- •Preface

- •List of contributers

- •History, epidemiology, prevention and education

- •A history of burn care

- •“Black sheep in surgical wards”

- •Toxaemia, plasmarrhea, or infection?

- •The Guinea Pig Club

- •Burns and sulfa drugs at Pearl Harbor

- •Burn center concept

- •Shock and resuscitation

- •Wound care and infection

- •Burn surgery

- •Inhalation injury and pulmonary care

- •Nutrition and the “Universal Trauma Model”

- •Rehabilitation

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Epidemiology and prevention of burns throughout the world

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •The inequitable distribution of burns

- •Cost by age

- •Cost by mechanism

- •Limitations of data

- •Risk factors

- •Socioeconomic factors

- •Race and ethnicity

- •Age-related factors: children

- •Age-related factors: the elderly

- •Regional factors

- •Gender-related factors

- •Intent

- •Comorbidity

- •Agents

- •Non-electric domestic appliances

- •War, mass casualties, and terrorism

- •Interventions

- •Smoke detectors

- •Residential sprinklers

- •Hot water temperature regulation

- •Lamps and stoves

- •Fireworks legislation

- •Fire-safe cigarettes

- •Children’s sleepwear

- •Acid assaults

- •Burn care systems

- •Role of the World Health Organization

- •Conclusions and recommendations

- •Surveillance

- •Smoke alarms

- •Gender inequality

- •Community surveys

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Prevention of burn injuries

- •Introduction

- •Burns prevalence and relevance

- •Burn injury risk factors

- •WHERE?

- •Burn prevention types

- •Burn prevention: The basics to design a plan

- •Flame burns

- •Prevention of scald burns

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Burns associated with wars and disasters

- •Introduction

- •Wartime burns

- •Epidemiology of burns sustained during combat operations

- •Fluid resuscitation and initial burn care in theater

- •Evacuation of thermally-injured combat casualties

- •Care of host-nation burn patients

- •Disaster-related burns

- •Epidemiology

- •Treatment of disaster-related burns

- •The American Burn Association (ABA) disaster management plan

- •Summary

- •References

- •Education in burns

- •Introduction

- •Surgical education

- •Background

- •Simulation

- •Education in the internet era

- •Rotations as courses

- •Mentorship

- •Peer mentorship

- •Hierarchical mentorship

- •What is a mentor

- •Implementation

- •Interprofessional education

- •What is interprofessional education

- •Approaches to interprofessional education

- •References

- •European practice guidelines for burn care: Minimum level of burn care provision in Europe

- •Foreword

- •Background

- •Introduction

- •Burn injury and burn care in general

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Pre-hospital and initial management of burns

