Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Lymphadenopathy

Lymphadenopathy — enlargement of one or more lymph nodes — may result from increased production of lymphocytes or reticuloendothelial cells or from infiltration of cells that aren’t normally present. This sign may be generalized (involving three or more node groups) or localized. Generalized lymphadenopathy may be caused by an inflammatory process, such as bacterial or viral infection, connective tissue disease, an endocrine disorder, or neoplasm. Localized lymphadenopathy most commonly results from infection or trauma affecting a specific area. (See Areas of Localized Lymphadenopathy. Also see Causes of Localized Lymphadenopathy, page 452.)

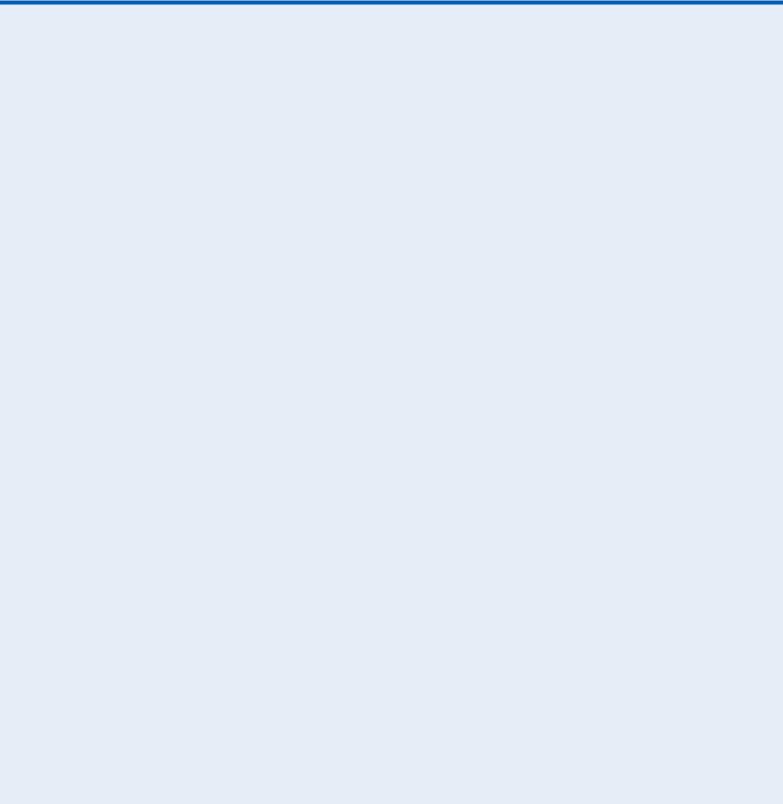

Areas of Localized Lymphadenopathy

When you detect an enlarged lymph node, palpate the entire lymph node system to determine the extent of lymphadenopathy. Include the lymph nodes indicated here in your assessment.

