clavien_atlas_of_upper_gastrointestinal_and_hepato-pancreato-biliary_surgery2007-10-01_3540200045_springer

.pdf

622 |

SECTION 4 |

Biliary Tract and Gallbladder |

|

|

|

|

Tricks of the Senior Surgeon |

|

■Preoperative stenting (endoprosthesis through ERCP by the gastroenterologist or PTC by the radiologist) may help perioperative localization of the hepatic duct in case of proximal biliary obstruction.

■If PTC is in place, it is wise to make the skin incision away from the drain. This enables the surgeon to keep the drain for later cholangiography. In an end-to-side choledochojejunostomy, the hole in the jejunum should be very small because it always ends up larger than anticipated. Collection of bile during the procedure enables the surgeon to treat the patient with a targeted antibiotic therapy in case of infectious complications.

Choledochoduodenostomy

Ted Pappas, Miranda Voss

Introduction

This procedure was first performed by Riedel in 1888 for an impacted common bile duct stone. The main principle of the procedure is that a side-to-side anastomosis is designed to allow free flow of bile from the common bile duct into the duodenum.

Advantages Over Choledochojejunostomy

|

■ |

It provides a more physiologic conduit |

|

■ |

Relatively quick and simple with fewer anastomotic sites |

|

■ |

Ease of access for future endoscopic interventions |

|

Indications and Contraindications |

|

|

Biliary dilatation resulting from: |

|

Indications |

||

|

■ |

Benign distal biliary strictures not suitable for transduodenal sphincteroplasty |

|

■ |

Indeterminate biliary stricture in the head of the pancreas where a preoperative |

|

|

decision has been made not to resect if malignancy cannot be confirmed on |

|

|

exploration and open biopsy |

|

■ |

Unresectable malignant stricture where the duodenum comfortably reaches the |

|

|

dilated biliary tree |

|

■ |

Primary or recurrent common duct stones where endoscopic management has |

|

|

failed or is not available |

|

■ |

Impacted common duct stone |

|

|

Narrow common bile duct (<8mm) |

Contraindications |

■ |

|

|

■ |

Active duodenal ulceration |

|

■ |

Malignancy when the duodenum does not comfortably reach the dilated bile duct |

624 |

SECTION 4 |

Biliary Tract and Gallbladder |

|

|

|

|

Preoperative Investigation and Preparation |

|

|

Clinical: |

Associated symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction |

|

|

History of duodenal ulceration |

|

|

Coagulopathy or biliary sepsis |

|

|

Evidence of dehydration |

|

Laboratory: |

Bilirubin |

|

|

Coagulation parameters |

|

|

Creatinine, electrolytes |

|

Radiology: |

Ultrasound to confirm site of obstruction and diameter of common |

|

|

bile duct (minimal investigation). Other investigations determined |

|

|

by underlying pathology |

|

Preparation: |

Adequate hydration |

|

|

Antibiotic prophylaxis |

What We Should Not Do

Preoperative biliary stenting may decompress the common bile duct, which will make the anastomosis more difficult. It also increases the risk of wound infection. If the time to surgery is compatible with the patient’s symptoms and cholangitis is not present, stenting should be avoided.

Choledochoduodenostomy |

625 |

|

|

Procedure

Access

Right subcostal incision or midline (see Sect.1, chapters “Positioning and Accesses” and “Retractors and Principles of Exposure”).

STEP 1

Exposure and exploration: installation of retractor (Bookwalter). The colon is reflected inferiorly.

Kocherization of the duodenum as shown in the chapter “Resection of Gallbladder Cancer, Including Surgical Staging” . Kocherization allows mobility of the duodenum that is essential for this procedure.

Cholecystectomy as shown in the chapter “Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy, Open Cholecystectomy and Cholecystostomy.”

626 |

SECTION 4 |

Biliary Tract and Gallbladder |

|

|

|

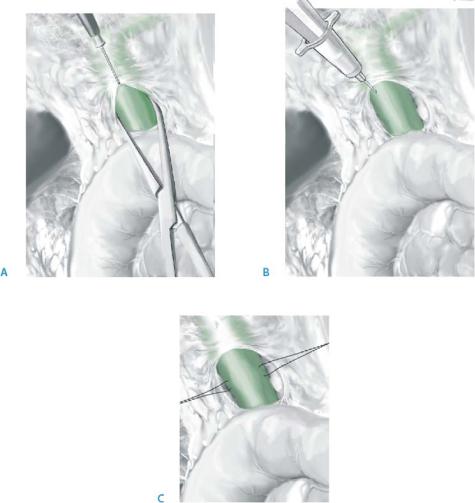

STEP 2 |

Definition of common bile duct |

|

|

|

|

Incision of hepatoduodenal ligament to expose the common bile duct (A). Site of common bile duct confirmed with “seeker needle (B).”

