- •The classification of speech sounds The English Vowels

- •Use of vowels in languages

- •Monophthongs, diphthongs, triphthongs

- •Differences in the articulation bases of english and ukrainian vowels

- •Peculiarities of english vowels

- •Recommended Literature on the topic:

- •Workshop on lecture 4

- •The classification of speech sounds

- •The English Vowels

- •Vowel phonemes. Description of principal variants

- •Subsidiary variants of english vowel phonemes

- •Diphthongs

Monophthongs, diphthongs, triphthongs

A vowel sound whose quality doesn't change over the duration of the vowel is called a monophthong. Monophthongs are sometimes called "pure" or "stable" vowels. A vowel sound that glides from one quality to another is called a diphthong, and a vowel sound that glides successively through three qualities is a triphthong. All languages have monophthongs and many languages have diphthongs, but triphthongs or vowel sounds with even more target qualities are relatively rare cross-linguistically. English has all three types: the vowel sound in hit is a monophthong [ɪ], the vowel sound in boy is in most dialects a diphthong [ɔɪ], and the vowel sounds of, flower (BrE [aʊə] AmE [aʊɚ]) form a triphthong (disyllabic in the latter cases), although the particular qualities vary by dialect.

In phonology, diphthongs and triphthongs are distinguished from sequences of monophthongs by whether the vowel sound may be analyzed into different phonemes or not. For example, the vowel sounds in a two-syllable pronunciation of the word flower (BrE [flaʊə] AmE [flaʊɚ]) phonetically form a disyllabic triphthong, but are phonologically a sequence of a diphthong (represented by the letters <ow>) and a monophthong (represented by the letters <er>). Some linguists use the terms diphthong and triphthong only in this phonemic sense. From the articulatory point of view an English diphthong is an indivisible phonetic whole. It is necessary to give different definitions by different scholars. It is important to pay attention to the position of the tongue while pronouncing the nuclei of the diphthong, which can be the reason for many mistakes. It is necessary to think over the causes of mistakes and ways of eliminating them.

Vowels are the class of sound which makes the least obstruction to the flow of air. They are almost always found at the centre of a syllable, and it is rare to find any sound other than a vowel which is able to stand alone as a whole syllable. In phonetic terms, each vowel has a number of properties that distinguish it from other vowels. These include the shape of the lips, which may be rounded (as for an [ u ] vowel), neutral (as for ([e]) or spread (as in a smile, or an [ i ] vowel – photographers traditionally ask their subjects to say "cheese" / tʃi:z / so that they will seem to be smiling). Secondly, the front, the middle or the back of the tongue may be raised, giving different vowel qualities: the BBC English / a / vowel ('cat') is a front vowel, while the / a: / of 'cart' is a back vowel. The tongue (and the lower jaw) may be raised close to the roof of the mouth, or the tongue may be left low in the mouth with the jaw comparatively open. In British phonetics we talk about 'close' and 'open' vowels, whereas American phoneticians more often talk about 'high' and 'low' vowels. The meaning is clear in either case.

Vowels also differ in other ways: they may be nasalised by being pronounced with the soft palate lowered as for [ n ] or [ m ] – this effect is phonemically contrastive in French, where we find "minimal pairs" such as très / trÈ / ("very") and 'train' / trÈ / ("train"), where the /`/ diacritic indicates nasality. Nasalised vowels are found frequently in English, usually close to nasal consonants: a word like 'morning' / mɔ:niŋ / is likely to have at least partially nasalised vowels throughout the whole word, since the soft palate must be lowered for each of the consonants. Vowels may be voiced, as the great majority are, or voiceless, as happens in some languages, unstressed vowels in the last syllable of a word are often voiceless and in English the first vowel in 'perhaps' or 'potato' is often voiceless. It is claimed that in some languages (probably including English) there is a distinction to be made between tense and lax vowels, the former being made with greater force than the latter. In phonetics, a vowel is a sound in spoken language, such as English ah! [ɑː] or oh! [oʊ], pronounced with an open vocal tract so that there is no build-up of air pressure at any point above the glottis. This contrasts with consonants, such as English sh! [ʃː], where there is a constriction or closure at some point along the vocal tract. A vowel is also understood to be syllabic: an equivalent open but non-syllabic sound is called a semivowel. In all languages, vowels form the nucleus or peak of syllables, whereas consonants form the onset and (in languages which have them) coda. However, some languages also allow other sounds to form the nucleus of a syllable, such as the syllabic l in the English word table [ˈteɪ.bl̩] (the stroke under the l indicates that it is syllabic; the dot separates syllables).