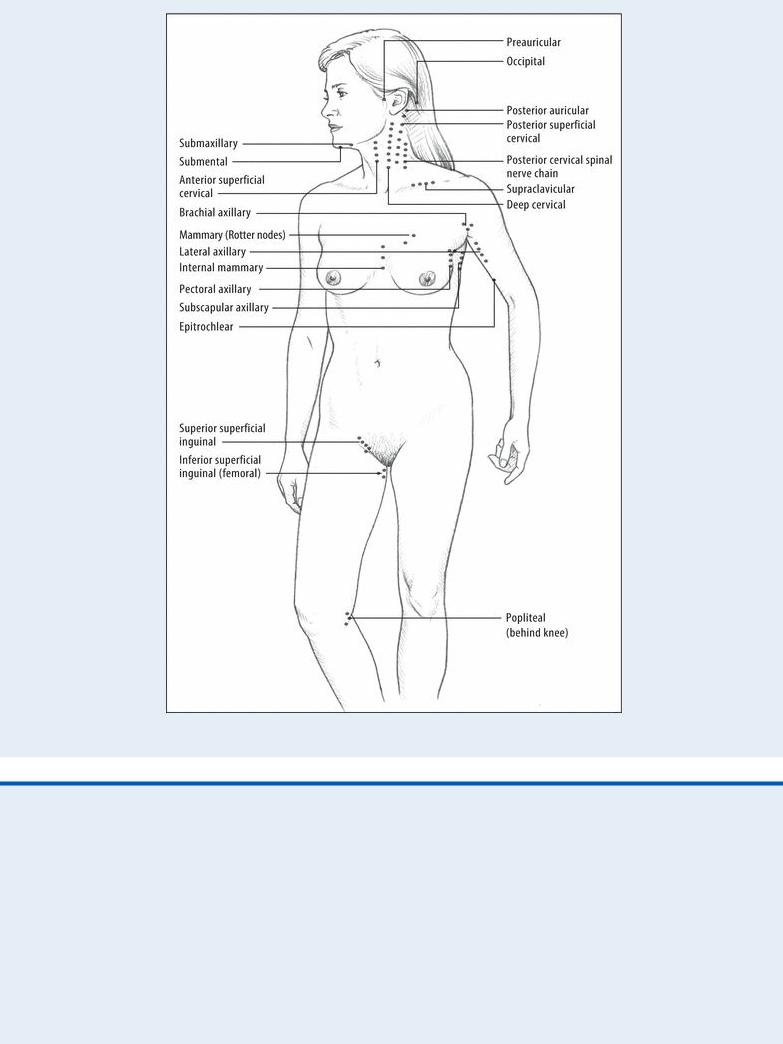

Causes of Localized Lymphadenopathy

Various disorders can cause localized lymphadenopathy, but this sign usually results from infection or trauma affecting the specific area. Here you‘ll find some common causes of lymphadenopathy listed according to the areas affected.

Normally, lymph nodes are discrete, mobile, soft, nontender and, except in children, nonpalpable. (However, palpable nodes may be normal in adults.) Nodes that are more than ⅜″ (1 cm) in diameter are cause for concern. They may be tender, and the skin overlying the lymph node may be erythematous, suggesting a draining lesion. Alternatively, they may be hard and fixed, tender or nontender, suggesting a malignant tumor.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when he first noticed the swelling and whether it’s located on one side of his body or both. Are the swollen areas sore, hard, or red? Ask the patient if he has recently had an infection or other health problem. Also ask if a biopsy has ever been done on any node because this may indicate a previously diagnosed cancer. Find out if the patient has a family history of cancer.

Palpate the entire lymph node system to determine the extent of lymphadenopathy and to detect other areas of local enlargement. Use the pads of your index and middle fingers to move the skin over underlying tissues at the nodal area. If you detect enlarged nodes, note their size in centimeters and whether they’re fixed or mobile, tender or nontender, and erythematous or not. Note their texture: Is the node discrete, or does the area feel matted? If you detect tender, erythematous lymph nodes, check the area drained by that part of the lymph system for signs of infection, such as erythema and swelling. Also, palpate for and percuss the spleen.

Medical Causes

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Besides lymphadenopathy, findings include a history of fatigue, night sweats, afternoon fevers, diarrhea, weight loss, and a cough with several concurrent infections appearing soon afterward.

Anthrax (cutaneous). Lymphadenopathy, malaise, a headache, and a fever may develop along with a lesion that progresses into a painless, necrotic-centered ulcer.

Brucellosis. Generalized lymphadenopathy usually affects cervical and axillary lymph nodes, making them tender. Brucellosis usually begins insidiously with easy fatigability, malaise, headache, backache, anorexia, weight loss, and arthralgia; it may also begin abruptly with chills, a fever that usually rises in the morning and subsides during the day, and diaphoresis.

Cytomegalovirus infection. Generalized lymphadenopathy occurs in the immunocompromised patient and is accompanied by a fever, malaise, a rash, and hepatosplenomegaly.

Hodgkin’s disease. The extent of lymphadenopathy reflects the stage of malignancy — from stage I involvement of a single lymph node region to stage IV generalized lymphadenopathy. Common early signs and symptoms include pruritus and, in older patients, fatigue, weakness, night sweats, malaise, weight loss, and an unexplained fever (usually to 101°F [38.3°C]). Also, if mediastinal lymph nodes enlarge, tracheal and esophageal pressure produces dyspnea and dysphagia.

Kawasaki disease or syndrome. This disease is also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome because it characteristically involves swelling of the lymph nodes, particularly those in the neck. Other symptoms include high fever that lasts 5 days or longer, rash, swelling of the hands and feet, nondraining conjunctivitis, bright red cracked lips, a strawberry tongue, peeling skin on the fingertips and toes, and a rash on the trunk and genitals. More serious complications involve damage to the heart and the blood vessels that supply the heart. I.V. immunoglobulin and aspirin are the standard treatment.

