Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

signs and symptoms, such as right upper quadrant discomfort and tenderness, nausea, weight loss, and a slight fever. Examination may reveal irregular, nodular, firm hepatomegaly; ascites; peripheral edema; a bruit heard over the liver; and a right upper quadrant mass.

With pancreatic cancer, progressive jaundice — possibly with pruritus — may be the only sign. Related early findings are nonspecific, such as weight loss and back or abdominal pain. Other signs and symptoms include anorexia, nausea and vomiting, a fever, steatorrhea, fatigue, weakness, diarrhea, pruritus, and skin lesions (usually on the legs).

Jaundice: Impaired Bilirubin Metabolism

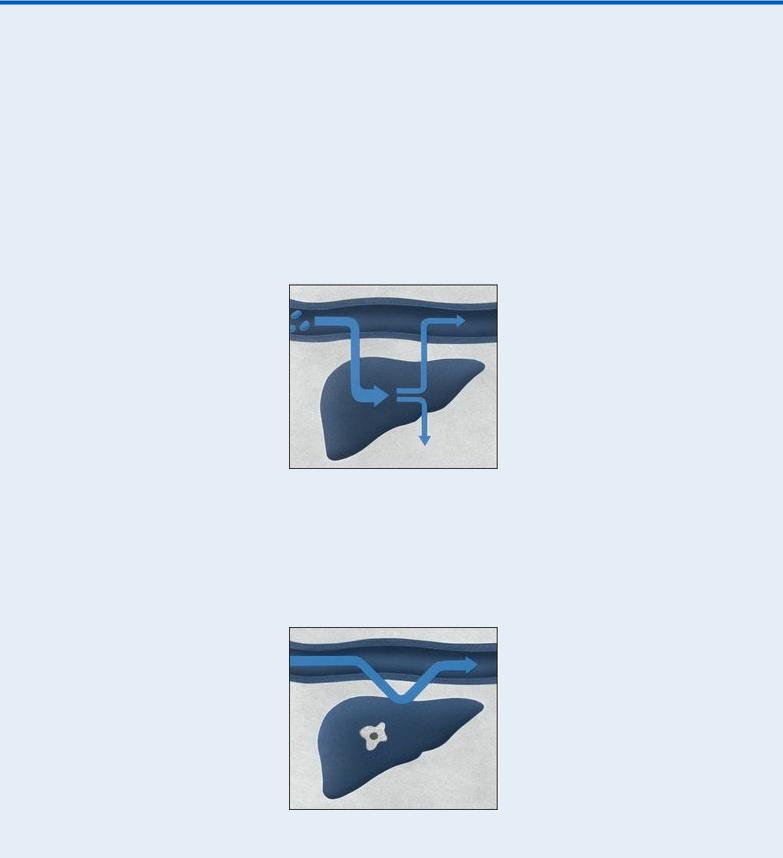

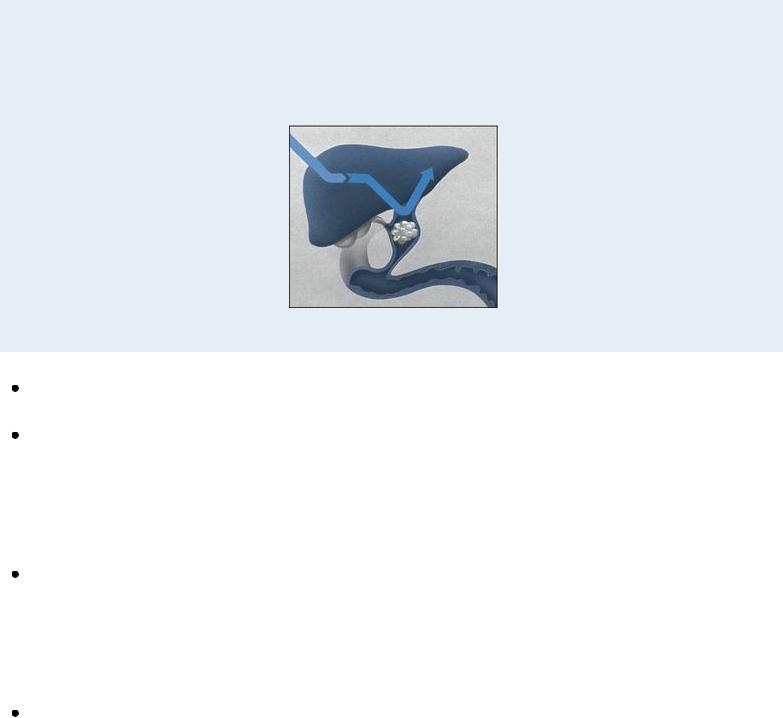

Jaundice occurs in three forms: prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic. In all three, bilirubin levels in the blood increase due to impaired metabolism.

With prehepatic jaundice, certain conditions and disorders, such as transfusion reactions and sickle cell anemia, cause massive hemolysis. Red blood cells rupture faster than the liver can conjugate bilirubin, so large amounts of unconjugated bilirubin pass into the blood, causing increased intestinal conversion of this bilirubin to water-soluble urobilinogen for excretion in urine and stools. (Unconjugated bilirubin is insoluble in water, so it can’t be directly excreted in urine.)

Hepatic jaundice results from the liver’s inability to conjugate or excrete bilirubin, leading to increased blood levels of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin. This occurs with such disorders as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and metastatic cancer and during the prolonged use of drugs metabolized by the liver.

With posthepatic jaundice, which occurs in patients with a biliary or pancreatic disorder, bilirubin forms at its normal rate, but inflammation, scar tissue, a tumor, or gallstones block the flow of bile into the intestine. This causes an accumulation of conjugated bilirubin in the blood. Water-soluble, conjugated bilirubin is excreted in urine.

Cholangitis. Obstruction and infection in the common bile duct cause Charcot’s triad: jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, and a high fever with chills.

