Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Many of the causes described in this section also produce hematuria in children. However, cyclophosphamide is more likely to cause hematuria in children than in adults.

Common causes of hematuria that chiefly affect children include congenital anomalies, such as obstructive uropathy and renal dysplasia; birth trauma; hematologic disorders, such as vitamin K deficiency, hemophilia, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome; certain neoplasms, such as Wilms tumor, bladder cancer, and rhabdomyosarcoma; allergies; and foreign bodies in the urinary tract. Artifactual hematuria may result from recent circumcision.

Geriatric Pointers

Evaluation of hematuria in elderly patients should include a urine culture, excretory urography or sonography, and consultation with a urologist.

REFERENCES

Berthoux, F., Suzuki, H., Thibaudin, L., Yanagawa, H., Maillard, N., Mariat, C., … Novak, J. (2012). Autoantibodies targeting galactosedeficient IgA1 associate with progression of IgA nephropathy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 23, 1579–1587.

Roberts, I. S., Cook, H. T., Troyanov, S ., Alpers, C. E., Amore, A., Barratt, J., … Zhang, H. (2009). The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney International, 76, 546–556.

Hemianopsia

Hemianopsia is a loss of vision in one-half of the normal visual field (usually the right or left half) of one or both eyes. However, if the visual field defects are identical in both eyes but affect less than half the field of vision in each eye (incomplete homonymous hemianopsia), the lesion may be in the occipital lobe; otherwise, it probably involves the parietal or temporal lobe. (See Recognizing Types of Hemianopsia.)

Hemianopsia is caused by a lesion affecting the optic chiasm, tract, or radiation. Defects in visual perception due to cerebral lesions are usually associated with impaired color vision.

History and Physical Examination

Suspect a visual field defect if the patient seems startled when you approach him from one side or if he fails to see objects placed directly in front of him. To help determine the type of defect, compare the patient’s visual fields with your own — assuming that yours are normal. First, ask the patient to cover his right eye while you cover your left eye. Then move a pen or similarly shaped object from the periphery of his (and your) uncovered eye into his field of vision. Ask the patient to indicate when he first sees the object. Does he see it at the same time you do? After you do? Repeat this test in each quadrant of both eyes. Then, for each eye, plot the defect by shading the area of a circle that corresponds to the area of vision loss.

