- •Contents

- •1 Russian

- •1.1 The Russian language

- •1.1.1 Russian then and now

- •1.1.2 Levels of language

- •1.2 Describing Russian grammar

- •1.2.1 Conventions of notation

- •1.2.2 Abbreviations

- •1.2.3 Dictionaries and grammars

- •1.2.4 Statistics and corpora

- •1.2.5 Strategies of describing Russian grammar

- •1.2.6 Two fundamental concepts of (Russian) grammar

- •1.3 Writing Russian

- •1.3.1 The Russian Cyrillic alphabet

- •1.3.2 A brief history of the Cyrillic alphabet

- •1.3.3 Etymology of letters

- •1.3.4 How the Cyrillic alphabet works (basics)

- •1.3.5 How the Cyrillic alphabet works (refinements)

- •1.3.6 How the Cyrillic alphabet works (lexical idiosyncrasies)

- •1.3.7 Transliteration

- •2 Sounds

- •2.1 Sounds

- •2.2 Vowels

- •2.2.1 Stressed vowels

- •2.2.3 Vowel duration

- •2.2.4 Unstressed vowels

- •2.2.5 Unpaired consonants [ˇs ˇz c] and unstressed vocalism

- •2.2.6 Post-tonic soft vocalism

- •2.2.7 Unstressed vowels in sequence

- •2.2.8 Unstressed vowels in borrowings

- •2.3 Consonants

- •2.3.1 Classification of consonants

- •2.3.2 Palatalization of consonants

- •2.3.3 The distribution of palatalized consonants

- •2.3.4 Palatalization assimilation

- •2.3.5 The glide [j]

- •2.3.6 Affricates

- •2.3.7 Soft palatal fricatives

- •2.3.8 Geminate consonants

- •2.3.9 Voicing of consonants

- •2.4 Phonological variation

- •2.4.1 General

- •2.4.2 Phonological variation: idiomaticity

- •2.4.3 Phonological variation: systemic factors

- •2.4.4 Phonological variation: phonostylistics and Old Muscovite pronunciation

- •2.5 Morpholexical alternations

- •2.5.1 Preliminaries

- •2.5.2 Consonant grades

- •2.5.3 Types of softness

- •2.5.4 Vowel grades

- •2.5.5 Morphophonemic {o}

- •3 Inflectional morphology

- •3.1 Introduction

- •3.2 Conjugation of verbs

- •3.2.1 Verbal categories

- •3.2.2 Conjugation classes

- •3.2.3 Stress patterns

- •3.2.4 Conjugation classes: I-Conjugation

- •3.2.5 Conjugation classes: suffixed E-Conjugation

- •3.2.6 Conjugation classes: quasisuffixed E-Conjugation

- •3.2.7 Stress in verbs: retrospective

- •3.2.8 Irregularities in conjugation

- •3.2.9 Secondary imperfectivization

- •3.3 Declension of pronouns

- •3.3.1 Personal pronouns

- •3.3.2 Third-person pronouns

- •3.3.3 Determiners (demonstrative, possessive, adjectival pronouns)

