Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

discolored gums.

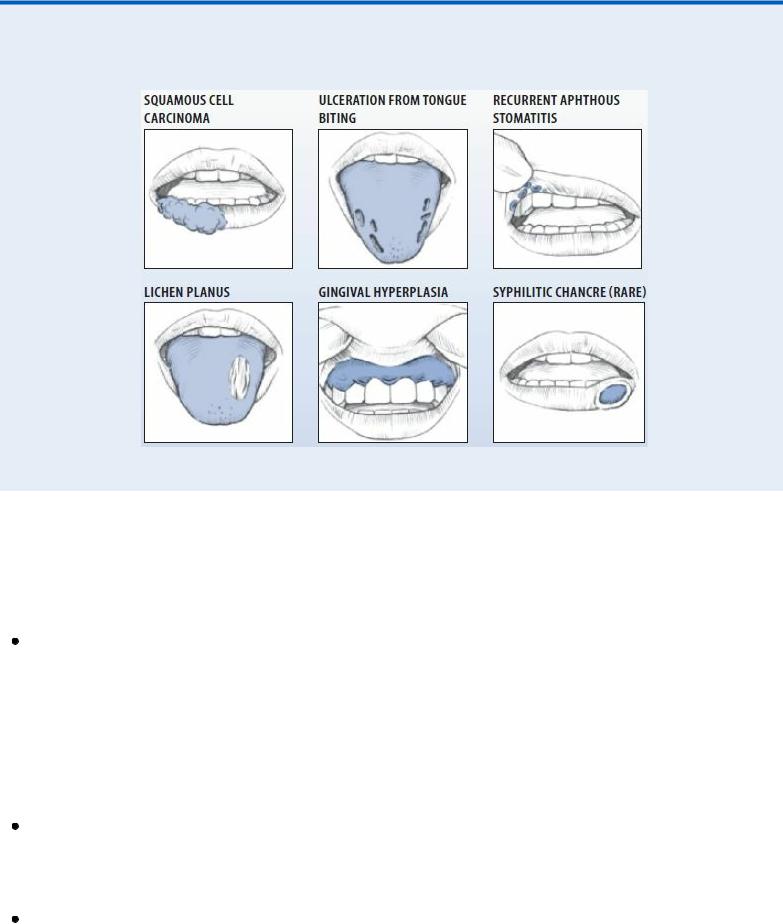

Common Mouth Lesions

Palpate the neck for adenopathy, especially in patients who smoke tobacco or use alcohol excessively.

Medical Causes

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Oral lesions may be an early indication of the immunosuppression that’s characteristic of AIDS. Fungal infections can occur, with oral candidiasis being the most common. Bacterial or viral infections of the oral mucosa, tongue, gingivae, and periodontal tissue may also occur.

The primary oral neoplasm associated with AIDS is Kaposi’s sarcoma. The tumor is usually found on the hard palate and may appear initially as an asymptomatic, flat or raised lesion, ranging in color from red to blue to purple. As these tumors grow, they may ulcerate and become painful.

Actinomycosis (cervicofacial). Actinomycosis is a chronic fungal infection that typically produces small, firm, flat, and usually painless swellings on the oral mucosa and under the skin of the jaw and neck. Swellings may indurate and abscess, producing fistulas and sinus tracts with a characteristic purulent yellow discharge.

Behçet’s syndrome . Behçet’s syndrome is a chronic, progressive syndrome that generally affects young males and produces small, painful ulcers on the lips, gums, buccal mucosa, and tongue. In severe cases, the ulcers also develop on the palate, pharynx, and esophagus. The

ulcers typically have a reddened border and are covered with a gray or yellow exudate. Similar lesions appear on the scrotum and penis or labia majora; small pustules or papules on the trunk and limbs; and painful erythematous nodules on the shins. Ocular lesions may also develop.

Candidiasis. Candidiasis is a common fungal infection that characteristically produces soft, elevated plaques on the buccal mucosa, tongue, and sometimes the palate, gingivae, and floor of the mouth; the plaques may be wiped away. The lesions of acute atrophic candidiasis are red and painful. The lesions of chronic hyperplastic candidiasis are white and firm. Localized areas of redness, pruritus, and a foul odor may be present.

