Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Other Causes

Treatments. Prosthetic valve replacement may cause variable murmurs, depending on the location, valve composition, and method of operation.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as electrocardiography, echocardiography, and angiography. Administer an antibiotic and an anticoagulant as appropriate. Because a cardiac abnormality is frightening to the patient, provide emotional support.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms the patient should report and the use of prophylactic antibiotics, if appropriate.

Pediatric Pointers

Innocent murmurs, such as Still’s murmur, are commonly heard in young children and typically disappear in puberty. Pathognomonic heart murmurs in infants and young children usually result from congenital heart disease, such as atrial and ventricular septal defects. Other murmurs can be acquired, as with rheumatic heart disease.

REFERENCES

Geliki, K. A., Sotirios, F. , Sotirios, T. , Alexandra, M. , Gabriel, D., & Stefanos, M. (2011) . Accuracy of cardiac auscultation in asymptomatic neonates with heart murmurs: Comparison between pediatric trainees and neonatologists. Pediatric Cardiology , 32, 473–477.

Gokman, Z., Tunaoglu, F. S. , Kula, S., Ergenekon, E., Ozkiraz, S., & Olgunturk, R. (2009). Comparison of initial evaluation of neonatal murmurs by pediatrician and pediatric cardiologist. Journal of Fetal Neonatal Medicine, 22, 1086–1091.

Muscle Atrophy[Muscle wasting]

Muscle atrophy results from denervation or prolonged muscle disuse. When deprived of regular exercise, muscle fibers lose bulk and length, producing a visible loss of muscle size and contour and apparent emaciation or deformity in the affected area. Even slight atrophy usually causes some loss of motion or power.

Atrophy usually results from neuromuscular disease or injury. However, it may also stem from certain metabolic and endocrine disorders and prolonged immobility. Some muscle atrophy also occurs with aging.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when and where he first noticed the muscle wasting and how it has progressed. Also ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as weakness, pain, loss of sensation, and recent weight loss. Review the patient’s medical history for chronic illnesses; musculoskeletal or neurologic disorders, including trauma; and endocrine and metabolic disorders. Ask about his use of alcohol and drugs, particularly steroids.

Begin the physical examination by determining the location and extent of atrophy. Visually evaluate small and large muscles. Check all major muscle groups for size, tonicity, and strength. (See Testing Muscle Strength , pages 488 and 489.) Measure the circumference of all limbs, comparing sides. (See Measuring Limb Circumference .) Check for muscle contractures in all limbs by fully extending joints and noting pain or resistance. Complete the examination by palpating peripheral pulses for quality and rate, assessing sensory function in and around the atrophied area, and testing deep tendon reflexes (DTRs).

Medical Causes

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Initial symptoms of ALS include muscle weakness and atrophy that typically begin in one hand, spread to the arm, and then develop in the other hand and arm. Eventually, weakness and atrophy spread to the trunk, neck, tongue, larynx, pharynx, and legs; progressive respiratory muscle weakness leads to respiratory insufficiency. Other findings include muscle flaccidity, fasciculations, hyperactive DTRs, slight leg muscle spasticity, dysphagia, impaired speech, excessive drooling, and depression.

Burns. Fibrous scar tissue formation, pain, and loss of serum proteins from severe burns can limit muscle movement, resulting in atrophy.

Hypothyroidism. Reversible weakness and atrophy of proximal limb muscles may occur in hypothyroidism. Associated findings commonly include muscle cramps and stiffness; cold intolerance; weight gain despite anorexia; mental dullness; dry, pale, cool, doughy skin; puffy face, hands, and feet; and bradycardia.

Meniscal tear. Quadriceps muscle atrophy, resulting from prolonged knee immobility and muscle weakness, is a classic sign of meniscal tear, a traumatic disorder.

Multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis is a degenerative disease that may produce arm and leg atrophy as a result of chronic progressive weakness; spasticity and contractures may also develop. Associated signs and symptoms typically wax and wane and include diplopia and blurred vision, nystagmus, hyperactive DTRs, sensory loss or paresthesia, dysarthria, dysphagia, incoordination, an ataxic gait, intention tremors, emotional lability, impotence, and urinary dysfunction.

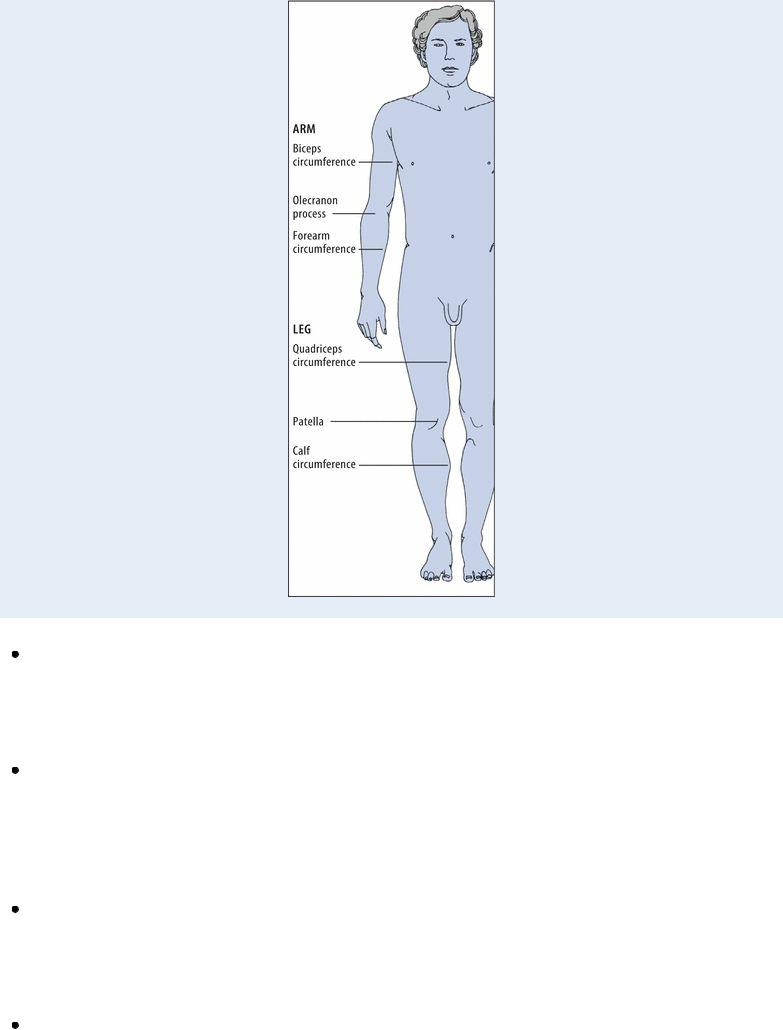

EXAMINATION TIP Measuring Limb Circumference

EXAMINATION TIP Measuring Limb Circumference

To ensure accurate and consistent limb circumference measurements, mark and use a consistent reference point each time and measure with the limb in full extension. The illustration below shows the correct reference points for arm and leg measurements.

Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is a chronic disorder that eventually causes atrophy proximal to involved joints as a result of progressive weakness and disuse. Other late signs and symptoms include bony joint deformities, such as Heberden’s nodes on the distal interphalangeal joints, Bouchard’s nodes on the proximal interphalangeal joints, crepitus and fluid accumulation, and contractures.

Parkinson’s disease . With Parkinson’s disease, muscle rigidity, weakness, and disuse may produce muscle atrophy. The patient may exhibit insidious resting tremors that usually begin in the fingers (pill-rolling tremor), worsen with stress, and ease with purposeful movement and sleep. He may also develop bradykinesia; a characteristic propulsive gait; a high-pitched, monotone voice; masklike facies; drooling; dysphagia; dysarthria; and, occasionally, oculogyric crisis or blepharospasm.