Cholecystitis. Cholecystitis produces nonobstructive jaundice in about 25% of patients. Biliary colic typically peaks abruptly, persisting for 2 to 4 hours. The pain then localizes to the right upper quadrant and becomes constant. Local inflammation or passage of stones to the common bile duct causes jaundice. Other findings include nausea, vomiting (usually indicating the presence of a stone), a fever, profuse diaphoresis, chills, tenderness on palpation, a positive Murphy’s sign and, possibly, abdominal distention and rigidity.

Cholelithiasis. Cholelithiasis commonly causes jaundice and biliary colic. It’s characterized by severe, steady pain in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium that radiates to the right scapula or shoulder and intensifies over several hours. Accompanying signs and symptoms include nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, and restlessness. Occlusion of the common bile duct causes a fever, chills, jaundice, clay-colored stools, and abdominal tenderness. After consuming a fatty meal, the patient may experience vague epigastric fullness and dyspepsia.

Cirrhosis. With Laënnec’s cirrhosis, mild to moderate jaundice with pruritus usually signals hepatocellular necrosis or progressive hepatic insufficiency. Common early findings include ascites, weakness, leg edema, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, anorexia, weight loss, and right upper quadrant pain. Massive hematemesis and other bleeding tendencies may also occur. Other findings include an enlarged liver and parotid gland, clubbed fingers, Dupuytren’s contracture, mental changes, asterixis, fetor hepaticus, spider angiomas, and palmar erythema. Males may exhibit gynecomastia, scanty chest and axillary hair, and testicular atrophy; females may experience menstrual irregularities.

With primary biliary cirrhosis, fluctuating jaundice may appear years after the onset of other signs and symptoms, such as pruritus that worsens at bedtime (commonly the first sign), weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and vague abdominal pain. Itching may lead to skin excoriation. Associated findings include hyperpigmentation; indications of malabsorption, such as nocturnal diarrhea, steatorrhea, purpura, and osteomalacia; hematemesis from esophageal varices; ascites; edema; xanthelasmas; xanthomas on the palms, soles, and elbows; and hepatomegaly.