- •3.4 Quantifiers

- •3.5 Adjectives

- •3.5.1 Adjectives

- •3.5.2 Predicative (‘‘short”) adjectives

- •3.5.3 Mixed adjectives and surnames

- •3.5.4 Comparatives and superlatives

- •3.6 Declension of nouns

- •3.6.1 Categories and declension classes of nouns

- •3.6.2 Hard, soft, and unpaired declensions

- •3.6.3 Accentual patterns

- •3.6.8 Declension and gender of gradation

- •3.6.9 Accentual paradigms

- •3.7 Complications in declension

- •3.7.1 Indeclinable common nouns

- •3.7.2 Acronyms

- •3.7.3 Compounds

- •3.7.4 Appositives

- •3.7.5 Names

- •4 Arguments

- •4.1 Argument phrases

- •4.1.1 Basics

- •4.1.2 Reference of arguments

- •4.1.3 Morphological categories of nouns: gender

- •4.1.4 Gender: unpaired ‘‘masculine” nouns

- •4.1.5 Gender: common gender

- •4.1.6 Morphological categories of nouns: animacy

- •4.1.7 Morphological categories of nouns: number

- •4.1.8 Number: pluralia tantum, singularia tantum

- •4.1.9 Number: figurative uses of number

- •4.1.10 Morphological categories of nouns: case

- •4.2 Prepositions

- •4.2.1 Preliminaries

- •4.2.2 Ligature {o}

- •4.2.3 Case government

- •4.3 Quantifiers

- •4.3.1 Preliminaries

- •4.3.2 General numerals

- •4.3.3 Paucal numerals

- •4.3.5 Preposed quantified noun

- •4.3.6 Complex numerals

- •4.3.7 Fractions

- •4.3.8 Collectives

- •4.3.9 Approximates

- •4.3.10 Numerative (counting) forms of selected nouns

- •4.3.12 Quantifier (numeral) cline

- •4.4 Internal arguments and modifiers

- •4.4.1 General

- •4.4.2 Possessors

- •4.4.3 Possessive adjectives of unique nouns

- •4.4.4 Agreement of adjectives and participles

- •4.4.5 Relative clauses

- •4.4.6 Participles

- •4.4.7 Comparatives

- •4.4.8 Event nouns: introduction

- •4.4.9 Semantics of event nouns

- •4.4.10 Arguments of event nouns

- •4.5 Reference in text: nouns, pronouns, and ellipsis

- •4.5.1 Basics

- •4.5.2 Common nouns in text

- •4.5.3 Third-person pronouns

- •4.5.4 Ellipsis (‘‘zero” pronouns)

- •4.5.5 Second-person pronouns and address

- •4.5.6 Names

- •4.6 Demonstrative pronouns

- •4.7 Reflexive pronouns

- •4.7.1 Basics

- •4.7.2 Autonomous arguments

- •4.7.3 Non-immediate sites

- •4.7.4 Special predicate--argument relations: existential, quantifying, modal, experiential predicates

- •4.7.5 Unattached reflexives

- •4.7.6 Special predicate--argument relations: direct objects

- •4.7.7 Special predicate--argument relations: passives

- •4.7.8 Autonomous domains: event argument phrases

- •4.7.9 Autonomous domains: non-finite verbs

- •4.7.12 Retrospective on reflexives

- •4.8 Quantifying pronouns and adjectives

- •4.8.1 Preliminaries: interrogatives as indefinite pronouns

- •4.8.7 Summary

- •4.8.9 Universal adjectives

- •5 Predicates and arguments

- •5.1 Predicates and arguments

- •5.1.1 Predicates and arguments, in general

- •5.1.2 Predicate aspectuality and modality

- •5.1.3 Aspectuality and modality in context

- •5.1.4 Predicate information structure

- •5.1.5 Information structure in context

- •5.1.6 The concept of subject and the concept of object

- •5.1.7 Typology of predicates

- •5.2 Predicative adjectives and nouns

- •5.2.1 General

- •5.2.2 Modal co-predicates

- •5.2.3 Aspectual co-predicates

- •5.2.4 Aspectual and modal copular predicatives

- •5.2.5 Copular constructions: instrumental

- •5.2.6 Copular adjectives: predicative (short) form vs. nominative (long) form

- •5.2.9 Predicatives in non-finite clauses

- •5.2.10 Summary: case usage in predicatives

- •5.3 Quantifying predicates and genitive subjects

- •5.3.1 Basics

- •5.3.2 Clausal quantifiers and subject quantifying genitive

- •5.3.3 Subject quantifying genitive without quantifiers

- •5.3.4 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: basic paradigm

- •5.3.5 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: predicates

- •5.3.6 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: reference

- •5.3.8 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: predicates and reference

