Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Adrenal crisis. A decreased LOC, ranging from lethargy to coma, may develop within 8 to 12 hours of its onset. Early associated findings include progressive weakness, irritability, anorexia, a headache, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and a fever. Later signs and symptoms include hypotension; a rapid, thready pulse; oliguria; cool, clammy skin; and flaccid extremities. The patient with chronic adrenocortical hypofunction may have hyperpigmented skin and mucous membranes.

Brain abscess. A decreased LOC varies from drowsiness to deep stupor, depending on the abscess size and site. Early signs and symptoms — a constant intractable headache, nausea, vomiting, and seizures — reflect increasing ICP. Typical later features include ocular disturbances (nystagmus, vision loss, and pupillary inequality) and signs of infection such as a fever. Other findings may include personality changes, confusion, abnormal behavior, dizziness, facial weakness, aphasia, ataxia, tremor, and hemiparesis.

Brain tumor. The patient’s LOC decreases slowly, from lethargy to coma. He may also experience apathy, behavior changes, memory loss, a decreased attention span, a morning headache, dizziness, vision loss, ataxia, and sensorimotor disturbances. Aphasia and seizures are possible, along with signs of hormonal imbalance, such as fluid retention or amenorrhea. Signs and symptoms vary according to the location and size of the tumor. In later stages, papilledema, vomiting, bradycardia, and a widening pulse pressure also appear. In the final stages, the patient may exhibit decorticate or decerebrate posture.

Cerebral aneurysm (ruptured). Somnolence, confusion and, at times, stupor characterize a moderate bleed; deep coma occurs with severe bleeding, which can be fatal. The onset is usually abrupt, with a sudden, severe headache and nausea and vomiting. Nuchal rigidity, back and leg pain, a fever, restlessness, irritability, occasional seizures, and blurred vision point to meningeal irritation. The type and severity of other findings vary with the site and severity of the hemorrhage and may include hemiparesis, hemisensory defects, dysphagia, and visual defects.

Diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis produces a rapid decrease in the patient’s LOC, ranging from lethargy to coma, commonly preceded by polydipsia, polyphagia, and polyuria. The patient may complain of weakness, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. He may also exhibit orthostatic hypotension; a fruity breath odor; Kussmaul’s respirations; warm, dry skin; and a rapid, thready pulse. Untreated, this condition invariably leads to coma and death.

Encephalitis. Within 24 to 48 hours after onset, the patient may develop changes in his LOC ranging from lethargy to coma. Other possible findings include an abrupt onset of a fever, a headache, nuchal rigidity, nausea, vomiting, irritability, personality changes, seizures, aphasia, ataxia, hemiparesis, nystagmus, photophobia, myoclonus, and cranial nerve palsies.

Encephalomyelitis (postvaccinal). Postvaccinal encephalomyelitis is a life-threatening disorder that produces rapid deterioration in the patient’s LOC, from drowsiness to coma. He also experiences a rapid onset of a fever, a headache, nuchal rigidity, back pain, vomiting, and seizures.

Encephalopathy. With hepatic encephalopathy, signs and symptoms develop in four stages: in the prodromal stage, slight personality changes (disorientation, forgetfulness, slurred speech) and slight tremor; in the impending stage, tremor progressing to asterixis (the hallmark of hepatic encephalopathy), lethargy, aberrant behavior, and apraxia; in the stuporous stage, stupor and hyperventilation, with the patient noisy and abusive when aroused; in the comatose stage, coma with decerebrate posture, hyperactive reflexes, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and fetor hepaticus.

With life-threatening hypertensive encephalopathy, the LOC progressively decreases from lethargy to stupor to coma. Besides markedly elevated blood pressure, the patient may experience a severe headache, vomiting, seizures, vision disturbances, transient paralysis and, eventually, Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

With hypoglycemic encephalopathy, the patient’s LOC rapidly deteriorates from lethargy to coma. Early signs and symptoms include nervousness, restlessness, agitation, and confusion; hunger; alternate flushing and cold sweats; and a headache, trembling, and palpitations. Blurred vision progresses to motor weakness, hemiplegia, dilated pupils, pallor, a decreased pulse rate, shallow respirations, and seizures. Flaccidity and decerebrate posture appear late.