We might note the conflict between the phonetic definition of 'vowel' (a sound produced with no constriction in the vocal tract) and the phonological definition (a sound that forms the peak of a syllable). The approximants [j] and [w] illustrate this conflict: both are produced without much of a constriction in the vocal tract (so phonetically they seem to be vowel-like), but they occur on the edge of syllables, such as at the beginning of the English words 'yes' and 'wet' (which suggests that phonologically they are consonants). The American linguist Kenneth Pike suggested the terms 'vocoid' for a phonetic vowel and 'vowel' for a phonological vowel, so using this terminology, [j] and [w] are classified as vocoids but not vowels. The word vowel comes from the Latin word vocalis, meaning "speaking", because in most languages words and thus speech are not possible without vowels. Vowel is commonly used to mean both vowel sounds and the written symbols that represent them.

Where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a rounded vowel. Vowel length is indicated by appending ː

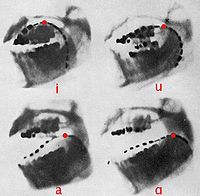

Fig. 1. X-rays of Daniel Jones' [i, u, a, ɑ].

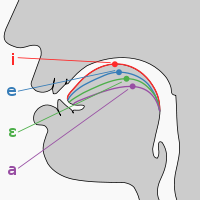

The articulatory features that distinguish different vowel sounds are said to determine the vowel's quality. Daniel Jones developed the cardinal vowel system to describe vowels in terms of the common features height (vertical dimension), backness (horizontal dimension) and roundedness (lip position). These three parameters are indicated in the schematic IPA vowel diagram on the right. There are however still more possible features of vowel quality, such as the velum position (nasality), type of vocal fold vibration (phonation), and tongue root position.

Vowel height is named for the vertical position of the tongue relative to either the roof of the mouth or the aperture of the jaw. In high vowels, such as [i] and [u], the tongue is positioned high in the mouth, whereas in low vowels, such as [a], the tongue is positioned low in the mouth. The IPA prefers the terms close vowel and open vowel, respectively, which describes the jaw as being relatively open or closed. However, vowel height is an acoustic rather than articulatory quality, and is defined today not in terms of tongue height, or jaw openness, but according to the relative frequency of the first formant (F1). The higher the F1 value, the lower (more open) the vowel; height is thus inversely correlated to F1.

The International Phonetic Alphabet identifies seven different vowel heights:

close vowel (high vowel)

near-close vowel

close-mid vowel

mid vowel

open-mid vowel

near-open vowel

open vowel (low vowel)

True mid vowels do not contrast with both close-mid and open-mid in any language, and the letters [e ø ɤ o] are typically used for either close-mid or mid vowels.

Although English contrasts all six contrasting heights in its vowels, these are interdependent with differences in backness, and many are parts of diphthongs. It appears that some varieties of German have five contrasting vowel heights independently of length or other parameters. The Bavarian dialect of Amstetten has thirteen long vowels, reported to distinguish four heights (close, close-mid, mid, and near-open) each among the front unrounded, front rounded, and back rounded vowels, plus an open central vowel: /i e ɛ̝ æ̝/, /y ø œ̝ ɶ̝/, /u o ɔ̝ ɒ̝/, /a/. Otherwise, the usual limit on the number of contrasting vowel heights is four.

The parameter of vowel height appears to be the primary feature of vowels cross-linguistically in that all languages use height contrastively. No other parameter, such as front-back or rounded-unrounded (see below), is used in all languages. Some languages have vertical vowel systems in which, at least at a phonemic level, only height is used to distinguish vowels.

Tongue positions of cardinal front vowels with highest point indicated. The position of the highest point is used to determine vowel height and backness. Vowel backness is named for the position of the tongue during the articulation of a vowel relative to the back of the mouth. In front vowels, such as [i], the tongue is positioned forward in the mouth, whereas in back vowels, such as [u], the tongue is positioned towards the back of the mouth. However, vowels are defined as back or front not according to actual articulation, but according to the relative frequency of the second formant (F2). The higher the F2 value, the fronter the vowel; backness is thus inversely correlated to F2.

The International Phonetic Alphabet identifies five different degrees of vowel backness:

front vowel

near-front vowel

central vowel

near-back vowel

back vowel

Although English has vowels at all five degrees of backness, there is no known language that distinguishes all five without additional differences in height or rounding.

