Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdfSpecial Considerations

If the patient has cardiac tamponade, prepare him for pericardiocentesis. If he doesn’t have cardiac tamponade, restrict fluids and monitor his intake and output. Insert an indwelling urinary catheter if necessary. If the patient has heart failure, administer a diuretic. Routinely change his position to avoid skin breakdown from peripheral edema. Prepare the patient for central venous or pulmonary artery catheter insertion to measure rightand left-sided heart pressure.

Patient Counseling

Explain which foods and fluids the patient should avoid and what weight gain he should report. Teach him the importance of scheduled rest periods, and help him plan for them. Also teach the patient to weigh himself daily.

Pediatric Pointers

Jugular vein distention is difficult (sometimes impossible) to evaluate in most infants and toddlers because of their short, thick necks. Even in school-age children, measurement of jugular vein distention can be unreliable because the sternal angle may not be the same distance (2″ to 2¾″ [5 to 7 cm]) above the right atrium as it is in adults.

REFERENCES

Nikolaou, M., Parissis, J., Yilmaz, M. B., Seronde, M. F., Kivikko, M., Laribi, S., & Mebazaa, A. (2013). Liver function abnormalities, clinical profile, and outcome in acute decompensated heart failure. European Heart Journal, 34, 742–749.

Raurich, J. M., Llompart-Pou, J. A., Ferreruela, M. , Colomar, A . , Molina, M. , Royo, C., … Ibáñez, J. (2011) . Hypoxic hepatitis in critically ill patients: Incidence, etiology and risk factors for mortality. Journal of Anesthesia, 25, 50–56.

K

Kehr’s Sign

A cardinal sign of hemorrhage within the peritoneal cavity, Kehr’s sign is referred left shoulder pain due to diaphragmatic irritation by intraperitoneal blood. The pain usually arises when the patient assumes the supine position or lowers his head. Such positioning increases the contact of free blood or clots with the left diaphragm, involving the phrenic nerve.

Kehr’s sign usually develops right after the hemorrhage; however, its onset is sometimes delayed up to 48 hours. A classic symptom of a ruptured spleen, Kehr’s sign also occurs in ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

After you detect Kehr’s sign, quickly take the patient’s vital signs. If the patient shows signs of hypovolemia, elevate his feet 30 degrees. In addition, insert a large-bore I.V. line for fluid and blood replacement and an indwelling urinary catheter. Begin monitoring intake and output. Draw blood to determine hematocrit, and provide supplemental oxygen.

Inspect the patient’s abdomen for bruises and distention, and palpate for tenderness. Percuss for Ballance’s sign — an indicator of massive perisplenic clotting and free blood in the peritoneal cavity from a ruptured spleen.

Medical Causes

Intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Kehr’s sign usually accompanies intense abdominal pain, abdominal rigidity, and muscle spasm. Other findings vary with the cause of bleeding. Many patients have a history of blunt or penetrating abdominal injuries.

Special Considerations

In anticipation of surgery, withhold oral intake, and prepare the patient for abdominal X-rays, a computed tomography scan, an ultrasound and, possibly, paracentesis, peritoneal lavage, and culdocentesis. Give an analgesic, if needed.

Patient Counseling

Explain all treatments to the patient and discuss any food or fluid restrictions.

Pediatric Pointers

Because a child may have difficulty describing pain, watch for nonverbal clues such as rubbing the

shoulder.

REFERENCES

Khan, S., Muhammad, I., Laabei, F., & Rothwell, J. (2009). An unusual presentation of non-pathological delayed splenic rupture: A case report. Cases Journal, 2, 6450.

Kodikara, S. (2009) . Death due to hemorrhagic shock after delayed rupture of spleen: A rare phenomenon . American Journal of Forensic Medical Pathology, 30, 382–383.

Kernig’s Sign

A reliable early indicator and tool used to diagnose meningeal irritation, Kernig’s sign elicits resistance and hamstring muscle pain when the examiner attempts to extend the knee while the hip and knee are flexed 90 degrees. However, when the patient’s thigh isn’t flexed on the abdomen, he’s usually able to completely extend his leg. (See Eliciting Kernig’s Sign .) This sign is usually elicited in meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage. With these potentially life-threatening disorders, hamstring muscle resistance results from stretching the bloodor exudate-irritated meninges surrounding spinal nerve roots.

