clavien_atlas_of_upper_gastrointestinal_and_hepato-pancreato-biliary_surgery2007-10-01_3540200045_springer

.pdf

Necrosectomy

Waldemar Uhl, Oliver Strobel, Markus W. Buchler (Open Necrosectomy with Closed Postoperative Lavage),

Carlos Fernández-del Castillo (Necrosectomy and Closed Packing), Gregory G. Tsiotos, Michael G. Sarr (Planned Repeated Necrosectomy), C. Ross Carter, Clement W. Imrie (Percutaneous Necrosectomy)

Introduction

Severe acute pancreatitis remains a life-threatening disease. The first phase (about 10–14days) is characterized by formation of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis and development of a systemic inflammatory response syndrome. This systemic response to the pancreatic inflammation/necrosis causes early organ failure that necessitates intensive care therapy. In the second phase (after 2weeks), the leading cause of morbidity and mortality is superinfection of necrosis with development of septic multiple organ failure. In the last 2decades, treatment has evolved considerably, and with improved intensive care management, there is a worldwide trend toward a more conservative strategy with operative intervention initiated primarily because of the local and systemic manifestations of infected necrosis and less so for sterile necrosis. However, today, septic complications caused by pancreatic infection account for 80% of the mortality, and infected necrosis therefore usually remains an absolute indication for same form of invasive intervention.

The goals of operative necrosectomy are to remove the necrotic and infected tissue and to minimize injury to viable tissues. In addition, each technique described below also aims to minimize the accumulation of exudative fluid and extravasated pancreatic exocrine secretions from the operative bed, because if undrained, infection invariably occurs.

This section will discuss four operative techniques of necrosectomy and drainage. All have similarities in their ultimate goal of complete debridement of necrotic tissue, but all tend to achieve this goal differently. Indeed, individual patients may be best treated selectively.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications |

■ |

Pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis (based on contrast-enhanced dynamic CT |

|

|

scan) complicated by documented infection (guided FNA culture or extraluminal |

|

|

retroperitoneal gas). |

|

■ Sterile necrosis with progressive clinical deterioration despite maximal medical |

|

|

|

treatment; an aggressive operative approach in the absence of documented infection |

|

|

is, however, controversial. |

|

■ Timing: Necrosectomy should be undertaken as late as possible after onset of disease, |

|

|

|

when the necrotic process has ceased, viable and nonviable tissues are well demar- |

|

|

cated, and the infected necrotic tissues are better organized and “walled off.” |

|

■ |

Operative necrosectomy for patients greater than 3–4weeks after onset of disease |

|

|

who are not improving and cannot eat but who have documented “sterile necrosis” |

|

|

remains controversial – some groups maintain that recovery is speeded with |

|

|

necrosectomy; others maintain a nonoperative approach ultimately proves safer. |

|

■ |

Massive hemorrhage or bowel perforation (colon, duodenum). |

894 |

SECTION 6 |

Pancreas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis without evidence of infection or clinical |

|

Contraindications |

■ |

||

|

|

deterioration. |

|

|

■ |

Early operation (within 1week from onset of acute pancreatitis) before the systemic |

|

|

|

inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) has subsided and maximal intensive |

|

|

|

medical treatment is still necessary. Hemodynamic and metabolic instability early |

|

|

|

after necrotizing pancreatitis is secondary to SIRS and not to bacterial sepsis. |

|

Preoperative Investigation and Preparation for Procedure

■The diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is one of exclusion (exclude other surgical conditions) based on history, physical examination, and biochemistry.

■Initial assessment and continuous intensive care unit monitoring of severity (APACHE-II score).

■Laboratory assessment – CBC and electrolytes, liver function tests, and coagulation profile; some groups utilize serum C-reactive protein as a diagnostic/prognostic guide.

■Cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic resuscitation; aggressive management of SIRS for the first 10–14days of acute pancreatitis.

■Contrast-enhanced dynamic CT about 1week from onset of acute pancreatitis to assess the presence and extent of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic tissue necrosis, as well as extraluminal retroperitoneal gas.

■Early “prophylactic” administration of appropriate antibiotics (Imipenem) to prevent pancreatic superinfection from the gut is adopted by most, but not all, surgeons;

use of oral antifungal agents is favored.

■Initiation of parenteral nutrition with early conversion to intrajejunal feeding (using a nasojejunal tube with its tip distal to the fourth portion of the duodenum); if possible, intragastric feeding may be effective.

■In severe gallstone pancreatitis, if choledocholithiasis is present, early endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone removal decreases morbidity and mortality.

