- •Textbook Series

- •Contents

- •1 Basic Concepts

- •The History of Human Performance

- •The Relevance of Human Performance in Aviation

- •ICAO Requirement for the Study of Human Factors

- •The Pilot and Pilot Training

- •Aircraft Accident Statistics

- •Flight Safety

- •The Most Significant Flight Safety Equipment

- •Safety Culture

- •Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model

- •The Five Elements of Safety Culture

- •Flight Safety/Threat and Error Management

- •Threats

- •Errors

- •Undesired Aircraft States

- •Duties of Flight Crew

- •2 The Circulation System

- •Blood Circulation

- •The Blood

- •Composition of the Blood

- •Carriage of Carbon Dioxide

- •The Circulation System

- •What Can Go Wrong

- •System Failures

- •Factors Predisposing to Heart Attack

- •Insufficient Oxygen Carried

- •Carbon Monoxide

- •Smoking

- •Blood Pressure

- •Pressoreceptors and their Function Maintaining Blood Pressure

- •Function

- •Donating Blood and Aircrew

- •Pulmonary Embolism

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •3 Oxygen and Respiration

- •Oxygen Intake

- •Thresholds of Oxygen Requirements Summary

- •Hypoxic Hypoxia

- •Hypoxic Hypoxia Symptoms

- •Stages/Zones of Hypoxia

- •Factors Determining the Severity of and the Susceptibility to Hypoxic Hypoxia

- •Anaemic Hypoxia

- •Time of Useful Consciousness (TUC)

- •Times of Useful Consciousness at Various Altitudes

- •Effective Performance Time (EPT)

- •Hyperventilation

- •Symptoms of Hyperventilation

- •Hypoxia or Hyperventilation?

- •Cabin Pressurization

- •Cabin Decompression

- •Decompression Sickness (DCS)

- •DCS in Flight and Treatment

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •4 The Nervous System, Ear, Hearing and Balance

- •Introduction

- •The Nervous System

- •The Sense Organs

- •Audible Range of the Human Ear and Measurement of Sound

- •Hearing Impairment

- •The Ear and Balance

- •Problems of Balance and Disorientation

- •Somatogyral and Somatogravic Illusions

- •Alcohol and Flying

- •Motion Sickness

- •Coping with Motion Sickness

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •5 The Eye and Vision

- •Function and Structure

- •The Cornea

- •The Iris and Pupil

- •The Lens

- •The Retina

- •The Fovea and Visual Acuity

- •Light and Dark Adaptation

- •Night Vision

- •The Blind Spot

- •Stereopsis (Stereoscopic Vision)

- •Empty Visual Field Myopia

- •High Light Levels

- •Sunglasses

- •Eye Movement

- •Visual Defects

- •Use of Contact Lenses

- •Colour Vision

- •Colour Blindness

- •Vision and Speed

- •Monocular and Binocular Vision

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •6 Flying and Health

- •Flying and Health

- •Acceleration

- •G-forces

- •Effects of Positive G-force on the Human Body

- •Long Duration Negative G

- •Short Duration G-forces

- •Susceptibility and Tolerance to G-forces

- •Summary of G Tolerances

- •Barotrauma

- •Toxic Hazards

- •Body Mass Index (BMI)

- •Obesity

- •Losing Weight

- •Exercise

- •Nutrition and Food Hygiene

- •Fits

- •Faints

- •Alcohol and Alcoholism

- •Alcohol and Flying

- •Drugs and Flying

- •Psychiatric Illnesses

- •Diseases Spread by Animals and Insects

- •Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- •Personal Hygiene

- •Stroboscopic Effect

- •Radiation

- •Common Ailments and Fitness to Fly

- •Drugs and Self-medication

- •Anaesthetics and Analgesics

- •Symptoms in the Air

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •7 Stress

- •An Introduction to Stress

- •The Stress Model

- •Arousal and Performance

- •Stress Reaction and the General Adaption Syndrome (GAS)

- •Stress Factors (Stressors)

- •Physiological Stress Factors

- •External Physiological Factors

- •Internal Physiological Factors

- •Cognitive Stress Factors/Stressors

- •Non-professional Personal Factors/Stressors

- •Stress Table

- •Imaginary Stress (Anxiety)