Peripheral neuropathy. With peripheral neuropathy, muscle weakness progresses slowly to flaccid paralysis and eventually atrophy. Distal extremity muscles are generally affected first. Associated findings include a loss of vibration sense; paresthesia, hyperesthesia, or anesthesia in the hands and feet; mild to sharp, burning pain; anhidrosis; glossy red skin; and diminished or absent DTRs.

Protein deficiency. If chronic, protein deficiency may lead to muscle weakness and atrophy.

Other findings include chronic fatigue, apathy, anorexia, dry skin, peripheral edema, and dull, sparse, dry hair.

Rheumatoid arthritis. Muscle atrophy occurs in the late stages of rheumatoid arthritis as joint pain and stiffness decrease range of motion (ROM) and discourage muscle use.

Spinal cord injury. Trauma to the spinal cord can produce severe muscle weakness and flaccid, then spastic, paralysis, eventually leading to atrophy. Other signs and symptoms depend on the level of injury but may include respiratory insufficiency or paralysis, sensory losses, bowel and bladder dysfunction, hyperactive DTRs, a positive Babinski’s reflex, sexual dysfunction, priapism, hypotension, and anhidrosis (usually unilateral).

Other Causes

Drugs. Prolonged steroid therapy interferes with muscle metabolism and leads to atrophy, most prominently in the limbs.

Immobility. Prolonged immobilization from bed rest, casts, splints, or traction may cause muscle weakness and atrophy.

Special Considerations

Because contractures can occur as atrophied muscle fibers shorten, help the patient maintain muscle length by encouraging him to perform frequent, active ROM exercises. If he can’t actively move a joint, provide active assistive or passive exercises, and apply splints or braces to maintain muscle length. If you find resistance to full extension during exercise, use heat, pain medication, or relaxation techniques to relax the muscle. Then slowly stretch it to full extension. (Caution: Don’t pull or strain the muscle; you may tear muscle fibers and cause further contracture.) If these techniques fail to correct the contracture, use moist heat, a whirlpool bath, resistive exercises, or ultrasound therapy. If these techniques aren’t effective, surgical release of contractures may be necessary.

Teach the patient to use necessary assistive devices properly to ensure his safety and prevent falls. Have the patient consult a physical therapist for a specialized therapy regimen.

Prepare the patient for electromyography, nerve conduction studies, muscle biopsy, and X-rays or computed tomography scans.

Patient Counseling

Show the patient how to use assistive devices, as needed, and emphasize safety measures he should adopt. Teach the patient an exercise regimen to follow.

Pediatric Pointers

In young children, profound muscle weakness and atrophy can result from muscular dystrophy. Muscle atrophy may also result from cerebral palsy and poliomyelitis and from paralysis associated with meningocele and myelomeningocele.

REFERENCES

Belavý, D. L., Ng, J. K., & Wilson, S. J., Armbrecht, G., Stegeman, D. F., Rittweger, J., …, Richardson, C. A. (2009) . Influence of prolonged bed-rest on spectral and temporal electromyographic motor control characteristics of the superficial lumbo-pelvic

musculature. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 20, 170–179.

Claus, A. P. , Hides, J. A., & Moseley, G. L., Hodges, P. W. (2009). Different ways to balance the spine: Subtle changes in sagittal spinal curves affect regional muscle activity. Spine, 34, 208–214.