- •5.3.9 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: context

- •5.3.10 Existential predication and the subject genitive of negation: summary

- •5.4 Quantified (genitive) objects

- •5.4.1 Basics

- •5.4.2 Governed genitive

- •5.4.3 Partitive and metric genitive

- •5.4.4 Object genitive of negation

- •5.4.5 Genitive objects: summary

- •5.5 Secondary genitives and secondary locatives

- •5.5.1 Basics

- •5.5.2 Secondary genitive

- •5.5.3 Secondary locative

- •5.6 Instrumental case

- •5.6.1 Basics

- •5.6.2 Modal instrumentals

- •5.6.3 Aspectual instrumentals

- •5.6.4 Agentive instrumentals

- •5.6.5 Summary

- •5.7 Case: context and variants

- •5.7.1 Jakobson’s case system: general

- •5.7.2 Jakobson’s case system: the analysis

- •5.7.3 Syncretism

- •5.7.4 Secondary genitive and secondary locative as cases?

- •5.8 Voice: reflexive verbs, passive participles

- •5.8.1 Basics

- •5.8.2 Functional equivalents of passive

- •5.8.3 Reflexive verbs

- •5.8.4 Present passive participles

- •5.8.5 Past passive participles

- •5.8.6 Passives and near-passives

- •5.9 Agreement

- •5.9.1 Basics

- •5.9.2 Agreement with implicit arguments, complications

- •5.9.3 Agreement with overt arguments: special contexts

- •5.9.4 Agreement with conjoined nouns

- •5.9.5 Agreement with comitative phrases

- •5.9.6 Agreement with quantifier phrases

- •5.10 Subordinate clauses and infinitives

- •5.10.1 Basics

- •5.10.2 Finite clauses

- •5.10.4 The free infinitive construction (without overt modal)

- •5.10.5 The free infinitive construction (with negative existential pronouns)

- •5.10.6 The dative-with-infinitive construction (overt modal)

- •5.10.7 Infinitives with modal hosts (nominative subject)

- •5.10.8 Infinitives with hosts of intentional modality (nominative subject)

- •5.10.9 Infinitives with aspectual hosts (nominative subject)

- •5.10.10 Infinitives with hosts of imposed modality (accusative or dative object)