Kernig’s sign can also indicate a herniated disk or spinal tumor. With these disorders, sciatic pain results from disk or tumor pressure on spinal nerve roots.

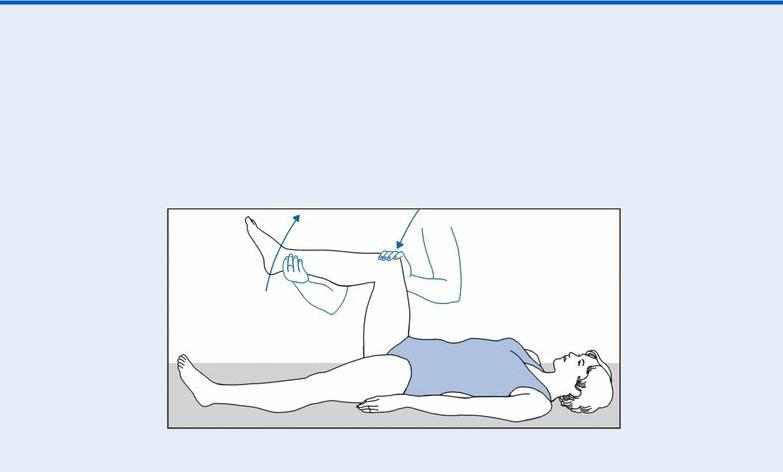

EXAMINATION TIP iciting Kernig’s Sign

EXAMINATION TIP iciting Kernig’s Sign

To elicit Kernig’s sign, place the patient in a supine position. Flex her leg at the hip and knee, as shown here. Then try to extend the leg while you keep the hip flexed. If the patient experiences pain and, possibly, spasm in the hamstring muscle and resists further extension, you can assume that meningeal irritation has occurred.

History and Physical Examination

If you elicit a positive Kernig’s sign and suspect life-threatening meningitis or subarachnoid

hemorrhage, immediately prepare for emergency intervention. (See When Kernig’s Sign Signals CNS Crisis.)

If you don’t suspect meningeal irritation, ask the patient if he feels back pain that radiates down one or both legs. Does he also feel leg numbness, tingling, or weakness? Ask about other signs and symptoms, and find out if he has a history of cancer or back injury. Then perform a physical examination, concentrating on motor and sensory function.

Medical Causes

Lumbosacral herniated disk. A positive Kernig’s sign may be elicited in patients with lumbosacral herniated disk, but the cardinal and earliest feature is sciatic pain on the affected side or on both sides. Associated findings include postural deformity (lumbar lordosis or scoliosis), paresthesia, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes in the involved leg, and dorsiflexor muscle weakness.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

When Kernig’s Sign Signals CNS Crisis

Because Kernig’s sign may signal meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage — life-threatening central nervous system (CNS) disorders — take the patient’s vital signs at once to obtain baseline information. Then test for Brudzinski’s sign to obtain further evidence of meningeal irritation. (See Testing for Brudzinski’s Sign, page 135 .) Next, ask the patient or his family to describe the onset of illness. Typically, the progressive onset of a headache, a fever, nuchal rigidity, and confusion suggests meningitis. Conversely, the sudden onset of a severe headache, nuchal rigidity, photophobia and, possibly, loss of consciousness usually indicates subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Meningitis

If a diagnosis of meningitis is suspected, ask about recent infections, especially tooth abscesses. Ask about exposure to infected persons or places where meningitis is endemic. Meningitis is usually a complication of another bacterial infection, so draw blood for culture studies to determine the causative organism. Prepare the patient for a lumbar puncture (if a tumor or abscess can be ruled out). Also, find out if the patient has a history of I.V. drug abuse, an open head injury, or endocarditis. Insert an I.V. line, and immediately begin administering an antibiotic.

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

If subarachnoid hemorrhage is the suspected diagnosis, ask about a history of hypertension, cerebral aneurysm, head trauma, or arteriovenous malformation. Also ask about sudden withdrawal of an antihypertensive.

Check the patient’s pupils for dilation, and assess him for signs of increasing intracranial

pressure, such as bradycardia, increased systolic blood pressure, and a widened pulse pressure. Insert an I.V. line, and administer supplemental oxygen.