Depending on its severity, hypoxic encephalopathy produces a sudden or gradual decrease in the LOC, leading to coma and brain death. Early on, the patient appears confused and restless, with cyanosis and increased heart and respiratory rates and blood pressure. Later, his respiratory pattern becomes abnormal, and assessment reveals a decreased pulse, blood pressure, and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs); a positive Babinski’s reflex; an absent doll’s eye sign; and fixed pupils. With uremic encephalopathy, the LOC decreases gradually from lethargy to coma. Early on, the patient may appear apathetic, inattentive, confused, and irritable and may complain of a headache, nausea, fatigue, and anorexia. Other findings include vomiting, tremors, edema, papilledema, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, crackles, oliguria, and Kussmaul’s and Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

Heatstroke. As body temperature increases, the patient’s LOC gradually decreases from lethargy to coma. Early signs and symptoms include malaise, tachycardia, tachypnea, orthostatic hypotension, muscle cramps, rigidity, and syncope. The patient may be irritable, anxious, and dizzy and may report a severe headache. At the onset of heatstroke, the patient’s skin is hot, flushed, and diaphoretic with blotchy cyanosis; later, when his fever exceeds 105°F (40.5°C), his skin becomes hot, flushed, and anhidrotic. Pulse and respiratory rate increase markedly, and blood pressure drops precipitously. Other findings include vomiting, diarrhea, dilated pupils, and Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

Hypernatremia. Hypernatremia, life threatening if acute, causes the patient’s LOC to deteriorate from lethargy to coma. He is irritable and exhibits twitches progressing to seizures. Other associated signs and symptoms include a weak, thready pulse; nausea; malaise; a fever; thirst; flushed skin; and dry mucous membranes.

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome. LOC decreases rapidly from lethargy to coma. Early findings include polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, and weakness. Later, the patient may develop hypotension, poor skin turgor, dry skin and mucous membranes, tachycardia, tachypnea, oliguria, and seizures.

Hypokalemia. LOC gradually decreases to lethargy; coma is rare. Other findings include confusion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and polyuria; weakness, decreased reflexes, and malaise; and dizziness, hypotension, arrhythmias, and abnormal electrocardiogram results.

Hyponatremia. Hyponatremia, life threatening if acute, produces a decreased LOC in late stages. Early nausea and malaise may progress to behavior changes, confusion, lethargy, incoordination and, eventually, seizures and coma.

Hypothermia. With severe hypothermia (temperature below 90°F [32.2°C]), the patient’s LOC decreases from lethargy to coma. DTRs disappear, and ventricular fibrillation occurs, possibly followed by cardiopulmonary arrest. With mild to moderate hypothermia, the patient may experience memory loss and slurred speech as well as shivering, weakness, fatigue, and apathy.

Other early signs and symptoms include ataxia, muscle stiffness, and hyperactive DTRs; diuresis; tachycardia and decreased respiratory rate and blood pressure; and cold, pale skin. Later, muscle rigidity and decreased reflexes may develop, along with peripheral cyanosis, bradycardia, arrhythmias, severe hypotension, a decreased respiratory rate with shallow respirations, and oliguria.

Intracerebral hemorrhage. Intracerebral hemorrhage is a life-threatening disorder that produces a rapid, steady loss of consciousness within hours, commonly accompanied by a severe headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Associated signs and symptoms vary and may include increased blood pressure, irregular respirations, a positive Babinski’s reflex, seizures, aphasia, decreased sensations, hemiplegia, decorticate or decerebrate posture, and dilated pupils.