Roundedness refers to whether the lips are rounded or not. In most languages, roundedness is a reinforcing feature of mid to high back vowels, and is not distinctive. Usually the higher a back vowel is, the more intense the rounding.

Different kinds of labialization are also possible. In mid to high rounded back vowels the lips are generally protruded ("pursed") outward, a phenomenon known as exolabial rounding because the insides of the lips are visible, whereas in mid to high rounded front vowels the lips are generally "compressed", with the margins of the lips pulled in and drawn towards each other, a phenomenon known as endolabial rounding. In many phonetic treatments, both are considered types of rounding, but some phoneticians do not believe that these are subsets of a single phenomenon of rounding, and prefer instead the three independent terms rounded (exolabial), compressed (endolabial), and spread (unrounded).

Nasalization refers to whether some of the air escapes through the nose. In nasal vowels, the velum is lowered, and some air travels through the nasal cavity as well as the mouth. An oral vowel is a vowel in which all air escapes through the mouth.

Phonation. Voicing describes whether the vocal cords are vibrating during the articulation of a vowel. Most languages only have voiced vowels, but several Native American languages contrast voiced and devoiced vowels. The combination of phonetic cues (i.e. phonation, tone, stress) is known as register or register complex.

Rhotic vowels or R-colored vowels. Rhotic vowels are the "R-colored vowels" of English and a few other languages.

Tenseness/checked vowels vs. free vowels. Tenseness. Tenseness is used to describe the opposition of tense vowels as in leap, suit vs. lax vowels as in lip, soot. This opposition has traditionally been thought to be a result of greater muscular tension, though phonetic experiments have repeatedly failed to show this. Unlike the other features of vowel quality, tenseness is only applicable to the few languages that have this opposition (mainly Germanic languages, e.g. English. In discourse about the English language, "tense and lax" are often used interchangeably with "long and short", respectively, because the features are concomitant in the common varieties of English. This cannot be applied to all English dialects or other languages. In most Germanic languages, lax vowels can only occur in closed syllables. Therefore, they are also known as checked vowels, whereas the tense vowels are called free vowels since they can occur in any kind of syllable.

The first who tried to describe and classify vowel sounds irrespective of the mother tongue was D. Jones. He devised the system of 8 Cardinal Vowels. This system is an international standard. The basis of the system is physiological. The starting point of the tongue position is for i (the front of the tongue raised as close as possible to the palate).

No. 1 i is equivalent to the French sound of i in si, German sound of ie in Biene.

The gradual lowering of the tongue to the back lowest position gives another point which is easily felt (No. 5 ).

The tongue position between these points was X-rayed and equidistant points were found. For the front position of the tongue they are

No. 1 i mentioned above,

No. 2 e. French sound of e in thé; Scottish pronunciation of, ay in day.

No. 3 ε. French sound of ê in тêте.

No. 4 a. French sound of a in la.

If we compare these four Cardinal Vowels with the Ukrainian vowel system, we may state that:

No. 1 cardinal i is pronounced with the position of the tongue higher than for the Ukrainian accented і in the word міліграм.

No. 2 cardinal e is pronounced with the position of the tongue narrower than the Ukrainian e in the word тесть.

No. 3 is similar to the Ukrainian е in the word етап.

For the back position of the tongue four auditory equidistant points were also established (from the lowest to the highest position of the back part of the tongue). They are:

No. 5 . Nearly what is obtained by taking away the lip-rounding from English sound of о in hot; French vowel a in pas.

No. 6 כ. German sound of о in Sonne.

No. 7 о. French sound of o in rose, Scottish o in rose.

No. 8 u. German sound of и in gut.

There are no sounds similar to Nos 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 in Ukrainian.

In spite of the theoretical significance of the Cardinal Vowel System its practical application is limited to the field where no comparison is needed, in purely scientific work. In language teaching this system can be learned only by oral instruction from a teacher who knows how to pronounce the Cardinal Vowels. Those who have access neither to a qualified teacher, nor to recordings cannot expect to learn the values of these or any other cardinal vowels with accuracy.

Acoustically vowels are musical tones (not noises): the word "vowel" is a derivative of "voice". Acoustically vowels differ due to their tembral coloring, each vowel is characterized by its own formants (that is concentrations of energy in certain frequency regions on the spectrogram).