Meningitis. A positive Kernig’s sign usually occurs early with meningitis, along with a fever and, possibly, chills. Other signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation include nuchal rigidity, hyperreflexia, Brudzinski’s sign, and opisthotonos. As intracranial pressure (ICP) increases, headache and vomiting may occur. In severe meningitis, the patient may experience stupor, coma, and seizures. Cranial nerve involvement may produce ocular palsies, facial weakness, deafness, and photophobia. An erythematous maculopapular rash may occur in viral meningitis; a purpuric rash may be seen in those with meningococcal meningitis.

Spinal cord tumor. Kernig’s sign can be elicited occasionally, but the earliest symptom is typically pain felt locally or along the spinal nerve, commonly in the leg. Associated findings include weakness or paralysis distal to the tumor, paresthesia, urine retention, urinary or fecal incontinence, and sexual dysfunction.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs can be elicited within minutes after the initial bleed. The patient experiences a sudden onset of a severe headache that begins in a localized area and then spreads, pupillary inequality, nuchal rigidity, and a decreased level of consciousness. Photophobia, a fever, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and seizures are possible. Focal signs include hemiparesis or hemiplegia, aphasia, and sensory or visual disturbances. Increasing ICP may produce bradycardia, increased blood pressure, respiratory pattern change, and rapid progression to coma.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as a computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, spinal X-ray, myelography, and lumbar puncture. Closely monitor the patient’s vital signs, ICP, and cardiopulmonary and neurologic status. Ensure bed rest, quiet, and minimal stress.

If the patient has a subarachnoid hemorrhage, darken the room and elevate the head of the bed at least 30 degrees to reduce ICP. If he has a herniated disk or spinal tumor, he may require pelvic traction.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient the signs and symptoms of meningitis and how to apply his back brace or cervical collar, as needed. Discuss ways to prevent meningitis. Explain which activities a patient with a herniated disk should avoid.

Pediatric Pointers

Kernig’s sign is considered ominous in children because of their greater potential for rapid deterioration.

REFERENCES

Dalmau, J., Lancaster, E., Martinez-Hernandez, E., Rosenfeld, M. R., & Balice-Gordon, R. (2010). Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Lancet Neurology, 10, 63–74.

Kneen, R., Jakka, S., Mithyantha, R., Riordan, A., & Solomon, T. (2010). The management of infants and children treated with acyclovir for suspected viral encephalitis. Archives of Diseases in Children, 95, 100–106.

L

Leg Pain

Although leg pain commonly signifies a musculoskeletal disorder, it can also result from a more serious vascular or neurologic disorder. The pain may arise suddenly or gradually and may be localized or affect the entire leg. Constant or intermittent, it may feel dull, burning, sharp, shooting, or tingling. Leg pain may affect locomotion, limiting weight bearing. Severe leg pain that follows cast application for a fracture may signal limb-threatening compartment syndrome. The sudden onset of severe leg pain in a patient with underlying vascular insufficiency may signal acute deterioration, possibly requiring an arterial graft or amputation. (See Highlighting Causes of Local Leg Pain, page 436.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has acute leg pain and a history of trauma, quickly take his vital signs and determine the leg’s neurovascular status. Observe the patient’s leg position and check for swelling, gross deformities, or abnormal rotation. Also, be sure to check distal pulses and note skin color and temperature. A pale, cool, and pulseless leg may indicate impaired circulation, which may require emergency surgery.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask him when the pain began and have him describe its intensity, character, and pattern. Is the pain worse in the morning, at night, or with movement? If it doesn’t prevent him from walking, must he rely on a crutch or other assistive device? Also ask him about the presence of other signs and symptoms.

Find out if the patient has a history of leg injury or surgery and if he or a family member has a history of joint, vascular, or back problems. Also ask which medications he’s taking and whether they have helped to relieve his leg pain.