Dubin-Johnson syndrome. With Dubin-Johnson syndrome, which is a rare, chronic inherited syndrome, fluctuating jaundice that increases with stress is the major sign, appearing as late as age 40. Related findings include slight hepatic enlargement and tenderness, upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.

Heart failure. Jaundice due to liver dysfunction occurs in patients with severe right-sided heart failure. Other effects include jugular vein distention, cyanosis, dependent edema of the legs and sacrum, steady weight gain, confusion, hepatomegaly, nausea and vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and anorexia due to visceral edema. Ascites are a late sign. Oliguria, marked weakness, and anxiety may also occur. If left-sided heart failure develops first, other findings may include fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, tachypnea, arrhythmias, and tachycardia.

Hepatic abscess. Multiple abscesses may cause jaundice, but the primary effects are a persistent fever with chills and sweating. Other findings include steady, severe pain in the right upper quadrant or midepigastrium that may be referred to the shoulder; nausea and vomiting; anorexia; hepatomegaly; an elevated right hemidiaphragm; and ascites.

Hepatitis. Dark urine and clay-colored stools usually develop before jaundice in the late stages of acute viral hepatitis. Early systemic signs and symptoms vary and include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, a headache, anorexia, photophobia, pharyngitis, a cough, diarrhea or constipation, and a low-grade fever associated with liver and lymph node enlargement. During the icteric phase (which subsides within 2 to 3 weeks unless complications occur), systemic signs subside, but an enlarged, palpable liver may be present along with weight loss, anorexia, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness.

Pancreatitis (acute). Edema of the head of the pancreas and obstruction of the common bile duct can cause jaundice; however, the primary symptom of acute pancreatitis is usually severe epigastric pain that commonly radiates to the back. Lying with the knees flexed on the chest or sitting up and leaning forward brings relief. Early associated signs and symptoms include nausea, persistent vomiting, abdominal distention, and Turner’s or Cullen’s sign. Other findings include a fever, tachycardia, abdominal rigidity and tenderness, hypoactive bowel sounds, and crackles.

Severe pancreatitis produces extreme restlessness; mottled skin; cold, diaphoretic extremities; paresthesia; and tetany — the last two being symptoms of hypocalcemia. Fulminant pancreatitis causes massive hemorrhage.

Sickle cell anemia. Hemolysis produces jaundice in the patient with sickle cell anemia. Other findings include impaired growth and development, increased susceptibility to infection, lifethreatening thrombotic complications, and, commonly, leg ulcers, swollen (painful) joints, a fever, and chills. Bone aches and chest pain may also occur. Severe hemolysis may cause hematuria and pallor, chronic fatigue, weakness, dyspnea (or dyspnea on exertion), and tachycardia. The patient may also have splenomegaly. During a sickle cell crisis, the patient may have severe bone, abdominal, thoracic, and muscular pain; a low-grade fever; and increased weakness, jaundice, and dyspnea.

Other Causes

Drugs. Many drugs may cause hepatic injury and resultant jaundice. Examples include

acetaminophen, phenylbutazone, I.V. tetracycline, isoniazid, hormonal contraceptives, sulfonamides, mercaptopurine, erythromycin estolate, niacin, troleandomycin, androgenic steroids, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl reductase inhibitors, phenothiazines, ethanol, methyldopa, rifampin, and Dilantin.

Treatments. Upper abdominal surgery may cause postoperative jaundice, which occurs secondary to hepatocellular damage from the manipulation of organs, leading to edema and obstructed bile flow; from the administration of halothane; or from prolonged surgery resulting in shock, blood loss, or blood transfusion.

A surgical shunt used to reduce portal hypertension (such as a portacaval shunt) may also produce jaundice.