- •Organizational Stress

- •Stress Effects

- •Coping with Stress

- •Coping with Stress on the Flight Deck

- •Stress Management Away from the Flight Deck

- •Stress Summary

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •Introduction

- •Basic Information Processing

- •Stimuli

- •Receptors and Sensory Memories/Stores

- •Attention

- •Perception

- •Perceived Mental Models

- •Three Dimensional Models

- •Short-term Memory (Working Memory)

- •Long-term Memory

- •Central Decision Maker and Response Selection

- •Motor Programmes (Skills)

- •Human Reliability, Errors and Their Generation

- •The Learning Process

- •Mental Schema

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •9 Behaviour and Motivation

- •An Introduction to Behaviour

- •Categories of Behaviour

- •Evaluating Data

- •Situational Awareness

- •Motivation

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •10 Cognition in Aviation

- •Cognition in Aviation

- •Visual Illusions

- •An Illusion of Movement

- •Other Sources of Illusions

- •Illusions When Taxiing

- •Illusions on Take-off

- •Illusions in the Cruise

- •Approach and Landing

- •Initial Judgement of Appropriate Glideslope

- •Maintenance of the Glideslope

- •Ground Proximity Judgements

- •Protective Measures against Illusions

- •Collision and the Retinal Image

- •Human Performance Cognition in Aviation

- •Special Situations

- •Spatial Orientation in Flight and the “Seat-of-the-pants”

- •Oculogravic and Oculogyral Illusions

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •11 Sleep and Fatigue

- •General

- •Biological Rhythms and Clocks

- •Body Temperature

- •Time of Day and Performance

- •Credit/Debit Systems

- •Measurement and Phases of Sleep

- •Age and Sleep

- •Naps and Microsleeps

- •Shift Work

- •Time Zone Crossing

- •Sleep Planning

- •Sleep Hygiene

- •Sleep and Alcohol

- •Sleep Disorders

- •Drugs and Sleep Management

- •Fatigue

- •Vigilance and Hypovigilance

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •12 Individual Differences and Interpersonal Relationships

- •Introduction

- •Personality

- •Interactive Style

- •The Individual’s Contribution within a Group

- •Cohesion

- •Group Decision Making

- •Improving Group Decision Making

- •Leadership

- •The Authority Gradient and Leadership Styles

- •Interacting with Other Agencies

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •13 Communication and Cooperation

- •Introduction

- •A Simple Communications Model

- •Types of Questions

- •Communications Concepts

- •Good Communications

- •Personal Communications

- •Cockpit Communications

- •Professional Languages

- •Metacommunications

- •Briefings

- •Communications to Achieve Coordination

- •Synchronization

- •Synergy in Joint Actions

- •Barriers to Crew Cooperation and Teamwork

- •Good Team Work

- •Summary

- •Miscommunication

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •14 Man and Machine

- •Introduction

- •The Conceptual Model

- •Software

- •Hardware and Automation

- •Intelligent Flight Decks

- •Colour Displays

- •System Active and Latent Failures/Errors

- •System Tolerance

- •Design-induced Errors

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •15 Decision Making and Risk