Listeriosis. If listeriosis spreads to the nervous system and causes meningitis, signs and symptoms include a decreased LOC, a fever, a headache, and nuchal rigidity. Early signs and symptoms of listeriosis include a fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Infections during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

Meningitis. Confusion and irritability are expected; however, stupor, coma, and seizures may occur in the patient with severe meningitis. A fever develops early, possibly accompanied by chills. Associated findings include a severe headache, nuchal rigidity, hyperreflexia and, possibly, opisthotonos. The patient exhibits Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs and, possibly, ocular palsies, photophobia, facial weakness, and hearing loss.

Pontine hemorrhage. A sudden, rapid decrease in the patient’s LOC to the point of coma occurs within minutes and death within hours. The patient may also exhibit total paralysis, decerebrate posture, a positive Babinski’s reflex, an absent doll’s eye sign, and bilateral miosis (however, the pupils remain reactive to light).

Seizure disorders. A complex partial seizure produces a decreased LOC, manifested as a blank stare, purposeless behavior (picking at clothing, wandering, lip smacking, or chewing motions), and unintelligible speech. The seizure may be heralded by an aura and followed by several minutes of mental confusion.

An absence seizure usually involves a brief change in the patient’s LOC, indicated by blinking or eye rolling, a blank stare, and slight mouth movements.

A generalized tonic-clonic seizure typically begins with a loud cry and sudden loss of consciousness. Muscle spasm alternates with relaxation. Tongue biting, incontinence, labored breathing, apnea, and cyanosis may also occur. Consciousness returns after the seizure, but the patient remains confused and may have difficulty talking. He may complain of drowsiness, fatigue, a headache, muscle aching, and weakness and may fall into a deep sleep.

An atonic seizure produces sudden unconsciousness for a few seconds.

Status epilepticus, rapidly recurring seizures without intervening periods of physiologic recovery and return of consciousness, can be life threatening.

Shock. A decreased LOC — lethargy progressing to stupor and coma — occurs late in shock. Associated findings include confusion, anxiety, and restlessness; hypotension; tachycardia; a weak pulse with narrowing pulse pressure; dyspnea; oliguria; and cool, clammy skin.

Hypovolemic shock is generally the result of massive or insidious bleeding, either internally or externally. Cardiogenic shock may produce chest pain or arrhythmias and signs of heart failure, such as dyspnea, a cough, edema, jugular vein distention, and weight gain. Septic shock may be accompanied by a high fever and chills. Anaphylactic shock usually involves stridor.

Stroke. Changes in the patient’s LOC vary in degree and onset, depending on the lesion’s size and location and the presence of edema. A thrombotic stroke usually follows multiple transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). Changes in the LOC may be abrupt or take several minutes, hours, or days. An embolic stroke occurs suddenly, and deficits reach their peak almost at once. Deficits associated with a hemorrhagic stroke usually develop over minutes or hours.

Associated findings vary with the stroke type and severity and may include disorientation; intellectual deficits, such as memory loss and poor judgment; personality changes; and emotional lability. Other possible findings include dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, unilateral sensorimotor loss, and vision disturbances. In addition, urine retention, incontinence, constipation, a headache, vomiting, and seizures may occur.

Subdural hemorrhage (acute). Acute subdural hemorrhage is a potentially life-threatening disorder in which agitation and confusion are followed by a progressively decreasing LOC from somnolence to coma. The patient may also experience a headache, a fever, unilateral pupil dilation, decreased pulse and respiratory rates, a widening pulse pressure, seizures, hemiparesis, and a positive Babinski’s reflex.

Thyroid storm. The patient’s LOC decreases suddenly and can progress to coma. Irritability, restlessness, confusion, and psychotic behavior precede the deterioration. Associated signs and symptoms include tremors and weakness; vision disturbances; tachycardia, arrhythmias, angina, and acute respiratory distress; warm, moist, flushed skin; and vomiting, diarrhea, and a fever of up to 105°F (40.5°C).

