0229836_9011C_jack_koumi_designing_educational_video_and_multimedia_for_op-1

.pdf

214 Picture–word synergy for audiovision and multimedia

The type and extent of scaffolding depends on the ability of the learner in relation to the material; some target audiences need little or no scaffolding and in any case the scaffolding should be withdrawn little by little as learners progress. For more on scaffolding see McLoughlin et al. (2000), van Merriënboer (2001) or Merrill (2002a).

4.47Elucidate: moderate the load, pace and depth, maximize clarity. Do not overload students with too many teaching points or too fast a pace, or too much intellectual depth. The appropriate load, pace and depth depends on the level and prior knowledge of the students (e.g. regarding depth, deal with the specific before the general, especially for children).

Regarding clarity, for example, when you have new terminology to define, leave the definition until it is needed. You might be tempted to define such terms at the outset, when signposting what is coming. Resist the temptation – it is better to find a way of signposting that does not require premature definitions.

4.48Texture: for example, insert occasional light items, vary the format whenever it seems natural to vary the mood, exploit the unique characteristics of audio, that is, tone of voice, sequence, pacing, phrasing, timbre, real-world sounds.

4.49Reinforce: give more than one example of a concept, use comparison and contrast, ensure synergy (as in 4.28 to 4.33) between visuals and commentary.

4.50Consolidation of learning could be achieved through students solving end- of-chapter problems and referring to model answers.

4.51How can narrative coherence be salvaged?

Item 4.14 recommended that the package should allow learners total freedom of random access. In that case, the narrative coherence would disappear. Nevertheless, the above narrative structuring principles would help those learners who do follow the recommended order. For the more adventurous learners who stray from the recommended order, there are various techniques whereby the narrative can be preserved, for example, the contents page (or map) tells students the teacher’s intended structure. More comprehensive strategies for preserving the narrative are discussed by Laurillard et al. (2000). They recommend a series of design features that afford learners the opportunity to maintain a narrative line, including:

•a clear statement of an overall goal – to support generation of a task-related plan

•continual reminders of the goal – to support keeping to the plan

•interactive activities – to provide adaptive feedback on actions; to motivate repeat actions to improve performance

•an editable Notepad – to enable students to articulate their conceptions

•a model answer – as feedback on their conceptions; to motivate reflection on their conceptions

Screenwriting principles for a multimedia package 215

C O M M E N T S

Concerning the statement of the goal and reminders of the goal, these can become more specific as learners progress through the package and become more able to understand the language and what is expected of them. Such progressive disclosure was recommended in Chapter 5. Concerning the Notepad, this can convert the narrative into a collaboration between student and package designer.

A final strategy for preserving narrative structure would be to move away from total learner autonomy by restricting random access. One way to do this would be to discourage students from progressing from chapter to chapter until they make a sizeable attempt at the end-of-chapter consolidation activity (similar to the advice by Laurillard (1998), quoted in item 4.35, to conditionally block access to model answers).

4.52Conclusion. Given all the above, it should be clear that you cannot design a perfect picture–word package with your first draft: you need several draft designs and script discussions. In fact, you will need more than you expect because the programming modifications that are required to implement each draft will rarely produce precisely what you envisaged.

Recommendations for future research and design development

Two types of research papers were outlined at the beginning of this chapter. One type reported on experimental studies of individual audio and visual variables. The other type, by UK Open University writers, consisted of summative studies that dealt primarily with macro-level design issues. How do these two sources relate to the above framework of micro-level design guidelines?

The micro - level guidelines in relation to summative, macro - level studies

The guidelines could add flesh to the further development of the overarching issues espoused in the macro-level papers by Laurillard, Taylor and others. In return, such issues need to be borne in mind for future development of design guidelines.

The micro - level guidelines in relation to experimental studies

The guidelines derive from practitioners. They are more detailed than the levels of investigation carried out in the aforementioned experimental studies. This discordance is natural. The variables that can be investigated using a scientifically

216 Picture–word synergy for audiovision and multimedia

acceptable experimental study are simpler than the complex integration of design principles that must be used by practitioners.

On the other hand, these design principles are intuitive and have not been studied scientifically. The framework of design guidelines is offered as a fledgling design theory for researchers to investigate the practitioners’ intuitions. It would be heartening if this chapter could start an iterative process whereby researchers and practitioners collaborate to improve the design of multimedia packages.