Muscle Flaccidity[Muscle hypotonicity]

Flaccid muscles are profoundly weak and soft, with decreased resistance to movement, increased mobility, and a greater than normal range of motion (ROM). The result of disrupted muscle innervation, flaccidity can be localized to a limb or muscle group or generalized over the entire body. Its onset may be acute, as in trauma, or chronic, as in neurologic disease.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient’s muscle flaccidity results from trauma, make sure his cervical spine has been stabilized. Quickly determine his respiratory status. If you note signs and symptoms of respiratory insufficiency — dyspnea, shallow respirations, nasal flaring, cyanosis, and decreased oxygen saturation — administer oxygen by nasal cannula or mask. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, ask about the onset and duration of muscle flaccidity and precipitating factors. Ask about associated symptoms, notably weakness, other muscle changes, and sensory loss or paresthesia.

Examine the affected muscles for atrophy, which indicates a chronic problem. Test muscle strength, and check deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in all limbs.

Medical Causes

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Progressive muscle weakness and paralysis are accompanied by generalized flaccidity. Typically, these effects begin in one hand, spread to the arm, and then develop in the other hand and arm. Eventually, they spread to the trunk, neck, tongue, larynx, pharynx, and legs; progressive respiratory muscle weakness leads to respiratory insufficiency. Other findings include muscle cramps and coarse fasciculations, hyperactive DTRs, slight leg muscle spasticity, dysphagia, dysarthria, excessive drooling, and depression.

Brain lesions. Frontal and parietal lobe lesions may cause contralateral flaccidity, weakness or paralysis and, eventually, spasticity and possibly contractures. Other findings include hyperactive DTRs, a positive Babinski’s sign, loss of proprioception, stereognosis, graphesthesia, anesthesia, and thermanesthesia.

Guillain-Barré syndrome. Guillain-Barré syndrome causes muscle flaccidity. Progression is typically symmetrical and ascending, moving from the feet to the arms and facial nerves within 24 to 72 hours of its onset. Associated findings include sensory loss or paresthesia, absent DTRs, tachycardia (or, less commonly, bradycardia), fluctuating hypertension and orthostatic hypotension, diaphoresis, incontinence, dysphagia, dysarthria, hypernasality, and facial diplegia. Weakness may progress to total motor paralysis and respiratory failure.

Huntington’s disease. Besides flaccidity, progressive mental status changes up to and including dementia and choreiform movements are major symptoms. Others include poor balance, hesitant or explosive speech, dysphagia, impaired respirations, and incontinence.

Muscle disease. Muscle weakness and flaccidity are features of myopathies and muscular dystrophies.

Peripheral nerve trauma. Flaccidity, paralysis, and loss of sensation and reflexes in the innervated area can occur.

Peripheral neuropathy. Flaccidity usually occurs in the legs as a result of chronic progressive muscle weakness and paralysis. It may also cause mild to sharp burning pain, glossy red skin, anhidrosis, and a loss of vibration sensation. Paresthesia, hyperesthesia, or anesthesia may affect the hands and feet. DTRs may be hypoactive or absent.

Seizure disorder. Brief periods of syncope and generalized flaccidity commonly follow a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Spinal cord injury. Spinal shock can result in acute muscle flaccidity or spasticity below the level of injury. Associated signs and symptoms also occur below the level of injury and may include paralysis; absent DTRs; analgesia; thermanesthesia; loss of proprioception and vibration, touch, and pressure sensation; and anhidrosis (usually unilateral). Hypotension, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and impotence or priapism may also occur. Injury in the C1 to C5 region can produce respiratory paralysis and bradycardia.

Special Considerations

Provide regular, systematic, passive ROM exercises to preserve joint mobility and increase circulation. Reposition a patient with generalized flaccidity every 2 hours to protect him from skin breakdown. Pad bony prominences and other pressure points, and prevent thermal injury by testing bath water yourself before the patient bathes. Treat isolated flaccidity by supporting the affected limb in a sling or with a splint. Ensure patient safety and reduce the risk of falls by introducing assistive devices and teaching their proper use. Consult a physician and an occupational therapist to formulate a personalized therapy regimen and foster independence.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as cranial and spinal X-rays, computed tomography scans, and electromyography.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to use assistive devices, and review the prescribed exercise regimen with him.