- •Introduction

- •The Mechanics of Decision Making

- •Standard Operating Procedures

- •Errors, Sources and Limits in the Decision-making Process

- •Personality Traits and Effective Crew Decision Making

- •Judgement Concept

- •Commitment

- •Questions

- •Answers

- •16 Human Factors Incident Reporting

- •Incident Reporting

- •Aeronautical Information Circulars

- •Staines Trident Accident 1972

- •17 Introduction to Crew Resource Management

- •Introduction

- •Communication

- •Hearing Versus Listening

- •Question Types

- •Methods of Communication

- •Communication Styles

- •Overload

- •Situational Awareness and Mental Models

- •Decision Making

- •Personality

- •Where We Focus Our Attention

- •How We Acquire Information

- •How We Make Decisions

- •How People Live

- •Behaviour

- •Modes of Behaviour

- •Team Skill

- •18 Specimen Questions

- •Answers to Specimen Papers

- •Revision Questions

- •Answers to Revision Questions

- •Specimen Examination Paper

- •Answers to Specimen Examination Paper

- •Explanations to Specimen Examination Paper

- •19 Glossary

- •Glossary of Terms

- •20 Index

Chapter

16

Human Factors Incident Reporting

Incident Reporting . . . . . . . . |

. . |

. . |

. . |

. . |

. . . . . . . . |

. . |

. |

311 |

Aeronautical Information Circulars . . |

. . |

. . |

. . |

. . |

. . . . . . . . |

. . |

. |

316 |

Staines Trident Accident 1972 . . . . |

. . |

. . |

. . |

. . |

. . . . . . . . |

. . |

. |

316 |

309

16 Human Factors Incident Reporting

Reporting Incident Factors Human 16

310

Human Factors Incident Reporting 16

Incident Reporting

Introduction

It was first calculated in 1940 that three out of four aircraft accidents are due to what has been called human failure of one kind or another. This figure was confirmed by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) thirty five years later. During the year that IATA was publishing its figures (1977) two aircraft collided at Tenerife with a cost of 583 lives and about £100 million, creating the greatest disaster in aviation history and resulting entirely from a series of human factor deficiencies. Today it is calculated that over 70% of all civilian aircraft accidents are the result of human error of some kind.

Reporting Schemes

In an effort to publicise the human factor in aviation accidents, various reporting schemes have been established which allow not only pilots but other agencies, such as Air Traffic Controllers, to report anonymously incidents in which human factors have been a contributing, if not sole, cause.

The first scheme was established by NASA in 1976 and was called The Confidential Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS). This recognized, for the first time, that it is unrealistic to expect to obtain adequate information for analysis of human behaviour and lapses in human performance while, at the same time, holding the threat of punitive action against those making the reports. This change of attitude was justified by the accumulation in the first ten years of operation, of a data bank of more than 52 000 reports. During 1985 alone, 9280 reports reached the ASRS offices at NASA, the majority from airline pilots.

Some six years after the ASRS programme was set up a similar scheme, the Confidential Human Factors Incident Reporting Programme (CHIRP) was initiated in the UK. Canada and Australia have similar schemes.

The CHIRP Programme

The CHIRP programme allows civilian pilots and other crew members to submit confidential reports to the Royal Air Force Institute of Aviation Medicine. Reports are issued at regular intervals in the bulletin ‘Feedback’ which is readily available to all in the aviation world.

Selected extracts from CHIRP reports are reproduced below and other examples will be used during the lesson periods. The scope of the reports are wide and cover all facets of operating aircraft, crew fatigue, poorly designed equipment, communication problems and interpersonal relationships.

CHIRP Report 1 (Cockpit Design)

‘For the third time, I was caught by variations of switch position on our F27s. During the after start checks, the F/O put the water-methanol switches on instead of the pitot heaters. On some aircraft these switch positions are exchanged. As full power was achieved, I was surprised to hear water-methanol flow cutting in (my own taxi checks having failed to spot the ergonomically induced error)....I know that others have made this error several times, though not usually reaching the take-off stage.’

CHIRP Report 2 (Cockpit Design)

‘On intermediate approach, while moving his hand from the VHF frequency selector switch on the central pedestal to the heading select knob on the glare shield, the captain’s right knuckle contacted the go-around button on the left thrust lever - with the expected result.’

Human Factors Incident Reporting 16

311

16

Reporting Incident Factors Human 16

Human Factors Incident Reporting

CHIRP Report 3 (Cockpit Design)