- •5.10.11 Final constructions

- •5.10.12 Summary of infinitive constructions

- •6 Mood, tense, and aspect

- •6.1 States and change, times, alternatives

- •6.2 Mood

- •6.2.1 Modality in general

- •6.2.2 Mands and the imperative

- •6.2.3 Conditional constructions

- •6.2.4 Dependent irrealis mood: possibility, volitive, optative

- •6.2.5 Dependent irrealis mood: epistemology

- •6.2.6 Dependent irrealis mood: reference

- •6.2.7 Independent irrealis moods

- •6.2.8 Syntax and semantics of modal predicates

- •6.3 Tense

- •6.3.1 Predicates and times, in general

- •6.3.2 Tense in finite adjectival and adverbial clauses

- •6.3.3 Tense in argument clauses

- •6.3.4 Shifts of perspective in tense: historical present

- •6.3.5 Shifts of perspective in tense: resultative

- •6.3.6 Tense in participles

- •6.3.7 Aspectual-temporal-modal particles

- •6.4 Aspect and lexicon

- •6.4.1 Aspect made simple

- •6.4.2 Tests for aspect membership

- •6.4.3 Aspect and morphology: the core strategy

- •6.4.4 Aspect and morphology: other strategies and groups

- •6.4.5 Aspect pairs

- •6.4.6 Intrinsic lexical aspect

- •6.4.7 Verbs of motion

- •6.5 Aspect and context

- •6.5.1 Preliminaries

- •6.5.2 Past ‘‘aoristic” narrative: perfective

- •6.5.3 Retrospective (‘‘perfect”) contexts: perfective and imperfective

- •6.5.4 The essentialist context: imperfective

- •6.5.5 Progressive context: imperfective

- •6.5.6 Durative context: imperfective

- •6.5.7 Iterative context: imperfective

- •6.5.8 The future context: perfective and imperfective

- •6.5.9 Exemplary potential context: perfective

- •6.5.10 Infinitive contexts: perfective and imperfective

- •6.5.11 Retrospective on aspect

- •6.6 Temporal adverbs

- •6.6.1 Temporal adverbs

- •6.6.2 Measured intervals

- •6.6.3 Time units

- •6.6.4 Time units: variations on the basic patterns

- •6.6.14 Frequency

- •6.6.15 Some lexical adverbs

- •6.6.16 Conjunctions

- •6.6.17 Summary

- •7 The presentation of information

- •7.1 Basics

- •7.2 Intonation

- •7.2.1 Basics

- •7.2.2 Intonation contours

- •7.3 Word order

- •7.3.1 General

- •7.3.6 Word order without subjects

- •7.3.7 Summary of word-order patterns of predicates and arguments

- •7.3.8 Emphatic stress and word order

- •7.3.9 Word order within argument phrases

- •7.3.10 Word order in speech

- •7.4 Negation

- •7.4.1 Preliminaries

- •7.4.2 Distribution and scope of negation

- •7.4.3 Negation and other phenomena

- •7.5 Questions

- •7.5.1 Preliminaries

- •7.5.2 Content questions

- •7.5.3 Polarity questions and answers

- •7.6 Lexical information operators

- •7.6.1 Conjunctions

- •7.6.2 Contrastive conjunctions

- •Bibliography

- •Index

10 A Reference Grammar of Russian

1.2.6 Two fundamental concepts of (Russian) grammar

While each construction, each problem of grammar, requires its own description, some general, recurrent ideas emerged. Two can be mentioned.

One is modality and the related concept of quantification. Every statement is understood against alternatives. Sometimes there is just a contrast of the mere fact that some x having one salient property exists at all, in contrast to the possibility that x might not hold, or that a certain situation holds in contrast to the possibility that might not exist (existential or essential quantification). Sometimes a specific individual x or property is contrasted with other possible x’s or ’s (individuated quantification). Modality -- consideration of alternatives by an authority -- pervades grammar.

The other is directionality, dialogicity. An utterance does not exist or have meaning in isolation, but is manipulated by speakers and addressees in a threestep process. The speaker invites the addressee to construct a background of information, taken as given and known (first step). Against this background the speaker formulates, and the addressee evaluates, the current assertion (second step). On the basis of that comparison, the speaker and addressee then project further conclusions or anticipate further events (third step). Thus the speaker invites the addressee to engage in a directional process of manipulating information.

These concepts -- modality (and quantification) and directionality -- pervade the grammar of Russian and, no doubt, other languages.