- •Introduction

- •Modern care

- •Early management

- •At the accident

- •At a local hospital – stabilization prior to transport to the Burn Center

- •Transportation

- •References

- •Medical documentation of burn injuries

- •Introduction

- •Medical documentation of burn injuries

- •Contents of an up-to-date burns registry

- •Shortcomings in existing documentation systems designs

- •Burn depth

- •Burn depth as a dynamic process

- •Non-clinical methods to classify burn depth

- •Burn extent

- •Basic principles of determining the burn extent

- •Methods to determine burn extent

- •Computer aided three-dimensional documentation systems

- •Methods used by BurnCase 3D

- •Creating a comparable international database

- •Results

- •Conclusion

- •Financing and accomplishment

- •References

- •Pathophysiology of burn injury

- •Introduction

- •Local changes

- •Burn depth

- •Burn size

- •Systemic changes

- •Hypovolemia and rapid edema formation

- •Altered cellular membranes and cellular edema

- •Mediators of burn injury

- •Hemodynamic consequences of acute burns

- •Hypermetabolic response to burn injury

- •Glucose metabolism

- •Myocardial dysfunction

- •Effects on the renal system

- •Effects on the gastrointestinal system

- •Effects on the immune system

- •Summary and conclusion

- •References

- •Anesthesia for patients with acute burn injuries

- •Introduction

- •Preoperative evaluation

- •Monitors

- •Pharmacology

- •Postoperative care

- •References

- •Diagnosis and management of inhalation injury

- •Introduction

- •Effects of inhaled gases

- •Carbon monoxide

- •Cyanide toxicity

- •Upper airway injury

- •Lower airway injury

- •Diagnosis

- •Resuscitation after inhalation injury

- •Other treatment issues

- •Prognosis

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Respiratory management

- •Airway management

- •(a) Endotracheal intubation

- •(b) Elective tracheostomy

- •Chest escharotomy

- •Conventional mechanical ventilation

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiological principles

- •Low tidal volume and limited plateau pressure approaches

- •Permissive hypercapnia

- •The open-lung approach

- •PEEP

- •Lung recruitment maneuvers

- •Unconventional mechanical ventilation strategies

- •High-frequency percussive ventilation (HFPV)

- •High-frequency oscillatory ventilation

- •Airway pressure release ventilation (APRV)

- •Ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP)

- •(a) Prevention

- •(b) Treatment

- •References

- •Organ responses and organ support

- •Introduction

- •Burn shock and resuscitation

- •Post-burn hypermetabolism

- •Individual organ systems

- •Central nervous system

- •Peripheral nervous system

- •Pulmonary

- •Cardiovascular

- •Renal

- •Gastrointestinal tract

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Critical care of thermally injured patient

- •Introduction

- •Oxidative stress control strategies

- •Fluid and cardiovascular management beyond 24 hours

- •Other organ function/dysfunction and support

- •The nervous system

- •Respiratory system and inhalation injury

- •Renal failure and renal replacement therapy

- •Gastro-intestinal system

- •Glucose control

- •Endocrine changes

- •Stress response (Fig. 2)

- •Low T3 syndrome

- •Gonadal depression

- •Thermal regulation

- •Metabolic modulation

- •Propranolol

- •Oxandrolone

- •Recombinant human growth hormone

- •Insulin

- •Electrolyte disorders

- •Sodium

- •Chloride

- •Calcium, phosphate and magnesium

- •Calcium

- •Bone demineralization and osteoporosis

- •Micronutrients and antioxidants

- •Thrombosis prophylaxis

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Treatment of infection in burns

- •Introduction

- •Clinical management strategies

- •Pathophysiology of the burn wound

- •Burn wound infection

- •Cellulitis

- •Impetigo

- •Catheter related infections

- •Urinary tract infection

- •Tracheobronchitis

- •Pneumonia

- •Sepsis in the burn patient

- •The microbiology of burn wound infection

- •Sources of organisms

- •Gram-positive organisms

- •Gram-negative organisms

- •Infection control

- •Pharmacological considerations in the treatment of burn infections

- •Topical antimicrobial treatment

- •Systemic antimicrobial treatment (Table 3)

- •Gram-positive bacterial infections

- •Enterococcal bacterial infections

- •Gram-negative bacterial infections

- •Treatment of yeast and fungal infections

- •The Polyenes (Amphotericin B)

- •Azole antifungals

- •Echinocandin antifungals

- •Nucleoside analog antifungal (Flucytosine)

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Acute treatment of severely burned pediatric patients