Discoid lupus erythematosus. Oral lesions are common, typically appearing on the tongue, buccal mucosa, and palate as erythematous areas with white spots and radiating white striae. Associated findings include skin lesions on the face, possibly extending to the neck, ears, and scalp; if the scalp is involved, alopecia may result. Hair follicles are enlarged and filled with scale.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

This chronic, recurrent disease is most common in women ages 30 to 40.

Erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme is an acute inflammatory skin disease that produces a sudden onset of vesicles and bullae on the lips and buccal mucosa. Also, erythematous macules and papules form symmetrically on the hands, arms, feet, legs, face, and neck and, possibly, in the eyes and on the genitalia. Lymphadenopathy may also occur. With visceral involvement, other findings include a fever, malaise, a cough, throat and chest pain, vomiting, diarrhea, myalgia, arthralgia, fingernail loss, blindness, hematuria, and signs of renal failure.

Gingivitis (acute necrotizing ulcerative). Gingivitis is a recurring periodontal condition that causes a sudden onset of gingival ulcers covered with a grayish white pseudomembrane. Other findings include tender or painful gingivae, intermittent gingival bleeding, halitosis, enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, and a fever.

Herpes simplex 1. With primary infection, a brief period of prodromal tingling and itching, which is accompanied by a fever and pharyngitis, is followed by eruption of small and irritating vesicles on part of the oral mucosa, especially the tongue, gums, and cheeks. Vesicles form on an erythematous base and then rupture, leaving a painful ulcer, followed by a yellowish crust. Other findings include submaxillary lymphadenopathy, increased salivation, halitosis, anorexia, and keratoconjunctivitis.

Herpes zoster. Herpes zoster is a common viral infection that may produce painful vesicles on the buccal mucosa, tongue, uvula, pharynx, and larynx. Small red nodules typically erupt unilaterally around the thorax or vertically on the arms and legs, and rapidly become vesicles filled with clear fluid or pus; vesicles dry and form scabs about 10 days after eruption. A fever and general malaise accompany pruritus, paresthesia or hyperesthesia, and tenderness along the course of the involved sensory nerve.

Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia. Inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia is a painless nodular swelling of the buccal mucosa that typically results from cheek trauma or irritation and is characterized by pink, smooth, pedunculated areas of soft tissue.

Leukoplakia, erythroplakia. Leukoplakia is a white lesion that can’t be removed simply by rubbing the mucosal surface — unlike candidiasis. It may occur in response to chronic irritation from dentures or from tobacco or pipe smoking, or it may represent dysplasia or early squamous cell carcinoma.

Erythroplakia is red and edematous and has a velvety surface. About 90% of all cases of erythroplakia are either dysplasia or cancer.

Pemphigoid (benign mucosal). Pemphigoid is a rare autoimmune disease that’s characterized by thick-walled vesicles on the oral mucous membranes, the conjunctiva and, less commonly, the skin. Mouth lesions typically develop months or even years before other manifestations and may occur as desquamative patchy gingivitis or as a vesicobullous eruption. Secondary fibrous bands may lead to dysphagia, hoarseness, and blindness. Recurrent skin lesions include vesicobullous eruptions, usually on the inguinal area and extremities, and an erythematous, vesicobullous plaque on the scalp and face near the affected mucous membranes.

Pemphigus. Pemphigus is a chronic skin disease that’s characterized by thin-walled vesicles and bullae that appear in cycles on skin or mucous membranes that otherwise appear normal. On the oral mucosa, bullae rupture, leaving painful lesions and raw patches that bleed easily. Associated findings include bullae anywhere on the body, denudation of the skin, and pruritus.

Pyogenic granuloma. Typically the result of injury, trauma, or irritation, pyogenic granuloma

— a soft, tender nodule, papule, or polypoid mass of excessive granulated tissue — usually appears on the gingivae but can also erupt on the lips, tongue, or buccal mucosa. The lesions bleed easily because they contain many capillaries. The affected area may be smooth or have a warty surface; erythema develops in the surrounding mucosa. The lesions may ulcerate, producing a purulent exudate.

Squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinoma is typically a painless ulcer with an elevated, indurated border. It may erupt in areas of leukoplakia and is most common on the lower lip, but it may also occur on the edge of the tongue or floor of the mouth. High-risk factors include chronic smoking and alcohol intake.

Stomatitis (aphthous). Stomatitis, a common disease, is characterized by painful ulcerations of the oral mucosa, usually on the dorsum of the tongue, gingivae, and hard palate.

With recurrent aphthous stomatitis minor, the ulcer begins as one or more erosions covered by a gray membrane and surrounded by a red halo. It’s commonly found on the buccal and lip mucosa and junction, tongue, soft palate, pharynx, gingivae, and all places not bound to the periosteum.

With recurrent aphthous stomatitis major, large, painful ulcers commonly occur on the lips, cheek, tongue, and soft palate; they may last up to 6 weeks and leave a scar.

Syphilis. Primary syphilis typically produces a solitary painless, red ulcer (chancre) on the lip, tongue, palate, tonsil, or gingivae. The ulcer appears as a crater with undulated, raised edges and a shiny center; lip chancres may develop a crust. Similar lesions may appear on the fingers, breasts, or genitals, and regional lymph nodes may become enlarged and tender.

During the secondary stage, multiple painless ulcers covered by a grayish white plaque may erupt on the tongue, gingivae, or buccal mucosa. A macular, papular, pustular, or nodular rash appears, usually on the arms, trunk, palms, soles, face, and scalp; genital lesions usually subside. Other findings include generalized lymphadenopathy, a headache, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, a sore throat, a low-grade fever, metrorrhagia, and postcoital bleeding.

At the tertiary stage, lesions (usually gummas — chronic, painless, superficial nodules or deep granulomatous lesions) develop on the skin and mucous membranes, especially the tongue and

palate.

Systemic lupus erythematosus. Oral lesions are common and appear as erythematous areas associated with edema, petechiae, and superficial ulcers with a red halo and a tendency to bleed. Primary effects include nondeforming arthritis, a butterfly rash across the nose and cheeks, and photosensitivity.

Other Causes

Drugs. Various chemotherapeutic agents can directly produce stomatitis. Also, allergic reactions to penicillin, sulfonamides, gold, quinine, streptomycin, phenytoin, aspirin, and barbiturates commonly cause lesions to develop and erupt. Inhaled steroids used for pulmonary disorders can also cause oral lesions.

Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy may cause oral lesions.

Special Considerations

If the patient’s mouth ulcers are painful, provide a topical anesthetic such as lidocaine.

Patient Counseling

Explain which irritants the patient should avoid and signs and symptoms to report. Teach the patient proper mouth care and oral hygiene.

Pediatric Pointers

Causes of mouth ulcers in children include chickenpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and hand- foot-and-mouth disease. In neonates, mouth ulcers can result from candidiasis or congenital syphilis.

REFERENCES

American Dental Association Survey Center. Survey of dental practice: Income from the private practice of dentistry . Chicago, IL: American Dental Association, 2011.

Selvi, F., & Ozerkan A. G. (2012). Information-seeking patterns of dentists in Istanbul, Turkey. Journal of Dental Education, 66(8), 977–980.

Murmurs

Murmurs are auscultatory sounds heard within the heart chambers or major arteries. They’re classified by their timing and duration in the cardiac cycle, auscultatory location, loudness, configuration, pitch, and quality.

Timing can be characterized as systolic (between S1 and S2), holosystolic (continuous throughout systole), diastolic (between S2 and S1), or continuous throughout systole and diastole; systolic and diastolic murmurs can be further characterized as early, middle, or late.

Location refers to the area of maximum loudness, such as the apex, the lower left sternal border, or an intercostal space. Loudness is graded on a scale of 1 to 6. A grade 1 murmur is very faint, only detected after careful auscultation. A grade 2 murmur is a soft, evident murmur. Murmurs considered to be grade 3 are moderately loud. A grade 4 murmur is a loud murmur with a possible intermittent

thrill. Grade 5 murmurs are loud and associated with a palpable precordial thrill. Grade 6 murmurs are loud and, like grade 5 murmurs, are associated with a thrill. A grade 6 murmur is audible even when the stethoscope is lifted from the thoracic wall.

