- •Contents

- •Предисловие

- •Методическая записка

- •Britain in ancient times. England in the Middle Ages.

- •1. The Earliest Settlers

- •3. The Anglo-Saxon period

- •The origin of day names

- •4. The Danish Invasion of Britain

- •5. Edward the Confessor

- •1. Beginning of the Norman invasion

- •2. The Norman Conquest

- •3. England in the Middle Ages

- •Church and State

- •Magna Carta and the beginning of Parliament

- •4. Language of the Norman Period

- •5. The development of culture

- •First universities

- •1. General characteristic of the period

- •2. Society

- •Peasants’ Revolt

- •3 Economic development of England

- •Agriculture and industry

- •4. Growth of towns

- •5. The Hundred Years War

- •6. Wars of the Roses

- •Geoffrey Chaucer

- •William Caxton

- •Music, theatre and art

- •Assignments (1)

- •1. Review the material of Section 1 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 1

- •2. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •III. Topics for presentations:

- •The English Renaissance

- •1. General characteristic of the period

- •2. The Great Discoveries

- •3. Absolute monarchy

- •4. Reformation

- •5. Counter-Reformation

- •6. Renaissance humanists

- •Elizabethan Age

- •1. The first playhouses

- •2. Actors and Society

- •3. London theatres

- •4. William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

- •5. Shakespeare and the language

- •1. The reign of James I

- •2. Strengthening of Parliament

- •3. Charles I and Parliament

- •4. The Civil War

- •5. Restoration of monarchy

- •6. Trade in the 17th century

- •7. Political parties

- •S 8. Science, Art and Music cience

- •J 9. Literature ournalism

- •Assignments (2)

- •I. Review the material of Section 2 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 2

- •II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •3. Topics for presentations:

- •Britain in the New Age. Modern Britain.

- •1. The Glorious Revolution

- •2. Political and economic development of the country

- •3. Life in town

- •4. London and Londoners

- •5. The Industrial Revolution

- •6. The Colonial Wars

- •7. The Development of arts

- •8. The Enlightenment

- •1. Napoleonic Wars

- •2. The political and economic development of the country

- •3. Romanticism

- •4. Art and artists

- •5. Victorian Age

- •Victorian Literature

- •1. The beginning of the century

- •2. Britain in World War I

- •3. Social issues in the 1920s

- •4. The General Strike and Depression

- •5. The Abdication

- •6. Britain in World War II

- •7. Britain in the post-war period

- •8. The fall of the colonial system

- •9. The Falklands War

- •10. Britain in international relations

- •11. Britain’s economic development at the end of the century

- •12. Social issues

- •13. 20Th-century literature

- •14. The development of the English language Changes in the language

- •In recent decades the English language in the uk has undergone certain phonetic, lexical and grammatical changes:

- •The spread of English. Variants of English.

- •Spelling differences

- •Phonetic differences

- •Lexical differences

- •Grammatical differences

- •Assignments (3)

- •I. Review the material of Section 3 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book. Test 3

- •II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- •III. Topics for presentations:

- •Cross-cultural notes Chapter 1

- •1. Iberians [aI'bi:rjRnz] – иберы/иберийцы (древние племена, жившие на территории Британских островов и Испании; в III–II вв. До н.Э. Завоеваны римлянами и романизированы.

- •Chapter 2

- •Chapter 3

- •Chapter 4

- •16. William Byrd [bR:d], Thomas Weelkes ['wi:lkIs], John Bull [bul] – Уильям Бэрд, Томас Уилкис, Джон Булл – английские композиторы конца XVI и начала XVII в. Chapter 5

- •8. Dark Lady – Смуглая Леди, незнакомка, часто упоминаемая в сонетах у. Шекспира. Chapter 6

- •Chapter 7

- •Chapter 9

- •Key to Tests

- •Электронный ресурс:

- •119454, Москва, пр. Вернадского, 76

- •119218, Москва, ул. Новочеремушкинская, 26

Britain in ancient times. England in the Middle Ages.