Phoneticians suggest classifying vowels according to the following principles:

Position of the lips

Position of the tongue

Degree of tenseness and the character of the end of a vowel

Length

Stability of articulation

According to the position of the lips vowels are classified into: (a) rounded, (b) unrounded. The Ukrainian rounded vowels are pronounced with more lip protrusion than the English rounded vowels. The English rounded vowels are: /u – u:, כ – כ:/, the Ukrainian rounded and protruded vowels are: /о, у/.

According to the position of the tongue it is the bulk of the tongue which conditions most of all the production of different vowels. It can move forward and backward, it may be raised and lowered in the mouth cavity. Nowadays scientists divide vowels according to the (a) horizontal and (b) vertical movements of the tongue.

horizontal – When the bulk of the tongue moves backwards, it is usually the back part of the tongue which is raised highest towards the soft palate. Vowels produced with the tongue in this position are called back. They are subdivided into:

fully back: /כ , כ:, u:/, the nuclei of the diphthong /כi/, and the Ukrainian /o, y/

back-advanced: / Λ, υ, :/and the nuclei of the diphthongs /∂υ, υ∂/.

When the bulk of the tongue moves forward, it is usually the front part of the tongue which is raised highest towards the hard palate. Vowels produced with this position of the tongue are called front. They are subdivided into:

fully front: /i:, e, æ/, the nuclei of the diphthongs /ei, ε∂, ai/ and the Ukrainian /i, e/;

front-retracted: /I/ and the nucleus of the diphthong /аυ/.

The term front is not quite correct, because the front vowels are produced by the action of the mouth resonator, which is in the back part of the mouth cavity and the raised front of the tongue.

There is some controversy in the subdivision (and terming) of vowels into front and front-retracted, back and back-advanced (e.g., whether /i:/ & /I/ are different phonemes (sounds different not only in quantity but mainly in quality) or they are variants of one and the same phoneme; the same about /u:/ & /υ/).

Terminological controversy about vowels is only of academic interest because in speech the "cardinal" points mentioned in the diagrams of vowels are slightly altered. The guiding principle in teaching English vowel sounds should be accurate articulatory description accompanied by diagrams and drills.

In the production of mixed, or central, vowels the tongue is raised towards the junction between the hard and the soft palate, e.g., the Ukrainian vowel /a/, Russian /ы/. They are produced neither in the front, nor in the back part of the mouth cavity.

Some British phoneticians consider /∂, з:/ "central". D. Jones says that the central part of the tongue is raised highest and it is culminating at the junction between "front" and "back". He regards /∂, ∂:/ as variants of one phoneme. However, Н. Sweet defines /∂, ∂:/ as "mixed".

Ukrainian & Russian phoneticians also define the vowels /∂, ∂:/ as "mixed", because the tongue position in their production is different from that of the Ukrainian central /а/ or Russian central /ы/.

vertical – According to the vertical movements of the tongue vowels are subdivided into:

high: /i:, I, u, u:/ and /i, у, и/;

mid, half open /e, ∂:, о(u), ε(∂), ∂/ and /e, о/;

low, open: /Λ, כ:, æ, a(i, u), :, כ, כ(i)/ and /a/.

Each of the subclasses is subdivided into vowels of narrow variation and vowels of broad variation:

high |

narrow variation: |

/i:, u:/ and /i, и, у/; |

broad variation: |

/I, u/; |

|

|

|

|

mid |

narrow variation: |

/e, ∂:, o(u)/; |

broad variation: |

/ε(∂), ∂/; |

|

|

|

|

Low |

narrow variation: |

/Λ, כ:/; |

broad variation: |

/:, כ, æ, a(I, u)/ and /a/. |

The Ukrainian /e, о/ are placed on the border of the mid-open vowels of broad and narrow variation.

According to the degree of tenseness traditionally long vowels are defined as tense and short as lax. The term "tense" was introduced by H. Sweet, who stated that the tongue is tense when vowels of narrow variety are articulated. This statement is a confusion of two problems: acoustic and articulatory ones, because "tenseness" is an acoustic notion and should be treated in terms of acoustic data. However, this phenomenon is connected with the articulation of vowels in unaccented syllables (unstressed vocalism). The decrease of tenseness results in the reduction of vowels, that is in an unstressed position they may lose their qualitative characteristics.

When the muscles of the lips, tongue, cheeks and the back walls of the pharynx are tense, the vowels produced can be characterized as "tense". When these organs are relatively relaxed, lax vowels are produced. There are different opinions in referring English vowels to the first or to the second group. Some consider only the long /i:/ and /u:/ to be tense. Some define all long English vowels as tense as well as /æ/.

