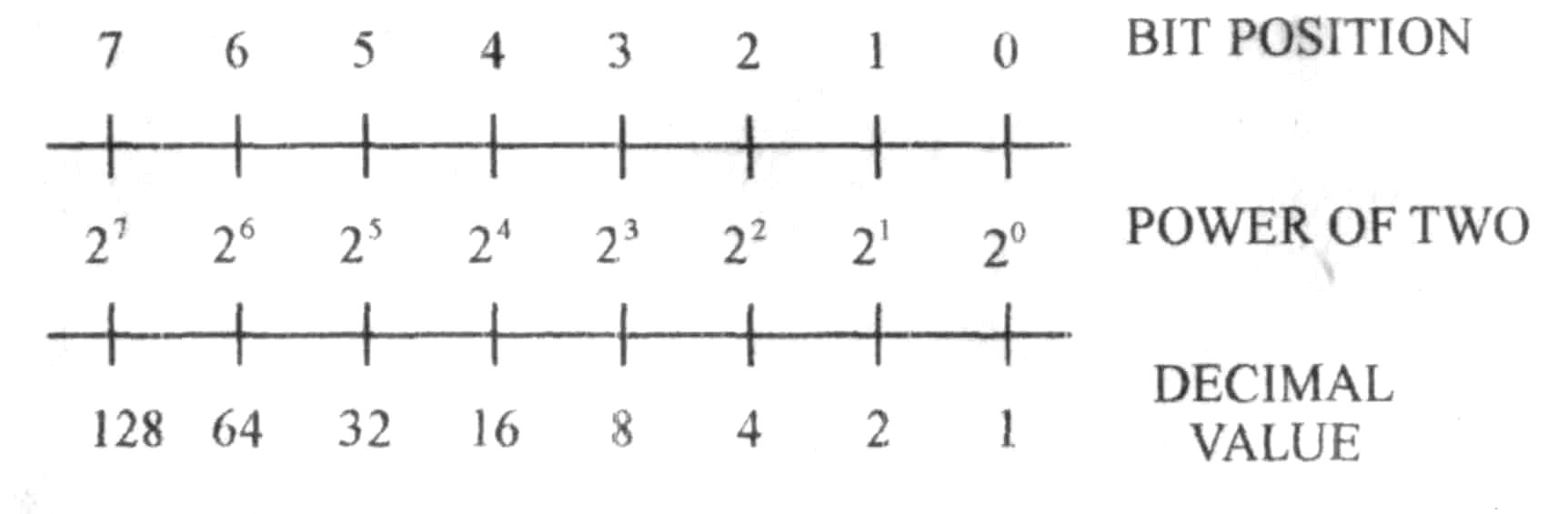

A similar rule applies to the binary numbering system. Here, each binary digit is a power of two greater than the preceding digit. The rightmost bit has a weight of 20 (decimal 1), the next bit has a weight of 21 (decimal 2), and so on.

So to find the value of any given bit position, you double the weight, of the preceding bit position. Thus, the binary weights of the first eight bits are 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128.

Fig. 3. Binary numbering.

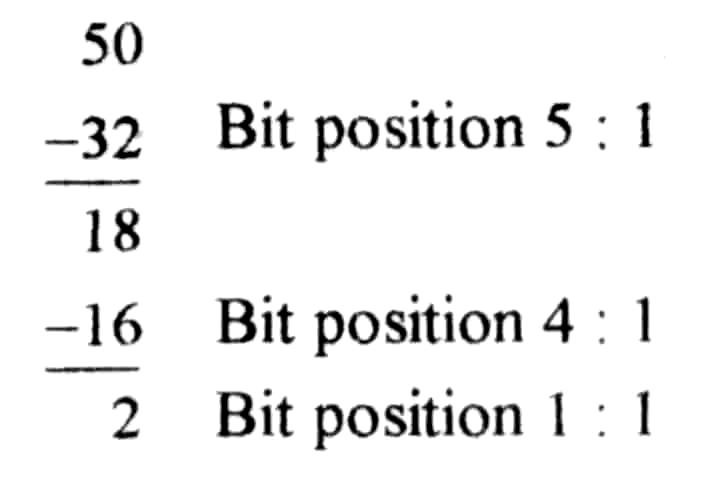

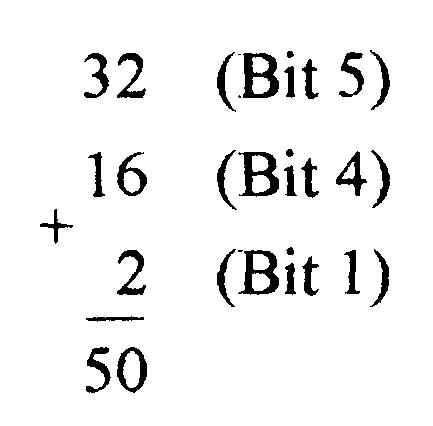

To convert a decimal value to binary, you make a series of simple subtractions. Each subtraction produces the value of a single binary digit (bit).

To begin, subtract the largest possible binary weight from the decimal value and enter a 1 in that bit position. Then subtract the next largest possible binary weight from the result and enter a 1 in that bit position. Continue until the result is zero. Enter a 0 in any bit position whose weight cannot be subtracted from the current decimal value. For example, to convert decimal 50 to binary:

VI. Попроси на повторение. Ответьте на вопросы как можно полнее.

What is a computer?

What is it used for?

What parts does a computer consist of?

What is the CPU made up of?

What does a computer hardware include?

What kinds of operations does a modern computer perform?

What is needed for the computer system to operate?

According to what features are computers divided into generations?

How many computer generations are known to you at present?

In what form is data represented within a computer system?

What is the smallest unit of data?

What is the commonly used code?

4. Прочитайте текст, озаглавьте его и разбейте на абзацы

In 1830, Charles Babbage, while a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University, licked the problem (разрешил задачу) of carrying, and tried to build an automatic calculator before a practical adding machine was introduced. Babbage proposed a punched card calculator using decimal counting wheels capable of completing an addition operation in one second. It was to be largely automatic and not dependent upon operator action. He realized he would sacrifice (жертвовать) speed if the machine had to stop after every operation and wait for the operator to enter the next batch of data. Therefore, to achieve speed, he had to accelerate the entry of data, as well as computing time. He tried to build into his device the function of the work sheet, which is to store data until it is ready to be acted upon, and the function of the operator who enters the data. Data had to be stored in a form that could be entered rapidly and mechanically into the machine. To accomplish this, the machine was divided into three parts: the store, the mill, and the control. The store was to be the part which held all the data to be used during the course of a long computation. The mill would operate on the data and the control became the automatic operator. The data in the store was arranged (располагать) in an orderly fashion ready to be transferred to the mill when needed. The mill contained the arithmetic unit. When the mill finished each computation, the control would bring more information from the store. Babbage soon realized that having data stored and available did not make his machine automatic. The machine had to know whether to add, subtract, multiply, or divide. Babbage realized that he had to have an instruction store as well as data store. He planned them as separate memories. Babbage planned to have all of the instructions required for a long series of operations prepared in advance (заранее) and placed in the instruction store. They would be placed in the order in which they were to be performed. Whenever his mill finished one operation, it would ask for the next one from the instruction store.

Прочитав текст, дайте значения следующим словам. Каким современным аналогам они соответствуют?

the store, the mill, the control

5. Прочитайте следующие тексты и ответьте па вопросы. Старайтесь читать как можно быстрее.

What operations did the first calculating machines perform?

Whose machine was the most advanced?

What important principles of the machines discussed were used in later mechanical calculators?