Special Considerations

To help decrease pruritus, frequently bathe the patient; apply an antipruritic lotion, such as calamine; and administer diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests to evaluate biliary and hepatic function. Laboratory studies include urine and fecal urobilinogen, serum bilirubin, liver enzyme, and cholesterol levels; prothrombin time; and a complete blood count. Other tests include ultrasonography, cholangiography, liver biopsy, and exploratory laparotomy.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient appropriate dietary changes he can make, and discuss ways to reduce pruritus.

Pediatric Pointers

Physiologic jaundice is common in neonates, developing 3 to 5 days after birth. In infants, obstructive jaundice usually results from congenital biliary atresia. A choledochal cyst — a congenital cystic dilation of the common bile duct — may also cause jaundice in children, particularly those of Japanese descent.

The list of other causes of jaundice is extensive and includes, but isn’t limited to, Crigler-Najjar syndrome, Gilbert’s disease, Rotor’s syndrome, thalassemia major, hereditary spherocytosis, erythroblastosis fetalis, Hodgkin’s disease, infectious mononucleosis, Wilson’s disease, amyloidosis, and Reye’s syndrome.

Geriatric Pointers

In patients older than age 60, jaundice is usually caused by cholestasis resulting from extrahepatic obstruction.

REFERENCES

Liebel, F., Kaur, S., Ruvolo, E., Kollias, N., & Southall, M. D. (2012). Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 132, 1901–1907.

Stokowski, L. A. (2011). Fundamentals of phototherapy for neonatal jaundice. Advances in Neonatal Care, 11, 10–21.

Jaw Pain

Jaw pain may arise from either of the two bones that hold the teeth in the jaw — the maxilla (upper

jaw) and the mandible (lower jaw). Jaw pain also includes pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), where the mandible meets the temporal bone.

Jaw pain may develop gradually or abruptly and may range from barely noticeable to excruciating, depending on its cause. It usually results from disorders of the teeth, soft tissue, or glands of the mouth or throat or from local trauma or infection. Systemic causes include musculoskeletal, neurologic, cardiovascular, endocrine, immunologic, metabolic, and infectious disorders. Life-threatening disorders, such as a myocardial infarction (MI) and tetany, also produce jaw pain as well as certain drugs (especially phenothiazines) and dental or surgical procedures.

Jaw pain is seldom a primary indicator of any one disorder; however, some causes are medical emergencies.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Ask the patient when the jaw pain began. Did it arise suddenly or gradually? Is it more severe or frequent now than when it first occurred? Sudden severe jaw pain, especially when associated with chest pain, shortness of breath, or arm pain, requires prompt evaluation because it may herald a life-threatening myocardial infarction. Perform an electrocardiogram and obtain blood samples for cardiac enzyme levels. Administer oxygen, morphine sulfate, and a vasodilator as indicated.

History and Physical Examination

Begin the patient history by asking him to describe the pain’s character, intensity, and frequency. When did he first notice the jaw pain? Where on the jaw does he feel pain? Does the pain radiate to other areas? Sharp or burning pain arises from the skin or subcutaneous tissues. Causalgia, an intense burning sensation, usually results from damage to the fifth cranial, or trigeminal, nerve. This type of superficial pain is easily localized, unlike dull, aching, boring, or throbbing pain, which originates in muscle, bone, or joints. Also ask about aggravating or alleviating factors.

Ask about recent trauma, surgery, or procedures, especially dental work. Ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as joint or chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, fatigue, a headache, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, intermittent claudication, diplopia, and hearing loss. (Keep in mind that jaw pain may accompany more characteristic signs and symptoms of life-threatening disorders such as chest pain in a patient with an MI.)

Focus your physical examination on the jaw. Inspect the painful area for redness, and palpate for edema or warmth. Facing the patient directly, look for facial asymmetry indicating swelling. Check the TMJs by placing your fingertips just anterior to the external auditory meatus and asking the patient to open and close and to thrust out and retract his jaw. Note the presence of crepitus, an abnormal scraping or grinding sensation in the joint. (Clicks heard when the jaw is widely spread apart are normal.) How wide can the patient open his mouth? Less than 1⅛″ (3 cm) or more than 2⅜″ (6 cm) between the upper and lower teeth is abnormal. Next, palpate the parotid area for pain and swelling, and inspect and palpate the oral cavity for lesions, elevation of the tongue, or masses.

