Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

I

Impotence

Impotence is the inability to achieve and maintain penile erection sufficient to complete satisfactory sexual intercourse; ejaculation may or may not be affected. Impotence varies from occasional and minimal to permanent and complete. Occasional impotence occurs in about one-half of adult American men, whereas chronic impotence affects about 10 million American men.

Impotence can be classified as primary or secondary. A man with primary impotence has never been potent with a sexual partner but may achieve normal erections in other situations. This uncommon condition is difficult to treat. Secondary impotence carries a more favorable prognosis because, despite his present erectile dysfunction, the patient has completed satisfactory intercourse in the past.

Penile erection involves increased arterial blood flow secondary to psychological, tactile, and other sensory stimulation. Trapping of blood within the penis produces increased length, circumference, and rigidity. Impotence results when any component of this process — psychological, vascular, neurologic, or hormonal — malfunctions.

Organic causes of impotence include vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypogonadism, a spinal cord lesion, alcohol and drug abuse, and surgical complications. (The incidence of organic impotence associated with other medical problems increases after age 50.) Psychogenic causes range from performance anxiety and marital discord to moral or religious conflicts. Fatigue, poor health, age, and drugs can also disrupt normal sexual function.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient complains of impotence or of a condition that may be causing it, let him describe his problem without interruption. Then begin your examination in a systematic way, moving from less sensitive to more sensitive matters. Begin with a psychosocial history. Is the patient married, single, or widowed? How long has he been married or had a sexual relationship? What’s the age and health status of his sexual partner? Is he feeling stress or pressure from his partner to conceive a child? Find out about past marriages, if any, and ask him why he thinks they ended. If you can do so discreetly, ask about sexual activity outside marriage or his primary sexual relationship. Also ask about his job history, his typical daily activities, and his living situation. How well does he get along with others in his household?

Focus your medical history on the causes of erectile dysfunction. Does the patient have type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or heart disease? If so, ask about its onset and treatment. Also ask about neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis. Obtain a surgical history, emphasizing neurologic, vascular, and urologic surgery. If trauma may be causing the patient’s impotence, find out the date of the injury as well as its severity, associated effects, and treatment. Ask about alcohol intake, drug use or abuse, smoking, diet, and exercise. Obtain a urologic history, including voiding problems and past injury.

Next, ask the patient when his impotence began. How did it progress? What’s its current status?

Make your questions specific, but remember that he may have difficulty discussing sexual problems or may not understand the physiology involved.

The following sample questions may yield helpful data: When was the first time you remember not being able to initiate or maintain an erection? How often do you wake in the morning or at night with an erection? Do you have wet dreams? Has your sexual drive changed? How often do you try to have intercourse with your partner? How often would you like to? Can you ejaculate with or without an erection? Do you experience orgasm with ejaculation?

Ask the patient to rate the quality of a typical erection on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being completely flaccid and 10 being completely erect. Using the same scale, also ask him to rate his ability to ejaculate during sexual activity, with 0 being never and 10 being always.

Next, perform a brief physical examination. Inspect and palpate the genitalia and prostate for structural abnormalities. Assess the patient’s sensory function, concentrating on the perineal area. Next, test motor strength and deep tendon reflexes in all extremities, and note other neurologic deficits. Take the patient’s vital signs and palpate his pulses for quality. Note any signs of peripheral vascular disease, such as cyanosis and cool extremities. Auscultate for abdominal aortic, femoral, carotid, or iliac bruits and palpate for thyroid gland enlargement.

Medical Causes

Central nervous system disorders. Spinal cord lesions from trauma produce sudden impotence. A complete lesion above S2 (upper motor neuron lesion) disrupts descending motor tracts to the genital area, causing a loss of voluntary erectile control but not of reflex erection and reflex ejaculation. However, a complete lesion in the lumbosacral spinal cord (lower motor neuron lesion) causes a loss of reflex ejaculation and reflex erection. Spinal cord tumors and degenerative diseases of the brain and spinal cord (such as multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) cause progressive impotence.

Endocrine disorders. Hypogonadism from testicular or pituitary dysfunction may lead to impotence from a deficient secretion of androgens (primarily testosterone). Adrenocortical and thyroid dysfunction and chronic hepatic disease may also cause impotence because these organs play a role (although minor) in sex hormone regulation.