1.3 Writing Russian

1.3.1 The Russian Cyrillic alphabet

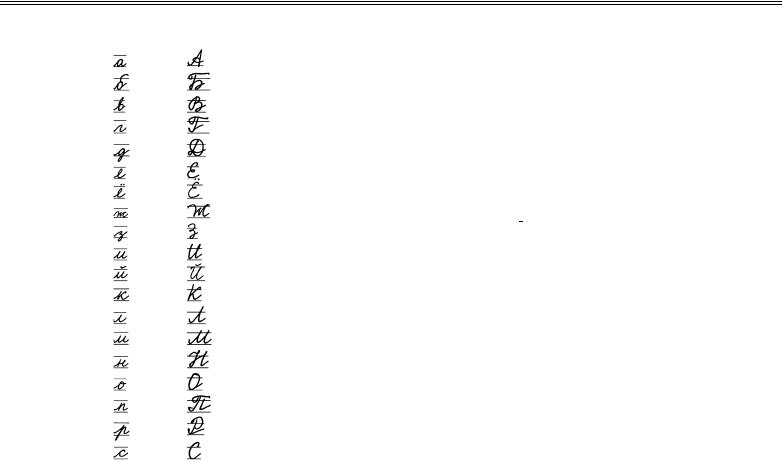

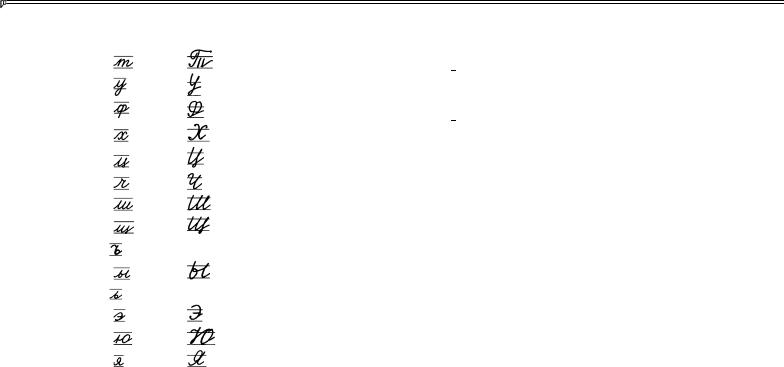

Russian is written not in the Latin letters used for English and Western European languages but in an alphabet called Cyrillic (Russian rbhbkkbwf). Cyrillic, with small differences, is also used for other languages -- Ukrainian, Serbian, Bulgarian. Cyrillic will be used to write Russian throughout the discussion below, with certain obvious exceptions: in the discussion of sounds and the internal structure of words, in glosses of Russian words or phrases, and in citations of scholarly literature. For reference, the version of the Cyrillic alphabet used for modern Russian is given in Table 1.3. In Column 1 the alphabet is presented in the lowerand uppercase forms used in printing. Column 2 gives the italic variants. Column 3 gives longhand forms of lowercase and then uppercase letters as used in connected, cursive writing (unusual uppercase letters are omitted); the subsequent discussion, however, will not treat handwriting.9 The contemporary

9 With thanks to Victoria Somoff for the handwriting sample.

Russian 11

name of the letter is given in Column 4. These names are mostly transparent. The names of consonant letters have a vowel added to the sound of the consonant. Four unusual letters are referred to by descriptive phrases. For reference, Column 5 gives the older names of the letters. Column 6 states approximate sound values of individual Cyrillic letters in English, although there are obvious difficulties in attempting to state the sound of Cyrillic letters in terms of English sounds: the closest English sound is not always particularly close; individual Cyrillic letters do not represent just a single sound (consonants can be palatalized or not; vowel letters have different value depending on whether or not they follow consonant letters). The statements of sound value are quite approximate.

Because Cyrillic is an alphabet, by establishing correspondences between each individual Cyrillic letter and one or more Latin letters, it is possible to rewrite, or transliterate, Cyrillic into Latin letters. Column 7 is the table of equivalences established by the Library of Congress as used in slightly simplified form in this study. (Other systems are discussed later: §1.3.7.) The final column gives sources of the Cyrillic letters. The alphabet given in Table 1.3 is the contemporary alphabet. The civil alphabet used until the reform of the October Revolution included two additional letters: ≤î≥ “b ltcznthbxyjt” (alphabetized between ≤b≥ and ≤r≥) and ≤˜≥ “znm” (between ≤m≥ and ≤э≥). Additional letters are found in Russian Church Slavic.10

From various people, one often hears that Russian must be a difficult language because its alphabet is so difficult. Nothing could be further from the truth. Whatever the difficulties of Russian, they cannot be blamed on the alphabet, which anyone with a modicum of ability in language systems and a vague acquaintance with the Greek alphabet can learn in half an hour, as will be demonstrated after a brief introduction to the history of the alphabet.