Pediatric Pointers

Pediatric causes of muscle flaccidity include myelomeningocele, Lowe’s disease, Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, and muscular dystrophy. An infant or young child with generalized flaccidity may lie in a froglike position, with his hips and knees abducted.

REFERENCES

Ageno, W., Agnelli, G., & Checchia, G., Cimminiello, C., Paciaroni, M., Palareti, G., … Testa, S.; Italian Society for Haemostasis and Thrombosis. (2009). Prevention of venous thromboembolism in immobilized neurological patients: Guidelines of the Italian Society for Haemostasis and Thrombosis (SISET). Thrombosis Research, 124(5), 26–31.

van Hedel, H. J., & Dietz, V. (2010). Rehabilitation of locomotion after spinal cord injury. Restoration Neurology and Neuroscience ,

28(1), 123–134.

Muscle Spasms

(See Also Muscle Spasticity) [Muscle cramps]

Muscle spasms are strong, painful contractions. They can occur in virtually any muscle but are most common in the calf and foot. Muscle spasms typically occur from simple muscle fatigue, after exercise, and during pregnancy. However, they may also develop in electrolyte imbalances and neuromuscular disorders or as the result of certain drugs. They’re typically precipitated by movement, especially a quick or jerking movement, and can usually be relieved by slow stretching.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient complains of frequent or unrelieved spasms in many muscles, accompanied by paresthesia in his hands and feet, quickly attempt to elicit Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs. If these signs are present, suspect hypocalcemia. Evaluate respiratory function, watching for the development of laryngospasm; provide supplemental oxygen as necessary, and prepare to intubate the patient and provide mechanical ventilation. Draw blood for calcium and electrolyte levels and arterial blood gas analysis, and insert an I.V. line for administration of a calcium supplement. Monitor the patient’s cardiac status, and prepare to begin resuscitation if necessary.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, ask when the spasms began. Is there a particular activity that precipitates them? How long did they last? How painful were they? Did anything worsen or lessen the pain? Ask about other symptoms, such as weakness, sensory loss, or paresthesia.

Evaluate muscle strength and tone. Then, check all major muscle groups and note whether movements precipitate spasms. Test the presence and quality of all peripheral pulses, and examine the limbs for color and temperature changes. Test the capillary refill time (normal is less than 3 seconds), and inspect for edema, especially in the involved area. Observe for signs and symptoms of dehydration such as dry mucous membranes. Obtain a thorough drug and diet history. Ask the patient if he has had recent vomiting or diarrhea. Finally, test reflexes and sensory function in all extremities.

Medical Causes

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). With ALS, muscle spasms may accompany progressive muscle weakness and atrophy that typically begin in one hand, spread to the arm, and then spread to the other hand and arm. Eventually, muscle weakness and atrophy affect the trunk, neck, tongue, larynx, pharynx, and legs; progressive respiratory muscle weakness leads to respiratory insufficiency. Other findings include muscle flaccidity progressing to spasticity, coarse fasciculations, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), dysphagia, impaired speech, excessive drooling, and depression.

Arterial occlusive disease. Arterial occlusion typically produces spasms and intermittent claudication in the leg, with residual pain. Associated findings are usually localized to the legs and feet and include loss of peripheral pulses, pallor or cyanosis, decreased sensation, hair loss, dry or scaling skin, edema, and ulcerations.

Cholera. Muscle spasms, severe water and electrolyte loss, thirst, weakness, decreased skin turgor, oliguria, tachycardia, and hypotension occur along with abrupt watery diarrhea and vomiting.

Dehydration. Sodium loss may produce limb and abdominal cramps. Other findings include a slight fever, decreased skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, muscle twitching, seizures, nausea, vomiting, and oliguria.

Hypocalcemia. The classic feature is tetany — a syndrome of muscle cramps and twitching, carpopedal and facial muscle spasms, and seizures, possibly with stridor. Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs may be elicited. Related findings include paresthesia of the lips, fingers, and toes; choreiform movements; hyperactive DTRs; fatigue; palpitations; and cardiac arrhythmias.