Penile disorders. With Peyronie’s disease, the penis is bent, making erection painful and penetration difficult and eventually impossible. Phimosis prevents erection until circumcision releases the constricted foreskin. Other inflammatory, infectious, or destructive diseases of the penis may also cause impotence.

Psychological distress. Impotence can result from diverse psychological causes, including depression, performance anxiety, memories of previous traumatic sexual experiences, moral or religious conflicts, and troubled emotional or sexual relationships.

Other Causes

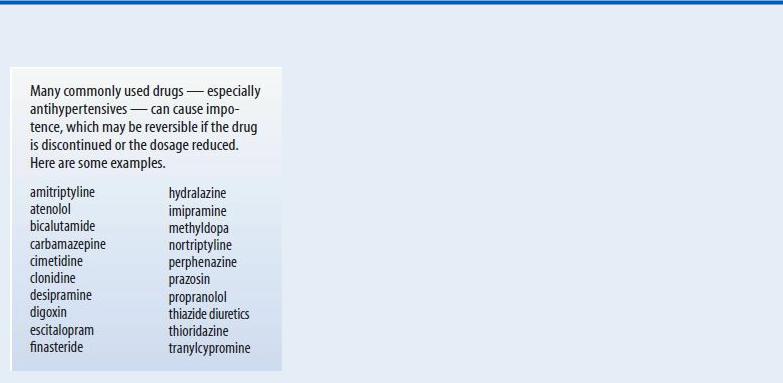

Alcohol and drugs. Alcoholism and drug abuse are associated with impotence, as are many prescription drugs, especially antihypertensives. (See Drugs That May Cause Impotence.) Surgery. Surgical injury to the penis, bladder neck, urinary sphincter, rectum, or perineum can cause impotence, as can injury to local nerves or blood vessels.

Special Considerations

Care begins by ensuring privacy, confirming confidentiality, and establishing a rapport with the patient. No other medical condition affecting males is as potentially frustrating, humiliating, and devastating to self-esteem and significant relationships as impotence. Help the patient feel comfortable about discussing his sexuality. This begins with feeling comfortable about your own sexuality and adopting an accepting attitude about the sexual experiences and preferences of others.

Drugs That May Cause Impotence

Prepare the patient for screening tests for hormonal irregularities and for Doppler studies of penile blood pressure to rule out vascular insufficiency. Other tests include voiding studies, nerve conduction tests, evaluation of nocturnal penile tumescence, and psychological screening.

Treatment of psychogenic impotence may involve counseling for the patient and his sexual partner; treatment of organic impotence focuses on reversing the cause, if possible. Other forms of treatment include surgical revascularization, drug-induced erection, surgical repair of a venous leak, and penile prostheses.

Patient Counseling

Discuss with the patient the importance of keeping follow-up appointments and maintaining therapy for underlying medical disorders. Encourage him to talk openly about his needs, desires, fears, and anxieties, and correct any misconceptions he may have. Urge him to discuss his feelings with his partner as well as what role both of them want sexual activity to play in their lives.

Geriatric Pointers

Most people erroneously believe that sexual performance normally declines with age and that elderly people are incapable of or aren’t interested in sex or that they can’t find elderly partners who are interested in sex. Organic disease must be ruled out in elderly people who suffer from sexual dysfunction before counseling to improve sexual performance can start.

REFERENCES

Hatzimouratidis, K., Amar, E., Eardley, I., Giuliano, F., Hatzichristou, D., Montorsi, F., … Wespes, E. (2010). Guidelines on male sexual dysfunction: Erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. European Urology, 57, 804–814.

Ruige, J. B., Mahmoud, A. M., De Bacquer, D., & Kaufman, J. M. (2011) . Endogenous testosterone and cardiovascular disease in healthy men: A meta-analysis. Heart, 97, 870–875.

Insomnia

Insomnia is the inability to fall asleep, remain asleep, or feel refreshed by sleep. Acute and transient during periods of stress, insomnia may become chronic, causing constant fatigue, extreme anxiety as bedtime approaches, and psychiatric disorders. This common complaint is experienced occasionally by about 25% of Americans and chronically by another 10%.