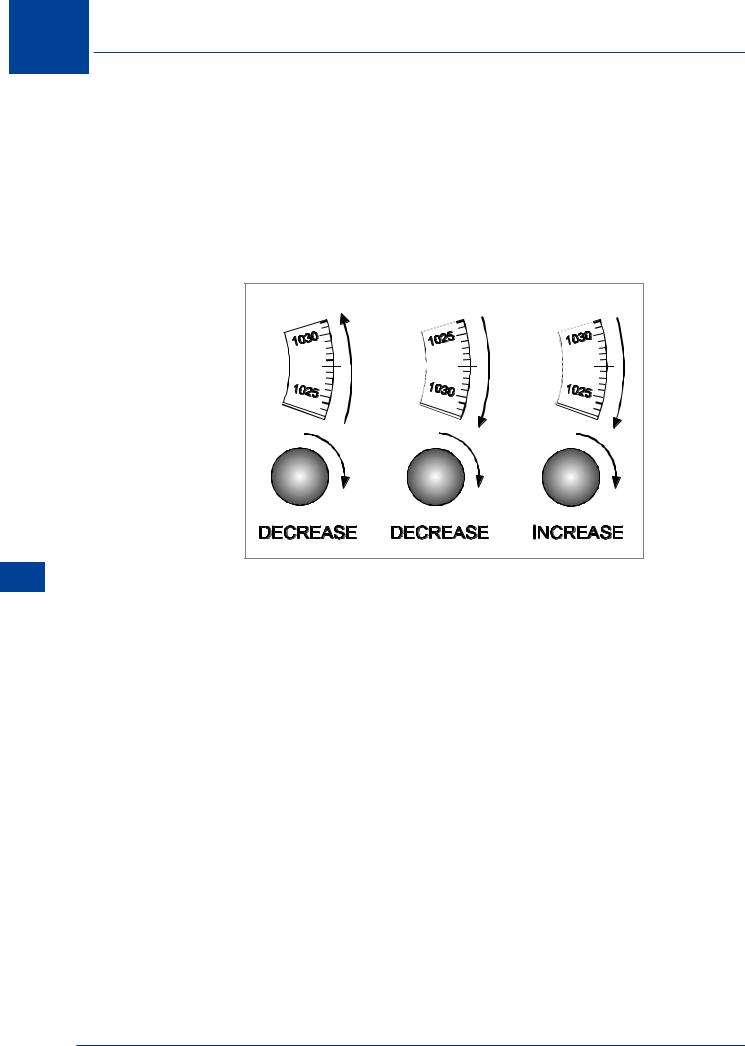

‘......while I set the QFE and promptly commenced the descent to 2000 ft QFE.... At 2000 ft my co-pilot said ‘You’ve gone below 2000 ft.’ I replied that I had not, but then saw that my altimeter was set on 1030 mb and not the correct QFE of 1020 mb. Consider Figure 16.1 below which is drawn to actual size. The altimeters are viewed from a distance of some 50 cm, while the instrument panel is acknowledged to suffer from shake. The individual helicopters are fitted with altimeters of types A and C, or B and C. As the pilots fly from either seat, a pilot may find himself using an instrument of any type. It seems that most of my colleagues have difficulty in seeing and setting the correct pressures.

Figure 16.1 Altimeter control - display relationships

CHIRP Report 4 (Status and Role)

The twin prop commuter aircraft was commanded by a pilot who was also a senior manager in the airline and known to be somewhat irascible. The first officer was junior in the company and still in his probation period. It was the end of an already long day, and the captain was plainly annoyed when the company operations asked for a further flight, but he reluctantly undertook it. During the approach at end of this leg, the first officer went through the approach checks but received no response at all from the captain. Rather than question or challenge the captain, the first officer sat tight and let the captain get on with it. The aircraft flew into the ground short of the runway because the first officer did nothing to intervene. It transpired that the captain had failed to respond to the checks not because he was in a bad mood but because he had died during the approach.

CHIRP Report 5 (Risky Shift)

‘Following about two weeks of IMC in an Aberdeen winter both of us (Co and myself) were gripped by an overwhelming desire to SEE something other than white mist. Between rigs, with cloud base at destination known to be at 200 ft. No problem, but IMC at the time. Tell FO to set Rad Alt bug at 100 ft - set the Radar on 5 miles scale and tell me if any hard bits show up. I then start a descent to regain VMC. Still no sign of the sea at 200 ft. Keep on going down slowly. Radar screen still clear. Keep descending, well below limits but have to actually get to SEE again, and after all this is the North Sea where men are men, etc etc. We actually level out at 75 ft, but still IMC but can see the waves below. No problem as you never come across 75 ft waves. Decca playing up and became engrossed in navigation problem, radio calls, and an intermittent engine “ANTI-ICE” caption.

312

Human Factors Incident Reporting 16

Co-pilot suddenly points to radar screen and says “What’s that?”. Large blob on bottom of screen (i.e. about ten feet in front of us). Haul back on stick - haul up on collective - heart stopping few seconds waiting for massive lump of machinery to appear in front of us. Needless to say we missed it - whatever it was - didn’t even see it; bet we gave them a fright though.