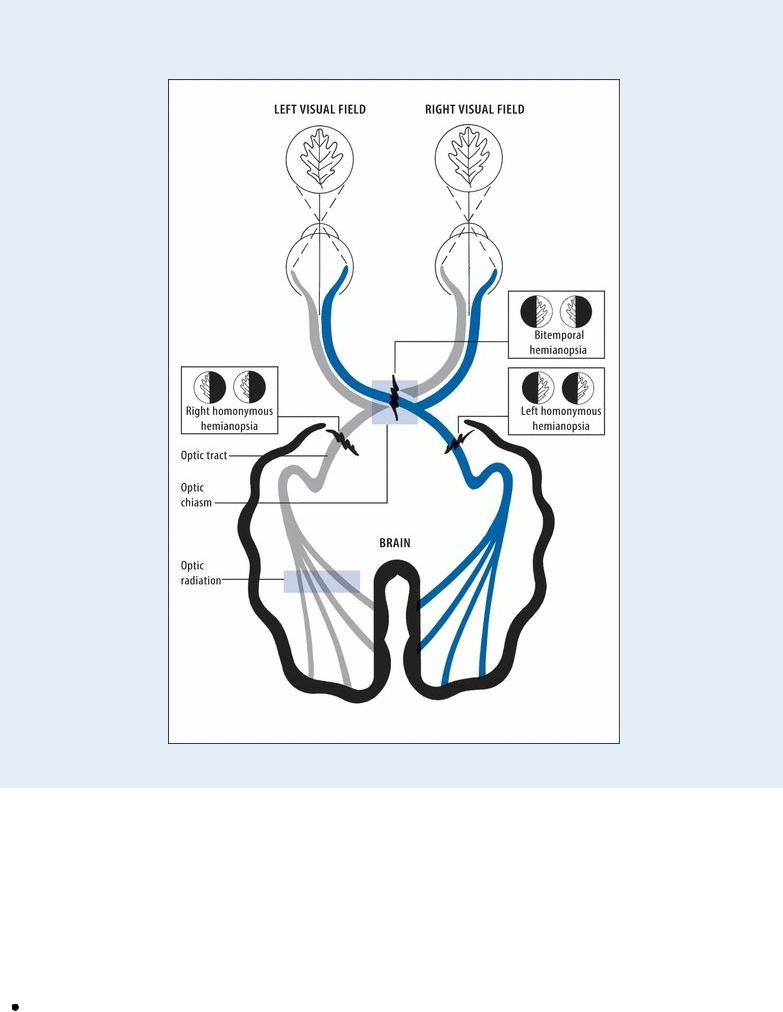

Recognizing Types of Hemianopsia

Lesions of the optic pathways cause visual field defects. The lesion's site determines the type of defect. For example, a lesion of the optic chiasm involving only those fibers that cross over to the opposite side causes bitemporal hemianopsia — vision loss in the temporal half of each

field. However, a lesion of the optic tract or a complete lesion of the optic radiation produces vision loss in the same half of each field — either left or right homonymous hemianopsia.

Next, evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC), take his vital signs, and check his pupillary reaction and motor response. Ask if he has recently experienced a headache, dysarthria, or seizures. Does he have ptosis or facial or extremity weakness? Hallucinations or loss of color vision? When did neurologic symptoms start? Obtain a medical history, noting especially eye disorders, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and recent head trauma.

Medical Causes

Carotid artery aneurysm. An aneurysm in the internal carotid artery can cause contralateral or bilateral defects in the visual fields. It can also cause hemiplegia, a decreased LOC, a headache,

aphasia, behavior disturbances, and unilateral hypoesthesia.

Occipital lobe lesion. The most common symptoms arising from a lesion of one occipital lobe are incomplete homonymous hemianopsia, scotomas, and impaired color vision. The patient may also experience visual hallucinations — flashes of light or color or visions of objects, people, animals, or geometric forms. These may appear in the defective field or may move toward it from the intact field.

Parietal lobe lesion. Parietal lobe lesion produces homonymous hemianopsia and sensory deficits, such as an inability to perceive body position or passive movement or to localize tactile, thermal, or vibratory stimuli. It may also cause apraxia and visual or tactile agnosia.

Pituitary tumor. A tumor that compresses nerve fibers supplying the nasal half of both retinas causes complete or partial bitemporal hemianopsia that first occurs in the upper visual fields but later can progress to blindness. Related findings include blurred vision, diplopia, a headache and, rarely, somnolence, hypothermia, and seizures.

Stroke. Hemianopsia can result when a hemorrhagic, thrombotic, or embolic stroke affects part of the optic pathway. Associated signs and symptoms vary according to the location and size of the stroke but may include a decreased LOC; intellectual deficits, such as memory loss and poor judgment; personality changes; emotional lability; a headache; and seizures. The patient may also develop contralateral hemiplegia, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, a unilateral sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, blurred vision, decreased visual acuity, and diplopia. He may also experience urine retention or incontinence, constipation, and vomiting.

Special Considerations

If the patient’s visual field defect is significant, further testing, such as perimetry or a tangent screen examination, may be indicated.

To avoid startling the patient, approach him from the unaffected side and position his bed so that his unaffected side faces the door. If he’s ambulatory, remove objects that could cause falls and alert him to other possible hazards. Place his clock and other personal objects within his field of vision, and avoid putting dangerous objects (such as hot dishes) where he can’t see them.

Patient Counseling

Discuss compensation techniques and stress safety measures.

Pediatric Pointers

In a child, a brain tumor is the most common cause of hemianopsia. To help detect this sign, look for nonverbal clues such as the child reaching for a toy but missing it. To help him compensate for hemianopsia, place objects within his visual field; teach his parents to do this as well.

REFERENCES

Mack, G. S. (2011). ReNeuron and stem cells get green light for neural stem cell trials. Natural Biotechnology, 29(2), 95–97.