Configuration, or shape, refers to the nature of loudness — crescendo (grows louder), decrescendo (grows softer), crescendo-decrescendo (first rises, then falls), decrescendo-crescendo (first falls, then rises), plateau (even intensity), or variable (uneven intensity). The murmur’s pitch may be high or low. Its quality may be described as harsh, rumbling, blowing, scratching, buzzing, musical, or squeaking.

Murmurs can reflect accelerated blood flow through normal or abnormal valves; forward blood flow through a narrowed or irregular valve or into a dilated vessel; blood backflow through an incompetent valve, septal defect, or patent ductus arteriosus; or decreased blood viscosity. Commonly the result of organic heart disease, murmurs occasionally may signal an emergency situation — for example, a loud holosystolic murmur after an acute myocardial infarction (MI) may signal papillary muscle rupture or a ventricular septal defect. Murmurs may also result from surgical implantation of a prosthetic valve. (See When Murmurs Mean Emergency.)

Some murmurs are innocent, or functional. An innocent systolic murmur is generally soft, medium-pitched, and loudest along the left sternal border at the second or third intercostal space. It’s exacerbated by physical activity, excitement, a fever, pregnancy, anemia, or thyrotoxicosis. Examples include Still’s murmur in children and mammary souffle, commonly heard over either breast during late pregnancy and early postpartum. (See Detecting Congenital Murmurs, pages 473 and 474.)

History and Physical Examination

If you discover a murmur, try to determine its type through careful auscultation. (See Identifying Common Murmurs, page 475.) Use the bell of your stethoscope for low-pitched murmurs and the diaphragm for high-pitched murmurs.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

When Murmurs Mean Emergency

Although not normally a sign of an emergency, murmurs — especially newly developed ones

— may signal a serious complication in patients with bacterial endocarditis or a recent acute myocardial infarction (MI).

When caring for a patient with known or suspected bacterial endocarditis, carefully auscultate for new murmurs. Their development, along with crackles, jugular vein distention, orthopnea, and dyspnea, may signal heart failure.

Regular auscultation is also important in a patient who has experienced an acute MI. A loud decrescendo holosystolic murmur at the apex that radiates to the axilla and left sternal border or throughout the chest is significant, particularly in association with a widely split S2 and an atrial gallop (S4). This murmur, when accompanied by signs of acute pulmonary edema, usually indicates the development of acute mitral regurgitation due to rupture of the chordae tendineae

— a medical emergency.

Next, obtain a patient history. Ask if the murmur is a new discovery or if it has been known since birth or childhood. Find out if the patient has experienced associated symptoms, particularly palpitations, dizziness, syncope, chest pain, dyspnea, and fatigue. Explore the patient’s medical history, noting especially an incidence of rheumatic fever, heart disease, or heart surgery, particularly prosthetic valve replacement.

Perform a systematic physical examination. Note especially the presence of cardiac arrhythmias, jugular vein distention, and such pulmonary signs and symptoms as dyspnea, orthopnea, and crackles. Is the patient’s liver tender or palpable? Does he have peripheral edema?

Medical Causes

Aortic insufficiency. Acute aortic insufficiency typically produces a soft, short diastolic murmur over the left sternal border that’s best heard when the patient sits and leans forward and at the end of a forced held expiration. S2 may be soft or absent. Sometimes, a soft, short midsystolic murmur may also be heard over the second right intercostal space. Associated findings include tachycardia, dyspnea, jugular vein distention, crackles, increased fatigue, and pale, cool extremities.

Chronic aortic insufficiency causes a high-pitched, blowing, decrescendo diastolic murmur that’s best heard over the second or third right intercostal space or the left sternal border with the patient sitting, leaning forward, and holding his breath after deep expiration. An Austin Flint murmur — a rumbling, mid-to-late diastolic murmur best heard at the apex — may also occur. Complications may not develop until the patient is between ages 40 to 50; then, typical findings include palpitations, tachycardia, angina, increased fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, and crackles.

Aortic stenosis. With aortic stenosis, the murmur is systolic, beginning after S1 and ending at or before aortic valve closure. It’s harsh and grating, medium pitched, and crescendo-decrescendo. Loudest over the second right intercostal space when the patient is sitting and leaning forward, this murmur may also be heard at the apex, at the suprasternal notch (Erb’s point), and over the carotid arteries.