Leptospirosis. Lymphadenopathy occurs infrequently in leptospirosis, a rare disease. More common findings include a sudden onset of a fever and chills, malaise, myalgia, a headache, nausea and vomiting, and abdominal pain.

Leukemia (acute lymphocytic). Generalized lymphadenopathy is accompanied by fatigue, malaise, pallor, and a low-grade fever. The patient also experiences prolonged bleeding time, swollen gums, weight loss, bone or joint pain, and hepatosplenomegaly.

Leukemia (chronic lymphocytic). Generalized lymphadenopathy appears early, along with fatigue, malaise, and a fever. As the disease progresses, hepatosplenomegaly, severe fatigue, and weight loss occur. Other late findings include bone tenderness, edema, pallor, dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, bleeding, anemia, and macular or nodular lesions.

Lyme’s disease. Spread by the bite of certain ticks, Lyme’s disease begins with a skin lesion called erythema chronicum migrans. As the disease progresses, the patient may suffer from lymphadenopathy, constant malaise and fatigue, and an intermittent headache, a fever, chills, and aches. He may go on to develop arthralgia and, eventually, neurologic and cardiac abnormalities.

Monkey pox. Patients infected with the monkeypox virus will have lymph node swelling approximately 12 days after becoming infected. Other symptoms include fever, conjunctivitis, cough, shortness of breath, headache, muscle aches, backache, general feeling of discomfort and exhaustion, and rash. Treatment should focus on relieving symptoms.

Mononucleosis (infectious). Characteristic, painful lymphadenopathy involves cervical,

axillary, and inguinal nodes. Posterior cervical adenopathy is also common. Typically, prodromal symptoms — such as a headache, malaise, and fatigue — occur 3 to 5 days before the appearance of the classic triad of lymphadenopathy, sore throat, and temperature fluctuations with an evening peak of about 102°F (38.9°C). Hepatosplenomegaly may develop, along with findings of stomatitis, exudative tonsillitis, or pharyngitis.

Mycosis fungoides. Lymphadenopathy occurs in stage III of mycosis fungoides, a rare, chronic malignant lymphoma. It’s accompanied by ulcerated brownish red tumors that are painful and itchy.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Painless enlargement of one or more peripheral lymph nodes is the most common sign of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, with generalized lymphadenopathy characterizing stage IV. Dyspnea, a cough, and hepatosplenomegaly occur, along with systemic complaints of a fever of up to 101°F (38.37°C), night sweats, fatigue, malaise, and weight loss.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). Signs and symptoms of the bubonic form of plague, a bacterial infection, include lymphadenopathy, a fever, and chills.

Rheumatoid arthritis. Lymphadenopathy is an early, nonspecific finding associated with fatigue, malaise, a continuous low-grade fever, weight loss, and vague arthralgia and myalgia. Later, the patient develops joint tenderness, swelling, and warmth; joint stiffness after inactivity (especially in the morning); and subcutaneous nodules on the elbows. Eventually, joint deformity, muscle weakness, and atrophy may occur.

Sarcoidosis. Generalized, bilateral hilar and right paratracheal forms of lymphadenopathy (seen on chest X-ray) with splenomegaly are common. Initial findings are arthralgia, fatigue, malaise, weight loss, and pulmonary symptoms. Other findings vary with the site and extent of fibrosis. Typical cardiopulmonary findings include breathlessness, a cough, substernal chest pain, and arrhythmias. About 90% of patients have an abnormal chest X-ray at sometime during their illness. Musculoskeletal and cutaneous features may include muscle weakness and pain, phalangeal and nasal mucosal lesions, and subcutaneous skin nodules. Common ophthalmic findings include eye pain, photophobia, and nonreactive pupils. Central nervous system involvement may produce cranial or peripheral nerve palsies and seizures.

Sjögren’s syndrome. Lymphadenopathy of the parotid and submaxillary nodes may occur in Sjögren’s syndrome, a rare disorder. Assessment reveals cardinal signs of dry mouth, eyes, and mucous membranes, which may be accompanied by photosensitivity, poor vision, eye fatigue, nasal crusting, and epistaxis.

Syphilis (secondary). Generalized lymphadenopathy occurs in the second stage and may be accompanied by a macular, papular, pustular, or nodular rash on the arms, trunk, palms, soles, face, and scalp. A palmar rash is a significant diagnostic sign. A headache, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, a sore throat, and a low-grade fever may occur.