- •Introduction

- •Initial management of the burned child

- •Fluid resuscitation

- •Sepsis

- •Inhalation injury

- •Burn wound excision

- •Burn wound coverage

- •Metabolic response and nutritional support

- •Modulation of the hormonal and endocrine response

- •Recombinant human growth hormone

- •Insulin-like growth factor

- •Oxandrolone

- •Propranolol

- •Glucose control

- •Insulin

- •Metformin

- •Novel therapeutic options

- •Long-term responses

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Adult burn management

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology and aetiology

- •Pathophysiology

- •Assessment of the burn wound

- •Depth of burn

- •Size of the burn

- •Initial management of the burn wound

- •First aid

- •Burn blisters

- •Escharotomy

- •General care of the adult burn patient

- •Biological/Semi biological dressings

- •Topical antimicrobials

- •Biological dressings

- •Other dressings

- •Exposure

- •Deep partial thickness wound

- •Total wound excision

- •Serial wound excision and conservative management

- •Full thickness burns

- •Excision and autografting

- •Topical antimicrobials

- •Large full thickness burns

- •Serial excision

- •Mixed depth burn

- •Donor sites

- •Techniques of wound excision

- •Blood loss

- •Antibiotics

- •Anatomical considerations

- •Skin replacement

- •Autograft

- •Allograft

- •Other skin replacements

- •Cultured skin substitutes

- •Skin graft take

- •Rehabilitation and outcome

- •Future care

- •References

- •Burns in older adults

- •Introduction

- •Burn injury epidemiology

- •Pathophysiologic changes and implications for burn therapy

- •Aging

- •Comorbidities

- •Acute management challenges

- •Fluid resuscitation

- •Burn excision

- •Pain and sedation

- •End of life decisions

- •Summary of key points and recommendations

- •References

- •Acute management of facial burns

- •Introduction

- •Anatomy and pathophysiology

- •Management

- •General approach

- •Airway management

- •Facial burn wound management

- •Initial wound care

- •Topical agents

- •Biological dressings

- •Surgical burn wound excision of the face

- •Wound closure

- •Special areas and adjacent of the face

- •Eyelids

- •Nose and ears

- •Lips

- •Scalp

- •The neck

- •Catastrophic injury

- •Post healing rehabilitation and scar management

- •Outcome and reconstruction

- •Summary

- •References

- •Hand burns

- •Introduction

- •Initial evaluation and history

- •Initial wound management

- •Escharotomy and fasciotomy

- •Surgical management: Early excision and grafting

- •Skin substitutes

- •Amputation

- •Hand therapy

- •Secondary reconstruction

- •References

- •Treatment of burns – established and novel technology

- •Introduction

- •Partial thickness burns

- •Biological membranes – amnion and others

- •Xenograft

- •Full thickness burns

- •Dermal analogs

- •Keratinocyte coverage

- •Facial transplantation

- •Tissue engineering and stem cells

- •Gene therapy and growth factors

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Wound healing

- •History of wound care

- •Types of wounds

- •Mechanisms of wound healing

- •Hemostasis

- •Proliferation

- •Epithelialization

- •Remodeling

- •Fetal wound healing

- •Stem cells

- •Abnormal wound healing

- •Impaired wound healing

- •Hypertrophic scars and keloids

- •Chronic non-healing wounds

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Pain management after burn trauma

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology of pain after burn injuries

- •Nociceptive pain

- •Neuropathic pain

- •Sympathetically Maintained Pain (SMP)

- •Pain rating and documentation

- •Pain management and analgesics

- •Pharmacokinetics in severe burns

- •Form of administration [21]

- •Non-opioids (Table 1)

- •Paracetamol

- •Metamizole

- •Non-steroidal antirheumatics (NSAID)

- •Selective cyclooxygenasis-2-inhibitors

- •Opioids (Table 2)

- •Weak opioids

- •Strong opioids

- •Other analgesics

- •Ketamine (see also intensive care unit and analgosedation)

- •Anticonvulsants (Gabapentin and Pregabalin)

- •Antidepressants with analgesic effects

- •Regional anesthesia

- •Pain management without analgesics

- •Adequate communication

- •Psychological techniques [65]

- •Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- •Particularities of burn pain

- •Wound pain

- •Breakthrough pain

- •Intervention-induced pain

- •Necrosectomy and skin grafting

- •Dressing change of large burn wounds and removal of clamps in skin grafts

- •Dressing change in smaller burn wounds, baths and physical therapy

- •Postoperative pain

- •Mental aspects

- •Intensive care unit

- •Opioid-induced hyperalgesia and opioid tolerance

- •Hypermetabolism

- •Psychic stress factors

- •Risk of infection

- •Monitoring [92]

- •Sedation monitoring

- •Analgesia monitoring (see Fig. 2)

- •Analgosedation (Table 3)

- •Sedation

- •Analgesia

- •References

- •Nutrition support for the burn patient

- •Background

- •Case presentation

- •Patient selection: Timing and route of nutritional support

- •Determining nutritional demands

- •What is an appropriate initial nutrition plan for this patient?