If the patient has advanced disease, S2 may be heard as a single sound, with inaudible aortic closure. An early systolic ejection click at the apex is typical but is absent when the valve is severely calcified. Associated signs and symptoms usually don’t appear until age 30 in congenital aortic stenosis, ages 30 to 65 in stenosis due to rheumatic disease, and after age 65 in calcific aortic stenosis. They may include dizziness, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, fatigue, and angina.

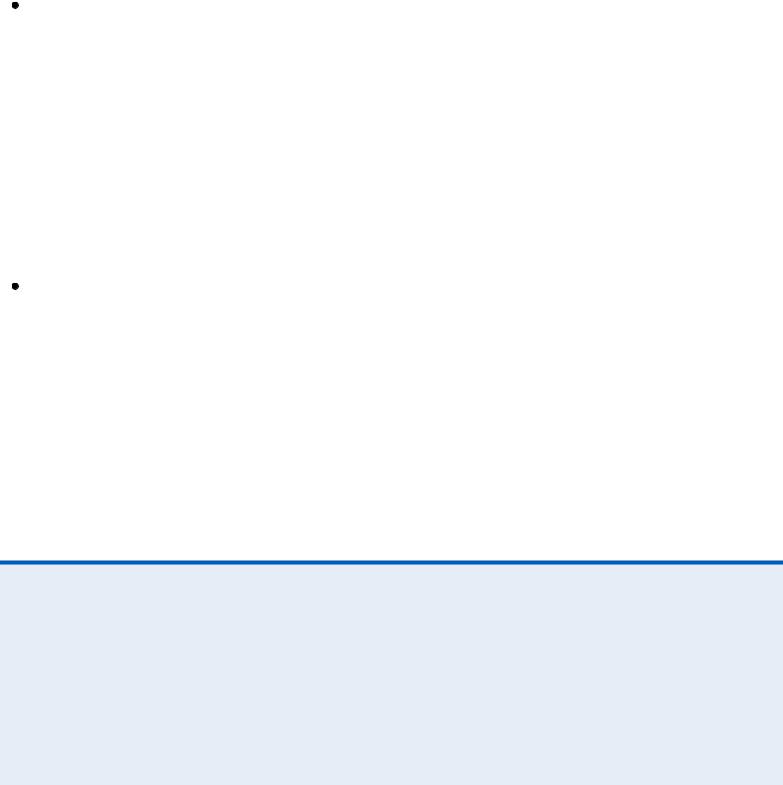

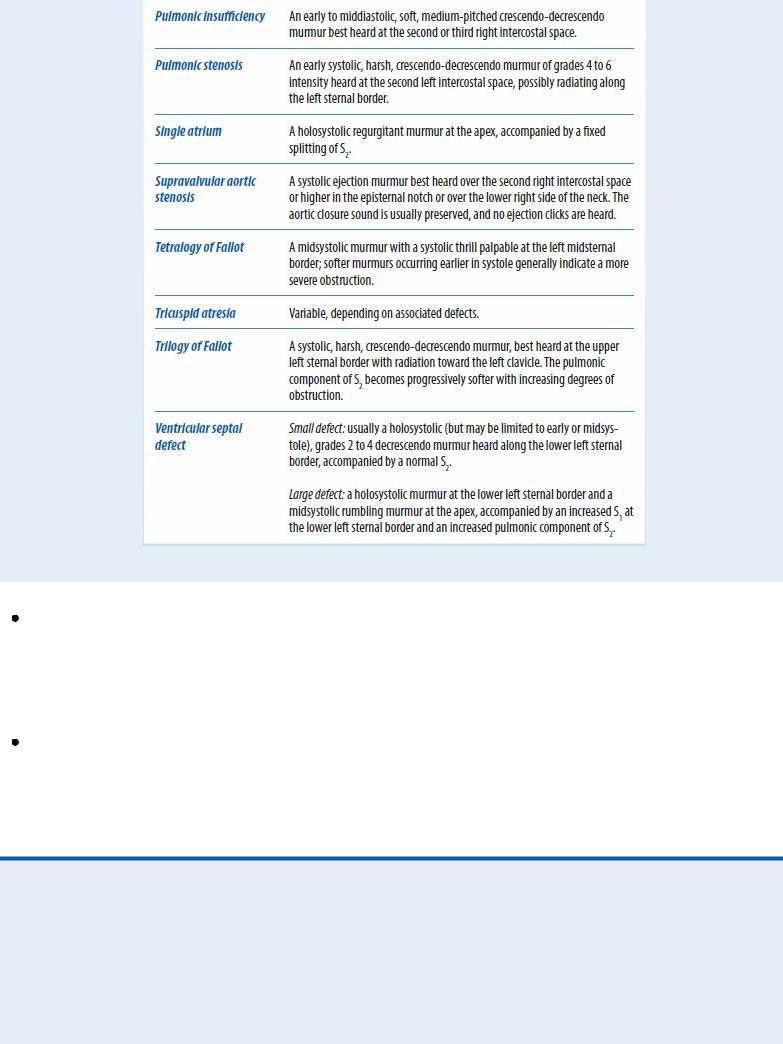

Detecting Congenital Murmurs

Cardiomyopathy (hypertrophic). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy generates a harsh late systolic murmur, ending at S2. Best heard over the left sternal border and at the apex, the murmur is commonly accompanied by an audible S3 or S4. The