3-0 silk stay-sutures are placed in the common bile duct (C).

Choledochoduodenostomy |

627 |

|

|

STEP 3 |

Opening of bile duct and duodenum |

|

A 2-cm choledochotomy is performed. The distal extent of the choledochotomy should |

|

|

|

be in close proximity to the superior border of the mobilized duodenum, so that the |

|

duodenum comfortably reaches the choledochotomy. |

|

A longitudinal duodenotomy is then performed. The duodenotomy should be |

|

approximately 70% of the length of the choledochotomy. |

628 |

SECTION 4 |

Biliary Tract and Gallbladder |

|

|

|

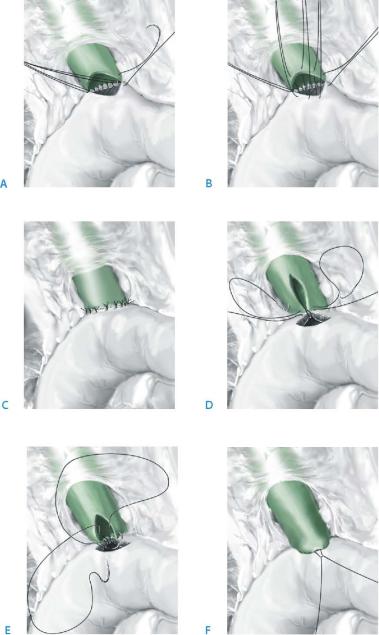

STEP 4 |

Posterior wall anastomosis |

|

|

|

|

The anastomosis is performed using interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures with knots in the lumen for the posterior wall. It is a mistake to place too many sutures; 12 are usually sufficient and the anastomosis may be visualized as a clockface.

The first suture should be placed in the 6 o’clock position (A). Traction on this suture aids in exposure for subsequent posterior wall sutures.

A further three sutures are placed out to the 3 o’clock position and three to the 9 o’clock position. All sutures are placed before tying (B).

The silk stay-sutures are removed. The anastomotic sutures are tied and all but the corner sutures are cut (C).

Choledochoduodenostomy |

629 |

|

|

STEP 5 |

Anterior wall anastomosis |

|

Traction on the corner sutures ensures that the corner is inverted. The corner may then |

|

|

|

be cut. |

|

Sutures are placed from outside to in (A). |

|

All are placed before tying (B). |

|

The enterotomy should be shorter than the choledochotomy as the small intestine |

|

always stretches during creation of the anastomosis. This can cause a size mismatch (C). |

|

Do not stent the anastomosis. |

|

[Editor’s variation: An even more facile method of completing this anastomosis is to |

|

place two absorbable sutures (3-0 vinyl) at the 6 o’clock position (D). The two sutures |

|

are then sewn in a running manner from 6 o’clock to 12 o’clock (E) and tied (F).] |

630 SECTION 4 Biliary Tract and Gallbladder

Postoperative Tests

■ Bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase

Local Postoperative Complications

■Short term:

–Wound infection; increased incidence where the bile duct has been stented.

–Bile leakage: excessive drainage fluid with high bilirubin content; rare and usually indicates a technical problem. Priorities are to establish controlled fistula and to determine whether there is unobstructed biliary enteric continuity. CT scan and fistulogram via drain are initial investigations. Most will heal spontaneously if there is no downstream obstruction.

■Medium-long term:

–Recurrent cholangitis; pain, jaundice and right upper quadrant pain with evidence of sepsis. These are most commonly the result of anastomotic stricture, but may also result from sump syndrome, development of hepatoor choledocholithiasis or disease in the upstream biliary tree. A CT scan will define the site of obstruction. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is necessary to define the anatomy of the biliary tree and for endoscopic treatment of several of the causes.

–Anastomotic stricture. The usual presentation is with cholangitis, but it may present with progressive jaundice. More likely if choledochotomy <2cm. It may respond to endoscopic balloon dilatation, but otherwise requires conversion to Roux-en-Y.

–Sump syndrome: presents with pain, cholangitis, jaundice, less commonly pancreatitis months to years postoperatively. Diagnosis is made at ERCP where the blind end of the common duct is found to be full of food debris or calculi. Initial treatment is endoscopic.