Medical Causes

Angina pectoris. Angina may produce jaw pain (usually radiating from the substernal area) and

left arm pain. Angina is less severe than the pain of an MI. It’s commonly triggered by exertion, emotional stress, or ingestion of a heavy meal and usually subsides with rest and the administration of nitroglycerin. Other signs and symptoms include shortness of breath, nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, dizziness, diaphoresis, belching, and palpitations.

Arthritis. With osteoarthritis, which usually affects the small joints of the hand, aching jaw pain increases with activity (talking, eating) and subsides with rest. Other features are crepitus heard and felt over the TMJ, enlarged joints with a restricted range of motion (ROM), and stiffness on awakening that improves with a few minutes of activity. Redness and warmth are usually absent. Rheumatoid arthritis causes symmetrical pain in all joints (commonly affecting proximal finger joints first), including the jaw. The joints display limited ROM and are tender, warm, swollen, and stiff after inactivity, especially in the morning. Myalgia is common. Systemic signs and symptoms include fatigue, weight loss, malaise, anorexia, lymphadenopathy, and a mild fever. Painless, movable rheumatoid nodules may appear on the elbows, knees, and knuckles. Progressive disease causes deformities, crepitation with joint rotation, muscle weakness and atrophy around the involved joint, and multiple systemic complications.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Rheumatoid arthritis usually appears in early middle age, between ages 36 and 50, and most commonly in women.

Head and neck cancer. Many types of head and neck cancer, especially of the oral cavity and nasopharynx, produce aching jaw pain of insidious onset. Other findings include a history of leukoplakia; ulcers of the mucous membranes; palpable masses in the jaw, mouth, and neck; dysphagia; bloody discharge; drooling; lymphadenopathy; and trismus.

Hypocalcemic tetany. Besides painful muscle contractions of the jaw and mouth, hypocalcemic tetany — a life-threatening disorder — produces paresthesia and carpopedal spasms. The patient may complain of weakness, fatigue, and palpitations. Examination reveals hyperreflexia and positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs. Muscle twitching, choreiform movements, and muscle cramps may also occur. With severe hypocalcemia, laryngeal spasm may occur with stridor, cyanosis, seizures, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Ludwig’s angina. Ludwig’s angina is an acute streptococcal infection of the sublingual and submandibular spaces that produces severe jaw pain in the mandibular area with tongue elevation, sublingual edema, and drooling. A fever is a common sign. Progressive disease produces dysphagia, dysphonia, and stridor and dyspnea due to laryngeal edema and obstruction by an elevated tongue.

MI. Initially, MI causes intense, crushing substernal pain that’s unrelieved by rest or nitroglycerin. The pain may radiate to the lower jaw, left arm, neck, back, or shoulder blades. (Rarely, jaw pain occurs without chest pain.) Other findings include pallor, clammy skin, dyspnea, excessive diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting, anxiety, restlessness, a feeling of impending doom, a low-grade fever, decreased or increased blood pressure, arrhythmias, an atrial gallop, new murmurs (in many cases from mitral insufficiency), and crackles.

Sinusitis. Maxillary sinusitis produces intense boring pain in the maxilla and cheek that may radiate to the eye. This type of sinusitis also causes a feeling of fullness, increased pain on

percussion of the first and second molars, and, in those with nasal obstruction, the loss of the sense of smell. Sphenoid sinusitis causes scanty nasal discharge and chronic pain at the mandibular ramus and vertex of the head and in the temporal area. Other signs and symptoms of both types of sinusitis include a fever, halitosis, a headache, malaise, a cough, and a sore throat. Suppurative parotitis. Bacterial infection of the parotid gland by Staphylococcus aureus tends to develop in debilitated patients with dry mouth or poor oral hygiene. Besides the abrupt onset of jaw pain, a high fever, and chills, findings include erythema and edema of the overlying skin; a tender, swollen gland; and pus at the second top molar (Stensen’s ducts). Infection may lead to disorientation; shock and death are common.