1.3.2 A brief history of the Cyrillic alphabet

The beginning of writing in Slavic is a fascinating tale that deserves to be told in brief.11 The story can be picked up at the end of the eighth century, around 796, when tribes of Slavs from the region of Moravia (in the south of the contemporary Czech Republic, along the Morava River) helped Charlemagne rid Central Europe of the last remnants of the Avars, a confederation of Eastern marauders. This venture marked the beginning of more active relations between Moravian Slavs and the West, both with secular political authorities (Charlemagne until his death in 917, his descendants thereafter) and with ecclesiastical

10 Library of Congress Romanization: ≤î≥ > ≤¯ı≥, ≤˜≥ > ≤ıe≥. Russian Church Slavic used also ≤º≥ >

ˇ

˙

≤f≥, ≤v≥ > ≤˙y≥

11 Dvornik 1970, Vlasto 1970.

Table 1.3 The Russian Cyrillic alphabet

Cyrillic |

Cyrillic |

Cyrillic |

contemporary |

archaic letter |

English equivalent |

Library of Congress |

etymology |

||||||||||||

(print) |

(italic) |

(longhand) |

letter name |

name |

(very approximate) |

Romanization |

of letter |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

f/F |

f/F |

|

f |

fp |

Masha | |

all |

a |

Gk A |

|||||||||||

,/< |

,/< |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

,э |

,erb |

bother |

|

|

|

b |

Gk B |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

d/D |

d/D |

|

dэ |

dtlb |

Volga |

|

|

|

v |

Gk B |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

u/U |

u/U |

|

uэ |

ukfujk |

guard |

|

|

|

g |

Gk |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

l/L |

l/L |

|

lэ |

lj,hj |

do |

|

|

|

d |

Gk |

|||||||||

t/T |

t/T |

|

t [åt] |

tcnm |

|

|

|

|

Pierre | yell |

e |

Gk E |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

=/+ |

=/+ |

|

= [åj] |

-- |

Fyodor | |

yoyo |

e |

Cyr t/T |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

;/: |

;/: |

|

;э |

;bdbnt |

azure, French je |

zh |

Gl æ |

||||||||||||

p/P |

p/P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

pэ |

ptvkz |

zoo |

|

|

|

z |

Gk Z |

|||||||||||

b/B |

b/B |

|

b |

b |

|

|

beat | eat |

i |

Gk H |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

q/æ |

q/Q |

|

b rhfnrjt |

-- |

boy |

|

|

|

i |

Cyr b/B |

|||||||||

r/R |

r/R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

rf |

rfrj |

car |

|

|

|

k |

Gk K |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

k/K |

k/K |

|

эkm |

k/lb |

Leeds |

|

|

|

l |

Gk |

|||||||||

v/V |

v/V |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

эv |

vsckbnt |

Masha |

|

|

|

m |

Gk M |

|||||||||||

y/Y |

y/Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

эy |

yfi |

no |

|

|

|

n |

Gk N |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

j/J |

j/J |

|

j |

jy |

go | only |

|

|

|

o |

Gk O |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

g/G |

g/G |

|

gэ |

gjrjq |

pot |

|

|

|

p |

Gk |

|||||||||

h/H |

h/H |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

эh |

hws |

rot |

|

|

|

r |

Gk P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

c/C |

c/C |

|

эc |

ckjdj |

sew |

|

|

|

s |

Gk |

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1.3 (cont.)