Physiologic causes of insomnia include jet lag, arguing, and lack of exercise. Pathophysiologic causes range from medical and psychiatric disorders to pain, adverse effects of a drug, and idiopathic factors. Complaints of insomnia are subjective and require close investigation; for example, the patient may mistakenly attribute his fatigue from an organic cause, such as anemia, to insomnia.

History and Physical Examination

Take a thorough sleep and health history. Find out when the patient’s insomnia began and the circumstances surrounding it. Is the patient trying to stop using a sedative? Does he take a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant, such as an amphetamine, pseudoephedrine, a theophylline derivative, phenylpropanolamine, cocaine, or a drug that contains caffeine, or does he drink caffeinated beverages?

Find out if the patient has a chronic or acute condition, the effects of which may be disturbing his sleep, particularly cardiac or respiratory disease or painful or pruritic conditions. Ask if he has an endocrine or neurologic disorder, or a history of drug or alcohol abuse. Is he a frequent traveler who suffers from jet lag? Does he use his legs a lot during the day and then feel restless at night? Ask about daytime fatigue and regular exercise. Also ask if he commonly finds himself gasping for air, experiencing apnea, or frequently repositioning his body. If possible, consult the patient’s spouse or sleep partner because the patient may be unaware of his own behavior. Ask how many pillows the patient uses to sleep.

Assess the patient’s emotional status, and try to estimate his level of self-esteem. Ask about personal and professional problems and psychological stress. Also ask if he experiences hallucinations and note behavior that may indicate alcohol withdrawal. After reviewing complaints that suggest an undiagnosed disorder, perform a physical examination.

Medical Causes

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Abrupt cessation of alcohol intake after long-term use causes insomnia that may persist for up to 2 years. Other early effects of this acute syndrome include excessive diaphoresis, tachycardia, hypertension, tremors, restlessness, irritability, a headache, nausea, flushing, and nightmares. Progression to delirium tremens produces confusion, disorientation, paranoia, delusions, hallucinations, and seizures.

Generalized anxiety disorder. Anxiety can cause chronic insomnia as well as symptoms of

tension, such as fatigue and restlessness; signs of autonomic hyperactivity, such as diaphoresis, dyspepsia, and high resting pulse and respiratory rates; and signs of apprehension.

Mood (affective) disorders. Depression commonly causes chronic insomnia with difficulty falling asleep, waking and being unable to fall back to sleep, or waking early in the morning. Related findings include dysphoria (a primary symptom), decreased appetite with weight loss or increased appetite with weight gain, and psychomotor agitation or retardation. The patient experiences loss of interest in his usual activities, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, indecisiveness, and recurrent thoughts of death.

Manic episodes produce a decreased need for sleep with an elevated mood and irritability. Related findings include increased energy and activity, fast speech, speeding thoughts, inflated self-esteem, easy distractibility, and involvement in high-risk activities such as reckless driving. Nocturnal myoclonus. With nocturnal myoclonus, a seizure disorder, involuntary and fleeting muscle jerks of the legs occur every 20 to 40 seconds, disturbing sleep.

Sleep apnea syndrome. Apneic periods begin with the onset of sleep, continue for 10 to 90 seconds, and end with a series of gasps and arousal. With central sleep apnea, respiratory movement ceases for the apneic period; with obstructive sleep apnea, upper airway obstruction blocks incoming air, although breathing movements continue. Some patients display both types of apnea. Repeated possibly hundreds of times during the night, this cycle alternates with bradycardia and tachycardia. Associated findings include a morning headache, daytime fatigue, hypertension, ankle edema, and personality changes, such as hostility, paranoia, and agitated depression.

Thyrotoxicosis. Difficulty falling asleep and then sleeping for only a brief period is one of the characteristic symptoms of thyrotoxicosis. Cardiopulmonary features include dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, and an atrial or a ventricular gallop. Other findings include weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, nervousness, diaphoresis, hypersensitivity to heat, an enlarged thyroid, and exophthalmos.

Other Causes

Drugs. Use of, abuse of, or withdrawal from sedatives or hypnotics may produce insomnia. CNS stimulants — including amphetamines, theophylline derivatives, pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, cocaine, and caffeinated beverages — may also produce insomnia.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Herbal remedies, such as ginseng and green tea, can also cause insomnia.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for tests to evaluate his insomnia, such as blood and urine studies for 17hydroxycorticosteroids and catecholamines, polysomnography (including an EEG, electrooculography, and electrocardiography), and sleep EEG.