■When operation is planned, the preoperative CT serves as the “road map” for necrosectomy to delineate all fluid collections in areas remote from the pancreas, especially for the retroperitoneal paracolic gutters and perinephric spaces.

896 |

SECTION 6 |

Pancreas |

|

|

|

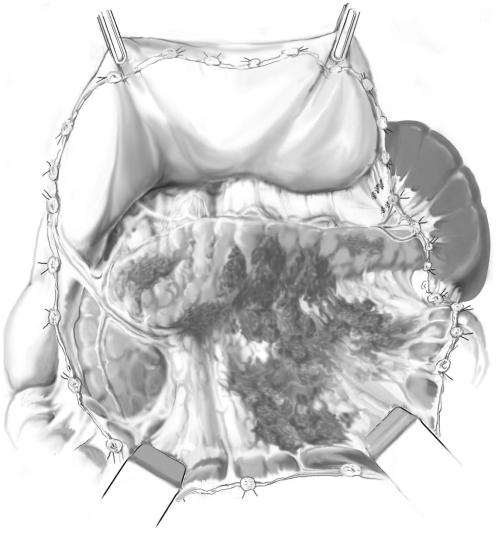

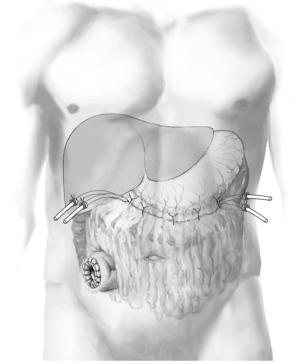

STEP 1 (continued) |

Exposure |

|

|

|

|

Caution is necessary because of inflammatory adhesions between the pancreas, transverse mesocolon, and posterior wall of the stomach.

The pancreatic area is fully exposed; necrotic areas are darker and more woodyfeeling than viable tissue.

Necrosis is usually not limited to the pancreas but also involves the peripancreatic and retroperitoneal fatty tissue as well; pancreatic parenchymal necrosis is usually patchy and superficial with deeper parts of the pancreas still perfused and viable (A-2).

A-2

Necrosectomy |

897 |

|

|

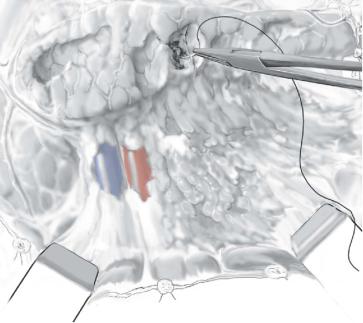

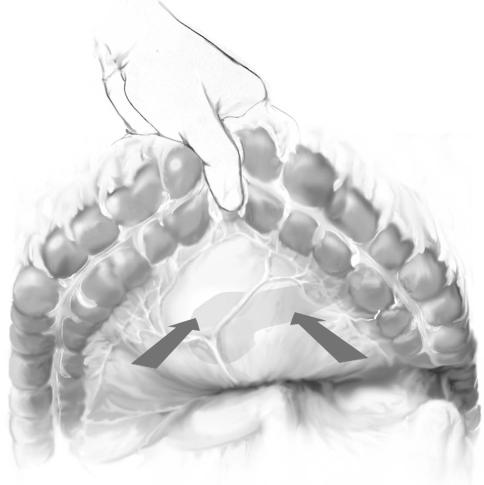

STEP 2 |

Blunt dissection of necrotic tissue |

|

All fluid collections (defined by CT images) must be opened and evacuated by suction. |

|

|

|

Removal of necrotic pancreatic and peripancreatic fatty tissue accomplished by blunt |

|

digital dissection or careful use of instruments and irrigation is the goal; sharp dissec- |

|

tion is specifically avoided specifically to prevent uncontrollable hemorrhage. |

|

Necrotic tissue is systematically sought in the retroperitoneum behind the transverse, |

|

ascending, and descending colon, and down to Gerota’s fascia; all areas of necrosis are |

|

removed by blunt dissection. |

|

Necrotic tissue and fluid from the operation room are sent for culture. |

|

After necrosectomy, the pancreatic area and the retroperitoneal cavity are irrigated |

|

generously with 4–10l of normal saline. |

898 |

SECTION 6 |

Pancreas |

|

|

|

STEP 3 |

Hemostasis after necrosectomy |

|

|

|

|

A careful blunt technique removes devitalized tissue and preserves the viable pancreatic parenchyma.

Bleeding from the pancreas is controlled by transfixion sutures using nonabsorbable, monofilament suture material.

The spleen is usually not involved specifically in the necrotic process, and thus the need for splenectomy should be very rare.