TIA. The patient’s LOC decreases abruptly (with varying severity) and gradually returns to normal within 24 hours. Site-specific findings may include vision loss, nystagmus, aphasia, dizziness, dysarthria, unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia, tinnitus, paresthesia, dysphagia, or staggering or incoordinated gait.

West Nile encephalitis. West Nile encephalitis is a brain infection that’s caused by the West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne Flavivirus commonly found in Africa, West Asia, and the Middle East and, less commonly, in the United States. Mild infection is common. Signs and symptoms include a fever, a headache, and body aches, commonly with a skin rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe infection is marked by a high fever, a headache, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional convulsions, paralysis and, rarely, death.

Other Causes

Alcohol. Alcohol use causes varying degrees of sedation, irritability, and incoordination; intoxication commonly causes stupor.

Drugs. Sedation and other degrees of a decreased LOC can result from an overdose of a barbiturate, a central nervous system depressant, aspirin, or insulin and other hypoglycemic

medications.

Special Considerations

Reassess the patient’s LOC and neurologic status at least hourly. Carefully monitor ICP and intake and output. Ensure airway patency and proper nutrition. Take precautions to help ensure the patient’s safety. Keep him on bed rest with the side rails up and maintain seizure precautions. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment at the patient’s bedside. Prepare the patient for a computed tomography scan of the head, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, EEG, and lumbar puncture. Elevate the head of the bed to at least 30 degrees. Don’t administer an opioid or sedative because either may further decrease the patient’s LOC and hinder an accurate, meaningful neurologic examination. Apply restraints only if necessary because their use may increase his agitation and confusion. Talk to the patient even if he appears comatose; your voice may help reorient him to reality.

Patient Counseling

Explain the treatments and procedures the patient needs. Teach safety and seizure precautions. Discuss quality-of-life issues. Provide referrals to sources of support.

Pediatric Pointers

The primary cause of a decreased LOC in a child is head trauma, which commonly results from physical abuse or a motor vehicle accident. Other causes include accidental poisoning, hydrocephalus, and meningitis or brain abscess following an ear or respiratory infection. To reduce the parents’ anxiety, include them in the child’s care. Offer them support and realistic explanations of their child’s condition.

REFERENCES

Laureys, S., Celesia, G. G., Cohadon, F., Lavrijsen, J., León-Carrión, J., Sannita, W. G. , … The European Task Force on Disorders of Consciousness. (2010) . Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: A new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome . BMC Medicine, 8, 6–8.

Wilde, E. G., Whiteneck, G. G., Bogner, J. , Bushnik, T. , Cifu, D. X., Dikmen, S., … von Steinbuechel, N., et al. (2010). Recommendations for the use of common outcome measures in traumatic brain injury research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(11), 1650–1660.

Light Flashes [Photopsias]

A cardinal symptom of vision-threatening retinal detachment, light flashes can occur locally or throughout the visual field. The patient usually reports seeing spots, stars, or lightning-type streaks. Flashes can occur suddenly or gradually and can indicate temporary or permanent vision impairment.

In most cases, light flashes signal the splitting of the posterior vitreous membrane into two layers; the inner layer detaches from the retina, and the outer layer remains fixed to it. The sensation of light flashes may result from vitreous traction on the retina, hemorrhage caused by a tear in the retinal capillary, or strands of solid vitreous floating in a local pool of liquid vitreous.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Until retinal detachment is ruled out, restrict the patient's eye and body movement.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when the light flashes began. Can he pinpoint their location, or do they occur throughout the visual field? If the patient is experiencing eye pain or a headache, have him describe it. Ask if the patient wears or has ever worn corrective lenses and if he or a family member has a history of eye or vision problems. Also ask if the patient has other medical problems — especially hypertension or diabetes mellitus, which can cause retinopathy and, possibly, retinal detachment. Obtain an occupational history because light flashes may be related to job stress or eye strain.

