clavien_atlas_of_upper_gastrointestinal_and_hepato-pancreato-biliary_surgery2007-10-01_3540200045_springer

.pdf

Special Maneuvers in Liver Trauma |

447 |

|

|

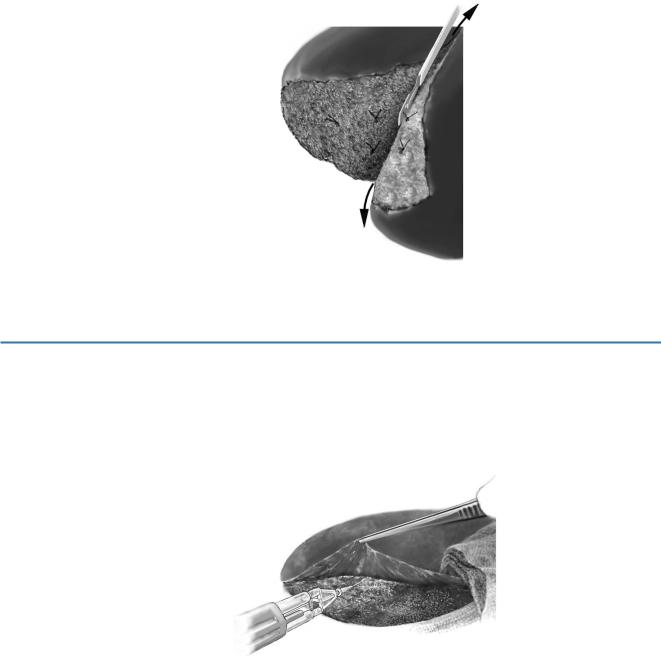

STEP 6 |

Resectional débridement |

|

Devitalized hepatic tissue needs to be removed because of the risk of abscess. |

|

|

|

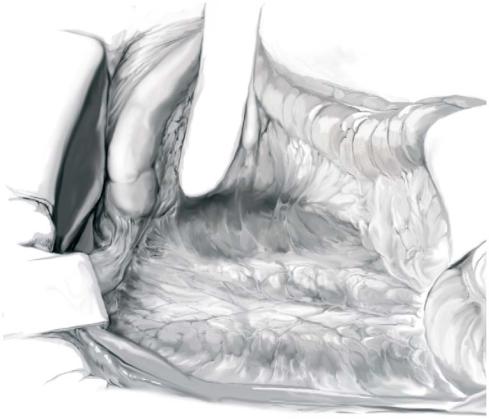

The hepatic parenchyma is divided along the line of fracture in the plane between |

|

devascularized liver and the remaining parenchyma using the back of the scalpel |

|

handle. When resistance is encountered, this indicates the elastic tissue of vessels or |

|

biliary ducts, which are doubly clamped, divided and suture ligated. In most instances, |

|

a non-anatomical resection rather than a standard anatomical hepatectomy is preferred. |

|

A major hepatectomy is rarely indicated in the presence of extended injuries. |

STEP 7 |

Ruptured subcapsular hematoma |

|

In case of a ruptured subcapsular hematoma, hemostasis is performed using an argon |

|

|

|

beam coagulator and the capsula is glued onto the bleeding parenchyma. The glue can |

|

be injected between the parenchyma and the glissonian capsule. Alternatively, the |

|

dissecting sealer (Tissue Link) can be used. |

448 |

SECTION 3 |

Liver |

|

|

|

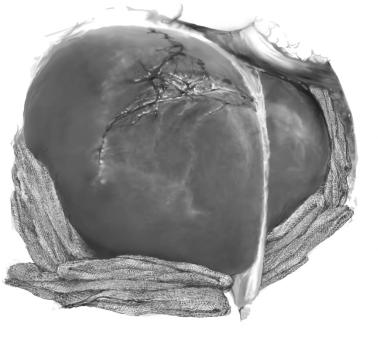

STEP 8 |

Methylene blue test and cholangiography |

|

|

|

|

After complete hemostasis, the integrity of the biliary tract is evaluated by a methylene blue test. The test can be performed through a gallbladder puncture combined with a manual choledochal compression. Biliary leaks are repaired by selective ligations.

The opening of the gallbladder wall must be closed carefully (cholecytorrhaphy). In case of limited liver trauma, a cholecystectomy is referred, allowing cholangiography through the cystic duct to detect biliary leaks into the fracture line.