Systemic lupus erythematosus. Generalized lymphadenopathy typically accompanies the hallmark butterfly rash, photosensitivity, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and joint pain and stiffness. Pleuritic chest pain and a cough may appear with systemic findings, such as a fever, anorexia, and weight loss.

Tuberculous lymphadenitis. Lymphadenopathy may be generalized or restricted to superficial lymph nodes. Affected lymph nodes may become fluctuant and drain to surrounding tissue. They may be accompanied by a fever, chills, weakness, and fatigue.

Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Lymphadenopathy may appear along with

hepatosplenomegaly. Associated findings include retinal hemorrhage, pallor, and signs of heart failure, such as jugular vein distention and crackles. The patient shows a decreased level of consciousness, abnormal reflexes, and signs of peripheral neuritis. Weakness, fatigue, weight loss, epistaxis, and GI bleeding may also occur. Circulatory impairment occurs because of increased blood viscosity.

Other Causes

Drugs. Phenytoin may cause generalized lymphadenopathy.

Immunizations. Typhoid vaccination may cause generalized lymphadenopathy.

Special Considerations

If the patient has a fever above 101°F (38.3°C), don’t automatically assume that the temperature should be lowered. A patient with a bacterial or viral infection must tolerate the fever, which may assist recovery. Provide an antipyretic if the patient is uncomfortable. Tepid sponge baths or a hypothermia blanket may also be used.

Expect to obtain blood for routine blood work, platelet and white blood cell counts, liver and renal function studies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood cultures. Prepare the patient for other scheduled diagnostic tests, such as chest X-ray, liver and spleen scan, lymph node biopsy, or lymphography, to visualize the lymphatic system. If tests reveal infection, check your facility’s policy regarding infection control and isolation precautions.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient ways to prevent infection. Explain which signs and symptoms of infection the patient should report. Explain the reasons for isolation, as applicable, and stress the importance of a healthy diet and rest.

Pediatric Pointers

Infection is the most common cause of lymphadenopathy in children. The condition is commonly associated with otitis media and pharyngitis.

Provide an antipyretic if the child has a history of febrile seizures.

REFERENCES

Kalungi, S., Wabinga, H., & Bostad, L. (2009). Reactive lymphadenopathy in Ugandan patients and its relationship to EBV and HIV infection. APMIS, 117, 302–307.

Ramos, C. G., & Goldani, L. Z. (2011) . Biopsy of peripheral lymph nodes: A useful tool to diagnose opportunistic diseases in HIVinfected patients. Tropical Doctor, 41, 26–27.

M

McBurney’s Sign

A telltale indicator of localized peritoneal inflammation in acute appendicitis, McBurney’s sign is tenderness elicited by palpating the right lower quadrant over McBurney’s point. McBurney’s point is about 2″ (5 cm) above the anterior superior spine of the ilium, on the line between the spine and the umbilicus where pressure produces pain and tenderness in acute appendicitis. Before McBurney’s sign is elicited, the abdomen is inspected for distention, auscultated for hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, and tested for tympany.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient to describe the abdominal pain. When did it begin? Does coughing, movement, eating, or elimination worsen or help relieve it? Also ask about the development of other signs and symptoms, such as vomiting and a low-grade fever. Ask the patient to point with a finger to the spot where the pain is worst.

Continue light palpation of the patient’s abdomen to detect additional tenderness, rigidity, guarding, or pain. Observe the patient’s facial expression for signs of pain, such as grimacing or wincing. (See Eliciting McBurney’s Sign, page 456.) Auscultate the abdomen, noting decreased bowel sounds.

Medical Causes

Appendicitis. McBurney’s sign appears within the first 2 to 12 hours after the onset of appendicitis, after initial pain in the epigastric and periumbilical area shifts to the right lower quadrant (McBurney’s point). This persistent pain increases with walking or coughing. Nausea and vomiting may occur from the start. Boardlike abdominal rigidity and rebound tenderness that worsen as the condition progresses accompany cutaneous hyperalgesia, a fever, constipation or diarrhea, tachycardia, retractive respirations, anorexia, and moderate malaise.

Rupture of the appendix causes sudden cessation of pain. Then, signs and symptoms of peritonitis develop, such as severe abdominal pain, pallor, hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, diaphoresis, and a high fever.