Temporal arteritis. Most common in women older than age 60, temporal arteritis produces sharp jaw pain after chewing or talking. Nonspecific signs and symptoms include a low-grade fever, generalized muscle pain, malaise, fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss. Vascular lesions produce jaw pain; a throbbing, unilateral headache in the frontotemporal region; swollen, nodular, tender and, possibly, pulseless temporal arteries; and, at times, erythema of the overlying skin.

TMJ syndrome. TMJ syndrome is a common syndrome that produces jaw pain at the TMJ; spasm and pain of the masticating muscle; clicking, popping, or crepitus of the TMJ; and restricted jaw movement. Unilateral, localized pain may radiate to other head and neck areas. The patient typically reports teeth clenching, bruxism, and emotional stress. He may also experience ear pain, a headache, deviation of the jaw to the affected side upon opening the mouth, and jaw subluxation or dislocation, especially after yawning.

Tetanus. A rare life-threatening disorder caused by a bacterial toxin, tetanus produces stiffness and pain in the jaw and difficulty opening the mouth. Early nonspecific signs and symptoms (commonly unnoticed or mistaken for influenza) include a headache, irritability, restlessness, a low-grade fever, and chills. Examination reveals tachycardia, profuse diaphoresis, and hyperreflexia. Progressive disease leads to painful, involuntary muscle spasms that spread to the abdomen, back, or face. The slightest stimulus may produce reflex spasms of any muscle group. Ultimately, laryngospasm, respiratory distress, and seizures may occur.

Trigeminal neuralgia. Trigeminal neuralgia is marked by paroxysmal attacks of intense unilateral jaw pain (stopping at the facial midline) or rapid-fire shooting sensations in one division of the trigeminal nerve (usually the mandibular or maxillary division). This superficial pain, felt mainly over the lips and chin and in the teeth, lasts from 1 to 15 minutes. Mouth and nose areas may be hypersensitive. Involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve causes a diminished or absent corneal reflex on the same side. Attacks can be triggered by mild stimulation of the nerve (for example, lightly touching the cheeks), exposure to heat or cold, or consumption of hot or cold foods or beverages.

Other Causes

Drugs. Some drugs, such as phenothiazines, affect the extrapyramidal tract, causing dyskinesias; others cause tetany of the jaw secondary to hypocalcemia.

Special Considerations

If the patient is in severe pain, withhold food, liquids, and oral medications until the diagnosis is

confirmed. Administer an analgesic. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests such as jaw X-rays. Apply an ice pack if the jaw is swollen, and discourage the patient from talking or moving his jaw.

Patient Counseling

Explain the disorder and treatments the patient needs and the identification and avoidance of triggers. Teach him the proper way to insert mouth splints. Discuss ways to reduce stress.

Pediatric Pointers

Be alert for nonverbal signs of jaw pain, such as rubbing the affected area or wincing while talking or swallowing. In infants, initial signs of tetany from hypocalcemia include episodes of apnea and generalized jitteriness progressing to facial grimaces and generalized rigidity. Finally, seizures may occur.

Jaw pain in children sometimes stems from disorders uncommon in adults. Mumps, for example, causes unilateral or bilateral swelling from the lower mandible to the zygomatic arch. Parotiditis due to cystic fibrosis also causes jaw pain. When trauma causes jaw pain in children, always consider the possibility of abuse.

REFERENCES

Chang, E. I., Leon, P. , Hoffman, W. Y. , & Schmidt, B. L. (2012) . Quality of life for patients requiring surgical resection and reconstruction for mandibular osteoradionecrosis: 10-year experience at the University of California San Francisco. Head & Neck, 34(2), 207–212.

Hewson, I. D. (2011). Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: A six-year history of a case . New Zealand Dental Journal, 107, 97–100.