Next, perform a complete eye and vision examination, especially if trauma is apparent or suspected. Begin by inspecting the external eye, lids, lashes, and tear puncta for abnormalities and the iris and sclera for signs of bleeding. Observe pupillary size and shape; check for reaction to light, accommodation, and consensual light response. Then test visual acuity in each eye. Also test visual fields; document any light flashes that the patient reports during this test.

Medical Causes

Head trauma. A patient who has sustained minor head trauma may report “seeing stars” when the injury occurs. He may also complain of localized pain at the injury site, a generalized headache, and dizziness. Later, he may develop nausea, vomiting, and a decreased level of consciousness.

Migraine headache. Light flashes — possibly accompanied by an aura — may herald a classic migraine headache. As these symptoms subside, the patient typically experiences a severe, throbbing, unilateral headache that usually lasts 1 to 12 hours and may be accompanied by paresthesia of the lips, face, or hands; slight confusion; dizziness; photophobia; nausea; and vomiting.

Retinal detachment. Light flashes described as floaters or spots are localized in the portion of the visual field where the retina is detaching. With macular involvement, the patient may experience painless vision impairment resembling a curtain covering the visual field.

Vitreous detachment. Visual floaters may accompany a sudden onset of light flashes. Usually, one eye is affected at a time.

Special Considerations

If the patient has retinal detachment, prepare him for surgery and explain postoperative care, including any activity limitations needed until the retina heals completely.

If the patient doesn’t have retinal detachment, reassure him that the light flashes are temporary and don’t indicate eye damage. For the patient with a migraine headache, maintain a quiet, darkened environment; encourage sleep; and administer an analgesic, as ordered.

Patient Counseling

Explain that, after surgery, the patient may need to wear eye patches and adhere to required activity and position restrictions.

Pediatric Pointers

Children may experience light flashes after minor head trauma.

REFERENCES

Arrenberg, A. B., Stainier, D. Y., Baier, H., & Huisken, J. (2010). Optogenetic control of cardiac function. Science, 330, 971–974. Biswas, J. , Krishnakumar, S., & Ahuja, S. (2010) . Manual of ocular pathology. New Delhi, India: Jaypee—Highlights Medical

Publishers.

Chaudhury, D. , Walsh, J. J., Friedman, A. K., Juarez, B. , Ku, S. M., & Koo, J. W. (2013) . Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature, 493, 532–536.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Levin, L. A., & Albert, D. M. (2010). Ocular disease: Mechanisms and management. London: Saunders, Elsevier. Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee—Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

Low Birth Weight

Two groups of neonates are born weighing less than the normal minimum birth weight of 5½ lb (2,500 g) — those who are born prematurely (before 37 weeks’ gestation) and those who are small for gestational age (SGA). Premature neonates weigh an appropriate amount for their gestational age and probably would have matured normally if carried to term. Conversely, SGA neonates weigh less than the normal amount for their age; however, their organs are mature. Differentiating between the two groups helps direct the search for a cause.

In the premature neonate, low birth weight usually results from a disorder that prevents the uterus from retaining the fetus, interferes with the normal course of pregnancy, causes premature separation of the placenta, or stimulates uterine contractions before term. In the SGA neonate, intrauterine growth may be retarded by a disorder that interferes with placental circulation, fetal development, or maternal health. (See Maternal Causes of Low Birth Weight.)

Maternal Causes of Low Birth Weight

If the neonate is small for his gestational age, consider these possible maternal causes:

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Alcohol or opioid abuse

Chronic maternal illness

Cigarette smoking

Hypertension

Hypoxemia

Malnutrition

Toxemia

If the neonate is born prematurely, consider these common maternal causes:

Abruptio placentae

Amnionitis

Cocaine or crack use

Incompetent cervix

Placenta previa

Polyhydramnios

Preeclampsia

Premature rupture of membranes

Severe maternal illness

Regardless of the cause, low birth weight is associated with higher neonate morbidity and mortality; in fact, these neonates are 20 times more likely to die within the first month of life. Low birth weight can also signal a life-threatening emergency.