Ohira, K., Furuta, T., Hioki, H., Nakamura, K. C., Kuramoto, E., Tanaka, Y ., … Nakamura, S. (2010). Ischemia-induced neurogenesis of neocortical layer 1 progenitor cells. Natural Neuroscience, 13(2), 173–179.

Hemoptysis

Frightening to the patient and commonly ominous, hemoptysis is the expectoration of blood or bloody sputum from the lungs or tracheobronchial tree. It’s sometimes confused with bleeding from the mouth, throat, nasopharynx, or GI tract. (See Identifying Hemoptysis.) Expectoration of 200 mL of blood in a single episode suggests severe bleeding, whereas expectoration of 400 mL in 3 hours or more than 600 mL in 16 hours signals a life-threatening crisis.

Hemoptysis usually results from chronic bronchitis, lung cancer, or bronchiectasis. However, it may also result from inflammatory, infectious, cardiovascular, or coagulation disorders and, rarely, from a ruptured aortic aneurysm. In up to 15% of patients, the cause is unknown. The most common causes of massive hemoptysis are lung cancer, bronchiectasis, active tuberculosis (TB), and cavitary pulmonary disease from necrotic infections or TB.

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Hemoptysis

EXAMINATION TIP Identifying Hemoptysis

These guidelines will help you distinguish hemoptysis from epistaxis, hematemesis, and brown, red, or pink sputum.

HEMOPTYSIS

Typically frothy because it's mixed with air, hemoptysis is typically bright red with an alkaline pH (tested with nitrazine paper). It's strongly suggested by the presence of respiratory signs and symptoms, including a cough, a tickling sensation in the throat, and blood produced from repeated coughing episodes. (You can rule out epistaxis because the patient's nasal passages and posterior pharynx are usually clear.)

HEMATEMESIS

The usual site of hematemesis is the GI tract; the patient vomits or regurgitates coffee-ground material that contains food particles, tests positive for occult blood, and has an acid pH. However, he may vomit bright red blood or swallowed blood from the oral cavity and nasopharynx. After an episode of hematemesis, the patient may have stools with traces of blood and may also complain of dyspepsia.

BROWN, RED, OR PINK SPUTUM

Brown, red, or pink sputum can result from oxidation of inhaled bronchodilators. Sputum that looks like old blood may result from rupture of an amebic abscess into the bronchus. Red or brown sputum may occur in a patient with pneumonia caused by the enterobacterium Serratia marcescens.

Several pathophysiologic processes can cause hemoptysis. (See What Happens in Hemoptysis.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient coughs up copious amounts of blood, endotracheal intubation may be required. Suction frequently to remove blood. Lavage may be necessary to loosen tenacious secretions

or clots. Massive hemoptysis can cause airway obstruction and asphyxiation. Insert an I.V. line to allow fluid replacement, drug administration, and blood transfusions, if needed. An emergency bronchoscopy should be performed to identify the bleeding site. Monitor the patient's blood pressure and pulse to detect hypotension and tachycardia, and draw an arterial blood sample for laboratory analysis to monitor respiratory status.

What Happens in Hemoptysis

Hemoptysis results from bleeding into the respiratory tract by bronchial or pulmonary vessels. Bleeding reflects alterations in the vascular walls and in blood-clotting mechanisms. It can result from any of these pathophysiologic processes:

Hemorrhage and diapedesis of red blood cells from the pulmonary microvasculature into the alveoli

Necrosis of lung tissue that causes inflammation and rupture of blood vessels or hemorrhage into the alveolar spaces

Rupture of an aortic aneurysm into the tracheobronchial tree

Rupture of distended endobronchial blood vessels from pulmonary hypertension due to mitral stenosis

Rupture of a pulmonary arteriovenous fistula or of bronchial or pulmonary artery or pulmonary venous collateral channels

Sloughing of a caseous lesion into the tracheobronchial tree Ulceration and erosion of the bronchial epithelium

History and Physical Examination

If the hemoptysis is mild, ask the patient when it began. Has he ever coughed up blood before? About how much blood is he coughing up now and about how often? Ask about a history of cardiac, pulmonary, or bleeding disorders. If he’s receiving anticoagulant therapy, find out the drug, its dosage and schedule, and the duration of therapy. Is he taking other prescription drugs? Does he smoke? Ask the patient if he has had a recent infection. Has he been exposed to TB? When was his last tine test and what were the results?

