- •Contents

- •Foreword

- •How to use this book

- •Advisory boards

- •Contributing writers

- •Contributing illustrators

- •What is an insect?

- •Evolution and systematics

- •Structure and function

- •Life history and reproduction

- •Ecology

- •Distribution and biogeography

- •Behavior

- •Social insects

- •Insects and humans

- •Conservation

- •Protura

- •Species accounts

- •Collembola

- •Species accounts

- •Diplura

- •Species accounts

- •Microcoryphia

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanura

- •Species accounts

- •Ephemeroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Odonata

- •Species accounts

- •Plecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Blattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Isoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantodea

- •Species accounts

- •Grylloblattodea

- •Species accounts

- •Dermaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Orthoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mantophasmatodea

- •Phasmida

- •Species accounts

- •Embioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Zoraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Psocoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Phthiraptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hemiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Thysanoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Megaloptera

- •Species accounts

- •Raphidioptera

- •Species accounts

- •Neuroptera

- •Species accounts

- •Coleoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Strepsiptera

- •Species accounts

- •Mecoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Siphonaptera

- •Species accounts

- •Diptera

- •Species accounts

- •Trichoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Lepidoptera

- •Species accounts

- •Hymenoptera

- •Species accounts

- •For further reading

- •Organizations

- •Contributors to the first edition

- •Glossary

- •Insects family list

- •A brief geologic history of animal life

- •Index

Order: Siphonaptera |

Vol. 3: Insects |

Species accounts

Bat flea

Ischnopsyllus octactenus

FAMILY

Ischnopsyllidae

TAXONOMY

Ischnopsyllus octactenus Kolenati, 1856. Type locality not specified.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Yellowish-brown in color. Males reach 0.09 in (2.4 mm), and females grow to 0.1 in (2.5 mm). Head, thorax, abdomen, and legs are exceptionally long and slender. The front of the head has two posteriorly directed spatulate ctenidia. Pronotum has a comb of 28 pointed ctenidia. Metanotum and abdominal terga I–VI have ctenidial combs.

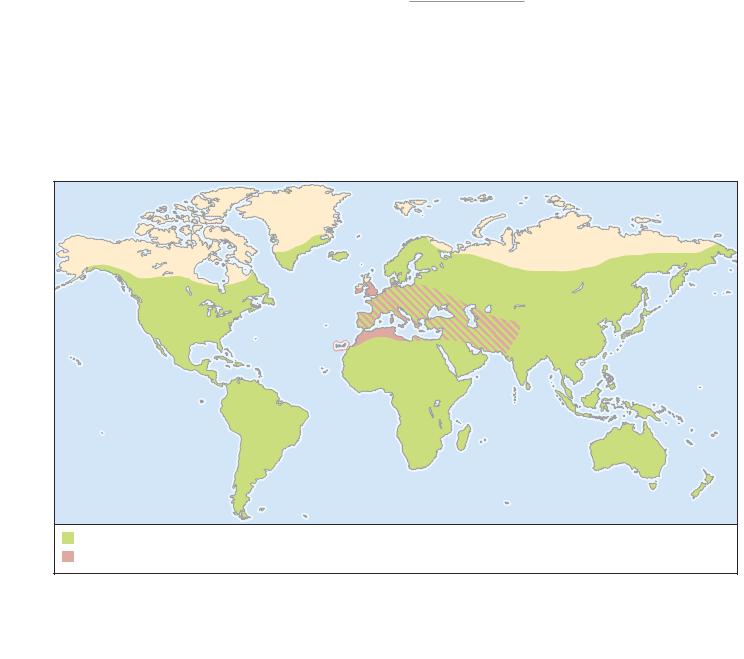

DISTRIBUTION

Europe, southern British Isles and Scandinavia, Canary Islands, North Africa and the northern Middle East to Pakistan.

HABITAT

The bat known as Kuhl’s pipistrelle (Pipistrellus kuhli) rests under the leaves and in the attics of houses, often providing close access for adult fleas.