- •Formulations for nutritional support

- •Monitoring nutrition support

- •Optimal monitoring of nutritional status

- •Problems and complications of nutritional support

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •HBO and burns

- •Historical development

- •Contraindications for the use of HBO

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Nursing management of the burn-injured person

- •Introduction

- •Incidence

- •Prevention

- •Pathophysiology

- •Severity factors

- •Local damage

- •Fluid and electrolyte shifts

- •Cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal system manifestations

- •Types of burn injuries

- •Thermal

- •Chemical

- •Electrical

- •Smoke and inhalation injury

- •Clinical manifestations

- •Subjective symptoms

- •Possible complications

- •Clinical management

- •Non-surgical care

- •Surgical care

- •Coordination of care: Burn nursing’s unique role

- •Nursing interventions: Emergent phase

- •Nursing interventions: Acute phase

- •Nursing interventions: Rehabilitative phase

- •Ongoing care

- •Infection prevention and control

- •Rehabilitation medicine

- •Nutrition

- •Pharmacology

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Outpatient burn care

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Accident causes

- •Care structures

- •Indications for inpatient treatment

- •Patient age

- •Total burned body surface area (TBSA)

- •Depth of the burn

- •Pre-existing conditions

- •Accompanying injuries

- •Special injuries

- •Treatment

- •Initial treatment

- •Pain therapy

- •Local treatment

- •Course of treatment

- •Complications

- •Infections

- •Follow-up care

- •References

- •Non-thermal burns

- •Electrical injury

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology

- •Initial assessment and acute care

- •Wound care

- •Diagnosis

- •Low voltage injuries

- •Lightning injuries

- •Complications

- •References

- •Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of chemical burns

- •Chemical burns

- •Decontamination

- •Affection of different organ systems

- •Respiratory tract

- •Gastrointestinal tract

- •Hematological signs

- •Nephrologic symptoms

- •Skin

- •Nitric acid

- •Sulfuric acid

- •Caustic soda

- •Phenol

- •Summary

- •References

- •Necrotizing and exfoliative diseases of the skin

- •Introduction

- •Necrotizing diseases of the skin

- •Cellulitis

- •Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- •Autoimmune blistering diseases

- •Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

- •Necrotizing fasciitis

- •Purpura fulminans

- •Exfoliative diseases of the skin

- •Stevens-Johnson syndrome

- •Toxic epidermal necrolysis

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Frostbite

- •Mechanism

- •Risk factors

- •Causes

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Rewarming

- •Surgery

- •Sympathectomy

- •Vasodilators

- •Escharotomy and fasciotomy

- •Prognosis

- •Research

- •References

- •Subject index

Pain management after burn trauma

en from the wound during the numerous therapeutical measures and thus limit their efficacy.

