- •Lecture 8 old english grammar Plan

- •Literature

- •Preliminary remarks. Form-Building. Parts of Speech and Grammatical Categories

- •The noun Grammatical Categories. The Use of Cases

- •Morphological Classification of Nouns. Declensions

- •The pronoun

- •Personal Pronouns

- •Other Classes of Pronouns

- •The adjective Grammatical Categories

- •Weak and Strong Declension

- •Degrees of Comparison

- •The verb

- •Grammatical Categories of the Finite Verb

- •Grammatical Categories of the Verbals

- •Morphological Classification of Verbs

- •Strong Verbs

- •Weak Verbs

- •Minor Groups of Verbs

- •The Phrase. Noun, Adjective and Verb Patterns

- •Compound and Complex Sentences. Connectives

- •Word Order

Compound and Complex Sentences. Connectives

Compound and complex sentences existed in the English language since the earliest times. Even in the oldest texts we find numerous instances of coordination and subordination and a large inventory of subordinate clauses, subject clauses, object clauses, attributive clauses, adverbial clauses. And yet many constructions – especially in early original prose – look clumsy, loosely connected, disorderly and wanting precision, which is natural in a language whose written form had only begun to grow.

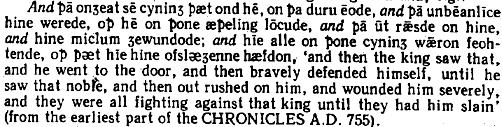

Coordinate clauses were mostly joined by and, a conjunction of a most general meaning, which could connect statements with various semantic relations. The ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLES abound in successions of clauses or sentences all beginning with and, e.g.:

Repetition of connectives at the head of each clause (termed "correlation") was common in complex sentences:

![]()

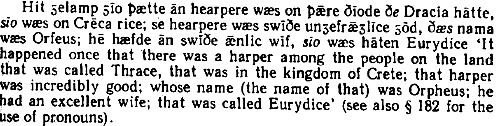

Attributive clauses were joined to the principal clauses by means of various connectives, there being no special class of relative pronouns. The main connective was the indeclinable particle pe employed either alone or together with demonstrative and personal pronouns:

![]()

The pronouns could also be used to join the clauses without the particle pe:

The pronoun and conjunction pæt was used to introduce object clauses and adverbial clauses, alone or with other form-words: oð ð et ‘until’,

er, p em pe ‘before’, p et ‘so that’ as in:

![]()

Some clauses are regarded as intermediate between coordinate and subordinate: they are joined asyndetically and their status is not clear:

127

127

In the course of OE the structure of the complex sentence was considerably improved. Ælfric, the greatest writer of the late 10th – early 11th c., employed a variety of connectives indicating the relations between the clauses with greater clarity and precision.

Word Order

The order of words in the OE sentence was relatively free. The position of words in the sentence was often determined by logical and stylistic factors rather than by grammatical constraints. In the following sentences the word order depends on the order of presentation and emphasis laid by the author on different parts of the communication:

![]()

‘the Finns, it seemed to him, and the Permians spoke almost the same language’ – direct word order.

![]()

![]() ‘many

stories told him (lit. "him told") the Permians either

about their own land or about the lands that were around them’–

the

objects spella,

him are

placed at the beginning; the order of the subject and predicate is

inverted and the attention is focussed on the part of the sentence

which describes the content of the stories.

‘many

stories told him (lit. "him told") the Permians either

about their own land or about the lands that were around them’–

the

objects spella,

him are

placed at the beginning; the order of the subject and predicate is

inverted and the attention is focussed on the part of the sentence

which describes the content of the stories.

Nevertheless the freedom of word order and its seeming independence of grammar should not be overestimated. The order of words could depend on the communicative type of the sentence – question versus statement, on the type of clause, on the presence and place of some secondary parts of the sentence.

Inversion was used for grammatical purposes in questions; full inversion with simple predicates and partial – with compound predicates, containing link-verbs and modal verbs:

![]() ‘From

where do you bring (lit. "bring you") ornamented shields?’

‘From

where do you bring (lit. "bring you") ornamented shields?’

![]() ‘Are you

Esau, my son?’

‘Are you

Esau, my son?’

![]() ‘What

shall I sing?’

‘What

shall I sing?’

If the sentence began with an adverbial modifier, the word order was usually inverted; cf. some common beginnings of yearly entries in the ANGLO-SAXON CHRONICLES:

![]() ‘In this

year came that army to Reading’.

‘In this

year came that army to Reading’.

![]() ‘in this

year went that big army’

‘in this

year went that big army’

with a relatively rare instance of direct word order after hēr.

hēr Cynewulf benam Si ebryht his rices ond Westseaxna wiotan for unryhtum dædum, būton Hāmtūnscīre ‘In this year Cynewulf and the councillors of Wessex deprived Sigebryht of his kingdom for his wicked deeds, except Hampshire (note also the separation of the two coordinate subjects Cynewulf and wiotan).

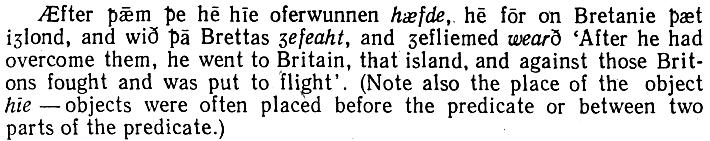

A peculiar type of word order is found in many subordinate and in some coordinate clauses: the clause begins with the subject following the connective, and ends with the predicate or its finite part, all the secondary parts being enclosed between them. Recall the quotation:

![]()

![]()

But the very next sentence in the text shows that in a similar clause the predicate could be placed next to the subject:

![]()

‘He said that he lived on the land to the North of the Atlantic ocean’. In the following passage the predicate is placed in final position both in the subordinate and coordinate clauses:

Those were the main tendencies in OE word order. They cannot be regarded as rigid rules, for there was much variability in syntactic patterns. The quotations given above show that different types of word order could be used in similar syntactical conditions. It appears that in many respects OE syntax was characterised by a wide range of variation and by the co-existence of various, sometimes even opposing, tendencies.