Take the patient’s vital signs and examine his nose, mouth, and pharynx for sources of bleeding. Inspect the configuration of his chest and look for abnormal movement during breathing, the use of accessory muscles, and retractions. Observe his respiratory rate, depth, and rhythm. Finally, examine his skin for lesions.

Next, palpate the patient’s chest for diaphragm level and for tenderness, respiratory excursion, fremitus, and abnormal pulsations; then percuss for flatness, dullness, resonance, hyperresonance, and tympany. Finally, auscultate the lungs, noting especially the quality and intensity of breath sounds. Also auscultate for heart murmurs, bruits, and pleural friction rubs.

Obtain a sputum sample and examine it for overall quantity, for the amount of blood it contains, and for its color, odor, and consistency.

Medical Causes

Bronchial adenoma. Bronchial adenoma is an insidious disorder that causes recurring hemoptysis in up to 30% of patients, along with a chronic cough and local wheezing. Bronchiectasis. Inflamed bronchial surfaces and eroded bronchial blood vessels cause hemoptysis, which can vary from blood-tinged sputum to blood (in about 20% of cases). The patient’s sputum may also be copious, foul smelling, and purulent. He may exhibit a chronic cough, coarse crackles, clubbing (a late sign), a fever, weight loss, fatigue, weakness, malaise, and dyspnea on exertion.

Bronchitis (chronic). The first sign of chronic bronchitis is typically a productive cough that lasts at least 3 months. Eventually, this leads to the production of blood-streaked sputum; massive hemorrhage is unusual. Other respiratory effects include dyspnea, prolonged expirations, wheezing, scattered rhonchi, accessory muscle use, barrel chest, tachypnea, and clubbing (a late sign).

Coagulation disorders. Such disorders as thrombocytopenia and disseminated intravascular coagulation can cause hemoptysis. Besides their specific related findings, these disorders may share such general signs as multisystem hemorrhaging (for example, GI bleeding or epistaxis) and purpuric lesions.

Lung abscess. In about 50% of patients, lung abscess produces blood-streaked sputum resulting from bronchial ulceration, necrosis, and granulation tissue. Common associated findings include a cough with large amounts of purulent, foul-smelling sputum; a fever with chills; diaphoresis; anorexia; weight loss; a headache; weakness; dyspnea; pleuritic or dull chest pain; and clubbing. Auscultation reveals tubular or cavernous breath sounds and crackles. Percussion reveals dullness on the affected side.

Lung cancer. Ulceration of the bronchus commonly causes recurring hemoptysis (an early sign), which can vary from blood-streaked sputum to blood. Related findings include a productive cough, dyspnea, a fever, anorexia, weight loss, wheezing, and chest pain (a late symptom).

Plague (Yersinia pestis) . The pneumonic form of this acute bacterial infection can produce hemoptysis, a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency, along with the sudden onset of chills, a fever, a headache, and myalgia.

Pneumonia. In up to 50% of cases, Klebsiella pneumonia produces dark brown or red (currant jelly) sputum, which is so tenacious that the patient has difficulty expelling it from his mouth. This type of pneumonia begins abruptly with chills, a fever, dyspnea, a productive cough, and severe pleuritic chest pain. Associated findings may include cyanosis, prostration, tachycardia, decreased breath sounds, and crackles.

Pneumococcal pneumonia causes pinkish or rusty mucoid sputum. It begins with sudden, shaking chills; a rapidly rising temperature; and, in over 80% of cases, tachycardia and tachypnea. Within a few hours, the patient typically experiences a productive cough along with severe, stabbing, pleuritic pain. The agonizing chest pain leads to rapid, shallow, grunting respirations with splinting. Examination reveals respiratory distress with dyspnea and accessory muscle use, crackles, and dullness on percussion over the affected lung. Malaise, weakness, myalgia, and prostration accompany a high fever.