Special Maneuvers in Liver Trauma |

449 |

|

|

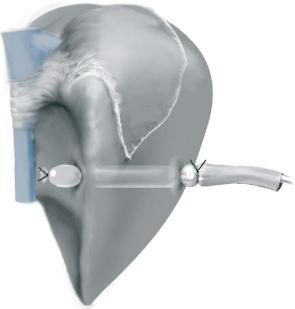

STEP 9 |

Packing |

|

Packing is the mainstay of damage control. The principle is to perform a compression of |

|

|

|

the liver against the diaphragm (upper and posterior direction), which works very well |

|

for venous bleeding. Gauze swabs are placed around the liver – not inside the lesion – |

|

in order to compress the fracture and keep the compression against the diaphragm. |

|

However, no pack should be placed between the liver and the diaphragm to avoid a |

|

compression of portal veins and vena cava compromising venous return and resulting |

|

in decreased cardiac inflow and a portal venous thrombosis. However, the elevation of |

|

the diaphragm leads to a high peak airway pressure with hypoventilation which needs |

|

to be taken into account in the postoperative care. |

|

The abdomen is closed under tension without drainage to maintain pressure on the |

|

packs. The increased intra-abdominal pressure represents a major risk for an abdominal |

|

compartment syndrome and therefore needs to be checked regularly. |

|

If the hemorrhage is not controlled, manual compression is performed again and the |

|

liver is packed one more time. If this does not lead to control of the bleeding, partial or |

|

total vascular exclusion of the liver needs to be performed (Step 10). |

450 |

SECTION 3 |

Liver |

|

|

|

STEP 10 |

Vascular control |

|

|

If packing fails to control hemorrhage in complex liver injuries, the Pringle maneuver |

|

|

||

|

allows hemorrhage control from the hepatic artery and portal venous system. The tech- |

|

|

nique also helps to rule out other sources of bleeding such as retrohepatic veins and the |

|

|

vena cava. If this does not lead to control of the bleeding (grade VI lesions), total |

|

|

vascular exclusion of the liver is performed by clamping the supradiaphragmatic IVC |

|

|

after sternotomy and the infradiaphragmatic IVC (see chapter “Techniques of Vascular |

|

|

Exclusion and Caval Resection”). The appropriate and early use of vascular control |

|

|

allows for accurate identification of the injury and the control of hemorrhage. |

|

|

|

|

STEP 11 |

Hepatic venous exclusion |

|

|

In case of a retrohepatic caval injury, an atrial-caval shunt to the superior vena cava or |

|

|

||

|

a hepatic venovenous bypass should be employed additionally to the Pringle maneuver |

|

|

early in the operation to preserve venous return while repairing the retrohepatic caval |

|

|

injury. An atrial-caval shunt can be performed with a large chest tube through the right |

|

|

atrial appendage placed and advanced into the IVC distal to the renal veins. Additional |

|

|

side holes are cut in the tube at the atrial level. Tourniquets are tightened around the |

|

vena cava at the level of the supradiaphragmatic and suprarenal cava levels and the atrial appendage.

Special Maneuvers in Liver Trauma |

451 |

|

|

STEP 12 |

Intrahepatic balloon tamponade |

|

Hemorrhage control for through-and-through penetrating liver injuries can be |

|

|

|

achieved by an intrahepatic balloon, avoiding an extensive hepatotomy (tractotomy). |

|

The intrahepatic balloon is created from a Penrose drain that acts as a balloon and |

|

hollow catheter. Inflation of the balloon causes a tamponade within the liver |

|

parenchyma. Alternatively a simple Foley catheter can be taken. The tamponade is |

|

maintained for 48h. |

452 |

SECTION 3 |

Liver |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Postoperative Management |

|

|

|

■ |

Postoperative care on the intensive care unit requires a correction of hypovolemia |

|

|

|

and the “triad of death”: hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy. |

|

|

■ |

Frequent intra-adominal pressure measurements by means of a Foley catheter in the |

|

|

|

bladder should be made after primary closure of the abdomen to detect the develop- |

|

|

|

ment of an abdominal compartment syndrome. |

|

|

■ |

If packing is decided upon, a planned reintervention (second look) with removal of |

|

|

|

the packs, as well as repacking, definitive hemostasis and definitive abdominal |

|

|

|

closure or abdominal vacuum assisted closure, is necessary after the resuscitation |

|

|

|

period. The time point of the second look depends on rewarming, correction of |

|

|

|

acidosis and coagulopathy, which usually takes 24–48h. |

|

Postoperative Complications

■Short term:

–Hemorrhage

–Abdominal compartment syndrome

–Bile leaks

–Liver failure

–Acidosis, coagulopathy and hypothermia with multiple organ failure

■Long term:

–Biloma

–Biliary fistula

–Biliary stricture

–Abscess and hematoma infection

Tricks of the Senior Surgeon

■Do not hesitate to call for help (HPB surgeon).

■Request experienced anesthesiologists.

■Ask regularly for temperature and quantity of transfusions.

■Do not mobilize the liver until volume replacement has been achieved.

■Alert the anesthesiologist prior to clamping of major vessels, as a sudden decrease in venous return is tolerated poorly by hypovolemic patients.

■A decision to use packing is usually the best in a complex situation.