Cyrillic |

Cyrillic |

Cyrillic |

contemporary |

archaic letter |

English equivalent |

Library of Congress |

etymology |

||||||||||||

(print) |

(italic) |

(longhand) |

letter name |

name |

(very approximate) |

Romanization |

of letter |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

n/N |

n/N |

|

nэ |

ndthlj |

toe |

t |

Gk T |

||||||||||||

e/E |

e/E |

|

e |

er |

do | oops |

u |

Gk Y |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a/A |

a/A |

|

эa |

athn |

far |

f |

Gk |

||||||||||||

[/{ |

[/{ |

|

[f |

[th |

German ach |

kh |

Gk { |

||||||||||||

w/W |

w/W |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

wэ |

ws |

tsetse, prints |

ts |

Gl Ö |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gl ÷ |

x/X |

x/X |

|

xt |

xthdm |

church |

ch |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gl Ø |

|

i/I |

i/I |

|

if |

if |

shallow, fish |

sh |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

o/O |

o/O |

|

of |

inf |

Josh should, fish shop |

shch |

Gl ù |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

ndthlsq pyfr (th∞ ) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

( |

( |

|

th |

[boundary marker] |

Gl ú |

||||||||||||||

s/S |

s/S |

|

s, ths∞ |

ths |

pituitary |

y |

Gl û |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

vzurbq pyfr (thm∞ ) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

m |

m |

|

thm |

[consonant palatalized] |

Gl ü |

||||||||||||||

э/э |

э/э |

|

э j,jhjnyjt |

-- |

best | Evan |

e |

Cyr t/T |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

//? |

//? |

|

/ |

/ |

cute | yule |

iu |

Gl |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yalta |

|

Cyr b |

|||||||

z/Z |

z/Z |

|

z |

z |

|

Diaghilev |

ia |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

x | y = pronunciation after consonant letter | pronunciation not after consonant letter Gk = Greek

Gl = Glagolitic

Cyr = (earlier) Cyrillic

x∞ = older name still used (SRIa 1.152)

14A Reference Grammar of Russian

authorities. As part of this interaction, missionaries were sent to the Moravians from the Franks (from the relatively new bishoprics of Regensburg, Passau, Salzburg) and from the Italians (from the bishopric of Aquileia). The conversion of Prince Mojmír of Moravia (r. 818--46) in 822 was followed by a general baptism in 831. In this period of missionary activity, churches -- some in stone -- were constructed at sites in Moravia such as Mikulˇcice.

In 846, Mojmír’s nephew Rostislav took control and began to act with greater autonomy. After the bishopric of Salzburg had its charter renewed in 860, Rostislav took steps to avoid further ecclesiastical interference from the Franks. In 862, after having been put off by the Pope, he approached the Byzantine Emperor Michael III with a famous request:

Though our people have rejected paganism and observe Christian law, we have not a teacher who would explain to us in our language the true Christian faith, so that other countries which look to us might emulate us. Therefore, O lord, send us such

a bishop and teacher. (Kantor and White 1976:45)

Emperor Michael and Patriarch Photius responded by sending Constantine (canonized as St. Cyril) and Methodius, two brothers educated in Greek who spoke a Slavic language, to Moravia to train disciples and translate the liturgy and the Bible into Slavic. In order to write in Slavic, they devised an alphabet which is now called Glagolitic. The letters of Glagolitic are stylized combinations of strokes and loops; for example, the chapter title for Luke 11 (Marianus) reads in Glagolitic,

‘on the catching of fish’).12 It is still an open question what sources Constantine and Methodius used for this new alphabet. It has long been assumed that the model was Greek minuscule,13 but it may have been cursive of a Latin (specifically Carolingian) type.14 Whatever the source of the alphabet, writing in Slavic has its origins in the “Moravian mission” of Constantine (St. Cyril) and Methodius.

‘on the catching of fish’).12 It is still an open question what sources Constantine and Methodius used for this new alphabet. It has long been assumed that the model was Greek minuscule,13 but it may have been cursive of a Latin (specifically Carolingian) type.14 Whatever the source of the alphabet, writing in Slavic has its origins in the “Moravian mission” of Constantine (St. Cyril) and Methodius.

The Moravian mission began auspiciously. It was given papal approval when the brothers traveled with their disciples to Rome (867). After Constantine died in Rome (869), Methodius was appointed bishop of a large missionary area including Moravia and Pannonia. In the long run, however, the mission proved vulnerable. It was resented by the Frankish bishops, who went so far as to imprison

12Jagi´c 1883 (interleaf 110--11, 186).