BEHAVIOR

Bat fleas parasitize bats that roost in areas that bring them into close association with adult fleas. Immature stages develop on

the substrate below roosting bats, requiring adult fleas to climb to access the bats or to crawl up on them when baby bats fall from the ceiling and are retrieved by their mothers.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Host preferences include bats of the family Vespertilionidae, particularly Pipistrellus kuhli.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

Oriental rat flea

Xenopsylla cheopis cheopis

FAMILY

Pulicidae

TAXONOMY

Xenopsylla cheopis cheopis (Rothschild, 1903), Shendi, Sudan.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Asiatic rat flea, common rat flea, tropical rat flea, Egyptian rat flea.

Xenopsylla cheopis cheopis

Ischnopsyllus octactenus

352 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Golden brown in color. Males grow to 0.06 in (1.6 mm) and females to 0.09 in (2.4 mm). Combs are absent. Single row of setae on each abdominal tergite. Oblique row of spiniform setae on the inner aspect of hind coxa.

DISTRIBUTION

Cosmopolitan. Present wherever Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) and roof rats (Rattus rattus) are found.

HABITAT

Seaports and unsanitary situations associated with humans that provide food and harborage for rats.

BEHAVIOR

Larvae and fed adults avoid light, whereas unfed adults are attracted to light. Adults can jump 100 times their length.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Prefers commensal rodents of the genus Rattus but bites humans readily and is the most efficient vector of plague. The presence of blood and plague bacilli in the proventriculus creates a clot matrix, blocking the gut at temperatures below 80.6°F (27°C). While the proventriculus is blocked, the flea repeatedly attempts to feed, injecting the deadly plague organisms into the host (human or rat). At ambient temperatures of 80.6°F (27°C) or greater, the blockage clears by a combination of enzymes present in the plague bacillus and in the flea’s gut. For this reason urban plague epidemics caused by X. c. cheopis do not occur during warm seasons.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Males cannot mate until they have fed. Feeding triggers the dissolution of the testicular plug, allowing spermatozoa to pass during copulation. Copulation takes about 10 minutes. Eggs are 0.01–0.02 in (0.3–0.5 mm) in diameter, oval, and white, with a sticky surface. They are laid off the host. Eggs hatch in 2–21 days; three larval stages require about 9–15 days to pupation. Adults may emerge from pupae after a week or more. The life cycle can be completed at a temperature range of 64.4–95°F (18–35°C) but optimally at 80.6°F (27°C), with relative humidity above 60% (optimally 80%).

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

X. c. cheopis was responsible for the plague pandemic of Europe in the fourteenth century, which is estimated to have killed 25 million people.

Helmet flea

Stephanocircus dasyuri

FAMILY

Stephanocircidae

TAXONOMY

Stephanocircus dasyuri Skuse, 1893, New South Wales, Australia.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Dark reddish-brown color. Males reach 0.114 in (2.9 mm), and females reach 0.118 in (3.0 mm). The head is divided into a

Order: Siphonaptera

forward plate of 14 pointed ctenidia, referred to as a “helmet” or a “crown of thorns,” and a rear plate on each side of the head bearing the antenna and genal combs of seven pointed ctenidia. The pronotum has a comb of 22 pointed ctenidia. There are two rows of setae on each abdominal tergite. The dorsal margin of each hind tibia is adorned with a row of setae resembling the teeth of a comb. Three antesensilial bristles occur on each side of the seventh tergite.

DISTRIBUTION

Coastal areas of southern and eastern continental Australia and Tasmania.

HABITAT

Foothill habitats of New South Wales, Queensland, and Tasmania.

BEHAVIOR

Nothing is known.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Wide range in host preferences but found most frequently on quolls (Dasyuridae), potoroos (Macropodidae), and longand short-nosed bandicoots (Peramelidae).

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Nothing is known.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

Chigoe

Tunga penetrans

FAMILY

Tungidae

TAXONOMY

Tunga penetrans Linnaeus, 1758, America.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Jigger, chigger (not to be confused with the six-legged larval “chigger” mite belonging to the family Trombiculidae), sand flea; Spanish: Chique.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Yellow color, similar to straw. Males and females are about 0.04 in (1.0 mm) long, but gravid females may attain 0.16 in (4.0 mm). Front of head acutely pointed upward. No combs or spinelike setae. Single row of setae on each tergite. Posterior four pairs of spiracles greatly enlarged. Distinct tooth on apex of hind coxa.