Technique of Multi-Organ Procurement

(Liver, Pancreas, and Intestine)

Jan Lerut, Michel Mourad

Introduction

The growing success of liver transplantation led to the development of a flexible procedure for multiple cadaveric organ procurement as introduced by Starzl in 1984. The subsequent development of pancreas, multivisceral and intestinal transplantation has required modification and improvement of the initially described technique.

Different procedures, varying from isolated procurement of the different abdominal organs to total abdominal evisceration, were described during the 1990s.

The aim of every multiple organ cadaveric procurement should be the maximal use of organs, the minimal dissection of their cardinal structures as well as an adequate repartition of their vascular axes.

A technique combining minimal in situ dissection, rapidity, safe repartition of organs and easy acquisition of technical skills should become standard in today’s organ transplantation practice.

454 |

SECTION 3 |

Liver |

|

|

|

|

Procedures |

|

|

En Bloc Pancreas-Liver Procurement |

|

|

|

|

STEP 1 |

Access to the abdominal vessels |

|

|

A midline xyphopubic incision is performed. After exploration of the abdominal organs |

|

|

||

|

for previously undiagnosed pathologies, the white line of Toldt is incised, the right |

|

|

colon is mobilized to the left, duodenum and bowel are extensively kocherized, and the |

|

|

peritoneal root of the mesentery is divided from the right iliac fossa to the ligament of |

|

|

Treitz. |

|

Technique of Multi-Organ Procurement (Liver, Pancreas, and Intestine) |

455 |

|

|

|

|

STEP 2 |

Preparation of the major abdominal vessels |

|

|

|

|

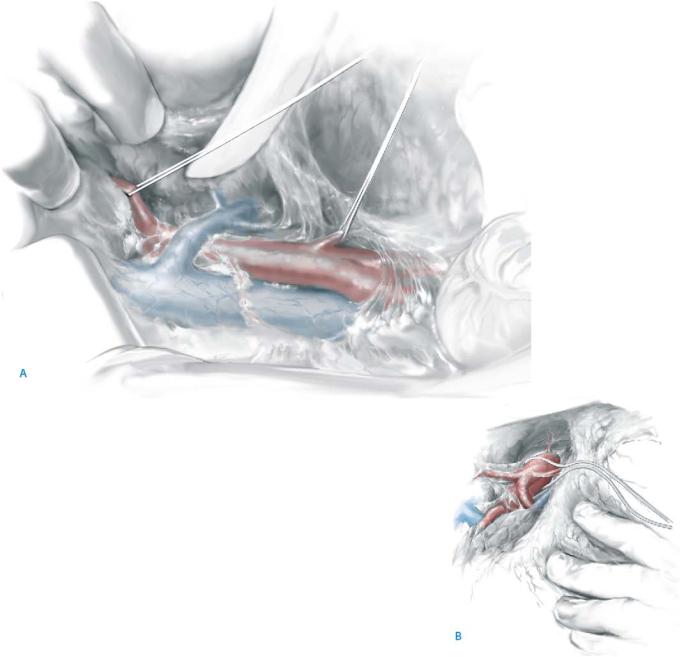

The distal abdominal aorta and the inferior vena cava (IVC) are freed from their bifurcation to the level of the left renal vein. Slight traction on the distal duodenum by the assistant allows the procurement surgeon to identify the superior mesenteric artery, located just above the left renal vein. The periarterial solar plexus is incised longitudinally on its left side in order to visualize the first 2–3cm of the superior mesenteric artery. This maneuver allows aberrant liver vascularization to be individualized

(e.g., a right hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery) (A). Next, the hepatoduodenal and hepatogastric ligaments are inspected for anatomic

variants (e.g., a left hepatic artery originating from the left gastric artery).

The supraceliac part of the aorta is prepared for later occlusion by encircling it at the supraor infradiaphragmatic level by means of a vessel loop (B).

456 |

SECTION 3 |

Liver |

|

|

|

STEP 3 |

Access to the pancreas |

|

|

|

|

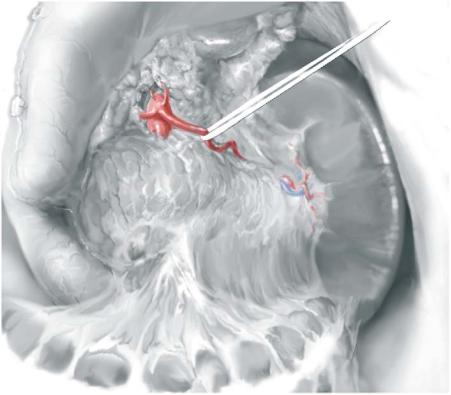

The stomach is gently separated from the transverse colon by dividing the gastrocolic ligament. This allows the whole pancreas to be visualized. The splenic artery can be encircled and marked close to its origin from the celiac trunk; this mark can be helpful during later ex-situ division of the pancreas – liver bloc.