Currently, it appears that there is no widespread collaboration between practitioners and researchers. Instead, the aforementioned experimental studies build on theoretical interpretations of previous experiments, such as those compiled by Moreno and Mayer (2000). Based on these results and on various learning theories, the latter authors propose a cognitive theory of multimedia learning that comprises six principles of instructional design:

•split-attention

•modality

•redundancy

•spatial contiguity

•temporal contiguity

•coherence

These six principles exemplify the mismatch between the research literature and the concerns of practitioners.

The split-attention principle was discussed earlier (visual attention detrimentally split between screen text and corresponding diagrams). The principle is intuitively reasonable. Note however that it leads to the either/or recommendation that audio commentary is always superior to screen text. So there is no conception of a judicious combination of the two, as recommended in items 4.15 to 4.24

– namely that screen text should be a judicious précis of the narration, serving as visual mnemonic and an anchor for the narration. This leaves open the danger of splitting visual attention, but with sparse screen text, the effect should not be too detrimental.

The modality principle asserts that

Students learn better when the verbal information is presented auditorily as speech than visually as on-screen text both for concurrent and sequential presentations.

It was noted earlier that Tabbers et al. (2000) reported a counterexample in the case of a complex task that required self-paced reflection of the on-screen text.

Furthermore, note the surprising sequential condition, in addition to the usual concurrent presentation of explanatory text. Moreno and Mayer actually tested the effect of presenting the whole text before the whole animation and also after

Screenwriting principles for a multimedia package 217

the whole animation (and found that audio text was superior in both conditions, as well as when presented concurrently).

The purpose was to determine whether the superiority of audio text was a memory-capacity effect (screen text and diagrams overloading visual working memory) rather than a split-attention effect (insufficient attention paid, in the concurrent presentation, to either or both visual components – screen text and diagrams). They concluded that a memory-capacity effect was at least a contributing factor. Tabbers in his Ph.D. thesis (2002), convincingly contests this explanation, arguing that the split-attention effect alone is sufficient to explain the superiority of audio text. That is, audio text prevents split attention between verbal and pictorial information.

In a later paper, Mayer and Moreno (2003) appear to use the terms modality effect and split attention effect interchangeably (pp. 45, 46), concluding that

the use of narrated animation represents a method for off-loading (or reassigning) some of the processing demands from the visual (processing) channel to the verbal channel.

Putting aside these theoretical controversies, the above extreme manipulation of the variables might possibly help to build a learning theory, but is of little use to the practitioner. Of what use is it to know for sequential presentation that the auditory condition is superior to the visual? If an animation needs to be complemented by audio commentary (true in most cases), there is no point in delaying the commentary rather than synchronizing it. No multimedia designer would contemplate such a design because it would severely limit any synergy between commentary and diagrams.

This leads to a serious point. Creating synergy between diagrams and synchronized audio commentary is not a trivial endeavour. A bad designer could accidentally fabricate a package in which the composition and pacing of the audio commentary actually clashed with the concurrent diagrams, hence interfering with learning. With such a disharmonious design, the dissonance might be reduced by separating the diagrams from the commentary – presenting diagrams and commentary sequentially rather than concurrently. The sequential package would still fail, but not quite as badly. Much better to accept the challenge of creating synergy in a concurrent presentation. Techniques for achieving such synergy are described in items 4.28 to 4.33.

The spatial contiguity principle asserts that

Students learn better when on-screen text and visual materials are physically integrated rather than separated.

This is not surprising, but the mistake of spatially separating text from diagrams is quite common, so the principle is worth stating.

218 Picture–word synergy for audiovision and multimedia

In another sense, the principle is rendered redundant by another finding from the experiment that supported it. It was also found that replacing the on-screen text by audio narration produced even better learning. The authors interpreted this as reconfirming the modality principle – although Tabbers (2002) would presumably argue that a simpler explanation is that visual attention still gets split even when text and diagram are contiguous. In either case, the spatial contiguity principle would be rendered useless, since the recommendation would have to be that on-screen text should be deleted altogether, in favour of audio narration.

However, the authors used text that duplicated the audio rather than being a judicious précis. It was argued above that key words of the audio narration should be presented as on-screen text, thereby reinforcing and anchoring the narration. In such a design, the contiguity principle still has currency – there should be facilitative positioning of text and diagrams.