DISTRIBUTION

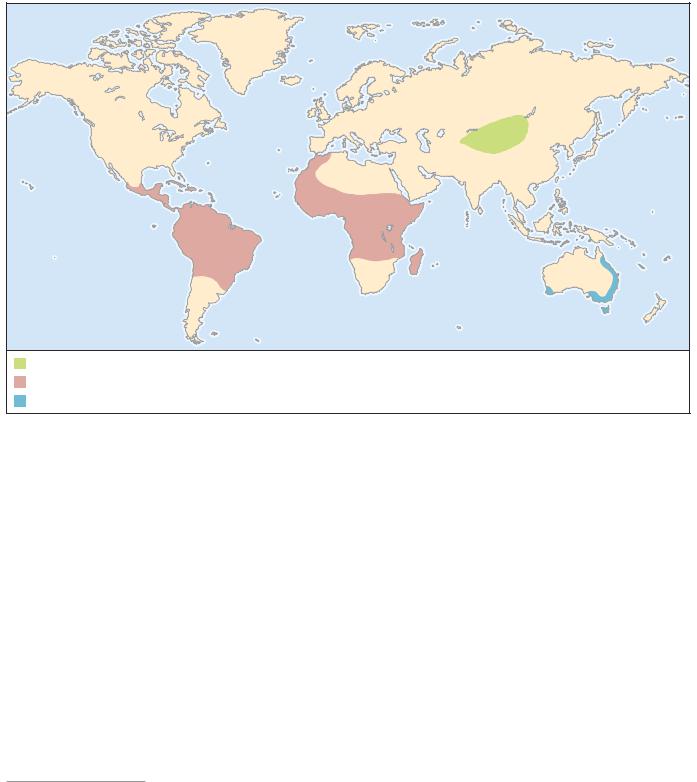

Southern United States, Central and South America, West Indies, and tropical Africa.

HABITAT

Unsanitary situations.

BEHAVIOR

Adults will pass through clothing to feed.

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

353 |

Order: Siphonaptera |

Vol. 3: Insects |

Dorcadia ioffi

Tunga penetrans

Stephanocircus dasyuri

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET |

OTHER COMMON NAMES |

Male and female fleas bite humans intermittently. They prefer the feet, but other areas of the body are not exempt. Only impregnated females permanently attach to the host. They usually select tender areas between the toes, under the nail beds, and along the soles of the feet.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

After insemination, the female seeks a host and permanently attaches, is enveloped by the swelling host tissues, and becomes replete with eggs. Eggs are released into the environment and hatch; larvae require about 10–14 days to pupation. Under optimal conditions, adults emerge after about 10–14 days.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

None known.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Distinctly intermixed pale and dark brown markings. Males grow to 0.13 in (3.3 mm), and females reach 0.18 in (4.5 mm); gravid females may attain 0.6 in (16 mm) by neosomatic growth. Combs are absent. Exceedingly long and multisegmented labial palpus.

DISTRIBUTION

Mongolia, Russia, and the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Xinjiang, Gansu, and Xizang.

HABITAT

Pastures and agricultural areas suitable for domestic sheep, cattle, goats, and wild ungulates.

Bites cause extreme irritation. Embedded females may form pustules and cause secondary infections resulting in the sloughing away of toes. Gangrene may ensue and require surgical amputation. Removal of embedded females facilitates healing.

Sheep and goat flea

Dorcadia ioffi

FAMILY

Vermipsyllidae

TAXONOMY

Dorcadia ioffi Smit, 1953, Issyk-Kul, Tien Shan, Turkestan.