CHIRP Report 6 (Sleep and Fatigue)

The aircraft left base as an evening flight delayed about 45 minutes for some of the usual reasons. Scheduled to wait in Greece for some three hours so as not to arrive back before the end of the night curfew. Departure for return flight arranged so as to be in the queue early enough to be actually landing as close as possible to scheduled landing time of arrival.

On first calling Gatwick approach, it was number 8 to land, gradually descending in the hold as others left the stack. During the second hold, the aircraft descended on autopilot to FL 070 and the handling pilot opened the throttles (no auto-throttle) to maintain holding speed inbound to the fix. He woke up again almost two miles beyond the fix where he should have turned.

CHIRP Report 7 (Sleep and Fatigue, Chapter 10)

‘The previous day I operated a flight of 13 hr 45 min duty, 10 hrs flying. Arrived back at base at approximately 0815 local time having departed at 1810 the previous evening. Our local regulations are that for flights departing between 6.00am and 6.00pm - 13.45 duty. For flights scheduled to depart 6.00pm to 6.00am - 12 hours duty. By changing the departure to 1755 it thus becomes a DAYLIGHT flight! The next night I was rostered for a flight leaving base at 1.00am and five hours flight time. Very little sleep during the day due to poor facilities and thin curtains. During the flight I informed the F/O and S/O that I wanted 10 minutes rest - eyes shut. I opened my eyes 3 MINS later to find both the F/O and S/O sound asleep! Had I fallen asleep the results could have been disastrous.

CHIRP Report 8 (Divided Attention)

‘A nice day - no weather problems and a fully serviceable a/c. At rotate on the previous sector I noticed an amber leading edge flap warning light flash on for a second. This is normally caused by a slightly misaligned proximity switch.

On the next take-off, with the F/O flying, I watched the flap warning light carefully for a recurrence of the fault. After rotate the F/O called for ‘gear up’ and I reached for the Flap Lever. The F/O called out, I realized what I was doing and slipped the Flap Lever back into the detent.

I thanked the F/O and my lucky stars and vowed never again to allow minor fault diagnosis to distract me from the task in hand.

CHIRP Report 9 (Expectation)

‘........ we were now right on departure time so I glanced at the fuel gauges, “saw” what I expected to see and signed the Tech Log and Ships Papers.

At the top of the climb a fuel check revealed a large discrepancy and a check of the Tech Log showed that I had signed for 6000 kg although the Ships Papers showed 8000 kg as requested. We reduced to economy cruise speed and a detailed fuel check showed that we could reach ‘A’ with fuel to divert to ‘B’ plus reserve. The weather at ‘A’ and ‘B’ was improving and ATC reported no delays into ‘A’ so I decided to continue. We arrived on stand at ‘A’ with diversion and reserve fuel plus about 130 kg.

Human Factors Incident Reporting 16

313

16 Human Factors Incident Reporting

CHIRP Report 10 (Cockpit Design)

Taxiing out from dispersal we had reached the point in the check list for “Flap Selection”. The captain confirmed flap to go to take off so I put my left hand down, grasped the knob and pushed downwards. Its travel felt remarkably smooth, so I looked down to find I had actually closed the No 2 HP cock shutting the engine down. The top of the flap lever and the HP cock are immediately next to each other.

Only a small incident and not much more than highly embarrassing but it might have been different if we had been on the approach.

CHIRP Report 11 (Automated Controls)

Throughout the descent we all assumed the Auto Throttle System (ATS) was engaged. Although we all checked the correct speeds were set ‘in the window’ we ALL missed the fact that the ATS was not engaged. Having captured the Localizer and levelling off at 4500 ft to capture the Glideslope the speed was allowed, inadvertently, to drop 10 - 15 kt BELOW MIN SPEED! On noticing the speed I applied Max thrust and prevented the aircraft from stalling.

I know of 2 other similar cases concerning different crews and told to me confidentially. It’s apparent, to me, that we rely rather heavily on the autothrottle system and it only takes the assumption that ATS is engaged and a distraction on the flight deck to set up a potentially dangerous situation.