The temporal contiguity principle asserts that

Students learn better when verbal and visual materials are temporally synchronized rather than separated in time.

However, this principle is a macro-level guideline that cannot help the practising multimedia designer. In fact, the authors and others have demonstrated that the principle does not hold unless the temporal separation is considerable (e.g. when a large chunk of animation is preceded by the whole narration). Compare this principle with the micro-level guidelines, 4.28 to 4.33 above, which exemplify the fine judgements of pacing and sequence made by the intuitive designer who gets inside the head of the learner.

Again, consider the redundancy principle, which asserts that

Students learn better from animation and narration than from animation, narration, and text if the visual information is presented simultaneously to the verbal information.

Once again, this principle assumes that the text is identical, word for word, with the narration. This approach was rejected a priori by UK OU designers, who surmised that simultaneous reading and listening would be uncomfortable (item 4.16 elucidates this rationale). Instead, the concern of OU designers is the subtle issue of how succinct the text should be in order to anchor the narration but not interfere with it (see 4.15 to 4.18).

As an aside, in contrast to the above deleterious effect of redundancy, there are many respects in which this book has recommended redundancy as being beneficial to learning, as a method of reinforcement or as compensating for cognitive overload or inattention. For example, one technique for moderating intellectual difficulty (principle 6e of Table 5.3) is to convert a long sentence into several shorter sentences. This necessitates repeating several words, which adds

Screenwriting principles for a multimedia package 219

some user-friendly redundancy. Then again, principle 8a of Table 5.3 recommends repetition from a different angle.

The coherence principle asserts that

Students learn better when extraneous material is excluded rather than included in multimedia explanations.

This principle was supported in an experiment by Moreno and Mayer (2000) in which learning was significantly worse when music was added to an animation with narration. This effect relates to one with a more evocative name, the seductive-augmentation effect – defined by Thalheimer (2004) as a negative effect on learning base material when the presentation is augmented by interesting but inessential text, sounds or visuals (the augmentation seduces the learner’s attention/processing away from the essential items). Thalheimer reviewed 24 research comparisons, 16 of which showed that adding interesting items hurt learning, 7 showed no difference and 1 showed a learning increment.

Intuitively we feel that making the presentation interesting is a good idea, because it engages the learner. But how does this fit with the above results? Here are two possibilities.

In the UK Open University, producers would typically spend hours choosing music that was appropriate to the mood of the story. Typically, even after sifting through printed descriptions of music tracks and discarding many choices, at least 80 per cent of the music tracks chosen for consideration were found to jar with the storyline. In any case, music was normally only played when there was a deliberate pause in the commentary, designed to allow viewers to reflect on the pictures. It is clear that the above experimenters did not follow these provisos, so it is not surprising that their music interfered with learning.

A second interpretation of the results is speculative but intriguing. All 16 experiments showing a significant negative effect involved very short learning tasks, average 4 minutes. An interesting conjecture by Thalheimer is that for longer tasks, in which attention might flag, adding interesting elements to sustain attention might have a positive effect on balance. That is, if the seductive augmentations do indeed cause a learning decrement (say 20 per cent), this may be the price we have to pay to keep learners attentive for longer periods. If seductive augmentations really do distract, the negative effect may be more than compensated by their sustained-attention effect.

To conclude, all six principles recommended by Moreno and Mayer (2000) are pitched at a macro-level that may be suitable for theory-building but that only skims the surface of the detailed design concerns of the practitioner.

A diligent search of the literature has failed to uncover any more practicable design principles. Admittedly, the six principles could serve as a useful backdrop for the practitioner. However, value is more likely to be obtained in the reverse direction. Namely, before we try to derive design principles based on macro-level learning theories, and refine them through experimental studies, we would be

220 Picture–word synergy for audiovision and multimedia

better advised to start from experienced teachers’ intuitive, micro-level design guidelines, and progress in the opposite direction, namely

micro-level design principles, as espoused above (a fledgling design theory)experimental studies refined theory/design principles …

Each of the proposed design principles could generate questions to be investigated.

•Regarding guideline 4.18, how should the screen text be phrased, in relation to the audio commentary, so that it anchors the commentary rather than interfering with it?