–Cholangiocarcinoma: usually occurs in patients with a long history of repeated episodes of cholangitis 10–20years postoperatively. Early symptoms are nonspecific with pain, weight loss and cholestasis. Cholangitis is unusual. Work-up of suspected cholangiocarcinoma is detailed elsewhere.

Tricks of the Senior Surgeon

■Anticipate a 50% stenosis and make the choledochotomy at least 2cm long.

■Position the choledochotomy and the enterotomy to minimize tension.

■Generous kocherization should be performed to ensure there is no undue tension on the anastomosis.

Reconstruction of Bile Duct Injuries

Steven M. Strasberg

Introduction

Bile duct injuries have become more common since the introduction of laparoscopic surgery and are a major source of morbidity and litigation. Bile duct injuries may take many forms. Simpler injuries such as types A and D may be treated in the community setting when discovered intraoperatively or by endoscopic or percutaneous techniques when they present in the postoperative period. Some more complex injuries such as E1 and E2 types may also be treated by nonsurgical techniques when they present as strictures. This chapter deals with the more complex injuries that require hepaticojejunostomy for repair (types B and C injuries and most to type E injuries).

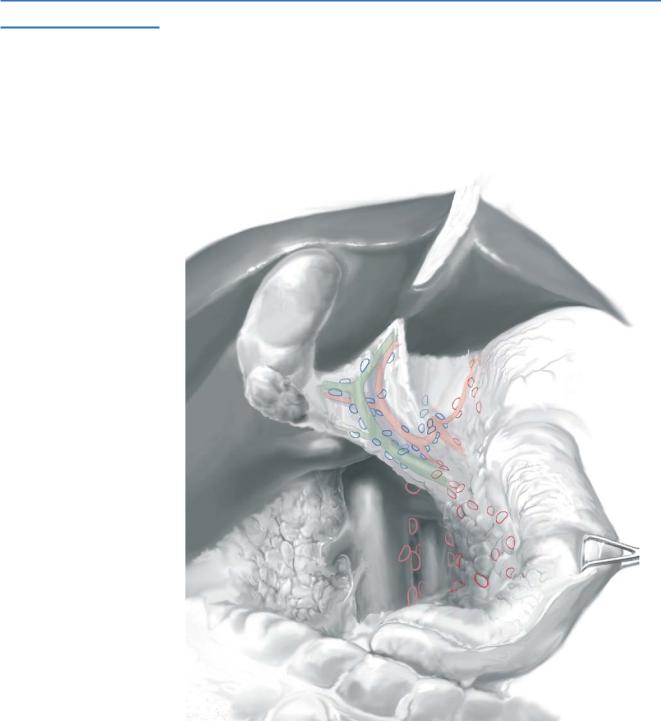

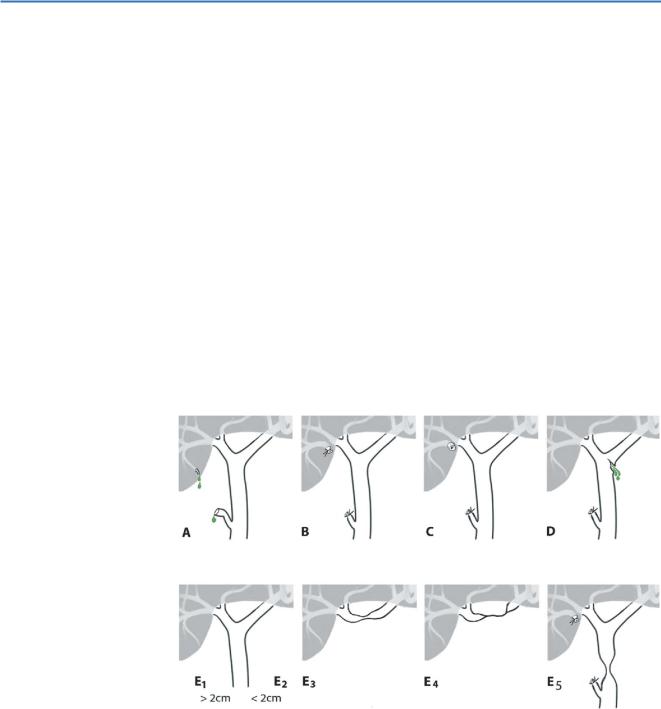

The figure illustrates the classification of injuries to the biliary tract. Type E injuries are subdivided according to the Bismuth classification. Types B and C injuries almost always involve aberrant right hepatic ducts. The notations >2 cm and <2 cm in types E1 and E2 injuries indicate the length of common hepatic duct remaining.

The injuries with an isolated right duct component and the subject of this paper are types B, C, E4 and E5.