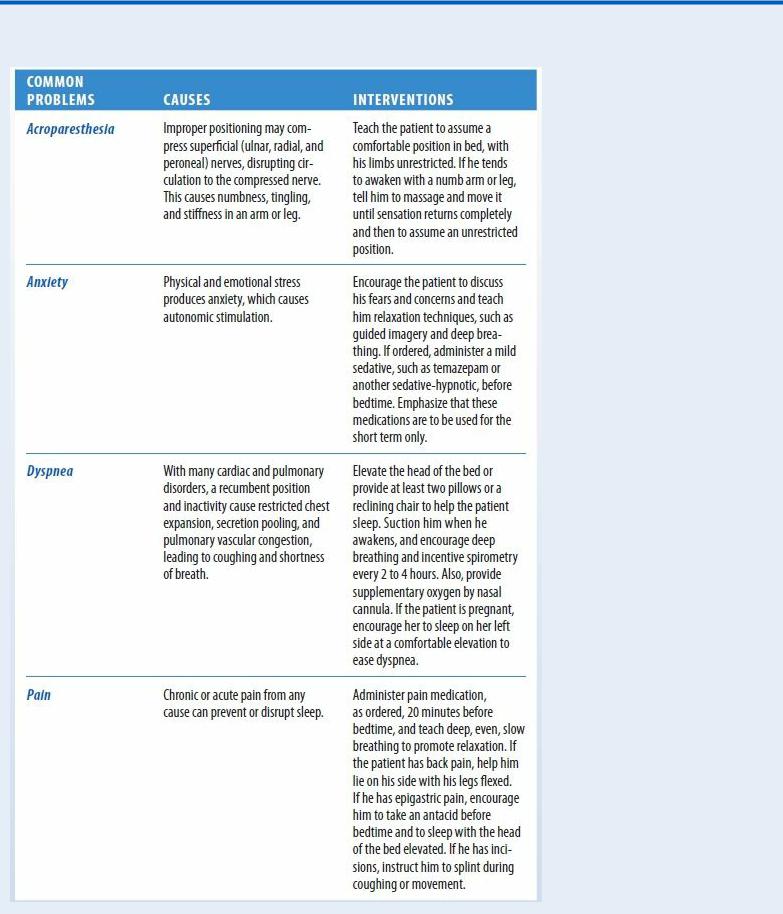

Teach the patient comfort and relaxation techniques to promote natural sleep. (See Tips for Relieving Insomnia, page 416.) Advise him to awaken and retire at the same time each day and to

exercise regularly, but not close to bedtime.

Tips for Relieving Insomnia

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient techniques to promote comfort and relaxation. Discuss the appropriate use of tranquilizers or sedatives. Refer the patient to counseling or a sleep disorder clinic, as needed.

Pediatric Pointers

Insomnia in early childhood may develop along with separation anxiety at ages 2 to 3, after a stressful or tiring day, or during illness or teething. In children ages 6 to 11, insomnia usually reflects residual excitement from the day’s activities; a few children continue to have bedtime fears. Sleep problems are common in foster children.

REFERENCES

Lapierre, S., Boyer, R., Desjardins, S., Dubé, M., Lorrain, D., Préville, M., … Brassard, J. (2012) . Daily hassles, physical illness, and sleep problems in older adults with wishes to die. Internation Psychogeriatrics, 24, 243–252.

Li, S., Lam, S., Yu, M., Zhang, J., & Wing, Y. (2010). Nocturnal sleep disturbances as a predictor of suicide attempts among psychiatric outpatients: A clinical, epidemiologic, prospective study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 1440–1446.

Intermittent Claudication

Most common in the legs, intermittent claudication is cramping limb pain brought on by exercise and relieved by 1 to 2 minutes of rest. This pain may be acute or chronic; when acute, it may signal acute arterial occlusion. Intermittent claudication is most common in men ages 50 to 60 with a history of diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or tobacco use. Without treatment, it may progress to pain at rest. With chronic arterial occlusion, limb loss is uncommon because collateral circulation usually develops.

With occlusive artery disease, intermittent claudication results from an inadequate blood supply. Pain in the calf (the most common area) or foot indicates disease of the femoral or popliteal arteries; pain in the buttocks and upper thigh, disease of the aortoiliac arteries. During exercise, the pain typically results from the release of lactic acid due to anaerobic metabolism in the ischemic segment, secondary to obstruction. When exercise stops, the lactic acid clears and the pain subsides.