T

1. The Earliest Settlers

he Iberians

About 3 thousand years before our era the land we now call Britain was not separated from the continent by the English Channel and the North Sea. The Thames was a tributary of the Rhine. The snow did not melt on the mountains of Wales, Cumberland and Yorkshire even in summer. It lay there for centuries and formed rivers of ice called glaciers, that slowly flowed into the valleys below, some reaching as far as the Thames. At the end of the ice age the climate became warmer and the ice caps melted, flooding the lower-lying land that now lies under the North Sea and the English Channel. Many parts of Europe, including the present-day British Isles, were inhabited by the people who came to be known as the Iberians. Some of their descendants are still found in the North of Spain, populating the Iberian peninsular. Although little is known about the Iberians of the Stone Age, it is understood that they were a small, dark, long-headed race that settled especially on the chalk downs radiating from Salisbury Plain. All that is known about them comes from archaeological findings – the remains of their dwellings, their skeletons as well as some stone tools and weapons. The Iberians knew the art of grinding and polishing stone.

On the downs and along the oldest historic roads, the Icknield Way and the Pilgrim’s Way, lie long barrows, the great earthenworks which were burial places and prove the existence of marked class divisions. Other relics of the past are the stone circles of Stonehenge and Avebury on Salisbury Plain. Avebury is the grandest site while Stonehenge is the best known. The name of the place comes from the Saxon word Stanhengist, or “hanging stones”. Stonehenge is fifteen hundred years older than the Egyptian pyramids. It is made of stone gates standing in groups of twos. Each vertical stone weighs fifty tons or more. The flat stones joining the gates weigh 7 tons. Nobody knows why that huge double circle was build, or how primitive people managed to move such heavy stones. Some researchers think that it was built by the ancient Druids who performed their rites in Stonehenge. Others believe that it was built by the sun-worshippers who came to this distant land from the Mediterranean when the Channel was a dry valley on the Continent. Stonehenge might also have been an enormous calendar. Its changing shadows probably indicated the cycle of the seasons and told the people when it was time to sow their crops.

People and crops have vanished, but the stones stand fast and stubbornly keep their secrets from us.

The Celts

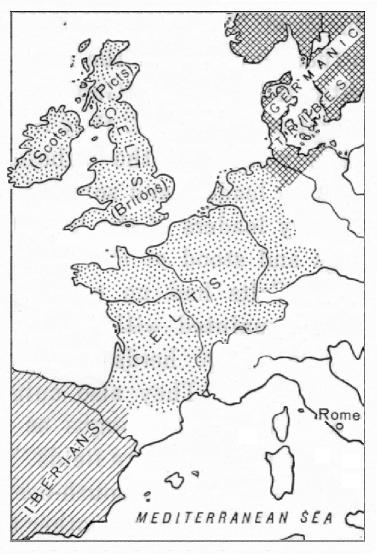

The period from the 6th to the 3rd century BC saw the migration of the people called the Celts. They spread across Europe from the East to the West and occupied the territory of the present-day France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland and Great Britain. (See Map 1.)

The Celtic tribes that crossed the Channel and landed on the British Isles were the Britons, the Scots, the Picts and the Gauls. The Britons populated the South, the Picts moved to the North, the Scots went to Ireland and the rest settled in between. Later, the Scots returned to the main island and in such numbers that the northern part of it got the name of Scotland. The history of the Picts and their struggle with the Scots was beautifully described by R.L. Stevenson in the ballad Heather Ale.

Map 1

(From S.D. Zaitseva. Early Britain. Moscow, 1975.)

In reality, the Picts were not exterminated but assimilated with the Scots. As for the Iberians, some of them were slain in battle, others were driven westwards into the mountains of Wales, the rest assimilated with the Celts. The last wave of the Celts were the Belgic tribes which arrived about 100 BC and occupied the south-east of the main island.

The Celts are known from the Travelling Notes by Pytheus, a traveller from Massilia (now – Marseilles). He visited the British Isles in the 4th century BC. Later, Herodotus wrote that even in the 5th century BC Phoenicians came to the British Isles for tin, which was used for making bronze. The British Isles were then called the Tin Islands.

Another person whom we owe reminiscences about early Britain is Guy Julius Caesar. In 55 BC his troops first landed in Britain. According to Caesar’s “Commentaries on the Gallic War,” the Celts, against whom he fought, were tall and blue-eyed people. Men had long moustaches (but no beards) and wore shirts, knee-long trousers and striped or checked cloaks which they fastened with a pin. (Later, their Scottish descendants developed it into tartan.) Both men and women were obsessed with the idea of cleanliness and neatness. As is known from reminiscences of the Romans, “neither man nor woman, however poor, was seen either ragged or dirty”.