Begin the physical examination by watching the patient walk, if his condition permits. Observe how he holds his leg while standing and sitting. Palpate the legs, buttocks, and lower back to determine the extent of pain and tenderness. If a fracture has been ruled out, test the patient’s range of motion (ROM) in the hip and knee. Also, check reflexes with the patient’s leg straightened and raised, noting action that causes pain. Then compare both legs for symmetry, movement, and active ROM. Additionally, assess sensation and strength. If the patient wears a leg cast, splint, or restrictive dressing, carefully check distal circulation, sensation, and mobility, and stretch his toes to elicit associated pain.

Medical Causes

Bone cancer. Continuous deep or boring pain, commonly worse at night, may be the first symptom of bone cancer. Later, swelling, increased pain with activity, and a palpable lump or mass may occur. The patient may also complain of impaired mobility to the affected limb.

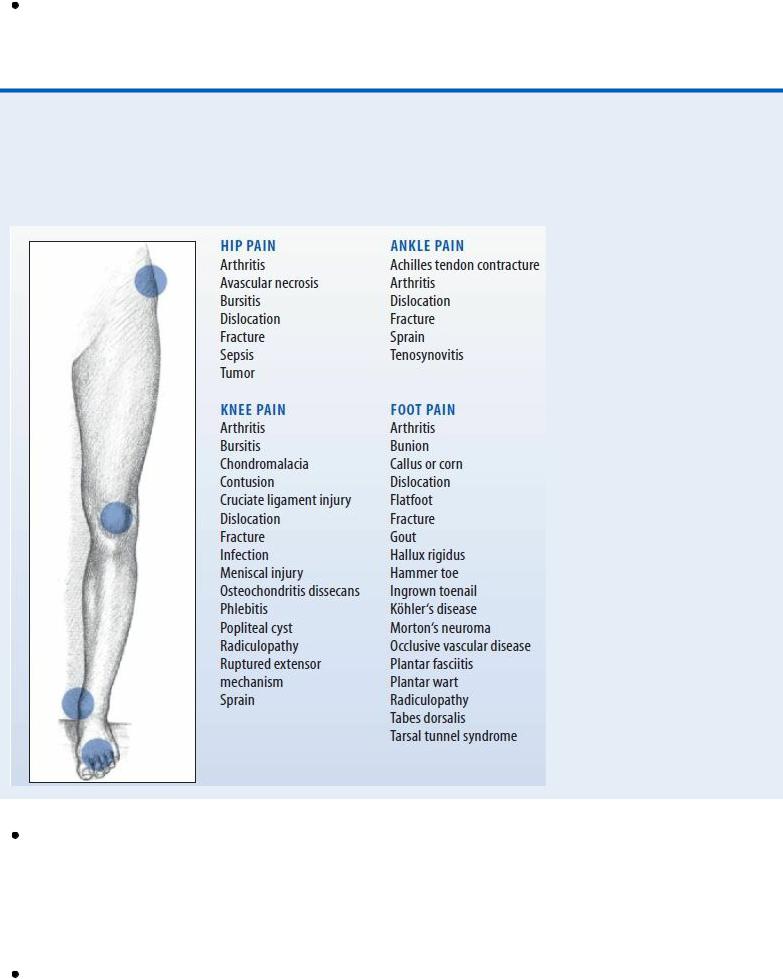

Highlighting Causes of Local Leg Pain

Various disorders cause hip, knee, ankle, or foot pain, which may radiate to surrounding tissues and be reported as leg pain. Local pain is commonly accompanied by tenderness, swelling, and deformity in the affected area.

Compartment syndrome. Progressive, intense lower leg pain that increases with passive muscle stretching is a cardinal sign of compartment syndrome, a limb-threatening disorder. Restrictive dressings or traction may aggravate the pain, which typically worsens despite analgesic administration. Other findings include muscle weakness and paresthesia but apparently normal distal circulation. With irreversible muscle ischemia, paralysis and an absent pulse also occur.

Fracture. Severe, acute pain accompanies swelling and ecchymosis in the affected leg. Movement produces extreme pain, and the leg may be unable to bear weight. Neurovascular status distal to the fracture may be impaired, causing paresthesia, an absent pulse, mottled

cyanosis, and cool skin. Deformity, muscle spasms, and bony crepitation may also occur. Infection. Local leg pain, erythema, swelling, streaking, and warmth characterize soft tissue and bone infections. A fever and tachycardia may be present with other systemic signs.