BEHAVIOR

The legs of engorged females are of little use because of the enormous size of the abdomen. Such females often are seen moving through the host’s hair by wormlike contractions.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Although males feed less than females, they both imbibe blood. Males attach to the skin along the sides of the neck, and gravid females have been noted to attach to the inside of the nostrils of wild and domestic even-toed ungulates.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Winter months occur from November to March in the range of this flea. From December through February, animals may have 100–200 adult fleas. The ratio of male to female occur-

354 |

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

Vol. 3: Insects |

Order: Siphonaptera |

ring on hosts is 1:10. Eggs are expelled into the environment |

CONSERVATION STATUS |

in about March. Eggs are oval and darkly pigmented. As spring |

Not threatened. |

temperatures increase, eggs hatch. Larval development pro- |

|

gresses until pupation in August, and adults emerge in Novem- |

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS |

ber. The life cycle requires about nine months. |

Parasites of domestic animals; not known to bite humans. |

Resources

Books

Hopkins, George Henry Evans, and Miriam Rothschild. An Illustrated Catalogue of the Rothschild Collection of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the British Museum (Natural History). Vols. 1–5. London: British Museum (Natural History), 1953–1971.

Mardon, D. K. An Illustrated Catalogue of the Rothschild Collection of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the British Museum (Natural History). Vol. 6. London: British Museum (Natural History), 1981.

Rothschild, Miriam, and Robert Traub. A Revised Glossary of Terms Used in the Taxonomy and Morphology of Fleas.

London: British Museum (Natural History), 1971.

Smit, F. G. A. M. An Illustrated Catalogue of the Rothschild Collection of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the British Museum (Natural History). Vol. 7. London: British Museum (Natural History), 1987.

—. “Key to the Genera and Subgenera of Ceratophyllidae.” In The Rothschild Collection of Fleas. The Ceratophyllidae: Key to the Genera and Host Relationships, edited by Robert Traub, Miriam Rothschild and John F. Haddow. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Traub, Robert, Miriam Rothschild, and John F. Haddow. The Rothschild Collection of Fleas. The Ceratophyllidae: Key to the Genera and Host Relationships. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Periodicals

Audy, J. R., F. J. Radovsky, and P. H. Vercammen-Grandjean. “Neosomy: Radical Intrastadial Metamorphosis Associated with Arthropod Symbioses.” Journal of Medical Entomology 9 (1972): 487–494.

Cavanaugh, D. C.. “Specific Effect of Temperature upon Transmission of the Plague Bacillus by the Oriental Rat Flea, Xenopsylla cheopis.” American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 20 (1971): 264–273.

Humphries, D. A. “The Mating Behavior of the Hen Flea Ceratophyllus gallinae (Schrank) (Siphonaptera: Insecta).” Animal Behavior 15 (1967): 82–90.

Lewis, Robert E. “Résumé of the Siphonaptera (Insecta) of the World.” Journal of Medical Entomology 35 (1998): 377–389.

Lewis, Robert E., and David Grimaldi. “A Pulicid Flea in Miocene Amber from the Dominican Republic (Insecta: Siphonaptera: Pulicidae).” Novitates 3205 (1997): 1–9.

Rothschild, Miriam. “Fleas.” Scientific American 213 (1965):

44–53.

—.“Neosomy in Fleas, and the Sessile Life-Style.” Journal of the Zoological Society of London 226 (1992): 613–629.

—.“Recent Advances in Our Knowledge of the Order Siphonaptera.” Annual Review of Entomology 20 (1975): 241–259.

Whiting, M. F. “Mecoptera Is Paraphyletic: Multiple Genes and a Phylogeny for Mecoptera and Siphonaptera.”

Zoologica Scripta 31 (2002): 93–104.

Other

“Fleas (Siphonaptera): Introduction.” [May 8, 2003]. <http:// www.zin.ru/Animalia/Siphonaptera/intro.htm>.

Flea News. [May 8, 2003]. <http://www.ent.iastate.edu/ FleaNews/AboutFleaNews.html>.

Fleas of the World. Whiting Lab, Insect Genomics. [Sept. 18, 2003]. http://fleasoftheworld.byu.edu>.

Michael W. Hastriter, MS

Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia |

355 |

This page intentionally left blank