•Regarding guideline 4.21, just how sparse should the screen text be? Should the screens by themselves (without the audio) be just barely comprehensible to a really top expert in the subject-matter, or should they constitute a more substantial outline of the content?

Note that these questions concern the nature of the visual text rather than whether it is present or absent. This illustrates the philosophical conflict between the experimental studies and the design guidelines in this chapter. The guidelines aim to integrate narration and visuals (diagrams and visual text) in order to achieve optimum synergy between these two constituents. In contrast, the aforementioned experimental studies manipulate the two constituents separately, thereby compromising their synergy. As argued near the beginning of the chapter, a good media designer would rescript the narration if denied harmonious visuals and would redraft the visuals if denied harmonious narration. The above experimental studies could not countenance any such reconstruction of audio-visual synergy because this would have defeated their manipulation of the separate constituents!

Collaboration between researchers and practitioners would have a much increased chance of being productive if the investigations compared different ways of integrating narration and visuals – different composite designs aimed at optimum audio-visual synergy – rather than trying to unpick the two constituents and manipulate them separately.

A p p e n d i x e s

Telling the viewer about the story

i.e. explicit study guidance

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9d |

2d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2c |

Directing visual attention |

|

|||

|

|

|

2b |

|

10c |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2e |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

7a to 7c |

||

|

|

|

6a |

|

|

3a to 3c |

||

|

|

|

9c |

|

|

6b to 6g |

||

|

2a |

|

|

|

|

5a to 5e |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

5f |

||

|

|

|

|

4d |

|

4a to 4g |

||

9a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

(except 4d) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8a |

8b |

8c |

10a |

1b |

10b |

8d |

|

|

Telling the story |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Surreptitious |

(imparting the content) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cognitive scaffolding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by creating an |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

appropriate mindset |

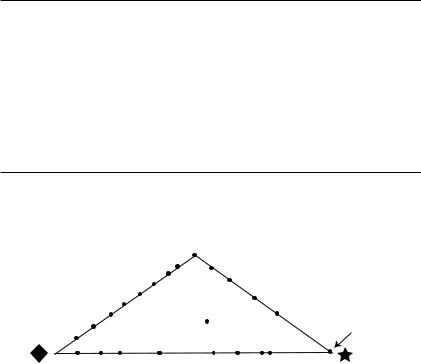

Figure A1.1 Alternative classification of the principles of Table 5.3, in terms of the three narrative archetypes of Figure 6.5. (Note. Principle 6g, Enhance legibility/ audibility, refers to a variety of techniques, most of which fall into the surreptitious category (bottom right), as indicated. However, those techniques under 6g for directing visual attention, such as highlighting portions of the screen, are largely explicit study guidance, hence these techniques are positioned near the top of the triangle, as shown.)

Table A2.1 Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (Anderson and Krathwohl (eds) 2001)

Simple to complex processing below but e.g. 2.7 is more complex than 3.1

1.Remember

1.1.Recognition

1.2.Recalling

2.Understand (grasp/construct meaning)

2.1Interpreting

2.2Exemplifying

2.3Classifying

2.4Summarizing

2.5Inferring

2.6Comparing

2.7Explaining

3.Apply

3.1Executing

3.2Implementing

4.Analyze

4.1Differentiating

4.2Organizing

4.3Attributing

A. Factual knowledge |

B. Conceptual knowledge |

C. Procedural knowledge |

D. Meta-cognitive knowledge |

||

a. terminology |

a. classifications |

a. |

skills or algorithms |

a. |

strategic |

b. details |

b. principles |

b. |

techniques/method |

b. cognitive task |

|

|

c. theories |

c. |

criteria for using |

|

(customize processing |

|

|

|

procedures |

|

according to task) |

|

|

|

|

c. |

self-knowledge |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.Evaluate

5.1Checking

5.2Critiquing

6.Create

6.1Generate

6.2Plan (design)

6.3Produce

Notes

These writers use a flipped version, with vertical Knowledge axis and horizontal Processes

Further elaboration can be found in LookSmart’s FindArticles > Theory into Practice 2002 http://www.findarticles.com/m0NQM/4_41/issue.jhtml In particular see the two articles: Rote versus meaningful learning (1) by Richard E. Mayer and

A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: an overview. (Benjamin S. Bloom, University of Chicago) by David R. Krathwohl