SGA neonates who will demonstrate catch-up growth do so by 8 to 12 months. Some SGA neonates will remain below the 10th percentile. Weight of the premature neonate should be corrected for gestational age by approximately 24 months.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Because low birth weight may be associated with poorly developed body systems, particularly the respiratory system, your priority is to monitor the neonate's respiratory status. Be alert for signs of distress, such as apnea, grunting respirations, intercostal or xiphoid retractions, or a respiratory rate exceeding 60 breaths/minute after the first hour of life. If you detect any of these signs, prepare to provide respiratory support. Endotracheal intubation or supplemental oxygen with an oxygen hood may be needed.

Monitor the neonate’s axillary temperature. Decreased fat reserves may keep him from maintaining normal body temperature, and a drop below 97.8°F (36.5°C) exacerbates respiratory distress by increasing oxygen consumption. To maintain normal body temperature, use an overbed warmer or an Isolette. (If these are unavailable, use a wrapped rubber bottle filled with warm water, but be careful to avoid hyperthermia.) Cover the neonate’s head to prevent heat loss.

History and Physical Examination

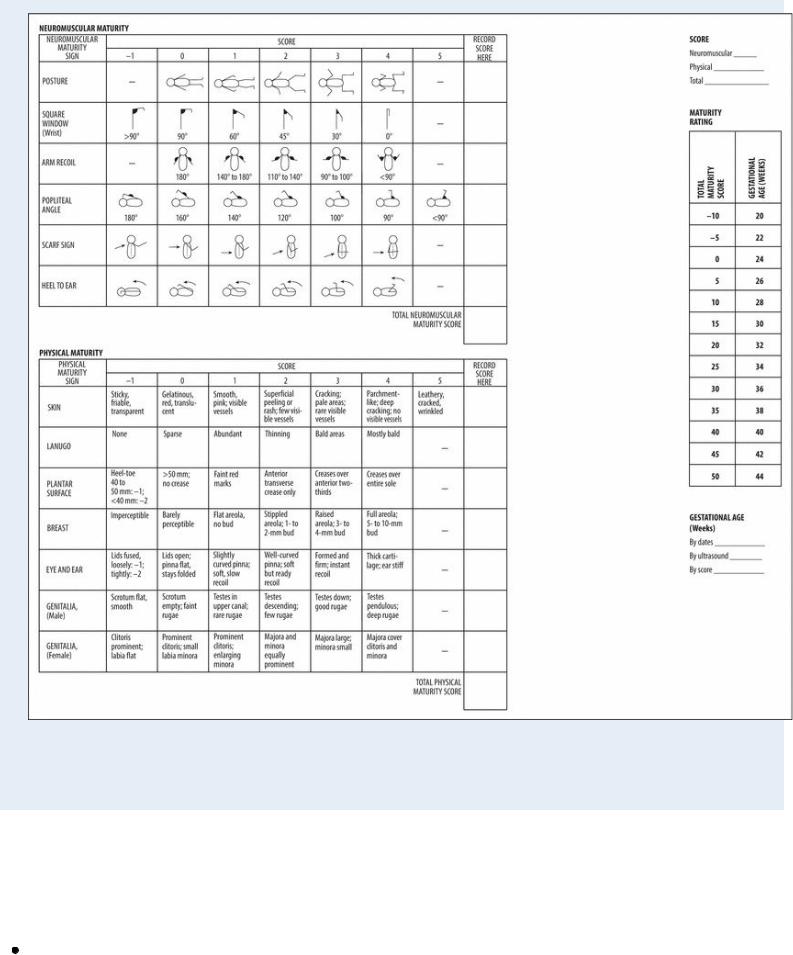

As soon as possible, evaluate the neonate’s neuromuscular and physical maturity to determine gestational age. (See Ballard Scale for Calculating Gestational Age, pages 448 and 449.) Follow with a routine neonatal examination.