murmur decreases with squatting and increases with sitting down. Major associated symptoms are dyspnea and chest pain; palpitations, dizziness, and syncope may also occur.

Mitral insufficiency. Acute mitral insufficiency is characterized by a medium-pitched blowing, early systolic or holosystolic decrescendo murmur at the apex, along with a widely split S2 and commonly an S4. This murmur doesn’t get louder on inspiration as with tricuspid insufficiency. Associated findings typically include tachycardia and signs of acute pulmonary edema.

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Common Murmurs

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Common Murmurs

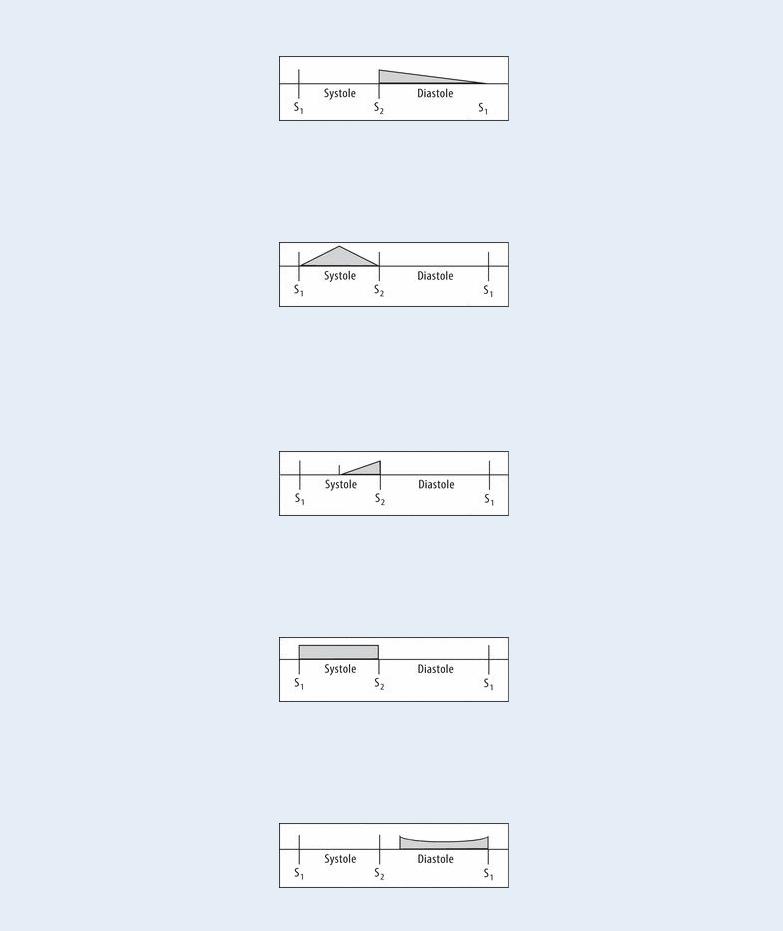

The timing and configuration of a murmur can help you identify its underlying cause. Learn to recognize the characteristics of these common murmurs.