This problem can be solved accurately only with the help of precise electronic instruments. The Ukrainian vowels are not differentiated according to their tenseness but one and the same vowel is tense in a stressed syllable compared with its tenseness in an unstressed one.

Some phoneticians suggest subdividing vowels according to the character of the end into "checked" and "free". This principle of vowel classifications is not singled out by British and American phoneticians.

When the intensity of the vowel does not diminish towards its end, such vowel is called "checked". When the intensity of the vowel decreases, the vowel is called "free". This problem is closely connected with articulatory transitions in syllable division and should be treated in terms of acoustic properties of vowels on the syllable level.

According to the length vowels are subdivided into: (historically) long and (historically) short.

Vowel length depends on a number of linguistic factors:

position of the vowel in a word,

word accent,

the number of syllables in a word,

the character of the syllabic structure,

sonority.

(1) Positional dependence of length can be illustrated by the following example:

be – bead – bit

we – weed – wit

fee – feed – feet

In the terminal position a vowel is the longest, it shortens before a voiced consonant, it is the shortest before a voiceless consonant.

(2) A vowel is longer in an accented syllable, than in an unaccented one:

forecast n /'fo:ka:st/ – прогноз

to forecast v /fo:'ka:st/ – прогнозувати (погоду)

In the second example /כ:/ is shorter than in the first, though it may be pronounced with /כ:/ equally long.

(3) If we compare a one-syllable word and the word consisting of more than one syllable, we may observe that similar vowels are shorter in a polysyllabic word. Thus in the word verse /∂:/ is longer than in university.

(4) In words with V, CV, CCV type of syllable (open) the vowel length is greater than in words with VC, CVC, CCVC (closed) type of syllable. For example, /∂:/ is longer in err (V type), than in earn (CVC type), /ju:/ is longer in dew (CV type), than in duly (CVCV type).

(5) Vowels of low sonority are longer, than vowels of greater sonority. It is so, because the speaker unconsciously makes more effort to produce greater auditory effect while pronouncing vowels of lower sonority, thus making them longer. For example, /I/ is longer than /כ/, /i:/ is longer than /a:/, etc.

Besides, vowel length depends on the tempo of speech: the higher the rate of speech the shorter the vowels.

Length is a non-phonemic feature in English but it may serve to differentiate the meaning of a word. This can be proved by minimal pairs, e.g.

beat – bit /bi:t – bit/

deed – did /di:d – did/

The English long vowels are /i:, u:, כ:, а:, ∂:/.

The English short vowels are /I, e, æ, כ, Λ, ∂/.

The stability of articulation is the principle of vowel classification which is not singled out by British and American phoneticians. In fact, it is the principle of the stability of the shape, volume and the size of the mouth resonator.

We can speak only of relative stability of the organs of speech, because pronunciation of a sound is a process, and its stability should be treated conventionally.

According to this principle vowels are subdivided into:

monophthongs, or simple vowels,

diphthongoids,

diphthongs, or complex vowels.

English monophthongs are pronounced with the more or less stable lip, tongue and the mouth walls position. They are: /I, e, æ, :, כ, כ:, υ, Λ, ∂:, ∂/.

A diphthongoid is a vowel, which ends in a different element, yet producing neither impression nor effect of a diphthong. There are two diphthongoids in English: /i:, u:/.

Diphthongs are defined differently by different authors. One definition is based on the ability of a vowel to form a syllable. Since in the diphthong only one element serves as a syllabic nucleus, a diphthong is a single sound.

Another definition of a diphthong as a single sound is based on the instability of the second element. The third group of scientists define a diphthong from the accentual point of view: since only one element is accented and the other is unaccented, a diphthong is a single sound.

“unisyllabic gliding sound in the articulation of which the organs of speech start from one position and then glide to the other position.”

“phonemically diphthongs are sounds that cannot be divided morphologically”. E.g. the Ukrainian /ай/ in can be separated: ча-ю.

The first element of a diphthong is the nucleus, the second is the glide. A diphthong can be falling – when the nucleus is stronger than the glide, and rising – when the glide is stronger than the nucleus. When both elements are equal such diphthongs are called level.

English diphthongs are falling with the glide toward:

i – /ei, ai, oi/,

u – /u, ou/,

∂ – /i∂, ε∂, υ∂/

Diphthongs /ei, ou, כi, au, ai/ are called closing, diphthongs /ε∂, i∂, ээ, υ∂/ are called centring, according to the articulatory character of the second element.