Occlusive vascular disease. Continuous cramping pain in the legs and feet may worsen with walking, inducing claudication. The patient may report increased pain at night, cold feet, cold intolerance, numbness, and tingling. Examination may reveal ankle and lower leg edema, decreased or absent pulses, and increased capillary refill time. (Normal time is less than 3 seconds.)

Sciatica. Pain, described as shooting, aching, or tingling, radiates down the back of the leg along the sciatic nerve. Typically, activity exacerbates the pain and rest relieves it. The patient may limp to avoid exacerbating the pain and may have difficulty moving from a sitting to a standing position.

Strain or sprain. Acute strain causes sharp, transient pain and rapid swelling, followed by leg tenderness and ecchymosis. Chronic strain produces stiffness, soreness, and generalized leg tenderness several hours after the injury; active and passive motion may be painful or impossible. A sprain causes local pain, especially during joint movement; ecchymosis and, possibly, local swelling and loss of mobility develop.

Thrombophlebitis. Discomfort may range from calf tenderness to severe pain accompanied by swelling, warmth, and a feeling of heaviness in the affected leg. The patient may also develop a fever, chills, malaise, muscle cramps, and a positive Homans’ sign. Assessment may reveal superficial veins that are visibly engorged; palpable, hard, thready, and cordlike; and sensitive to pressure.

Varicose veins. Mild to severe leg symptoms may develop, including nocturnal cramping; a feeling of heaviness; diffuse, dull aching after prolonged standing or walking; and aching during menses. Assessment may reveal palpable nodules, orthostatic edema, and stasis pigmentation of the calves and ankles.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Primary varicose veins originate in the superficial system and are more common in women.

Venous stasis ulcer. Localized pain and bleeding arise from infected ulcerations on the lower extremities. Mottled, bluish pigmentation is characteristic, and local edema may occur.

Special Considerations

If the patient has acute leg pain, closely monitor his neurovascular status by frequently checking distal pulses and evaluating the legs for temperature, color, and sensation. Also monitor his thigh and calf circumference to evaluate bleeding into tissues from a possible fracture site. Prepare the patient for X-rays. Use sandbags to immobilize his leg; apply ice and, if needed, skeletal traction. If a fracture isn’t suspected, prepare the patient for laboratory tests to detect an infectious agent or for venography, Doppler ultrasonography, plethysmography, or angiography to determine vascular competency. Withhold food and fluids until the need for surgery has been ruled out, and withhold analgesics until a preliminary diagnosis is made. Administer an anticoagulant and antibiotic as needed.

Patient Counseling

Explain the use of anti-inflammatory drugs, ROM exercises, and assistive devices. Discuss the need for physical therapy, as appropriate, and lifestyle changes the patient should make.

Pediatric Pointers

Common pediatric causes of leg pain include a fracture, osteomyelitis, and bone cancer. If parents fail to give an adequate explanation for a leg fracture, consider the possibility of child abuse.

REFERENCES

Konstantinou, K., Hider, S. L., Jordan, J. L., Lewis, M., Dunn, K. M., & Hay, E. M. (2013). The impact of low back-related leg pain on outcomes as compared with low back pain alone: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(7), 644–654.

Schafer, A ., Hall, T., & Briffa, K. (2009). Classification of low back-related leg pain—A proposed patho-mechanism-based approach. Manual Therapy, 14(2), 222–230.

Level of Consciousness, Decreased

A decrease in the level of consciousness (LOC), from lethargy to stupor to coma, usually results from a neurologic disorder and may signal a life-threatening complication, such as hemorrhage, trauma, or cerebral edema. However, this sign can also result from a metabolic, GI, musculoskeletal, urologic, or cardiopulmonary disorder; severe nutritional deficiency; the effects of toxins; or drug use. LOC can deteriorate suddenly or gradually and can remain altered temporarily or permanently.

Consciousness is affected by the reticular activating system (RAS), an intricate network of neurons with axons extending from the brain stem, thalamus, and hypothalamus to the cerebral cortex. A disturbance in any part of this integrated system prevents the intercommunication that makes consciousness possible. Loss of consciousness can result from a bilateral cerebral disturbance, an RAS disturbance, or both. Cerebral dysfunction characteristically produces the least dramatic decrease in a patient’s LOC. In contrast, dysfunction of the RAS produces the most dramatic decrease in LOC — coma.