Pulmonary edema. Severe cardiogenic or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema commonly causes

frothy, blood-tinged pink sputum, which accompanies severe dyspnea, orthopnea, gasping, anxiety, cyanosis, diffuse crackles, a ventricular gallop, and cold, clammy skin. This lifethreatening condition may also cause tachycardia, lethargy, cardiac arrhythmias, tachypnea, hypotension, and a thready pulse.

Pulmonary embolism with infarction. Hemoptysis is a common finding in pulmonary embolism with infarction, a life-threatening disorder, although massive hemoptysis is infrequent. Typical initial symptoms are dyspnea and anginal or pleuritic chest pain. Other common clinical features include tachycardia, tachypnea, a low-grade fever, and diaphoresis. Less commonly, splinting of the chest, leg edema, and — with a large embolus — cyanosis, syncope, and jugular vein distention may occur. Examination reveals decreased breath sounds, a pleural friction rub, crackles, diffuse wheezing, dullness on percussion, and signs of circulatory collapse (a weak, rapid pulse; hypotension), cerebral ischemia (transient loss of consciousness, convulsions), and hypoxemia (restlessness and, particularly in elderly patients, hemiplegia and other focal neurologic deficits).

Pulmonary hypertension (primary). Features generally develop late. Hemoptysis, exertional dyspnea, and fatigue are common. Angina-like pain usually occurs with exertion and may radiate to the neck but not to the arms. Other findings include arrhythmias, syncope, a cough, and hoarseness.

Pulmonary TB. Blood-streaked or blood-tinged sputum commonly occurs in pulmonary TB; massive hemoptysis may occur in advanced cavitary TB. Accompanying respiratory findings include a chronic productive cough, fine crackles after coughing, dyspnea, dullness on percussion, increased tactile fremitus, and possible amphoric breath sounds. The patient may also develop night sweats, malaise, fatigue, a fever, anorexia, weight loss, and pleuritic chest pain.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In 50% of patients with SLE, pleuritis and pneumonitis cause hemoptysis, a cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and crackles. Related findings are a butterfly rash in the acute phase, nondeforming joint pain and stiffness, photosensitivity, Raynaud’s phenomenon, seizures or psychoses, anorexia with weight loss, and lymphadenopathy.

Tracheal trauma. Torn tracheal mucosa may cause hemoptysis, hoarseness, dysphagia, neck pain, airway occlusion, and respiratory distress.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Lung or airway injury from bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy, mediastinoscopy, or lung biopsy can cause bleeding and hemoptysis.

Special Considerations

Comfort and reassure the patient, who may react to this alarming sign with anxiety and apprehension. If necessary, to protect the nonbleeding lung, place him in the lateral decubitus position, with the suspected bleeding lung facing down. Perform this maneuver with caution because hypoxemia may worsen with the healthy lung facing up.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests to determine the cause of bleeding. These may include a complete blood count, a sputum culture and smear, chest X-rays, coagulation studies, bronchoscopy,

lung biopsy, pulmonary arteriography, and a lung scan.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of reporting recurrent episodes. Give the patient instructions for providing sputum samples.

Pediatric Pointers

Hemoptysis in children may stem from Goodpasture’s syndrome, cystic fibrosis, or (rarely) idiopathic primary pulmonary hemosiderosis. Sometimes no cause can be found for pulmonary hemorrhage occurring within the first 2 weeks of life; in such cases, the prognosis is poor.

Geriatric Pointers

If the patient is receiving anticoagulants, determine any changes that need to be made in his diet or medications (including over-the-counter and natural supplements) because these factors may affect clotting.

REFERENCES

Menchini, L. , Remy-Jardin, M. , Faivre, J. B., Copin, M. C., Ramon, P. , Matran, R., … Remy, J. (2009) . Cryptogenic hemoptysis in smokers: Angiography and results of embolization in 35 patients. European Respiratory Journal, 34 (5), 1031–1039.

Shigemura, N., Wan, I. Y. , Yu, S. C. , Wong, R. H., Hsin, M. K., Thung, H. K., … Yim, A. P. (2009). Multidisciplinary management of life-threatening massive hemoptysis: A 10 year experience. Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 87, 849–853.