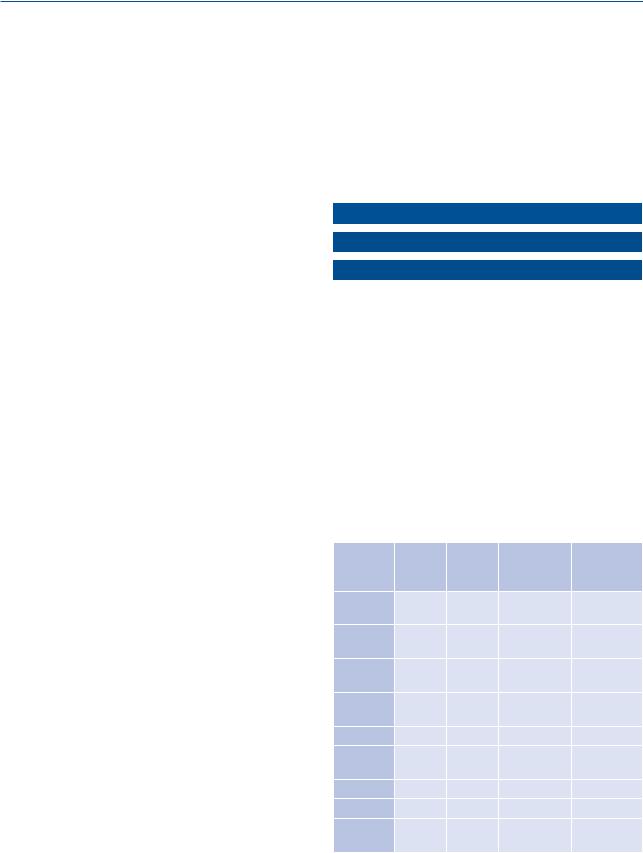

Modified WHO pain ladder (see Fig. 1)

Depending on pain intensity and pain history the application of the (modified) WHO pain ladder can be recommended: Therapy starts either on stage 1 and is increased until sufficient analgetics are administered or already begins on a higher stage, which is often necessary in burn injuries.

Non-opioids (Table 1)

It is recommended to apply basic treatment with non-opioids. Side effects and possible complications as mentioned below should always be considered.

Non-opioids reduce the opioid requirement by 20% to 30% [22]. NSAID can reduce the side effects caused by opioids significantly [23]. By blocking the cyclooxygenasis or blocking the development of PG E2, a stimulation of the NMDA-receptor-NO system with development of an opioid tolerance and opioidinduced hyperalgesia can be reduced [24, 25].

Step I |

Step II |

Step III |

|

|

|

|

|

Strong opioids |

|

Weak/Moderate |

Morphine |

|

opioids |

Hydromorphone |

|

Tramadol |

Fentanyl |

Non-opiod |

Pethidine |

Oxycodon |

analgesics |

|

Methadon |

NSAID, Coxibe |

|

|

Metamizole |

|

|

Paracetamol |

+ Step 1 |

+Step 1 |

|

|

|

Ketamin, anticonvulsants, antidepressants

Treatment without medication

Regional anesthetic

Fig. 1. Modified WHO pain ladder

Paracetamol should be administered carefully if the patient suffers from chronic alcoholism or chronic malnutrition as in these cases the reserves of hepatic glutathione are low. Paracetamol can be administered enterally, parenterally or rectally. The benefits of an intravenous administration is a rapid invasion of the active ingredients into the central nervous system. Compared to an oral administration, an intra-

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is part of the non-acidic antipyretic analgesics. The exact mechanism of the analgentic and antipyretic effects has not been fully investigated yet. However, central and peripheral points of action might play a role in the efficacy of paracetamol. Influences to the serotonergic system have already been verified [26].

The maximum daily dose for adults of normal weight is 4 000 mg, maximum dose for children is 60 mg/kgBW. Daily doses of paracetamol above 100 mg/kgBW (6g to 8g daily) are hepatoxic. It has to be considered though that the administration of the normal daily dose can also cause liver cell necrosis and liver failure in case of pre-existing liver disorders and/or glutathione deficiency. N-acetycysteine is an efficient antidote and should be administered within 10 hours after the overdosage if possible.

A contra-indication for administering paracetamol is the presence of severe liver insufficiency.

Table 1. Pharmacological data of non-opioids

Active |

HL (h) |

Ad- |

Single dose |

Daily |

Ingred- |

|

minis- |

in adults |

maximum |

ient |

|

tration |

(mg) |

dose (mg) |

Diclo- |

|

p. o., |

|

|

fenac |

1–2 |

i. v. |

50–75 |

150 |

Ibu- |

|

|

|

|

profen |

1,5–2,5 |

p. o. |

200–800 |

2400 |

Lorn- |

|

p. o., |

|

|

oxicam |

3–4 |

i. v. |

8 |

16 |

Paraceta- |

|

|

|

|

mol |

1,5–2,5 |

p. o. |

500–1000 |

4000 |

|

|

i. v. |

1000 |

4000 |

Metami- |

|

|

|

|

zole |

2–4 |

p. o. |

500–1000 |

4000 |

|

|

i. v. |

1000–2500 |

5000 |

Celecoxib |

11 |

p. o. |

100–200 |

400 |

Pare- |

|

|

|

|

coxib |

~ 22 |

i. v. |

40 |

80 |

343

R. Girtler, B. Gustorff

venous administration takes effect faster and more effectively [27]. The analgesic effect of paracetamol administered intravenously occurs within 5 to 10 minutes and generally persists for 4 to 6 hours.