Jugular Vein Distention

Jugular vein distention is the abnormal fullness and height of the pulse waves in the internal or external jugular veins. For a patient in a supine position with his head elevated 45 degrees, a pulse wave height greater than 1¼″ to 1½″ (3 to 4 cm) above the angle of Louis indicates distention. Engorged, distended veins reflect increased venous pressure in the right side of the heart, which, in turn, indicates an increased central venous pressure. This common sign characteristically occurs in heart failure and other cardiovascular disorders, such as constrictive pericarditis, tricuspid stenosis, and obstruction of the superior vena cava.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Evaluating jugular vein distention involves visualizing and assessing venous pulsations. (See Evaluating Jugular Vein Distention. ) If you detect jugular vein distention in a patient with pale, clammy skin who suddenly appears anxious and dyspneic, take his blood pressure. If you note hypotension and a paradoxical pulse, suspect cardiac tamponade. Elevate the foot of the bed 20 to 30 degrees, give supplemental oxygen, and monitor cardiac status and rhythm, oxygen saturation, and mental status. Start an I.V. line for medication administration, and keep cardiopulmonary resuscitation equipment close by. Assemble the needed equipment for emergency pericardiocentesis (to relieve pressure on the heart). Throughout the procedure,

monitor the patient’s blood pressure, heart rhythm, and respirations.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, obtain a history. Has he recently gained weight? Does he have difficulty putting on shoes? Are his ankles swollen? Ask about chest pain, shortness of breath, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, anorexia, nausea or vomiting, and a history of cancer or cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, or renal disease. Obtain a drug history, noting diuretic use and dosage. Is the patient taking drugs as prescribed? Ask the patient about his regular diet patterns, noting a highsodium intake.

Next, perform a physical examination, beginning with the patient’s vital signs. Tachycardia, tachypnea, and increased blood pressure indicate fluid overload that’s stressing the heart. Inspect and palpate the patient’s extremities and face for edema. Then weigh the patient and compare that weight to his baseline.