Hepatomegaly

Hepatomegaly, an enlarged liver, indicates potentially reversible primary or secondary liver disease. This sign may stem from diverse pathophysiologic mechanisms, including dilated hepatic sinusoids (in heart failure), persistently high venous pressure leading to liver congestion (in chronic constrictive pericarditis), dysfunction and engorgement of hepatocytes (in hepatitis), fatty infiltration of parenchymal cells causing fibrous tissue (in cirrhosis), distention of liver cells with glycogen (in diabetes), and infiltration of amyloid (in amyloidosis).

Hepatomegaly may be confirmed by palpation, percussion, or radiologic tests. It may be mistaken for displacement of the liver by the diaphragm, in a respiratory disorder; by an abdominal tumor; by a spinal deformity, such as kyphosis; by the gallbladder; or by fecal material or a tumor in the colon.

History and Physical Examination

Hepatomegaly is seldom a patient’s chief complaint. It usually comes to light during palpation and percussion of the abdomen.

If you suspect hepatomegaly, ask the patient about his use of alcohol and exposure to hepatitis. Also ask if he’s currently ill or taking any prescribed drugs. If he complains of abdominal pain, ask him to locate and describe it.

Inspect the patient’s skin and sclera for jaundice, dilated veins (suggesting generalized congestion), scars from previous surgery, and spider angiomas (commonly occurring in cirrhosis). Next, inspect the contour of his abdomen. Is it protuberant over the liver or distended (possibly from

ascites)? Measure his abdominal girth.

Percuss the liver, but be careful to identify structures and conditions that can obscure dull percussion notes, such as the sternum, ribs, breast tissue, pleural effusions, and gas in the colon. (See Percussing for Liver Size and Position, page 400.) Next, during deep inspiration, palpate the liver’s edge; it’s tender and rounded in hepatitis and cardiac decompensation, rocklike in carcinoma, and firm in cirrhosis.

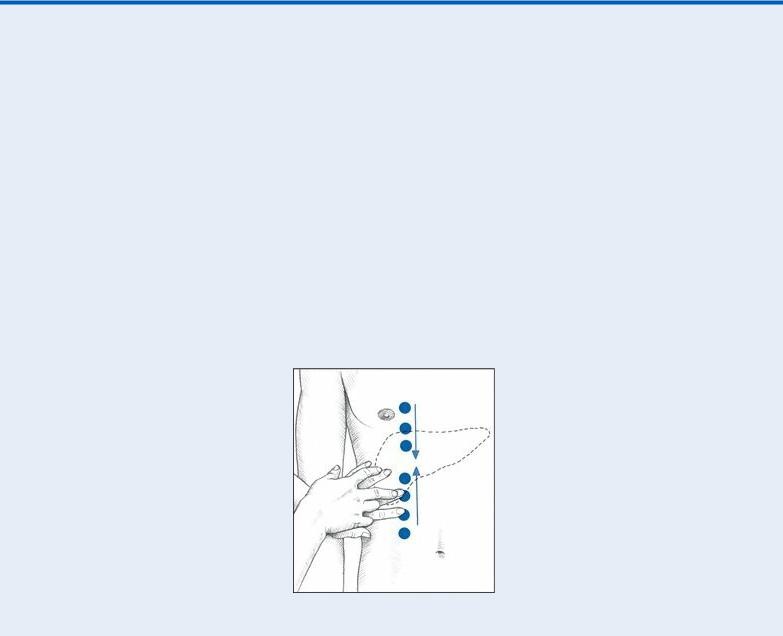

EXAMINATION TIP Percussing for Liver Size and Position

EXAMINATION TIP Percussing for Liver Size and Position

With the patient in a supine position, begin at the right iliac crest to percuss up the right midclavicular line (MCL), as shown below. The percussion note becomes dull when you reach the liver’s inferior border — usually at the costal margin, but sometimes at a lower point in a patient with liver disease. Mark this point and then percuss down from the right clavicle, again along the right MCL. The liver’s superior border usually lies between the fifth and seventh intercostal spaces. Mark the superior border.

The distance between the two marked points represents the approximate span of the liver’s right lobe, which normally ranges from 2¼” to 4¾” (6 to 12 cm).