Reporting Incident Factors Human 16

CHIRP Report 13 (Flying and Health)

On the climb to FL80 I suddenly started to feel unwell, with stomach pains and an urgent desire to defecate. It soon became obvious that I was suffering from an attack of diarrhoea. To divert back to ********* to go to the toilet would have incurred serious commercial penalties and, no doubt, very little sympathy from the company’s management. I therefore decided to persevere and continue to *****. Fortunately the weather was good and I was able to complete a straight in, visual approach. During the second half of the flight the quality of my flying had deteriorated significantly, and my pre-landing checks consisted of little more than checking “Three green lights and brakes off,” before closing the throttles and landing. I made it to the toilet, just in time, and was able to continue the rest of my night’s flying without incident.

Most of my commercial flying has been single crew and it is a type of flying I have always enjoyed. Pilot incapacitation is something I have always considered as so remote a possibility in someone of my age, that I have previously ignored it, confining it to pilots with “dicky tickers” who are nearing retirement. However, the sort of incapacitation that I suffered in this incident had a markedly adverse effect on the safety of the flight, and it has called into question, in my own mind, the whole desirability of operating public transport flights, single crew.

CHIRP Report 14 (Flying and Health)

I was flying the aircraft back to Luton at the end of a long and frustrating day where I’d been on duty for approximately 13 hours.

The Captain was a heavy smoker and the flight deck had been occupied for most of the sector by a third person who also smoked heavily. During the intermediate approach phase I’d noticed that my instrument flying was a little sloppy. I conducted a visual final approach in almost perfect, calm conditions. During the approach I had the greatest difficulty in maintaining a reasonable glide path on the VASIS and also in maintaining the centreline. My response to deviations were late and sluggish. My landing was poor and well off the runway centreline.

314

Human Factors Incident Reporting 16

After long deliberations I can only reach the conclusion that, as a non-smoker, I had been adversely affected by the smoking to the extent that my ability and judgement had been seriously impaired.

CHIRP Report 15 (Personality)

Two senior Captains flying a medium sized passenger aircraft returning to the UK.

Other Captain’s leg, ex-fighter pilot, never forgot it. Also training Captain and always trying to catch out co-capt, always had superior equipment, watch, calculator etc. On arrival I passed him the weather with the comment “You won’t like it”. The weather was poor with strong cross winds.

At the marker we were badly placed and too high, I suggested “Full power for overshoot”. He said “Negative”, closed the throttles, increased flap and continued with the landing. We hit first on port main wheel and wing tip, then I heard the crunch as port engine struck the ground. He called for full power but I held throttles tightly closed knowing the aircraft was structurally damaged. Further damage occurred before we came to a halt.

My mistake was not being more forceful when it was quite obvious that a safe landing was impossible. His subsequent attitude was that if I had obeyed his instructions and given him full power he would have been able to take off again.

CHIRP Report 16 (Visual Illusions)

In the descent to our destination airfield at night the weather being reported good, we requested a visual LH circuit to R/W 29. Whilst attempting to keep the runway in sight, unreported stratus was encountered over the sea. The aircraft descended to beneath the cloud and the R/W looked for to the left. The GPWS triggered but positive action was not taken because the surface of the sea could be seen and looked OK. This caused us to misread our altimeters and mistake 200 feet QFE for 1200 feet QFE. We were still some way from the airfield and heading for rising ground. Fortunately we realized our mistake and rapidly climbed to a safe height.

CHIRP Report 17 (Illusions)

In the cruise, VMC on top in bright sunshine, blade flash through the front rotor system onto the flight deck caused a feeling of unease and tension. After about 45 minutes I left the flight deck and obtained a baseball cap from my nav bag and returned to the flight deck, the symptoms immediately began to subside and disappeared totally within 10 minutes.

This problems has occurred before when I didn’t have a cap available and the problem continued until I either descended below cloud or completed the flight.

The above reports have been selected from CHIRPs reports over the last ten years. For a fuller review of these reports your instructor will have available all the reports issued over that period. Many of the incidents reported have happened to very senior, experienced pilots. It is not only inexperienced pilots who make human errors. Anyone, when they are tired, under stress, unwell or simply not paying attention can make mistakes.

DON’T LET IT BE YOU!

Human Factors Incident Reporting 16

315