Muscle trauma. Excessive muscle strain may cause mild to severe spasms. The injured area may be painful, swollen, reddened, or warm.

Respiratory alkalosis. The acute onset of muscle spasms may be accompanied by twitching and weakness, carpopedal spasms, circumoral and peripheral paresthesia, vertigo, syncope, pallor, and extreme anxiety. With severe alkalosis, cardiac arrhythmias may occur.

Spinal injury or disease. Muscle spasms can result from spinal injury, such as a cervical extension injury or spinous process fracture, or from spinal disease such as infection.

Other Causes

Drugs. Common spasm-producing drugs include diuretics, corticosteroids, and estrogens.

Special Considerations

Depending on the cause, help alleviate the patient’s spasms by slowly stretching the affected muscle in the direction opposite the contraction. If necessary, administer a mild analgesic.

Diagnostic studies may include serum calcium, sodium and carbon dioxide levels, thyroid function tests, and blood flow studies or arteriography.

Patient Counseling

Discuss pain relief measures. Explain immobilization and how to wrap the injured area. Teach the patient to use assistive devices, as needed.

Pediatric Pointers

Muscle spasms rarely occur in children. However, their presence may indicate hypoparathyroidism, osteomalacia, rickets or, rarely, congenital torticollis.

REFERENCES

Katzberg, H. D., Khan, A. H., & So, Y. T. (2010) . Assessment and symptomatic treatment for muscle cramps (an evidence-based review): Report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology . Neurology,

74, 691–696.

Miller, K. C., & Knight, K. L. (2009). Electrical stimulation cramp threshold frequency correlates well with the occurrence of skeletal muscle cramps. Muscle Nerve, 39, 364–368.

Muscle Spasticity

(See Also Muscle Spasms) [Muscle hypertonicity]

Spasticity is a state of excessive muscle tone manifested by increased resistance to stretching and heightened reflexes. It’s commonly detected by evaluating a muscle’s response to passive movement; a spastic muscle offers more resistance when the passive movement is performed quickly. Caused by an upper motor neuron lesion, spasticity usually occurs in the arm and leg muscles. Long-term spasticity results in muscle fibrosis and contractures. (See How Spasticity Develops.)

History and Physical Examination

When you detect spasticity, ask the patient about its onset, duration, and progression. What, if any, events precipitate its onset? Has he experienced other muscular changes or related symptoms? Does his medical history reveal an incidence of trauma or a degenerative or vascular disease?

Take the patient’s vital signs, and perform a complete neurologic examination. Test reflexes and evaluate motor and sensory function in all limbs. Evaluate muscles for wasting and contractures.