13Beginning with Taylor (1880, 1883), who exhibited apparent similarities between individual Glagolitic letters and Greek minuscule letters.

14Lettenbauer 1953 (summarizing an inaccessible study, Hocij 1940) cites intriguing pairs of Glagolitic and Carolingian letters. For example, the Carolingian ≤j≥ is a vertical arc open on the left, with loops both on the top and at the bottom, hence very similar to the double loop of Glagolitic ≤î≥; Taylor’s Greek cursive omicron has no loops. Taylor’s Greek cursive ≤l≥ looks like a modern English cursive ≤l≥, with an internal loop (that is, ≤ ≥), very unlike the Glagolitic double-looped ≤ä≥, which looks like the Carolingian.

Russian 15

Methodius until the Pope secured his release. Rostislav, the Moravian prince who originally sponsored the mission, was blinded and exiled. When Methodius died in 885, a hostile bishop (Wiching of Nitra) chased out the troublemakers and reinstalled the Latin rite. Disciples of Constantine and Methodius were fortunate to make it to Ohrid and Bulgaria.

In Bulgaria, Tsar Boris, who had initially converted to Christianity in 863, held a council in Preslav in 893, at which he abdicated, turned over power to his pro-Christian son Symeon, and appointed Clement, one of the original Moravian disciples, as bishop. Around this time, conceivably at this council,15 the practice was established of writing religious texts in Slavic in letters that were modeled to the extent possible on Greek majuscule letters.16 (For Slavic sounds that had no equivalents in Greek, letters were adapted from Glagolitic.) This neophyte Christian culture, with sacred texts written in Slavic in this Greeklike alphabet, flourished in Bulgaria in the first half of the tenth century, until the time (in 971) when Byzantium defeated Boris II and absorbed the Bulgarian patriarchate. This tradition of writing was brought to Rus as a consequence of the conversion to Christianity in 988. The alphabet that was imported was the direct ancestor of the alphabet in which modern Russian is written, the alphabet we call “Cyrillic.” As this brief sketch shows, Cyril himself did not invent the Cyrillic alphabet. But he and his brother did invent the alphabet in which Slavic was written systematically for the first time, and the alphabet they constructed did provide the model for Cyrillic.

After having been brought into East Slavic territory, this alphabet was used in the oldest principalities of Kiev, Novgorod, and Vladimir-Rostov-Suzdal from the eleventh century on, and then subsequently in Moscow, the principality that emerged as dominant as the “Mongol yoke” was loosened. This alphabet has continued to be used with only modest changes until the present day. Peter the Great attempted to reform the orthography in 1708--10. His new civil alphabet (uhf;lfyrf) had letters of a cleaner, less ornate (more Western) shape. Peter also proposed that, in instances where more than one letter had the same sound value, only one letter be preserved, the first of the sets

for the sound [i],

for the sound [i],  for [z],

for [z],  for [o], ≤y/U≥ for [u], ≤a/f≥ for [f]; some other letters with quite specific functions

for [o], ≤y/U≥ for [u], ≤a/f≥ for [f]; some other letters with quite specific functions  were also to be eliminated.17 Although all of Peter’s proposals did not catch on, his initiatives led to modernizing the graphic shape of the alphabet and set in motion the process of rationalizing the inventory of letters. While the general trend has been to simplify the

were also to be eliminated.17 Although all of Peter’s proposals did not catch on, his initiatives led to modernizing the graphic shape of the alphabet and set in motion the process of rationalizing the inventory of letters. While the general trend has been to simplify the

15Dvornik 1970:250--52; Vlasto 1970:168--76.

16The similarity is quite striking between early Cyrillic writing and contemporary Greek Gospels, for example Lord Zouche’s gospel text from 980 (Plate IV, Gardtgauzen 1911).

17Zhivov 1996:73--77.