Special Considerations

Draw blood for laboratory tests such as a complete blood count, including a white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood cultures, and prepare the patient for abdominal X-rays to confirm appendicitis. Make sure that the patient receives nothing by mouth, and expect to prepare the patient for an appendectomy. Administration of a cathartic or an enema may cause the appendix to rupture and should be avoided.

Patient Counseling

Explain which postoperative signs and symptoms the patient should report. Instruct the patient on wound care and explain any needed activity restrictions.

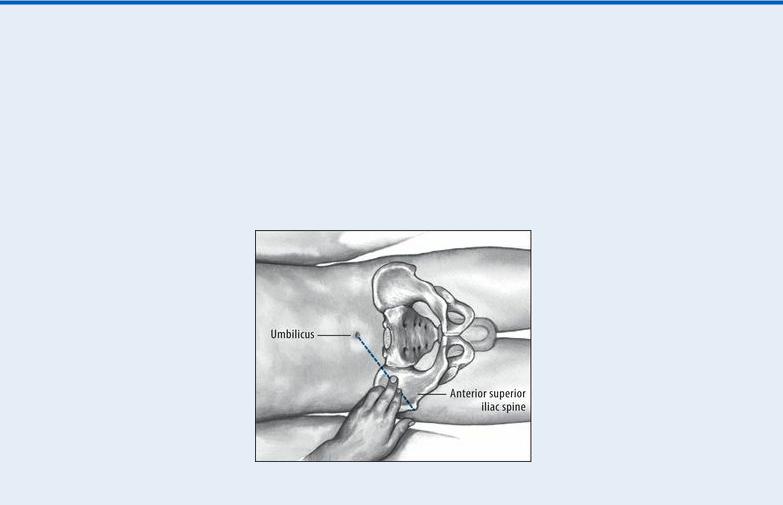

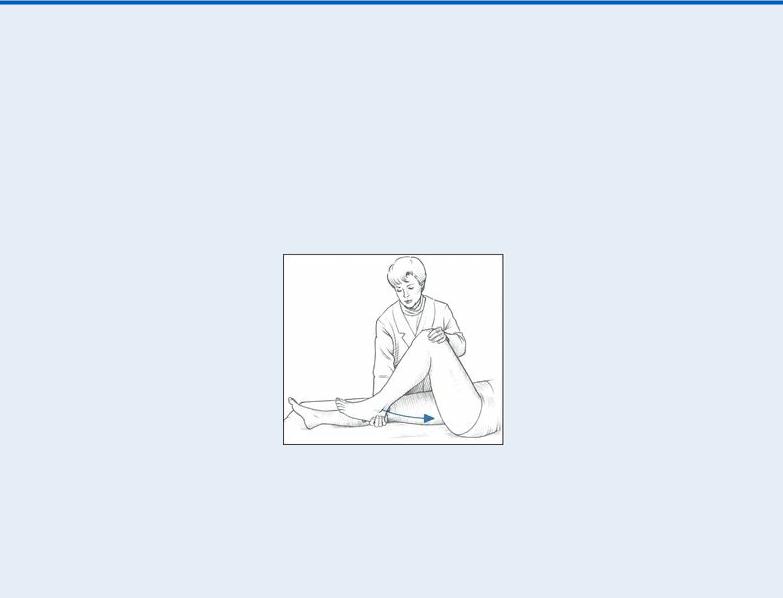

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McBurney’s Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McBurney’s Sign

To elicit McBurney’s sign, help the patient into a supine position, with his knees slightly flexed and his abdominal muscles relaxed. Then, palpate deeply and slowly in the right lower quadrant over McBurney’s point — located about 2″ (5 cm) from the right anterior superior spine of the ilium, on a line between the spine and the umbilicus. Point pain and tenderness, a positive McBurney’s sign, indicates appendicitis.

Pediatric Pointers

McBurney’s sign is also elicited in children with appendicitis.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, McBurney’s sign (as well as other peritoneal signs) may be decreased or absent.

REFERENCES

Ilves, I. , Paajanen, H. E., Herzig, K. H., Fagerstrom, A., & Miettinen, P. J. (2011) . Changing incidence of acute appendicitis and nonspecific abdominal pain between 1987 and 2007 in Finland. World Journal of Surgery, 35(4), 731–738.

Wilms, I. M., De Hoog, D. E., De Visser, D. C. , & Janzing, H. M. (2011) . Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment for acute appendicitis. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 9(11), CD008359.