Ballard Scale for Calculating Gestational Age

Adapted with permission from Ballard, J. L. (1991) . New Ballard Score expanded to include extremely premature infants. Journal of Pediatrics, 119(3), 417–423.

Medical Causes

This section lists some fetal and placental causes of low birth weight as well as the associated signs and symptoms present in the neonate at birth.

Chromosomal aberrations. Abnormalities in the number, size, or configuration of chromosomes can cause low birth weight and possibly multiple congenital anomalies in a premature or SGA neonate. For example, a neonate with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) may be SGA and have prominent epicanthal folds, a flat-bridged nose, a protruding tongue, palmar

simian creases, muscular hypotonia, and an umbilical hernia.

Cytomegalovirus infection. Although low birth weight in cytomegalovirus infection is usually associated with premature birth, the neonate may be SGA. Assessment at birth may reveal these classic signs: petechiae and ecchymoses, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly, which increases for several days. The neonate may also have a high fever, lymphadenopathy, tachypnea, and dyspnea, along with prolonged bleeding at puncture sites.

Placental dysfunction. Low birth weight and a wasted appearance occur in an SGA neonate. He may be symmetrically short or may appear relatively long for his low weight. Additional findings reflect the underlying cause. For example, if maternal hyperparathyroidism caused placental dysfunction, the neonate may exhibit muscle jerking and twitching, carpopedal spasm, ankle clonus, vomiting, tachycardia, and tachypnea.

Rubella (congenital). Usually, the low birth weight neonate with this congenital rubella is born at term but is SGA. A characteristic “blueberry muffin” rash accompanies cataracts, purpuric lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, and a large anterior fontanel. Abnormal heart sounds, if present, vary with the type of associated congenital heart defect.

Varicella (congenital). Low birth weight is accompanied by cataracts and skin vesicles.

Special Considerations

To make up for low fat and glycogen stores in the low birth weight neonate, initiate feedings as soon as possible and continue to feed him every 2 to 3 hours. Provide gavage or I.V. feeding for the sick or very premature neonate. Check abdominal girth daily or more frequently if indicated, and check stools for blood because increasing girth and bloody stools may indicate necrotizing enterocolitis. A sepsis workup may be necessary if signs of infection are associated with low birth weight.

Check the neonate’s vital signs every 15 minutes for the first hour and at least once every hour thereafter until his condition stabilizes. Be alert for changes in temperature or behavior, feeding problems, respiratory distress, or periods of apnea — possible indications of infection. Also, monitor blood glucose levels and watch for signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia, such as irritability, jitteriness, tremors, seizures, irregular respirations, lethargy, and a high-pitched or weak cry. If the neonate is receiving supplemental oxygen, carefully monitor arterial blood gas values and the oxygen concentration of inspired air to prevent retinopathy.

Monitor the neonate’s urine output by weighing diapers before and after voiding. Check urine color, measure specific gravity, and test for the presence of glucose, blood, or protein. Also, watch for changes in the neonate’s skin color because increasing jaundice may indicate hyperbilirubinemia.

Allow ample time for questions the parents may have.

Patient Counseling

Explain the disorder, procedures, and treatments to the parents. Encourage them to participate in their child’s care to strengthen bonding.

REFERENCES

Gogia, S., & Sachdev, H. S. (2009). Neonatal vitamin A supplementation for prevention of mortality and morbidity in infancy: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal, 338, 919.

Wang, Y. Z. , Ren, W. H. , Liao, W. Q. , & Zhang, G. Y. (2009). Concentrations of antioxidant vitamins in maternal and cord serum and their effect on birth outcomes. Journal of Nutrition Science and Vitaminology, 55(1), 1–8.