Next, assess the liver’s left lobe similarly, percussing along the sternal midline. Again, mark the points where you hear dull percussion notes. Also, measure the span of the left lobe, which normally ranges from 1½” to 3⅛” (4 to 8 cm). Record your findings for use as a baseline.

Take the patient’s baseline vital signs, and assess his nutritional status. An enlarged liver that’s functioning poorly causes muscle wasting, exaggerated skeletal prominences, weight loss, thin hair, and edema.

Evaluate the patient’s level of consciousness. When an enlarged liver loses its ability to detoxify waste products, the result is accumulation of metabolic substances toxic to brain cells. As a result, watch for personality changes, irritability, agitation, memory loss, an inability to concentrate and poor mentation, and — in a severely ill patient — coma.

Medical Causes

Amyloidosis. Amyloidosis is a rare disorder that may cause hepatomegaly and mild jaundice as well as renal, cardiac, and other GI effects.

Cirrhosis. Late in cirrhosis, the liver becomes enlarged, nodular, and hard. Other late signs and symptoms affect all body systems. Respiratory findings include limited thoracic expansion due to abdominal ascites, leading to hypoxia. Central nervous system findings include signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, such as lethargy, slurred speech, asterixis, peripheral neuritis, paranoia, hallucinations, extreme obtundation, and coma. Hematologic signs include epistaxis, easy bruising, and bleeding gums. Endocrine findings include testicular atrophy, gynecomastia, loss of chest and axillary hair, or menstrual irregularities. Integumentary effects include abnormal pigmentation, jaundice, severe pruritus, extreme dryness, poor tissue turgor, spider angiomas, and palmar erythema.

The patient may also develop fetor hepaticus, enlarged superficial abdominal veins, muscle atrophy, right upper quadrant pain that worsens when he sits up or leans forward, and a palpable spleen. Portal hypertension — elevated pressure in the portal vein — causes bleeding from esophageal varices.

Diabetes mellitus. Poorly controlled diabetes in overweight patients commonly produces fatty infiltration of the liver, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness along with polydipsia, polyphagia, and polyuria. These features are more common in type 2 than in type 1 diabetes. A chronically enlarged fatty liver typically produces no symptoms except for slight tenderness.

Granulomatous disorders. Sarcoidosis, histoplasmosis, and other such disorders commonly produce a slightly enlarged, firm liver.

Hepatic abscess. Hepatomegaly may accompany a fever (a primary sign), nausea, vomiting, chills, weakness, diarrhea, anorexia, an elevated right hemidiaphragm, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness.

Hepatitis. In viral hepatitis, early signs and symptoms include nausea, anorexia, vomiting, fatigue, malaise, photophobia, a sore throat, a cough, and a headache. Hepatomegaly occurs in the icteric phase and continues during the recovery phase. Also, during the icteric phase, the early signs and symptoms diminish and others appear: liver tenderness, slight weight loss, dark urine, clay-colored stools, jaundice, pruritus, right upper quadrant pain, and splenomegaly.

Leukemia and lymphomas. Leukemia and lymphomas are proliferative blood cell disorders that typically cause moderate to massive hepatomegaly and splenomegaly as well as abdominal discomfort. General signs and symptoms include malaise, a low-grade fever, fatigue, weakness, tachycardia, weight loss, bleeding disorders, and anorexia.

Liver cancer. Primary tumors commonly cause irregular, nodular, firm hepatomegaly, with pain or tenderness in the right upper quadrant and a friction rub or bruit over the liver. Common related findings are weight loss, anorexia, cachexia, nausea, and vomiting. Peripheral edema, ascites, jaundice, and a palpable right upper quadrant mass may also develop. When metastatic liver tumors cause hepatomegaly, the patient’s accompanying signs and symptoms reflect his primary cancer.

Mononucleosis (infectious). Occasionally, infectious mononucleosis causes hepatomegaly. Prodromal symptoms include a headache, malaise, and fatigue. After 3 to 5 days, the patient typically develops a sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, and temperature fluctuations. He may also develop stomatitis, palatal petechiae, periorbital edema, splenomegaly, exudative tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and, possibly, a maculopapular rash.