Intermittent claudication may also have a neurologic cause: narrowing of the vertebral column at the level of the cauda equina. This condition creates pressure on the nerve roots to the lower extremities. Walking stimulates circulation to the cauda equina, causing increased pressure on those nerves and resultant pain.

Physical findings include pallor on elevation, rubor on dependency (especially the toes and soles), loss of hair on the toes, and diminished arterial pulses.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has sudden intermittent claudication with severe or aching leg pain at rest, check the leg's temperature and color and palpate femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis pulses. Ask about numbness and tingling. Suspect acute arterial occlusion if pulses are absent; if the leg feels cold and looks pale, cyanotic, or mottled; and if paresthesia and pain are present. Mark the area of pallor, cyanosis, or mottling, and reassess it frequently, noting an increase in the area.

Don't elevate the leg. Protect it, allowing nothing to press on it. Prepare the patient for

preoperative blood tests, urinalysis, electrocardiography, chest X-rays, lower-extremity Doppler studies, and angiography. Start an I.V. line and administer an anticoagulant and analgesics.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient has chronic intermittent claudication, gather history data first. Ask how far he can walk before pain occurs and how long he must rest before it subsides. Can he walk less far now than before or does he need to rest longer? Does the pain-rest pattern vary? Has this symptom affected his lifestyle?

Obtain a history of risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. Next, ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as paresthesia in the affected limb and visible changes in the color of the fingers (white to blue to pink) when he’s smoking, exposed to cold, or under stress. If the patient is male, does he experience impotence?

Focus the physical examination on the cardiovascular system. Palpate for femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses. Note character, amplitude, and bilateral equality. Diminished or absent popliteal and pedal pulses with the femoral pulse present may indicate atherosclerotic disease of the femoral artery. Diminished femoral and distal pulses may indicate disease of the terminal aorta or iliac branches. Absent pedal pulses with normal femoral and popliteal pulses may indicate Buerger’s disease.

Listen for bruits over the major arteries. Note color and temperature differences between his legs or compared with his arms; also note where on his leg the changes in temperature and color occur. Elevate the affected leg for 2 minutes; if it becomes pale or white, blood flow is severely decreased. When the leg hangs down, how long does it take for color to return? (Thirty seconds or longer indicates severe disease.) If possible, check the patient’s deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) after exercise; note if they’re diminished in his lower extremities.

Examine the patient’s feet, toes, and fingers for ulceration and inspect his hands and lower legs for small, tender nodules and erythema along blood vessels. Note the quality of his nails and the amount of hair on his fingers and toes.

If the patient has arm pain, inspect his arms for a change in color (to white) on elevation. Next, palpate for changes in temperature, muscle wasting, and a pulsating mass in the subclavian area. Palpate and compare the radial, ulnar, brachial, axillary, and subclavian pulses to identify obstructed areas.

Medical Causes

Arterial occlusion (acute). Acute arterial occlusion produces intense intermittent claudication. A saddle embolus may affect both legs. Associated findings include paresthesia, paresis, and a sensation of cold in the affected limb. The limb is cool, pale, and cyanotic (mottled) with absent pulses below the occlusion. Capillary refill time is increased.

Arteriosclerosis obliterans. Arteriosclerosis obliterans usually affects the femoral and popliteal arteries, causing intermittent claudication (the most common symptom) in the calf. Typical associated findings include diminished or absent popliteal and pedal pulses, coolness in the affected limb, pallor on elevation, and profound limb weakness with continuing exercise. Other possible findings include numbness, paresthesia, and, in severe disease, pain in the toes or

foot while at rest, ulceration, and gangrene.

Buerger’s disease. Buerger’s disease typically produces intermittent claudication of the instep. Men are affected more than women are; most of the affected men smoke and are between ages 20 and 40. It’s common in the Orient, Southeast Asia, India, and the Middle East and rare in Blacks. Early signs include migratory superficial nodules and erythema along extremity blood vessels (nodular phlebitis) as well as migratory venous phlebitis. With exposure to cold, the feet initially become cold, cyanotic, and numb; later, they redden, become hot, and tingle. Occasionally, Buerger’s disease also affects the hands and can cause painful ulcerations on the fingertips. Other characteristic findings include impaired peripheral pulses, paresthesia of the hands and feet, and migratory superficial thrombophlebitis.