McMurray’s Sign

Commonly an indicator of medial meniscal injury, McMurray’s sign is a palpable, audible click or pop elicited by rotating the tibia on the femur. It results when gentle manipulation of the leg traps torn

cartilage and then lets it snap free. Because eliciting this sign forces the surface of the tibial plateau against the femoral condyles, such manipulation is contraindicated in patients with suspected fractures of the tibial plateau or femoral condyles.

A positive McMurray’s sign augments other findings commonly associated with meniscal injury, such as severe joint line tenderness, locking or clicking of the joint, and a decreased range of motion (ROM).

History and Physical Examination

After McMurray’s sign has been elicited, find out if the patient is experiencing acute knee pain. Then ask him to describe a recent knee injury. For example, did his injury place twisting external or internal force on the knee, or did he experience blunt knee trauma from a fall? Also, ask about previous knee injury, surgery, prosthetic replacement, or other joint problems, such as arthritis, that could have weakened the knee. Ask if anything aggravates or relieves the pain and if he needs assistance to walk.

Have the patient point to the exact area of pain. Assess the leg’s ROM, both passive and with resistance. Next, check for cruciate ligament stability by noting anterior or posterior movement of the tibia on the femur (drawer sign). Finally, measure the quadriceps muscles in both legs for symmetry. (See Eliciting McMurray’s Sign.)

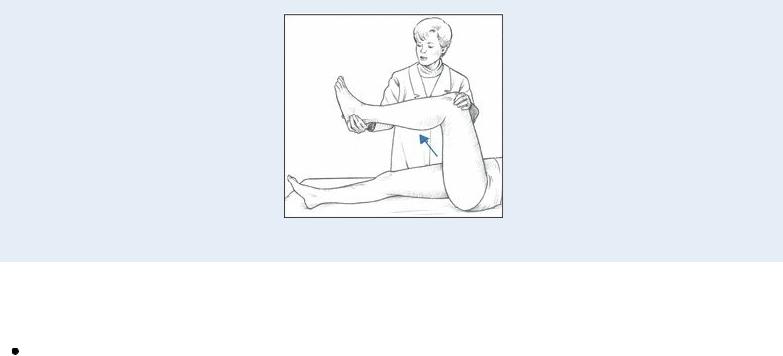

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McMurray’s Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McMurray’s Sign

Eliciting McMurray’s sign requires special training and gentle manipulation of the patient’s leg to avoid extending a meniscal tear or locking the knee. If you’ve been trained to elicit McMurray’s sign, place the patient in a supine position and flex his affected knee until his heel nearly touches his buttock. Place your thumb and index finger on either side of the knee joint space and grasp his heel with your other hand. Then rotate the foot and lower leg laterally to test the posterior aspect of the medial meniscus.

Keeping the patient’s foot in a lateral position, extend the knee to a 90-degree angle to test the anterior aspect of the medial meniscus. A palpable or audible click — a positive McMurray’s sign — indicates injury to meniscal structures.

Medical Causes

Meniscal tear. McMurray’s sign can usually be elicited with a meniscal tear injury. Associated signs and symptoms include acute knee pain at the medial or lateral joint line (depending on injury site) and decreased ROM or locking of the knee joint. Quadriceps weakening and atrophy may also occur.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for knee X-rays, arthroscopy, and arthrography, and obtain any previous X-rays for comparison. If trauma precipitated the knee pain and McMurray’s sign, an effusion or hemarthrosis may occur. Prepare the patient for aspiration of the joint. Immobilize and apply ice to the knee, and apply a cast or a knee immobilizer.

Patient Counseling

Explain the purpose of elevating the affected leg, the proper use of any required assistive devices, and the proper use of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. Teach knee exercises and discuss any lifestyle changes the patient should make.

Pediatric Pointers

McMurray’s sign in adolescents is usually elicited in a meniscal tear caused by a sports injury. It may also be elicited in children with congenital discoid meniscus.

REFERENCES

Amorim, J. A., Remigio, D. S., Damazio Filho, O., Barros, M. A., Carvalho, V. N. , & Valenca, M. M. (2010) . Intracranial subdural hematoma post-spinal anesthesia: Report of two cases and review of 33 cases in the literature. Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology, 60, 620–629.

Machurot, P. Y. , Vergnion, M . , Fraipont, V. , Bonhomme, V., & Damas, F. (2010) . Intracranial subdural hematoma following spinal anesthesia: Case report and review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiology Belgium, 61, 63–66.

Melena