Economically and socially the Celts were a tribal society made up of clans and tribes. The Celtic tribes were ruled by chiefs. The military leaders of the largest tribes were sometimes called kings. In wartime the Celts wore skins and painted their faces blue to make themselves look more fierce. They were armed with swords and spears and used war chariots in fighting. Women seem to have had extensive rights and independence and shared responsibility in defending their tribesmen. It is known that when the Romans invaded Britain, two of the largest tribes were ruled by women.

The Celts were pagans and their priests, the Druids, who were important members of the ruling class, preserved the tribal laws, religious teachings, history, medicine and other knowledge necessary in Celtic society. They worshipped in sacred places (on hills, by rivers, in groves of trees) and their rites sometimes included human sacrifice.

The Celts lived in villages and practised a primitive agriculture: they used light ploughs and grew their crops in small square fields. They knew the use of copper, tin, and iron, kept large herds of cattle and sheep which formed their chief wealth.

The Celts traded both inside and beyond Britain. On the Continent, the Celtic tribes of Britain carried on trade with Celtic Gaul. Trade was also an important political and social factor in relationship between tribes. Most trade was conducted by sea or river. It is no accident that the capitals of England and Scotland appeared on the river banks, in place of the old trade routes. The settlement on the Thames, which existed before London, was a major trade outpost eastwards to Europe.

The descendants of the ancient Celts live on the British Isles up to this day. They are the Welsh, the Scottish and the Irish. The Welsh language, which belongs to the Celtic group, is the oldest living language in Europe. In the Highlands of Scotland, as well as in the western parts of Ireland, there is still a strong influence of the Celtic language. Some words of the Celtic origin still exist in Modern English. Scholars believe that about a dozen common nouns are of the Celtic origin; among these are cradle, bannock, cart, down, loch (dial.), coomb (dial.), mattock. Most others are geographical names. These are the names of Celtic settlements which later grew into towns: London, Leeds and Kent which got its name after the name of a Celtic tribe. There are several rivers in England which still bear Celtic names: Avon and Evan, Thames, Severn, Mersey, Derwent, Ouse, Exe, Esk, Usk. The Celtic word loch is still used in Scotland to denote a lake: Loch Ness, Loch Lomond.

Celtic borrowings in English

Modern English |

Celtic |

meaning |

Avon, Evan |

amhiun |

river |

Ouse, Exe, Esk, Usk |

uisge |

water |

Dundee, Dumbarton, Dunscore; the Downs |

dun |

hill; bare, open highland |

Kilbrook |

coill |

wood |

Batcombe, Duncombe |

comb |

deep valley |

Ben-Nevis, Ben-More |

bein |

mountain |

F

2.

Roman Britain

In the ninety years between the first two raids and the invasion of the Romans in AD 43, a thorough economic development in South-East Britain went on. Traders and colonists settled in large numbers and the growth of towns was so considerable that in AD 50, only seven years after the invasion of Claudius, Verulamium (now St. Albans) was granted the full status of a Roman town (municipium) with self-government and the rights of Roman citizenship for its inhabitants.

It would be wrong to assume that the Celts eagerly surrendered to the invaders. The hilly districts in the West were very difficult to subdue, and the Romans had to set up many camps in that part of the country and station their legions all over Britain to defend the province.

The Celts fought fiercely against the Romans who never managed to become masters of the whole island. In AD 61-62 Queen Boadicea (Boadica) led her tribesmen against the Romans. Upon her husband’s death, she managed to raise an army which raided the occupied territories slaying the Romans and their supporters, burning down and ruining the Roman towns and nearly bringing an end to the Roman rule of Britain as such. It was only when she was captured by the Roman soldiers and took poison that peace was restored in the province.

The Romans were also unable to conquer the Scottish Highlands, or Caledonia as they called it, thus the province of Britain covered only the southern part of the island. From time to time the Picts from the North managed to raid the Roman part of the island, burn their villages, and drive off their cattle and sheep. During the reign of the Emperor Hadrian a high wall was built in the North to defend the province from the raids of the Picts and the Scots. (See Map 2.) The wall, known as Hadrian’s Wall, stretches from the eastern to the western coast of the island. With its forts, built a mile apart one from another, the wall served as a stronghold in the North. At the same time, when the Northern Britons were not at war with the Romans, the wall turned into an improvised market place for either party.

In AD 139 – 42 the Emperor Antoninus Pius abandoned Hadrian’s Wall and constructed a new frontier defence system between the Forth and the Clyde – the Antonine Wall – but its use was short-lived and Hadrian’s Wall was again the main northern frontier by AD 164.