Neurogenic claudication. Neurospinal disease causes pain from neurogenic intermittent claudication that requires a longer rest time than the 2 to 3 minutes needed in vascular claudication. Associated findings include paresthesia, weakness and clumsiness when walking, and hypoactive DTRs after walking. Pulses are unaffected.

Special Considerations

Encourage the patient to exercise to improve collateral circulation and increase venous return and advise him to avoid prolonged sitting or standing as well as crossing his legs at the knees. If intermittent claudication interferes with the patient’s lifestyle, he may require diagnostic tests (Doppler flow studies, arteriography, and digital subtraction angiography) to determine the location and degree of occlusion.

Patient Counseling

Discuss the risk factors for intermittent claudication. Stress the importance of inspecting legs and feet for ulcers. Explain ways the patient can protect his extremities from injury and the elements. Teach him which signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

Intermittent claudication rarely occurs in children. Although it sometimes develops in patients with coarctation of the aorta, extensive compensatory collateral circulation typically prevents manifestation of this sign. Muscle cramps from exercise and growing pains may be mistaken for intermittent claudication in children.

REFERENCES

Deeks, S. G. (2011). HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annual Review of Medicine, 62, 141–155.

Mangili, A., Polak, J. F., Quach, L. A., Gerrior, J., & Wanke, C. A. (2011). Markers of atherosclerosis and inflammation and mortality in patients with HIV infection. Atherosclerosis, 214, 468–473.

J

Jaundice[Icterus]

A yellow discoloration of the skin, mucous membranes, or sclera of the eyes, jaundice indicates excessive levels of conjugated or unconjugated bilirubin in the blood. In fair-skinned patients, it’s most noticeable on the face, trunk, and sclera; in dark-skinned patients, on the hard palate, sclera, and conjunctiva.

Jaundice is most apparent in natural sunlight. In fact, it may be undetectable in artificial or poor light. It’s commonly accompanied by pruritus (because bile pigment damages sensory nerves), dark urine, and clay-colored stools.

Jaundice may result from any of three pathophysiologic processes. (See Jaundice: Impaired Bilirubin Metabolism.) It may be the only warning sign of certain disorders such as pancreatic cancer.

History and Physical Examination

Documenting a history of the patient’s jaundice is critical in determining its cause. Begin by asking the patient when he first noticed the jaundice. Does he also have pruritus, clay-colored stools, or dark urine? Ask about past episodes or a family history of jaundice. Does he have nonspecific signs or symptoms, such as fatigue, a fever, or chills; GI signs or symptoms, such as anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, weight loss, or vomiting; or cardiopulmonary symptoms, such as shortness of breath or palpitations? Ask about alcohol use and a history of cancer or liver or gallbladder disease. Has the patient lost weight recently? Also, obtain a drug history. Ask about a history of hepatitis, gallstones, or liver or pancreatic disease.

Perform the physical examination in a room with natural light. Make sure that the orange-yellow hue is jaundice and not due to hypercarotenemia, which is more prominent on the palms and soles and doesn’t affect the sclera. Inspect the patient’s skin for texture and dryness and for hyperpigmentation and xanthomas. Look for spider angiomas or petechiae, clubbed fingers, and gynecomastia. If the patient has heart failure, auscultate for arrhythmias, murmurs, and gallops, as well as crackles and abnormal bowel sounds. Palpate the lymph nodes for swelling and the abdomen for tenderness, pain, and swelling. Palpate and percuss the liver and spleen for enlargement, and test for ascites with the shifting dullness and fluid wave techniques. Obtain baseline data on the patient’s mental status: Slight changes in sensorium may be an early sign of deteriorating hepatic function.

Medical Causes

Carcinoma. Cancer of the ampulla of Vater initially produces fluctuating jaundice, mild abdominal pain, a recurrent fever, and chills. Occult bleeding may be its first sign. Other findings include weight loss, pruritus, and back pain.

Hepatic cancer (primary liver cancer or another cancer that has metastasized to the liver) may cause jaundice by causing obstruction of the bile duct. Even advanced cancer causes nonspecific