Necrosectomy |

899 |

|

|

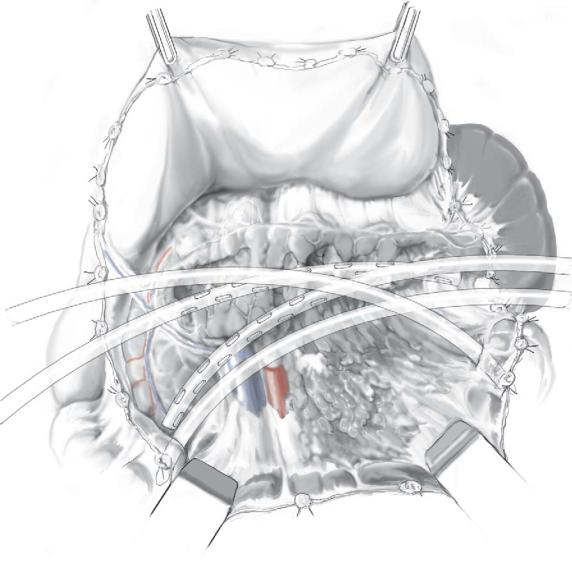

STEP 4 |

Placement of catheters for postoperative closed lavage |

|

Four drainage catheters, two from each side, are directed to the contralateral side of the |

|

|

|

peripancreatic space and placed with the tip of the catheter at the head and tail of the |

|

pancreas behind the ascending and descending colon. Two of these four catheters |

|

(sump-like tubes, 20-24Fr.) have two lumens – a smaller one for inflow of lavage fluid |

|

and a wider one for outflow; other drains (silicon tubes, 28–32Fr.) have one lumen of |

|

larger diameter to allow evacuation of both fluid and necrotic debris. |

900 |

SECTION 6 |

Pancreas |

|

|

|

STEP 5 |

Closure |

|

|

|

|

Gastrocolic and duodenocolic ligaments are re-sutured together to create a closed peripancreatic compartment to allow for contained postoperative lavage of the lesser sac and involved retroperitoneum.

With marked mesoand retrocolic necrosis threatening the viability of the transverse colon, a diverting ileostomy is created in

the right lower quadrant.

Necrosectomy |

901 |

|

|

|

Necrosectomy and Closed Packing |

|

Carlos Fernández-del Castillo |

|

|

STEP 1 |

Exposure and entry into the lesser sac, pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosectomy |

|

In any surgical approach to necrotizing pancreatitis, the goal is to remove the necrotic |

|

|

|

tissue and to minimize accumulation of exudative fluid and extravasated pancreatic |

|

exocrine secretions. Reoperation in this setting can be difficult and can lead to increased |

|

morbidity. The principle of necrosectomy and “closed packing” is to perform a single |

|

operation, with thorough debridement and removal of necrotic and infected tissue, |

|

while minimizing the need for reoperation or subsequent pancreatic drainage. |

|

For most patients, a midline incision allows better exposure and optimal placement |

|

of drains. |

|

The transverse colon is elevated anteriorly and access to the lesser sac is gained via |

|

the left mesocolon. When necrosis is extensive, often there is bulging of the necrotic |

|

process at this site and entry should be made bluntly with a clamp or finger. Fluid is |

|

evacuated and sent for culture. |

|

The opening is enlarged, and with two fingers the cavity is explored. Depending on |

|

the extent and location of necrosis, an incision can also be made in the right mesocolon |

|

and, if necessary, the middle colic vessels are clamped and ligated. |

902 |

SECTION 6 |

Pancreas |

|

|

|

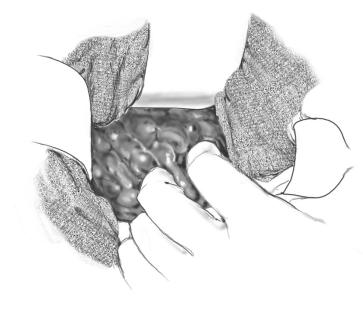

STEP 2 |

Pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosectomy/debridement |

|

|

|

|

Debridement and removal of the necrotic tissue (necrosectomy) is done bluntly with the fingers or with a sponge. It is important to break into all the recesses of the cavity as guided by the CT to thoroughly remove the debris and necrotic material, a sample of which should also be sent to bacteriology. Any firm attachments should be clamped and tied or left alone.

The pancreas can be discerned from peripancreatic tissues often only on the basis of its location and consistency. Resection of the pancreas should be done carefully and only if the CT shows pancreatic parenchymal necrosis.

If necrosis extends deep into the perirenal spaces and this cannot be accessed through the mesocolon, the respective paracolic gutters are opened to remove the debris/necrosis.

After completing the necrosectomy/debridement, the pancreatic bed is irrigated with several liters of normal saline.