One of the greatest achievements of the Roman Empire was its system of roads, in Britain no less than elsewhere. When the legions arrived in Britain in the first century AD, their first task was to build a system of roads. Stone bridges were built across rivers. Roman roads were made of of stones, lime and gravel. They were vital not only for the speedy movement of troops and supplies from one strategic center to another, but also allowed the movement of agricultural products from farm to market.

Map 2

(From S.D. Zaitseva. Early Britain. Moscow, 1975.)

Within a generation the British landscape changed considerably. London became the chief administrative centre. From it, roads spread out to all parts of the province. Some of the roads exist up to this day, for example Watling Street which stretched from Dover to London, then to Chester and into the mountains of Wales. Unlike the Celts, who lived in villages, the Romans were city-dwellers. The Roman army built legionary fortresses, forts, camps, and roads, and assisted with the construction of buildings in towns. The Romans built most towns to a standardized pattern of straight, parallel main streets that crossed at right angles. The forum (market place) formed the centre of each town. Shops and such public buildings as the basilica, baths, law-courts, and temple surrounded the forum. The paved streets had drainage systems, and fresh water was piped to many buildings. Houses were built of wood or narrow bricks and had tiled roofs.

The chief towns were Colchester, Gloucester, York, Lincoln, Dover, Bath and London (or Londinium). It is common knowledge that London was founded by the Romans in place of an earlier settlement.

Roman towns fell into one of three main types: coloniae, municipia and civitates. The coloniae of Roman Britain were Colchester, Lincoln, Gloucester, York, and possibly London, and their inhabitants were Roman citizens. The only certain municipia was Verulamium (St. Albans), a self-governing community with certain legal privileges. The civitates, towns of non-citizens, included most of Britain’s administrative centres.

The Romans also brought their style of architecture to the countryside in the form of villas. Some very large early villas are known in Kent and in Sussex.

Both public buildings and private dwellings were decorated in imitation of the Roman style. Sculpture and wall painting were both novelties in Roman Britain. Statues or busts in bronze or marble were imported from Mediterranean workshops, but British sculptures soon learned their trade and produced attractive works of their own. Mosaic floors, found in towns and villas, were at first laid by imported craftsmen. But there is evidence that by the middle of the 2nd century a local firm was at work at Colchester and Verulamium, and in the 4th century a number of local mosaic workshops can be recognized by their styles.

When Christianity gained popularity in the Empire, it also spread to the provinces and was established in Britain in the 300s. The first English martyr was St. Alban who died about 287.

In 306, Constantine the Great, the son of Constantine Chlora and Elene (Helen), the daughter of a British chief, became the Roman Emperor. He stopped the persecution of Christians and became a Christian himself. All Christian churches were centralised in Constantinople which was made the capital of the Empire. This religion came to be known as the Catholic Church. (‘catholic’ means ‘universal’.) Greek and Latin became the languages of the Church all over Europe including Britain.

Literary evidence suggests that Britons adopted Latinized names and that the elite spoke and wrote Latin. The largest number of Latin words was introduced as a result of the spread of Christianity: abbot, altar, angel, creed, hymn, idol, organ, nun, pope, temple and many others. The traces of Latin are still found in modern English:

Latin borrowings in English

Modern English |

Latin |

meaning |

Chester, Doncaster, Gloucester |

castra |

camp |

street, Stratford |

strata via |

a paved road |

wall |

vallum |

a wall of fortifications |

Lincoln, Colchester |

colonia |

colony |

Devonport |

portus |

port, haven |

Norwich, Woolwich |

vicus |

village |

Chepstow; Chapman |

caupo |

a small tradesman |

pound |

(pondo) pondus |

(measure of) weight |

mile |

millia passum |

1000 steps |

piper |

pepper |

перец |

wine |

vinum |

вино |

butter |

butyrum |

масло |

cheese |

caseus |

сыр |

pear |

pirum |

груша |

mill |

molinum |

мельница |

Despite the growth of towns and all the other essentials of civilization that came with the Roman conquest, the standards of living changed little. Britain was an agricultural province, dependent on small farms. Peasants still built round Celtic huts and worked in the fields in the same way. Despite the 400 years of Roman influence, Britain was still largely a Celtic society.

The conquest of Britain by the Roman Empire lasted up to the beginning of the 5th century. In 410 the Roman legions were called back to Rome, and those that stayed behind were to become the Romanized Celts (Britons) who faced the invasion of the barbarians – the Germanic tribes of Angles and Saxons.