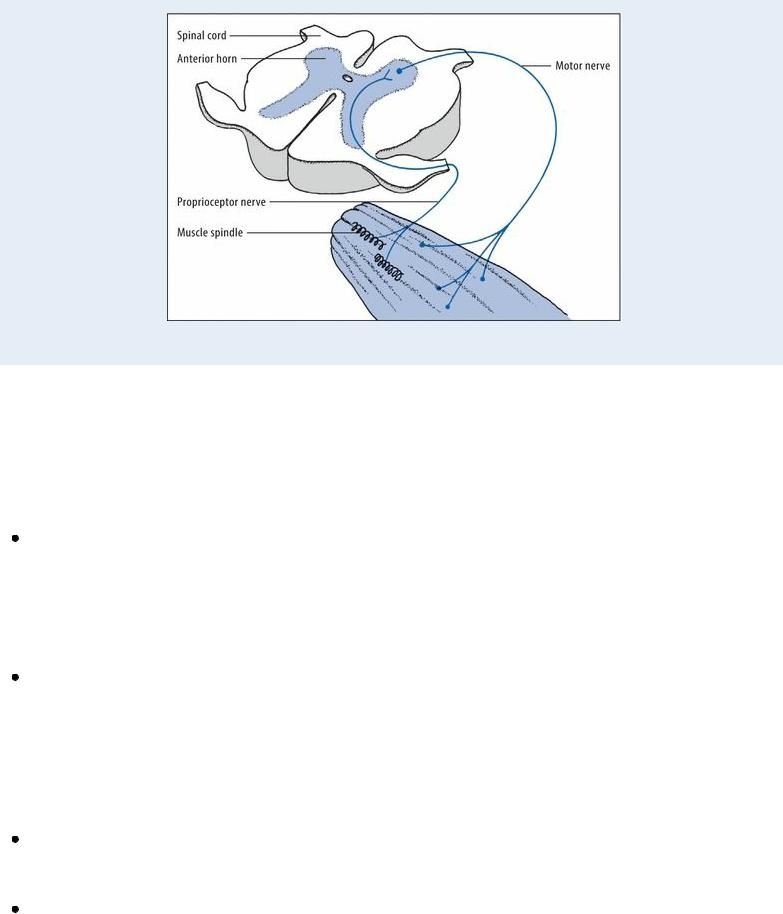

How Spasticity Develops

Motor activity is controlled by pyramidal and extrapyramidal tracts that originate in the motor cortex, basal ganglia, brain stem, and spinal cord. Nerve fibers from the various tracts converge and synapse at the anterior horn in the spinal cord. Together, they maintain segmental muscle tone by modulating the stretch reflex arc. This arc, shown in simplified form below, is basically a negative feedback loop in which muscle stretch (stimulation) causes reflexive contraction (inhibition), thus maintaining muscle length and tone.

Damage to certain tracts results in a loss of inhibition and a disruption of the stretch reflex arc. Uninhibited muscle stretch produces exaggerated, uncontrolled muscle activity, accentuating the reflex arc and eventually resulting in spasticity.

During your examination, keep in mind that generalized spasticity and trismus in a patient with a recent skin puncture or laceration indicates tetanus. If you suspect this rare disorder, look for signs of respiratory distress. Provide ventilatory support, if necessary, and monitor the patient closely.

Medical Causes

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS commonly produces spasticity, spasms, coarse fasciculations, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes (DTRs), and a positive Babinski’s sign. Earlier effects include progressive muscle weakness and flaccidity that typically begin in the hands and arms and eventually spread to the trunk, neck, larynx, pharynx, and legs; progressive respiratory muscle weakness leads to respiratory insufficiency. Other findings include dysphagia, dysarthria, excessive drooling, and depression.

Epidural hemorrhage. With epidural hemorrhage, bilateral limb spasticity is a late and ominous sign. Other findings include a momentary loss of consciousness after head trauma, followed by a lucid interval and then a rapid deterioration in the level of consciousness (LOC). The patient may also develop unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia; seizures; fixed, dilated pupils; a high fever; a decreased and bounding pulse; a widened pulse pressure; elevated blood pressure; an irregular respiratory pattern; and decerebrate posture. A positive Babinski’s sign can be elicited.

Multiple sclerosis. Muscle spasticity or stiffness can occur in patients with multiple sclerosis. Other symptoms may include weakness and loss of sensation in the limbs, an uncoordinated gait, vision disturbances, and dizziness.

Spinal cord injury. Spasticity commonly results from cervical and high thoracic spinal cord injury, especially from incomplete lesions. Spastic paralysis in the affected limbs follows initial flaccid paralysis; typically, spasticity and muscle atrophy increase for up to 1¼ to 2 years after the injury and then gradually regress to flaccidity. Associated signs and symptoms vary with the level of injury but may include respiratory insufficiency or paralysis, sensory losses, bowel and bladder dysfunction, hyperactive DTRs, a positive Babinski’s sign, sexual dysfunction,