Among all non-opioids only paracetamol can be administered safely during pregnancy and lactation period.

Metamizole

Metamizole belongs to the non-acidic antipyretic analgesics. It is one of the most efficient non-opioids and additionally has a spasmolytic effect.

The exact mechanism of metamizole is still unknown. Basically it is assumed that it has a central effect. An additional peripheral analgesic effect by inhibiting the prostaglandinesynthesis is described for pyrazolonederivates [28].

Metamizole does not combine in acidic tissue, does not have any pharmacologically active metabolites and is mostly egested renally. Compared to NSAID, the benefit of metamizole is few interaction with the thrombocyte function. Metamizole can be administered enterally, parenterally, intramuscularly, and rectally. Contrary to most of the NSAID, metamizole can be administered in any form to children of 3 months and older. A single dose for an adult is between 1g and 2.5g with a daily maximum dose of 5g. In children it is recommended to administer 10 mg/kg/BW to 25 mg/kgBW orally or rectally and 10 mg/kgBW to 15 mg/kgBW intravenously every 4 to 6 hours.

The risk of agranulocytosis is described controversially, with incidences of 1 : 1,000,000 [29] to 1 : 1,451 in Sweden [30]. The risk of an agranulocytosis during a permanent therapy with metamizole can be minimized by regular blood counts. A rapid infusion of metamizole can cause severe hypotonia due to anaphylactoid reactions.

Non-steroidal antirheumatics (NSAID)

NSAID have analgesic, antipyretic and antiphlogistic effects. They are nonselective inhibitors of the enzyme cyclooxygenasis, which plays a key role in the prostaglandine synthesis. They are bound with more than 90% to plasmaproteins and enrich in tissue that has been altered by inflammation.

The mechanism relevant for an analgesic therapy mightbetheriseintheexcitationthresholdofnociceptors after inhibition of the prostaglandine synthesis. The anatomic area of action of the substances has not been fully explained yet, however central and peripheral points of action have been described so far.

NSAID have numerous side-effects. When administered only for a short-time, renal disorders and disorders in the thrombocyte function are most commonly observed. The risk of post-surgical bleeding under therapy with non-opioids is discussed controversially. The bleeding time is increased by approximately 30% under the administration of NSAID. Thus, due to the inhibition of the thrombocyte aggregation, NSAID should only be administered when there is no more need for a bleeding intensive necrosectomy.

In a long-term administration, gastric, cardiac and renal effects are most commonly observed.

Diclofenac: Approved for short-term administration (max. 2 weeks). No recommendation for children younger than 14 years. However, the administration is very common in numerous countries due to lack of alternatives. Dosage: 50 mg to 150 mg daily in 2 or 3 single doses.

Lornoxicam: Not recommended for children and teenagers younger than 18 years. No special dosage instructions for older patients. Dosage: 8 mg to 16 mg daily in 2 or 3 single doses.

Ibuprofen: Ibuprofen does not have many sideeffects. It shows the lowest ulcerogenic potency of all NSAID. As syrup approved for children and infants from the age of 6 months.

Selective cyclooxygenasis-2-inhibitors

The discovery of at least 2 cyclooxygenasis-isoen- zymes has lead to the development of a cyclogen- asis-2 selective group of analgesics, which differs from the other NSAID particularly because of their missing thrombocyte function disorder and the significantly reduced gastro-intestinal side-effects.

However, numerous large-scale randomized studies showed a cardiovascular toxicity [31–33]. According to the recommendation of the European Medicines Agency, selective cyclooxygenase-2-in- hibitors are contra-indicated in the presence of clinically diagnosed coronary heart disorders, clinic-

344