AORTIC INSUFFICIENCY (CHRONIC)

Thickened valve leaflets fail to close correctly, permitting blood backflow into the left ventricle.

AORTIC STENOSIS

Thickened, scarred, or calcified valve leaflets impede ventricular systolic ejection.

MITRAL PROLAPSE

An incompetent mitral valve bulges into the left atrium because of an enlarged posterior leaflet and elongated chordae tendineae.

MITRAL INSUFFICIENCY (CHRONIC)

Incomplete mitral valve closure permits backflow of blood into the left atrium.

MITRAL STENOSIS

Thickened or scarred valve leaflets cause valve stenosis and restrict blood flow.

Chronic mitral insufficiency produces a high-pitched, blowing, holosystolic plateau murmur that’s loudest at the apex and usually radiates to the axilla or back. Fatigue, dyspnea, and palpitations may also occur.

Mitral prolapse. Mitral prolapse generates a midsystolic to late-systolic click with a highpitched late-systolic crescendo murmur, best heard at the apex. Occasionally, multiple clicks may be heard, with or without a systolic murmur. Associated findings include cardiac awareness, migraine headaches, dizziness, weakness, syncope, palpitations, chest pain, dyspnea, severe episodic fatigue, mood swings, and anxiety.

Mitral stenosis. With mitral stenosis, the murmur is soft, low-pitched, rumbling, crescendodecrescendo, and diastolic, accompanied by a loud S1 or an opening snap — a cardinal sign. It’s best heard at the apex with the patient in the left lateral position. Mild exercise helps make this murmur audible.

With severe stenosis, the murmur of mitral regurgitation may also be heard. Other findings include hemoptysis, exertional dyspnea and fatigue, and signs of acute pulmonary edema. Myxomas. A left atrial myxoma (most common) usually produces a middiastolic murmur and a holosystolic murmur that’s loudest at the apex, with an S4, an early diastolic thudding sound (tumor plop), and a loud, widely split S1. Related features include dyspnea, orthopnea, chest pain, fatigue, weight loss, and syncope.

A right atrial myxoma causes a late diastolic rumbling murmur, a holosystolic crescendo murmur, and tumor plop, best heard at the lower left sternal border. Other findings include fatigue, peripheral edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly.

A left ventricular myxoma (rare) produces a systolic murmur, best heard at the lower left sternal border; arrhythmias; dyspnea; and syncope.

A right ventricular myxoma commonly generates a systolic ejection murmur with delayed S2 and a tumor plop, best heard at the left sternal border. It’s accompanied by peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, ascites, dyspnea, and syncope.

Papillary muscle rupture. With papillary muscle rupture — a life-threatening complication of an acute MI — a loud holosystolic murmur can be auscultated at the apex. Related findings include severe dyspnea, chest pain, syncope, hemoptysis, tachycardia, and hypotension.

Rheumatic fever with pericarditis. A pericardial friction rub along with murmurs and gallops are heard best with the patient leaning forward on his hands and knees during forced expiration. The most common murmurs heard are the systolic murmur of mitral regurgitation, a midsystolic murmur due to swelling of the mitral valve leaflet, and the diastolic murmur of aortic regurgitation. Other signs and symptoms include a fever, joint and sternal pain, edema, and tachypnea.

Tricuspid insufficiency. Tricuspid insufficiency is a valvular abnormality that’s characterized by a soft, high-pitched, holosystolic blowing murmur that increases with inspiration (Carvallo’s sign), decreases with exhalation and Valsalva’s maneuver, and is best heard over the lower left sternal border and the xiphoid area. Following a lengthy asymptomatic period, exertional dyspnea and orthopnea may develop, along with jugular vein distention, ascites, peripheral cyanosis and edema, muscle wasting, fatigue, weakness, and syncope.

Tricuspid stenosis. Tricuspid stenosis is a valvular disorder that produces a diastolic murmur similar to that of mitral stenosis, but louder with inspiration and decreased with exhalation and Valsalva’s maneuver. S 1 may also be louder. Associated signs and symptoms include fatigue, syncope, peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, ascites, hepatomegaly, and dyspnea.