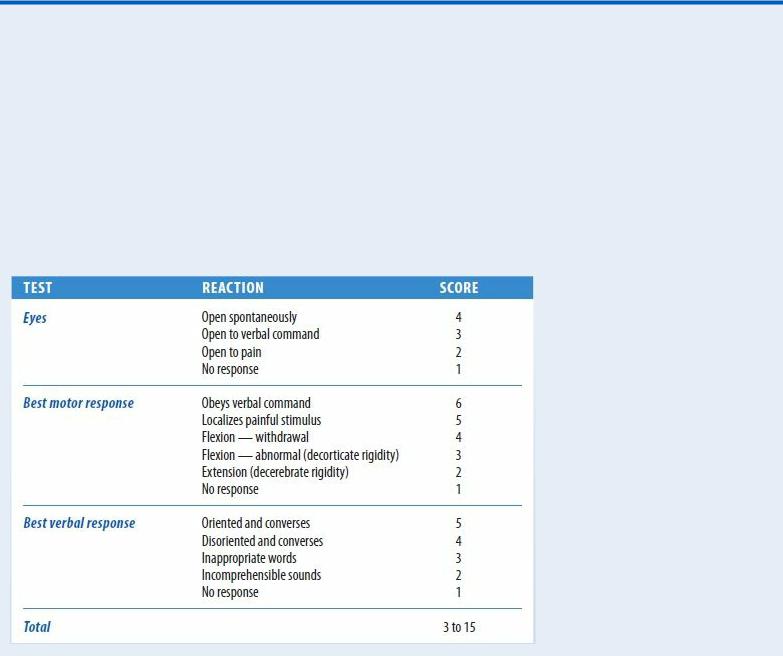

The most sensitive indicator of a decreased LOC is a change in the patient’s mental status. The Glasgow Coma Scale, which measures a patient’s ability to respond to verbal, sensory, and motor stimulation, can be used to quickly evaluate a patient’s LOC.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

After evaluating the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, use the Glasgow Coma Scale to quickly determine his LOC and to obtain baseline data. (See Glasgow Coma Scale.) If the patient’s score is 13 or less, emergency surgery may be necessary. Insert an artificial airway, elevate the head of the bed 30 degrees and, if spinal cord injury has been ruled out, turn the patient's head to the side. Prepare to suction the patient if necessary. You may need to hyperventilate him to reduce carbon dioxide levels and decrease intracranial pressure (ICP). Then determine the rate, rhythm, and depth of spontaneous respirations. Support his breathing with a handheld resuscitation bag, if necessary. If the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale score is 7 or less, intubation and resuscitation may be necessary.

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs, being alert for signs of increasing ICP, such as bradycardia and a widening pulse pressure. When his airway, breathing, and circulation are stabilized, perform a neurologic examination.

Glasgow Coma Scale

You‘ve probably heard such terms as lethargic, obtunded, and stuporous used to describe a progressive decrease in a patient‘s level of consciousness (LOC). However, the Glasgow Coma Scale provides a more accurate, less subjective method of recording such changes, grading consciousness in relation to eye opening and motor and verbal responses.

To use the Glasgow Coma Scale, test the patient‘s ability to respond to verbal, motor, and sensory stimulation. The scoring system doesn‘t determine the exact LOC, but it does provide an easy way to describe the patient‘s basic status and helps to detect and interpret changes from baseline findings. A decreased reaction score in one or more categories may signal an impending neurologic crisis. A score of 7 or less indicates severe neurologic damage.

History and Physical Examination

Try to obtain history information from the patient, if he’s lucid, and from his family. Did the patient complain of a headache, dizziness, nausea, vision or hearing disturbances, weakness, fatigue, or other problems before his LOC decreased? Has his family noticed changes in the patient’s behavior, personality, memory, or temperament? Also ask about a history of neurologic disease, cancer, or recent trauma or infections; prescribed medications; drug and alcohol use; and the development of other signs and symptoms.

Because a decreased LOC can result from a disorder affecting virtually any body system, tailor the remainder of your evaluation according to the patient’s associated symptoms.

Medical Causes