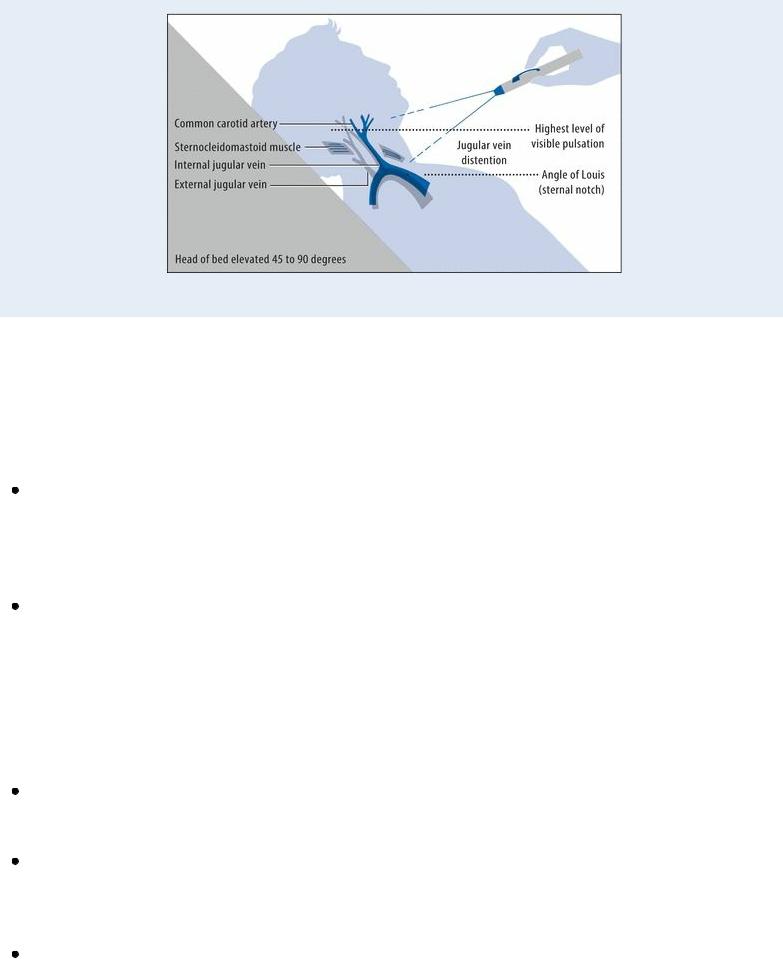

EXAMINATION TIP Evaluating Jugular Vein Distention

EXAMINATION TIP Evaluating Jugular Vein Distention

With the patient in a supine position, position him so that you can visualize jugular vein pulsations reflected from the right atrium. Elevate the head of the bed 45 to 90 degrees. (In the normal patient, veins distend only when the patient lies flat.)

Next, locate the angle of Louis (sternal notch) — the reference point for measuring venous pressure. To do so, palpate the clavicles where they join the sternum (the suprasternal notch). Place your first two fingers on the suprasternal notch. Then, without lifting them from the skin, slide them down the sternum until you feel a bony protuberance — this is the angle of Louis.

Find the internal jugular vein (which indicates venous pressure more reliably than the external jugular vein). Shine a flashlight across the patient’s neck to create shadows that highlight his venous pulse. Be sure to distinguish jugular vein pulsations from carotid artery pulsations. One way to do this is to palpate the vessel: Arterial pulsations continue, whereas venous pulsations disappear with light finger pressure. Also, venous pulsations increase or decrease with changes in body position; arterial pulsations remain constant.

Next, locate the highest point along the vein where you can see pulsations. Using a centimeter ruler, measure the distance between that high point and the sternal notch. Record this finding as well as the angle at which the patient was lying. A finding greater than 1¼″ to 1½″ (3 to 4 cm) above the sternal notch, with the head of the bed at a 45-degree angle, indicates jugular vein distention.

Auscultate his lungs for crackles and his heart for gallops, a pericardial friction rub, and muffled heart sounds. Inspect his abdomen for distention, and palpate and percuss for an enlarged liver. Finally monitor urine output and note a decrease.

Medical Causes

Cardiac tamponade. Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition that produces jugular vein distention along with anxiety, restlessness, cyanosis, chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension, and clammy skin. It also causes tachycardia, tachypnea, muffled heart sounds, a pericardial friction rub, weak or absent peripheral pulses or pulses that decrease during inspiration (pulsus paradoxus), and hepatomegaly. The patient may sit upright or lean forward to ease breathing.

Heart failure. Sudden or gradual development of right-sided heart failure commonly causes jugular vein distention, along with weakness and anxiety, cyanosis, dependent edema of the legs and sacrum, steady weight gain, confusion, and hepatomegaly. Other findings include nausea and vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and anorexia due to visceral edema. Ascites are a late sign. Massive right-sided heart failure may produce anasarca and oliguria.

If left-sided heart failure precedes right-sided heart failure, jugular vein distention is a late sign. Other signs and symptoms include fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, and arrhythmias. Auscultation reveals crackles and a ventricular gallop. Hypervolemia. Markedly increased intravascular fluid volume causes jugular vein distention, along with rapid weight gain, elevated blood pressure, bounding pulse, peripheral edema, dyspnea, and crackles.

Pericarditis (chronic constrictive). Progressive signs and symptoms of restricted heart filling include jugular vein distention that’s more prominent on inspiration (Kussmaul’s sign). The patient usually complains of chest pain. Other signs and symptoms include fluid retention with dependent edema, hepatomegaly, ascites, and a pericardial friction rub.

Superior vena cava obstruction. A tumor or, rarely, thrombosis may gradually lead to jugular vein distention when the veins of the head, neck, and arms fail to empty effectively, causing facial, neck, and upper arm edema. Metastasis of a malignant tumor to the mediastinum may cause dyspnea, a cough, substernal chest pain, and hoarseness.